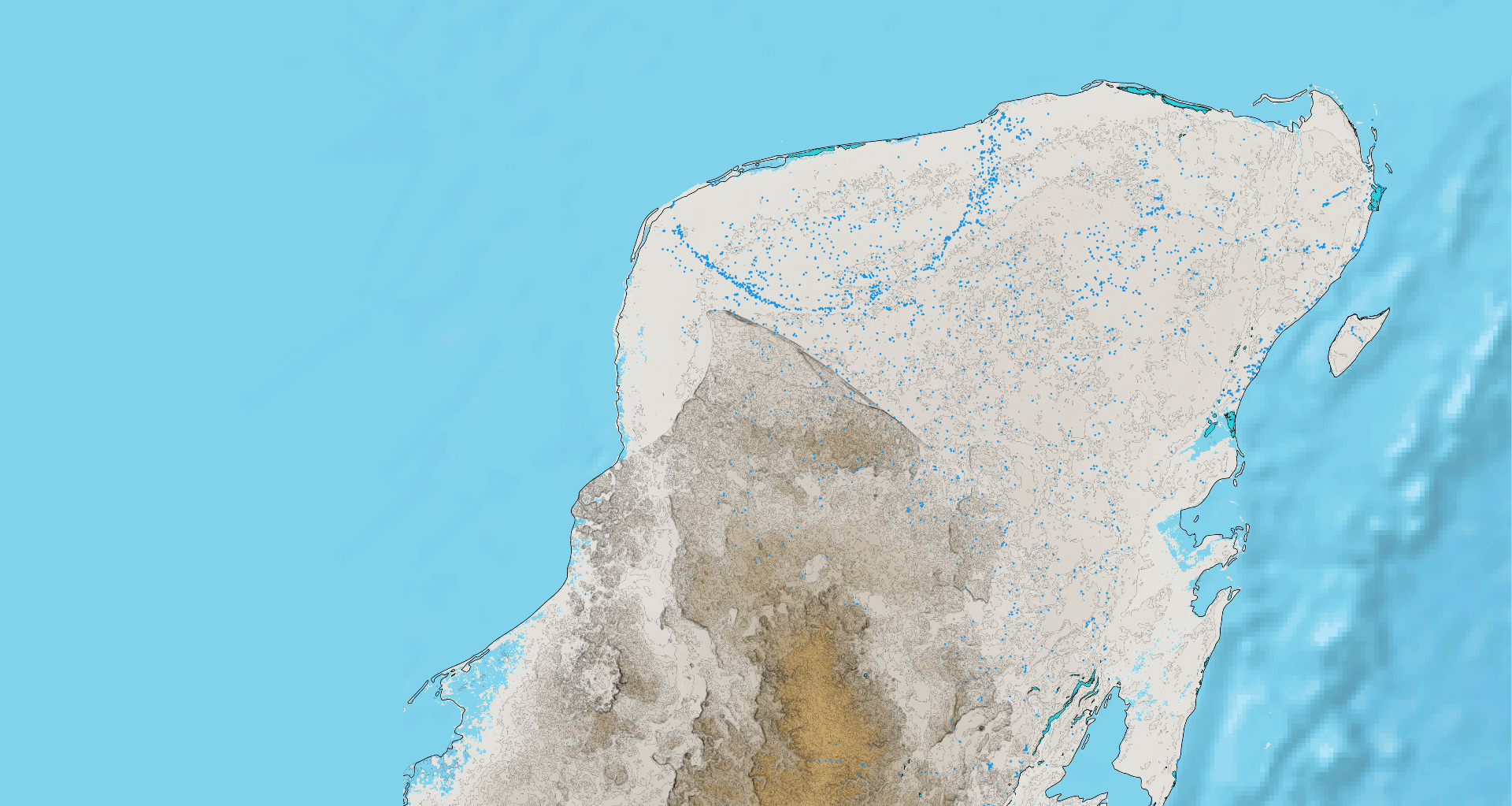

One of the distinctive features of the northern Yucatán Peninsula is its relatively flat topography, devoid of valleys or mountains, with elevations barely exceeding 30 meters. The terrain is primarily composed of limestone, or sascab (white earth), which contains calcium and magnesium carbonates that are slightly soluble in water.

In this type of rock, dissolution processes of the limestone are common, creating voids and conduits that grow over time, forming extensive underground galleries and intricate cave systems. This process is called karstification, derived from the Karst region in Slovenia, which has served as a reference for describing its characteristic landscapes. For this reason, the soil in the peninsula is often referred to as “karst,” more accurately describing a mass of rock that has undergone the geomorphological processes of karstification. In fact, this process continues to occur today.

Systematic exploration of the underwater caves in Quintana Roo began in Tulum in the mid-1980s. Various diving teams started exploring the region’s cenotes and discovered extensive passages that expanded as they connected their records.

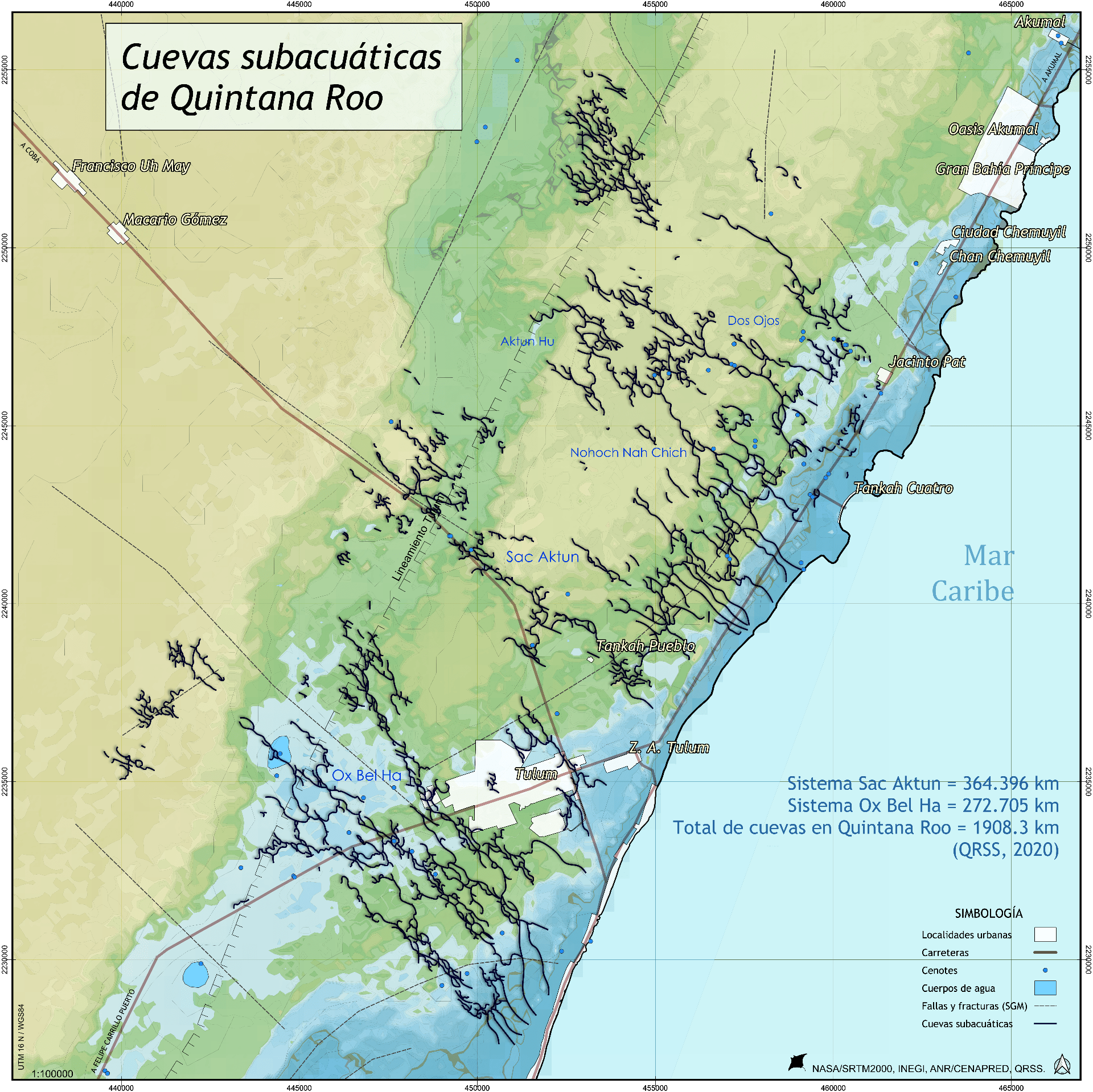

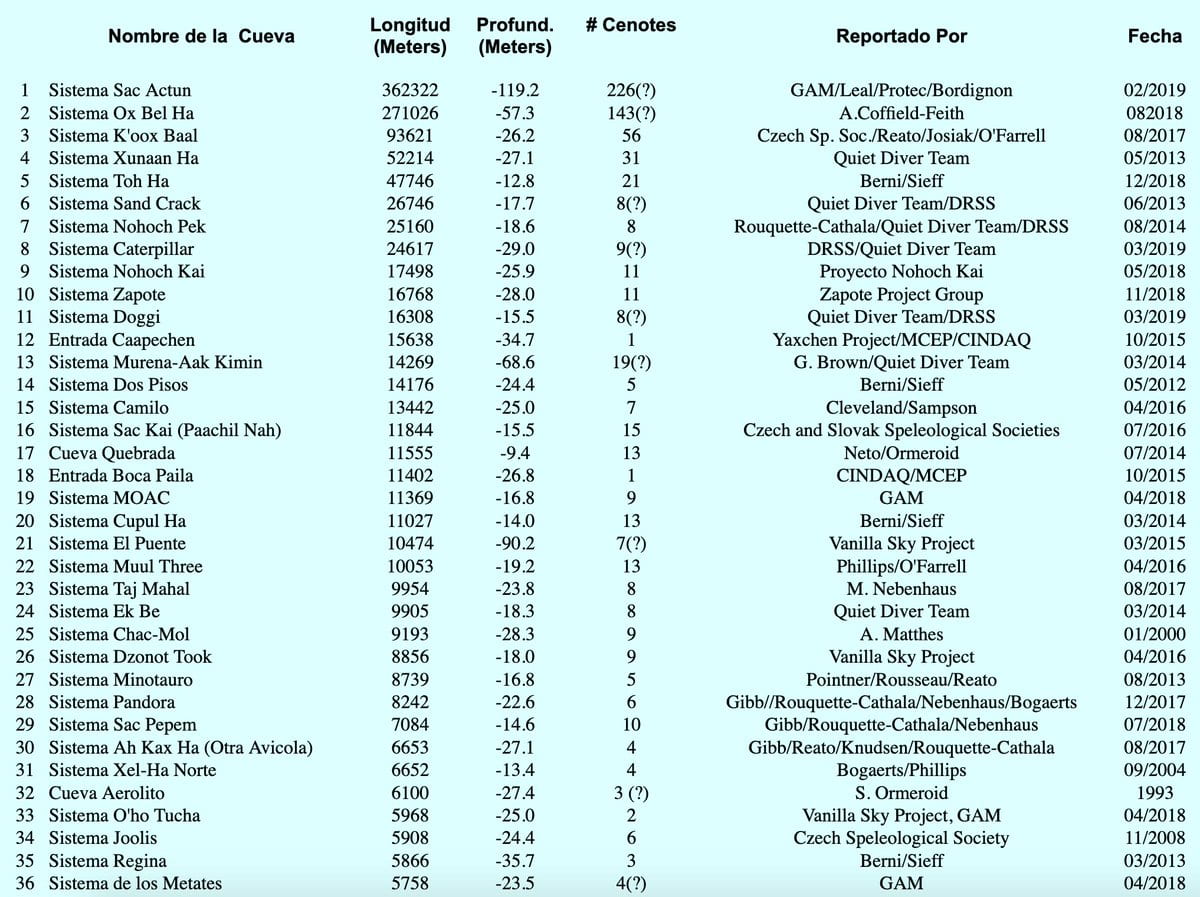

Underwater Caves of Quintana Roo

The longest underwater cave on Earth is located beneath the municipality of Tulum in Quintana Roo, Mexico. It spans over 360 kilometers at an average depth of 21 meters and a maximum depth of 120 meters in a deep cavity called “El Pit.” The Sac Aktun System, meaning “white cave,” discharges infiltrated rainwater through the rock into the Caribbean Sea via springs and inlets such as Xel Ha and Yalkú. When sea levels drop, caves previously filled with water become air-filled, losing support and causing the collapse of the roof in various sections, creating access points to the cave. The Sac Aktun System has over 220 cenotes.

Anthropological Findings

The extensive cave system beneath the Yucatán Peninsula has proven to be a guardian of invaluable anthropological and paleontological treasures for understanding history. Remains of Pleistocene animals and humans, dating back long before the Maya civilization, have been found in its underwater passages and galleries. Underwater, these caves provide a unique environment for preserving human and animal remains.

In 2006, the nearly complete (90%) skeleton of the “Woman of Las Palmas” was found in another underwater cave 4.5 km from Tulum, corresponding to a woman aged 45–50 years and 1.52 meters tall. These findings are key to understanding the peopling of our continent.

A few years earlier, in 2004, the remains of the “Woman of Naharon,” aged 20–25 years, were found at a depth of 23 meters and 370 meters from the nearest entrance in the Naranjal System. Her remains were dated to 13,600 years ago, although this date is under dispute, and further dating is ongoing.

The “Youth of Chan Hol” was found in the Chan Hol cenote of the 32-km-long Toh Ha System. The body was possibly placed in a funerary ceremony at the end of the Pleistocene, when sea levels were 120 meters lower and before the caves the youth explored were flooded. Isotope analysis of a speleothem associated with the bone suggests an age of ~13,000 years. In February 2012, various media reported the findings, and days later, the cave was vandalized, with many bones stolen between March 16–23 by unidentified individuals. For this reason, many locations are kept secret.

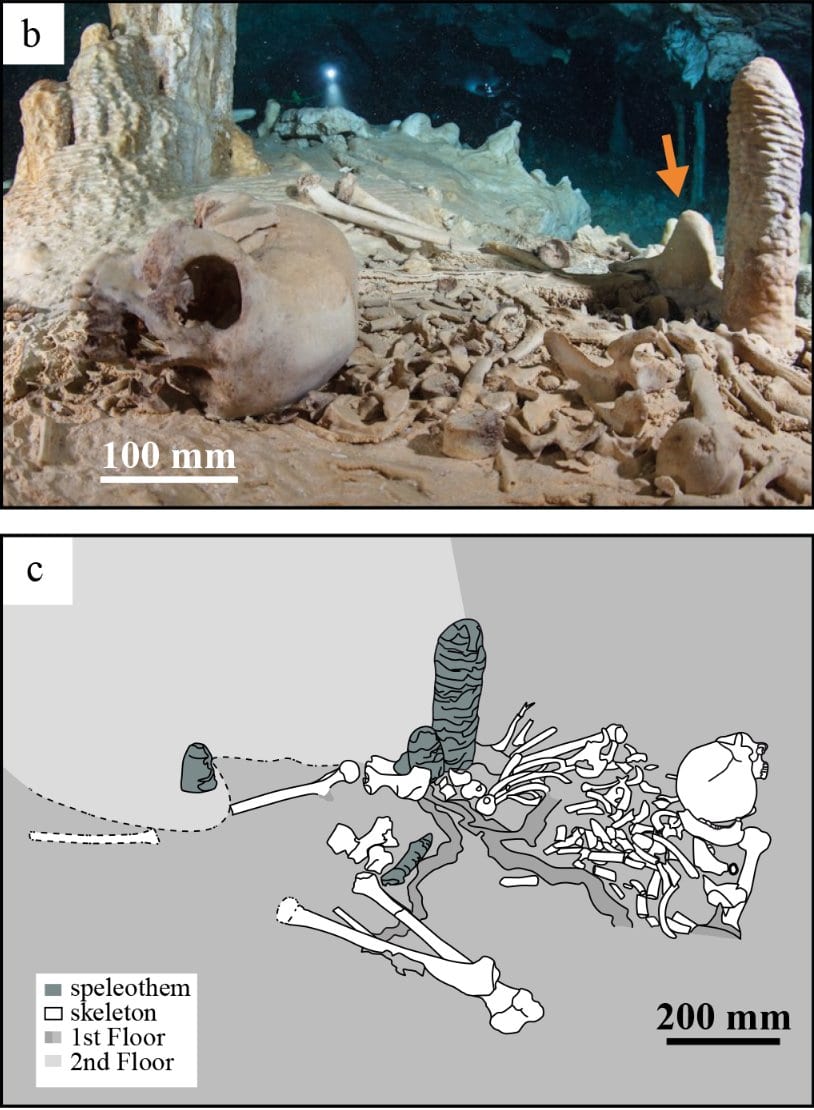

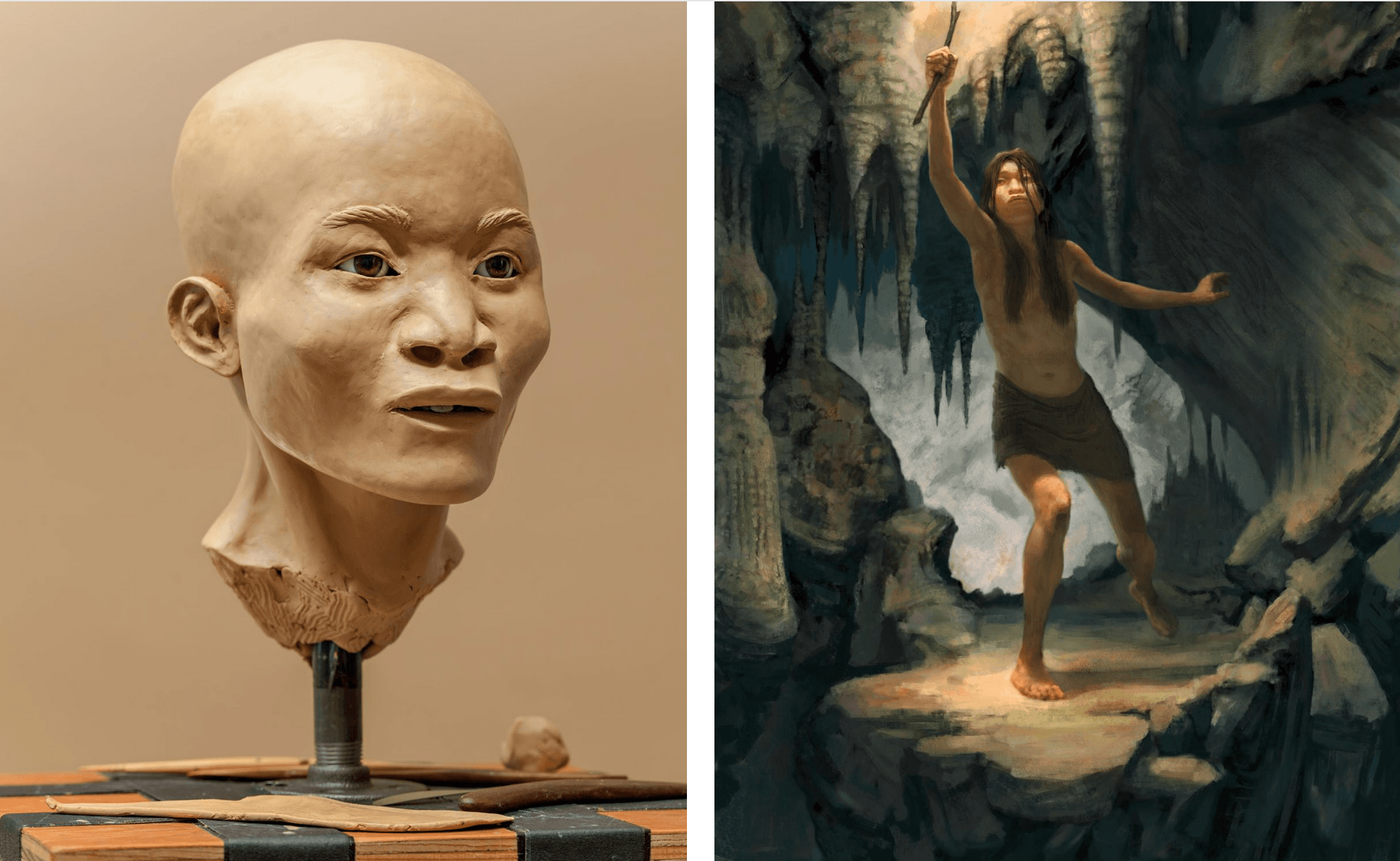

The Story of Naia

In March 2008, in the Aktun Hu section of the Sac Aktun System, in a place called “Hoyo Negro,” the remains of a woman aged 15–17 years, named Naia, were found at a depth of 42 meters, with an estimated age of 12,000–13,000 years.

Exploring divers found her in her underwater tomb, alongside remains of other animals identified as saber-toothed cats, gomphotheres (related to modern elephants), giant tapirs, boars, bears, pumas, bobcats, coyotes, coatis, and bats.

In the years following the discovery, careless divers handled the remains, and to prevent further interference, the bones were removed from the cave between 2014 and 2016, enabling further scientific studies. Mitochondrial DNA analysis of Naia has indicated a genetic link between Paleo-Americans and modern Native Americans.

Carbon-14 dating of her tooth enamel yielded a maximum age for Naia of approximately 12,900 years. Calcium carbonate accumulations that grew over Naia’s bones have been dated to 12,000 years using the uranium-thorium (U/Th) method.

The Karst-Anthropogenic System

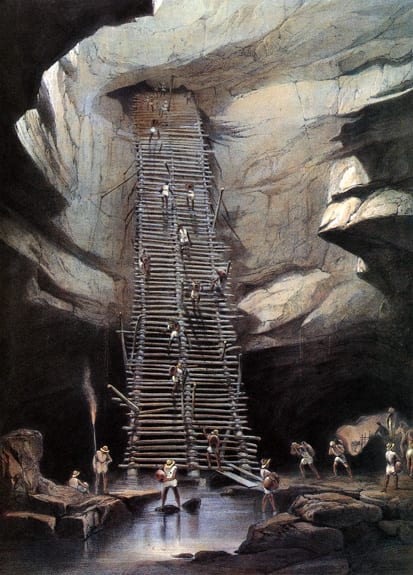

The caves and cenotes of the Yucatán Peninsula have been used as shelters and for other activities for a long time. Based on their use, they could be subdivided into sanctuaries, utility rooms, and places where water and sascab were extracted.

Caves with natural lighting were used as workspaces: pottery, grinding stones, and other stone items have been found in them. The third group of caves was used to collect clay or sascab for making pottery or as stucco for finishing house walls. It is evident that the underground cavities were partially modified or rebuilt during their use by their inhabitants.

In the 1980s, the Yucatán Peninsula, particularly Quintana Roo, experienced the beginning of a tourism development boom and a significant transformation of the karst system with a strong anthropogenic component.

Cave and cenote systems are subject to mechanical destruction by explosives or machinery, as occurs in many sites adapted for “rafting” in phreatic caves (underground rivers), which increases the infiltration of contaminants into deeper layers.

Currently, the impact on the karst landscape of the Yucatán Peninsula is considerable, also associated with tourism and intensive visits to archaeological zones, caves, and cenotes.

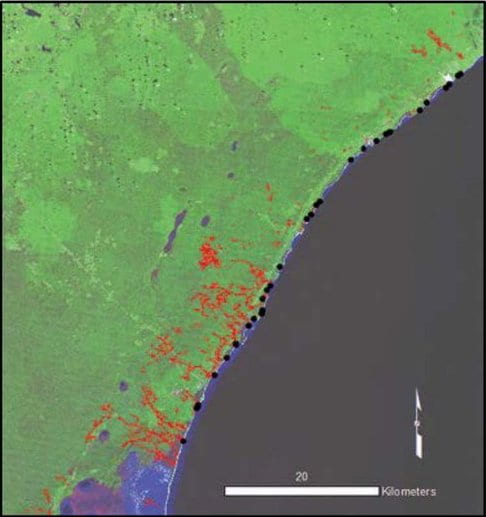

The Tren Maya, if completed, must safely address the technical challenges of crossing over the world’s largest underwater cave systems, such as the Sac Aktun and Ox Bel Ha systems. Like these, dozens of systems exist along the eastern coast of Quintana Roo.

The most comprehensive list and associated maps of Quintana Roo’s underground systems are published by the Quintana Roo Speleological Survey (QRSS).

Hydrogeological System

The Sac Aktun System is just one of many caves that discharge infiltrated rainwater from the subsurface into the Caribbean Sea, acting as natural drains. Collapses in various roof sections have formed over 220 cenotes, used for commercial and recreational purposes around the Tulum area.

The area containing Sac Aktun has a cave density of 2.9 km/km². In the Ox Bel Ha area, the cave density reaches 5.2 km/km². These cave systems maintain the hydrological balance of the region by discharging infiltrated rainwater into the Caribbean Sea.

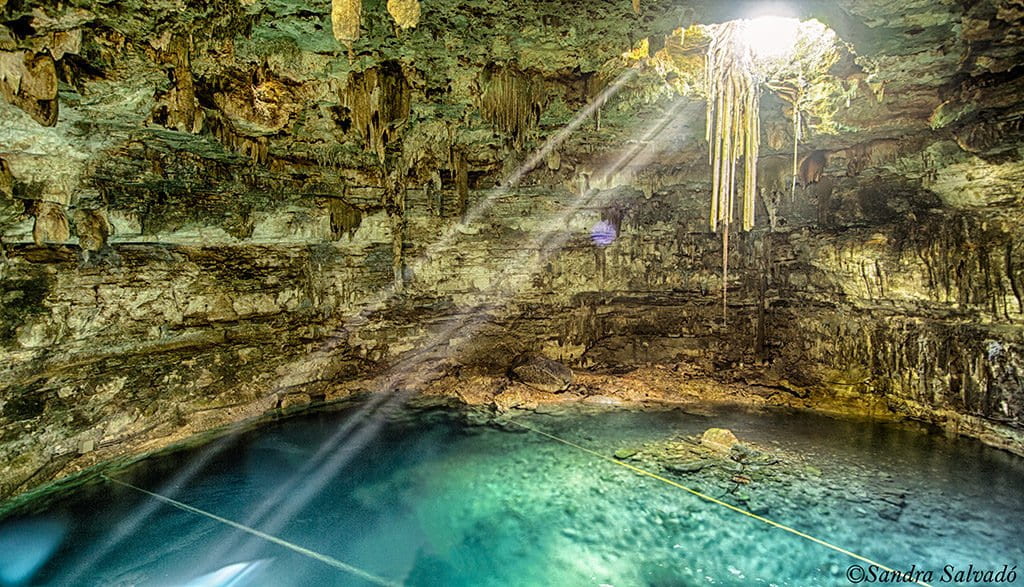

Today, the term “cenote” is used to designate any underground space with water and an opening to the outside. Cenotes form when thin sections of the roof collapse onto the cavities along the cave, creating new entrances to the underground world.

In the Samulá cenote in Valladolid, Yucatán, one can clearly observe the pile of rocks that collapsed from the roof on the floor. Recent stalactites and roots descending from the surface in search of water are also visible.

For example, in the Suytun cenote, also near Valladolid, the collapsed rocks were used to build a platform for visitors.

The collapsing roof sections can be small or very large, leading underground to wide galleries or narrow water-filled passages. Cenotes are also entry points for light and organic matter into the hydrogeological system, interacting with groundwater.

As seen, underwater cave systems discharge infiltrated water from the jungle into the Caribbean Sea. Occasionally, large sections of the cave roof near the coast collapse, forming “caletas” such as the well-known Xel Ha, Xcaret, and Yalkú, with significant groundwater flows into the ocean.

It can also happen that caves extend beyond the coastline and discharge ‘fresh’ water directly through openings in the shallow seafloor. These are called “ojos de agua” (water springs), which are very common, for example, in the Puerto Morelos reef lagoon.

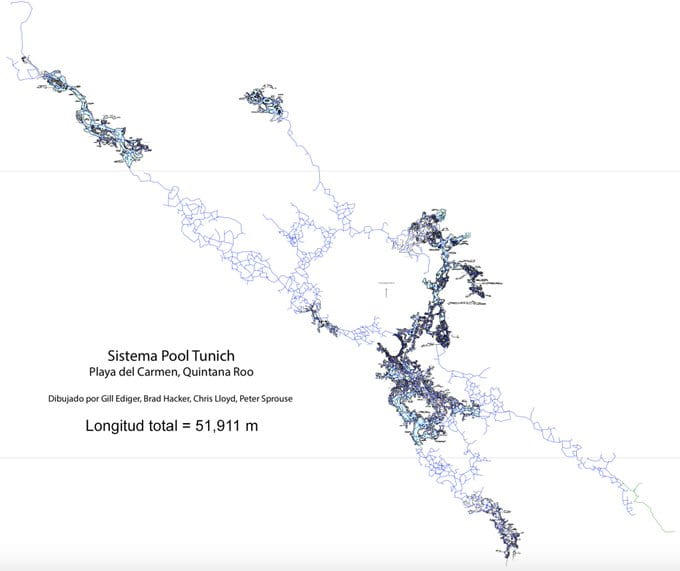

Between Akumal and Playa del Carmen, 330 km of passages in over 250 dry caves have been recorded, some just above the current sea level in the epiphreatic zone, which experiences periodic flooding. The largest is the Pool Tunich System (Río Secreto), with 51.9 kilometers in length. Within this 234 km² area, the cave density is 0.5 km/km².

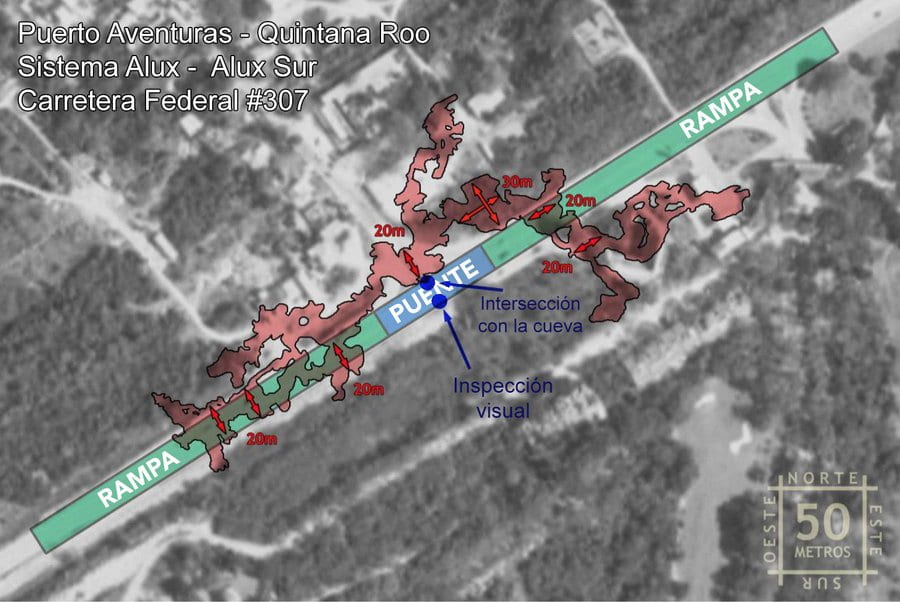

Other dry cave systems include the Sac Muul System and the Alux System, which extends beneath Federal Highway #307 near Puerto Aventuras.

Risks in the Karst

In some places, the roof thickness is less than 1.5 meters. Inside the cave, it is possible to hear cars passing overhead on the highway. Like the Alux System, there are numerous cavities along Highway #307, as it coincides with the beach ridge, the edge with the highest elevation.

Collapses occur naturally and without warning; they are difficult to predict. Their frequency may increase if controls to ensure construction safety are lacking. Risks can be minimized by considering the region’s characteristics.

The high density of caves and cenotes within Tulum’s urban area poses a direct threat to the construction of large-scale tourism and housing developments, as in many sections, the cave roof is very thin. Protecting the Sac Aktun System—and many other equally important systems in the region—from human impact requires strict regulations on wastewater treatment in the Riviera Maya, construction oversight, and continuous hydrogeological research and monitoring of the region’s karst aquifer. This must undoubtedly be included in regional development policies and considered for future tourism and transportation projects.

For sustainable use of these systems, a comprehensive understanding of cenotes, caves, groundwater movement, and their interaction with the rocks forming the aquifer, the influence of the ocean and its tides (i.e., the study of the peninsula’s complete hydrogeological system), is necessary. It is also essential to assess the impact of urban areas and potential causes of contamination of the only water source available—groundwater. This pursuit must involve the convergence of environmental sciences, water sciences, earth sciences, biological sciences, the study and conservation of the underground conduit network, knowledge accumulated in communities, efficient resource exploitation, and, of course, sustainable exploration and use through cave diving.

Direct and indirect surveys and specific topographic studies are necessary to determine the location not only of extensive cave systems but also of scattered, isolated cavities, which are abundant throughout the karst region, for any large-scale infrastructure project.

“Entering a cave is an unforgettable experience. Caves speak to us of geology, biochemistry, paleontology, and archaeology. Caves teach us history, motivate us to learn about them, and inspire us to think about their future.”

Related links

https://divemagazine.com/scuba-diving-news/divers-fear-tren-maya-train-could-destroy-cenotes

https://divemagazine.com/print-issues/tren-maya-destroying-yucatan-cenotes

Land of Cenotes

Suggested citation for this article:

Monroy-Ríos E (2019) Along the Routes of the “Tren Maya.” Karst Geochemistry and Hydrogeology – Personal Blog. Published on August 4, 2019. Accessed on: [dd/mm/yy]. https://sites.northwestern.edu/monroyrios/2025/05/09/along-the-routes-of-the-tren-maya/

References

Kambesis P & Coke JG (2016) The Sac Actun System, Quintana Roo, Mexico. Boletín Geológico y Minero127(1):177-192.

Lebedeva EV, Mikhalev DV, & Nekrasova LA (2017) Evolutionary stages of the karst-anthropogenic system of the Yucatán Peninsula. Geography and Natural Resources38(3):303-311. doi: 10.1134/S187537281703012X

QRSS (2018) List of Long Underwater Caves in Quintana Roo Mexico. Quintana Roo Speleological Survey. National Speleological Society (NSS). Consultada el 12 de julio de 2019.

Stinnesbeck W, Becker J, Hering F, Frey E, González AG, Fohlmeister J, et al. (2017) The earliest settlers of Mesoamerica date back to the late Pleistocene. PLoS ONE12(8): e0183345. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0183345

Veni, G. (1990) Maya Utilization of Karst Groundwater Resources. Environmental Geology and Water Sciences16(1):63-66. doi: 10.1007/BF01702224

Related Posts