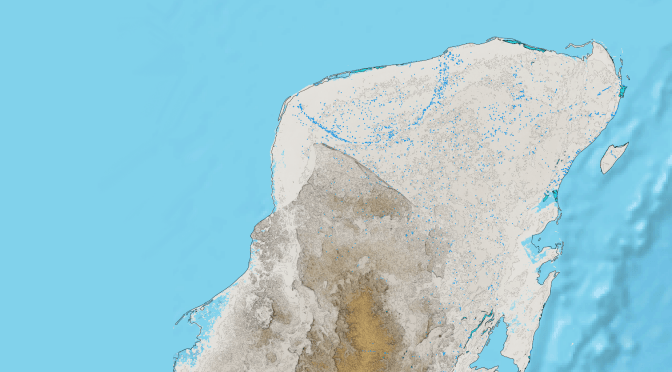

Uno de los rasgos distintivos del norte de la Península de Yucatán es su topografía relativamente plana, sin valles ni montañas y con altitudes que apenas rebasan los 30 metros. El terreno se compone principalmente de roca caliza, o sascab (tierra blanca), la cual contiene carbonatos de calcio y magnesio que son ligeramente solubles en agua.

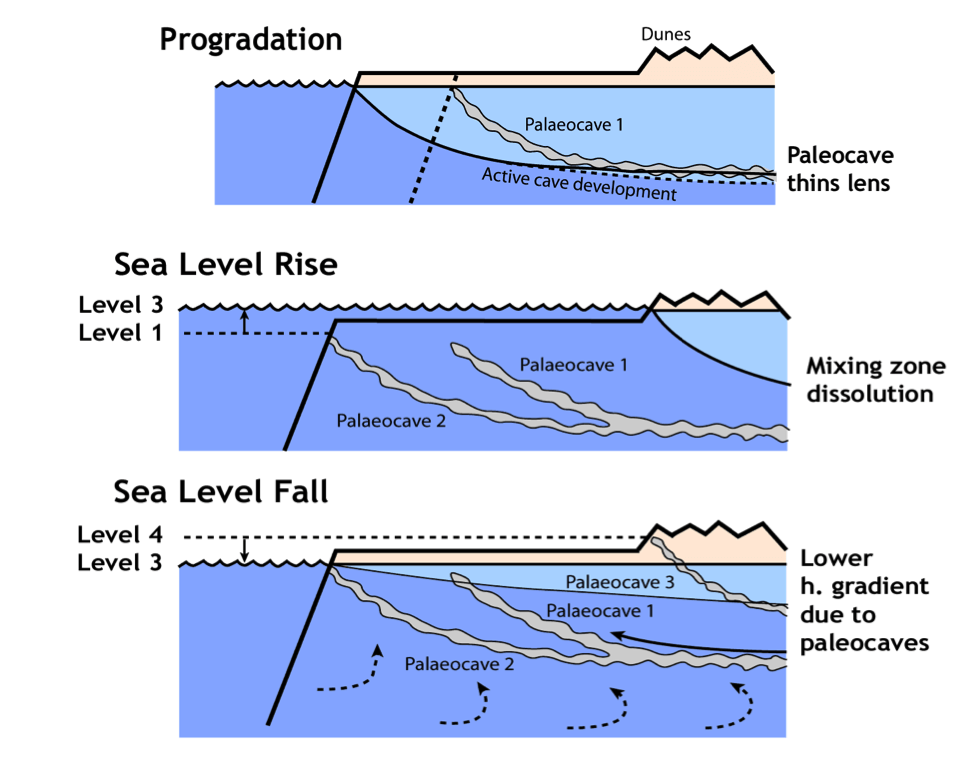

En este tipo de suelos, es común que sucedan procesos de disolución de la roca caliza, creando huecos y conductos que van creciendo con el paso del tiempo hasta formar extensas galerías subterráneas e intrincados sistemas de cuevas. A este proceso le llamamos carstificación, o karstificación, ya que el nombre viene de una localidad que ha servido como ejemplo para describir sus característicos paisajes: el karst o carso, en Eslovenia. Por esta razón, solemos escuchar que el tipo de suelo en la península es “kárstico” o “cárstico”, que es más propiamente un tipo de suelo en el que ha sucedido el proceso de carstificación. En realidad, este proceso sigue sucediendo en nuestros días.

La exploración sistemática de las cuevas subacuáticas de Quintana Roo comenzó en Tulum a mediados de la década de 1980. Diferentes equipos de buzos comenzaron a explorar los cenotes de la región y encontraron extensos pasajes que crecían a medida que unían sus registros.

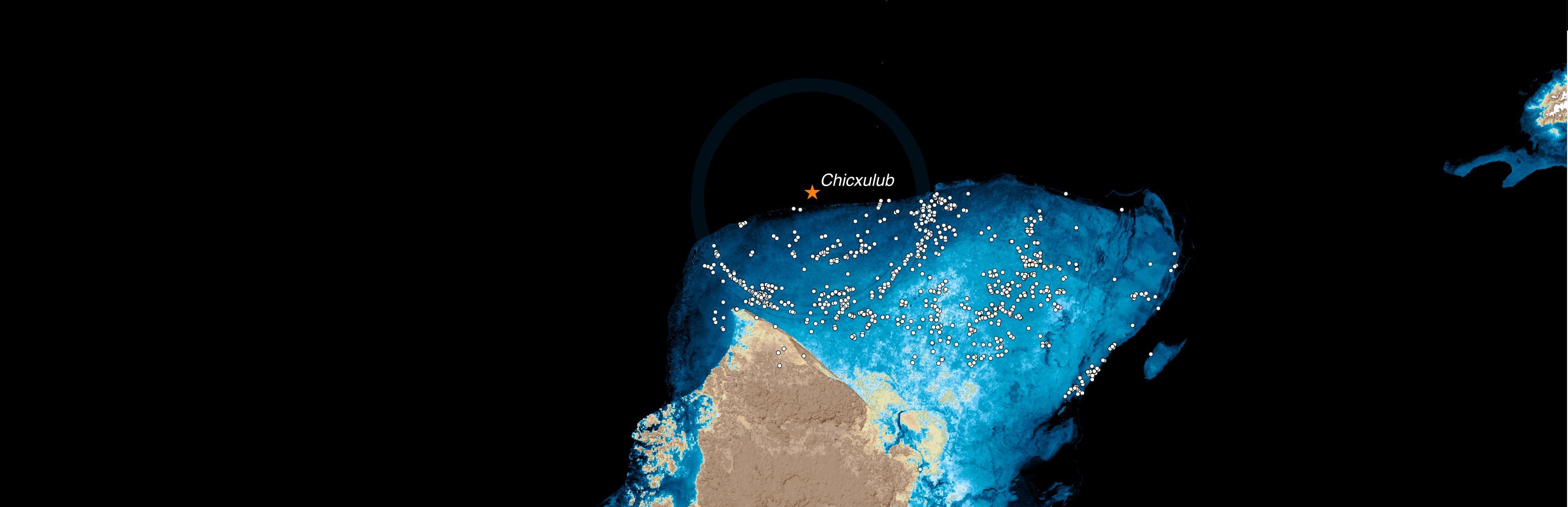

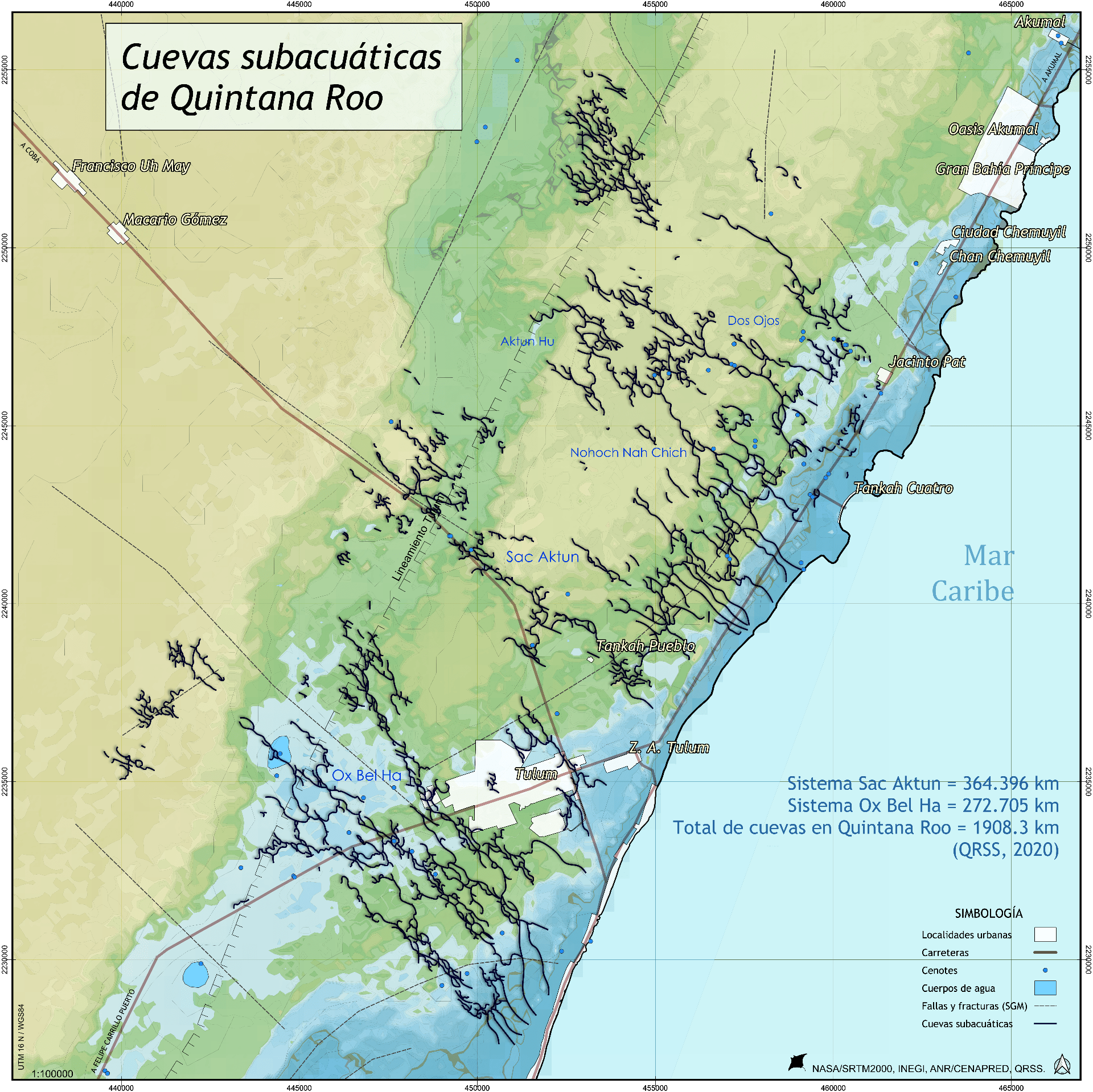

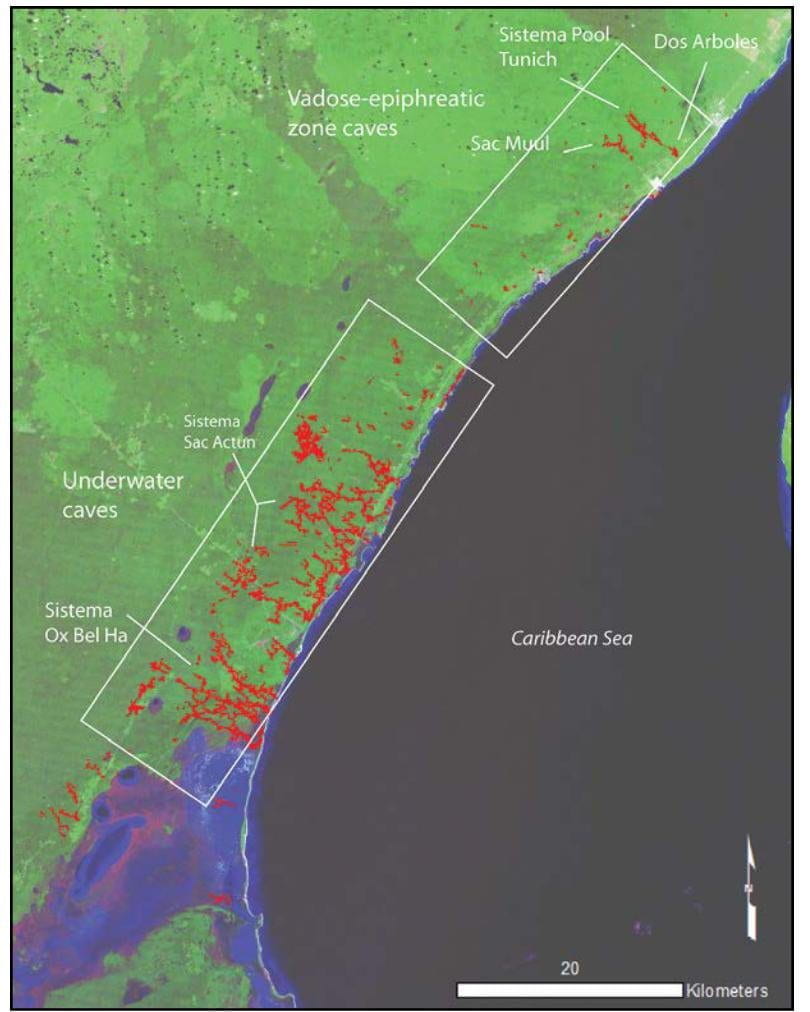

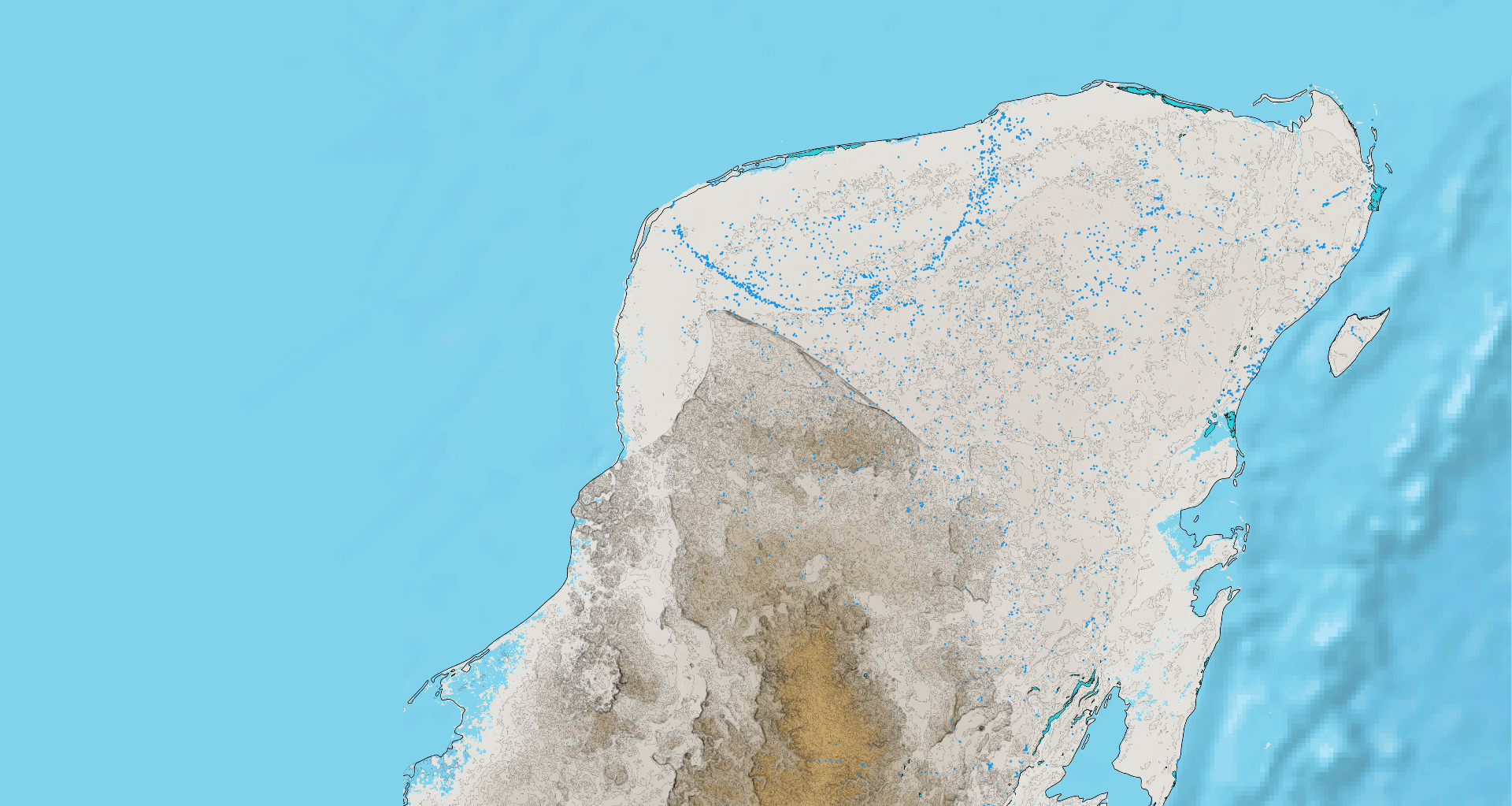

En el área de Tulum, han sido explorados poco más de 630 kilómetros de cuevas subacuáticas, mapeados en casi 35 años de exploración. En Quintana Roo existen unos 1,800 kilómetros de cuevas conocidas y faltan muchas por explorar (QRSS, 2019). El proyecto del Tren Maya debe garantizar su preservación. Considerar que la imagen presentada contiene datos del Atlas Nacional de Riesgos (CENAPRED/SEGOB) en donde las cuevas están desplazadas y distorsionadas al comparar con mapas originales de exploración.

En el área de Tulum, han sido explorados poco más de 630 kilómetros de cuevas subacuáticas, mapeados en casi 35 años de exploración. En Quintana Roo existen unos 1,800 kilómetros de cuevas conocidas y faltan muchas por explorar (QRSS, 2019). El proyecto del Tren Maya debe garantizar su preservación. Considerar que la imagen presentada contiene datos del Atlas Nacional de Riesgos (CENAPRED/SEGOB) en donde las cuevas están desplazadas y distorsionadas al comparar con mapas originales de exploración.

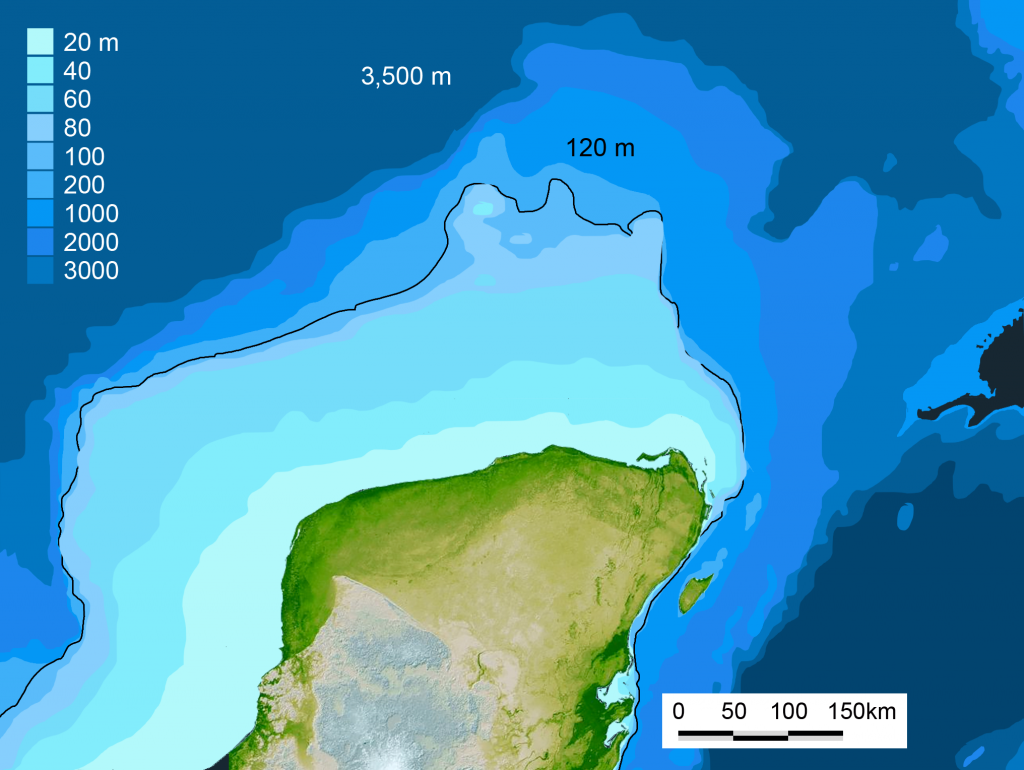

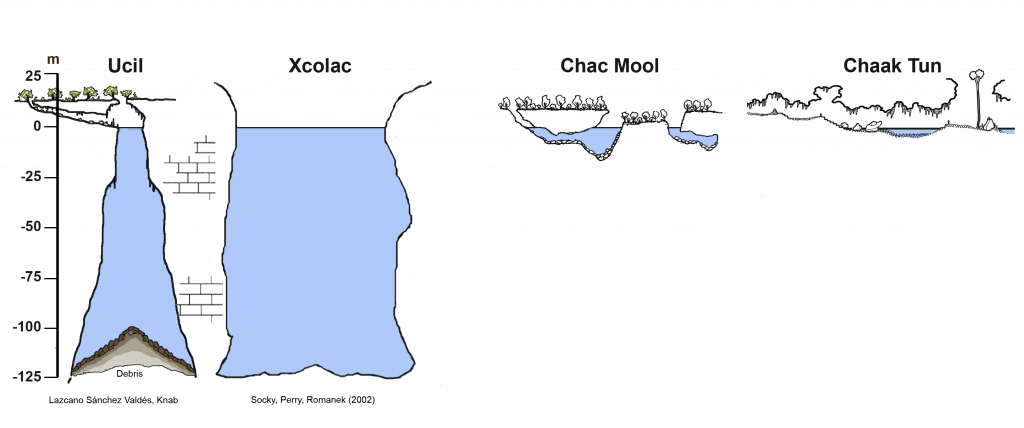

La cueva subacuática más larga del planeta Tierra se encuentra bajo el municipio de Tulum en Quintana Roo, México. Se extiende por más 360 kilómetros a una profundidad media de 21 metros y una máxima de 120 metros en una oquedad profunda llamada “El Pit”. El Sistema Sac Aktun, que significa “cueva blanca”, descarga el agua de lluvia infiltrada a través de la roca hacia el Mar Caribe en ojos de agua y en caletas como Xel Ha y Yalkú. Cuando desciende el nivel del mar, las cuevas antes llenas de agua se llenan de aire, perdiendo soporte y provocando el colapso y derrumbe del techo en diferentes secciones, creando puntos de acceso a la cueva. El Sistema Sac Aktun cuenta con más de 220 cenotes.

¿Cómo se formaron las cuevas y los cenotes

en la península de Yucatán?

Buzos exploran el sistema de cuevas subacuáticas Sac Aktun, debajo del área de Tulum. Foto: Proyecto Gran Acuifero Maya.

Buzos exploran el sistema de cuevas subacuáticas Sac Aktun, debajo del área de Tulum. Foto: Proyecto Gran Acuifero Maya.

Hallazgos antropológicos

El extenso sistema de cuevas bajo la península de Yucatán ha resultado ser un guardián de tesoros antropológicos y paleontológicos invaluables para aprender de la historia. Restos de animales pleistocénicos y humanos que datan de un tiempo muy anterior a la ocupación por la civilización Maya han sido encontrados en sus pasajes y galerías subacuáticas. Bajo el agua, estas cuevas proveen un ambiente único para la preservación de restos humanos y animales.

La mujer de Las Palmas crea nuevos interrogantes sobre cómo y cuándo llegaron nuestros antepasados a este continente.

La mujer de Las Palmas crea nuevos interrogantes sobre cómo y cuándo llegaron nuestros antepasados a este continente.

En 2006 fue encontrado el esqueleto casi completo (90%) de la “Mujer de Las Palmas” en otra cueva subacuática a 4.5 km de Tulum, que corresponde a una mujer entre 45-50 años de edad y 1.52 metros de estatura. Los hallazgos son piezas clave para entender el poblamiento del nuestro continente.

Unos años antes, en 2004 fueron encontrados los restos de la “Mujer de Naharon” de entre 20-25 años de edad, a 23 metros de profundidad y a 370 metros de distancia a la entrada más cercana, en el Sistema Naranjal. Sus restos fueron fechados en 13,600 años de antigüedad, aunque el dato se encuentra en disputa y actualmente se realizan otros fechamientos.

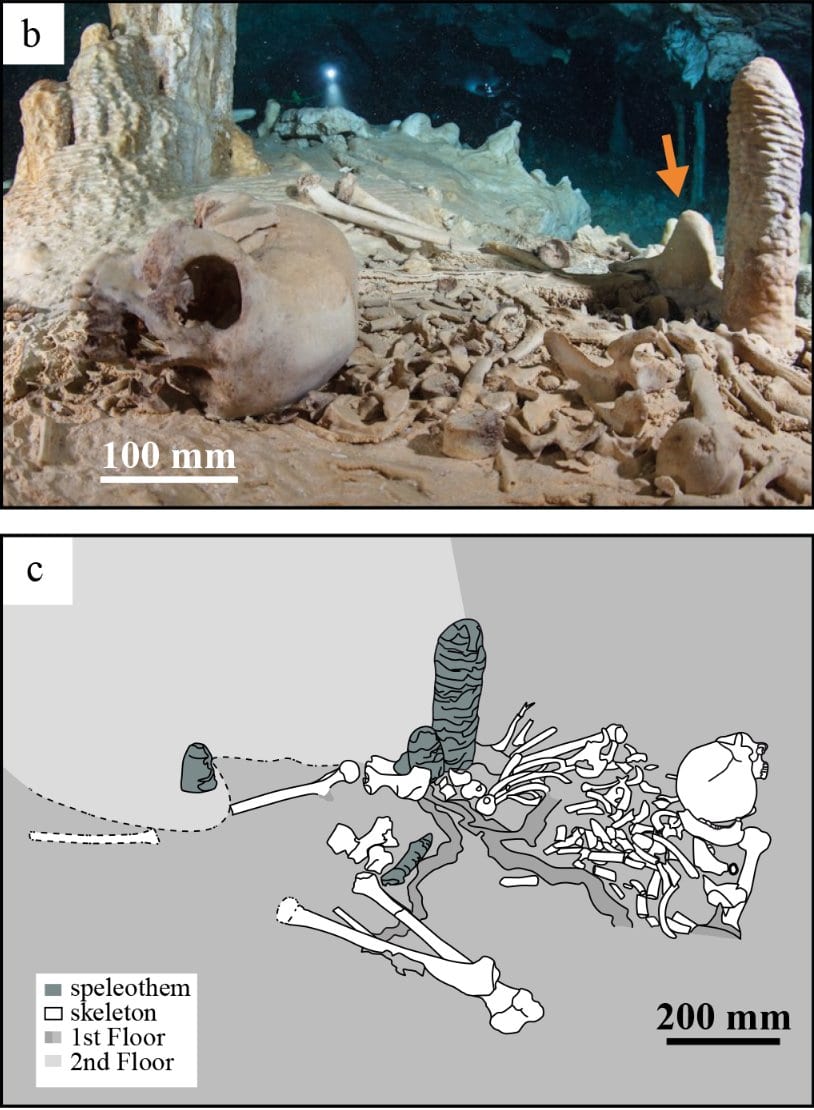

El sitio arqueológico de Chan Hol II antes de ser vandalizado. El esqueleto estaba originalmente completo y casi articulado. Fotografía de Nick Poole y Thomas Spamberg (Stinnesbeck et al., 2017).

El “Joven de Chan Hol” fue hallado en el cenote Chan Hol del Sistema Toh Ha de 32 km de longitud. El cuerpo fue colocado (posiblemente) en una ceremonia funeraria realizada al final del Pleistoceno, cuando el nivel del mar estaba 120m debajo y antes de que se inundaran las cavernas que el joven conoció y recorrió. Análisis de isótopos en un espeleotema asociado al hueso sugiere ~13,000 años de antigüedad. En febrero de 2012 diversos medios reportaron los hallazgos y unos días después, la cueva fue vandalizada y muchos huesos fueron robados entre el 16-23 de marzo por personas aún no identificadas. Por esta razón, muchas ubicaciones se mantienen en secreto.

La historia de Naia

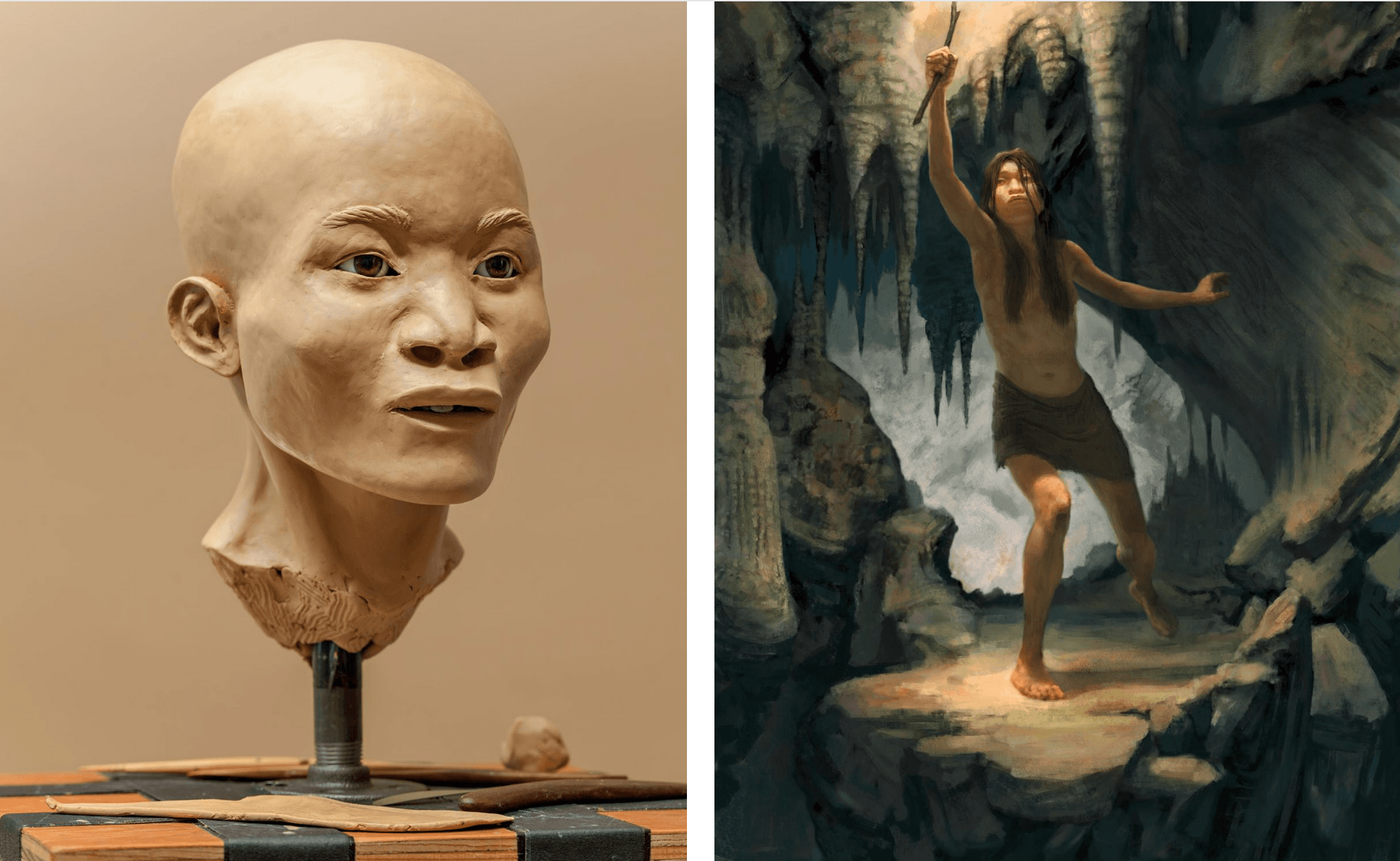

En marzo del 2008, en la sección Aktun Hu de Sistema Sac Aktun, en un lugar llamado “Hoyo negro” fueron encontrados a 42 metros de profundidad los restos de una mujer de entre 15-17 años de edad –de nombre Naia– con una antigüedad estimada entre 12,000 y 13,000 años.

Álvarez es uno de los buzos originales que descubrió Hoyo Negro, una cueva subacuática la península de Yucatán lleno de antiguos huesos humanos y animales. Años más tarde, regresó a Hoyo Negro como parte de la expedición para recuperar e investigar a Naia, uno de los esqueletos más antiguos y mejor conservados jamás descubiertos en las Américas.

Álvarez es uno de los buzos originales que descubrió Hoyo Negro, una cueva subacuática la península de Yucatán lleno de antiguos huesos humanos y animales. Años más tarde, regresó a Hoyo Negro como parte de la expedición para recuperar e investigar a Naia, uno de los esqueletos más antiguos y mejor conservados jamás descubiertos en las Américas.

Los buzos exploradores la encontraron en su tumba bajo el agua, junto a ella yacían restos de otros animales que fueron identificados como dientes de sable, gonfoterio (relacionado con el elefante moderno), tapir gigante, jabalí, oso, puma, gato montés, coyote, coatí y murciélago.

En años posteriores al hallazgo, buzos descuidados manipularon los restos y para evitar una mayor intromisión, los huesos se sacaron de la cueva entre 2014 y 2016, lo que permitió más estudios científicos. El análisis del ADN mitocondrial de Naia ha indicado un vínculo genético entre paleoamericanos y modernos nativos americanos.

Izq: La reconstrucción facial de Naia revela que los primeros humanos en pisar el continente no se parecían mucho a los nativos americanos, aunque la evidencia genética confirma su ancestro común. Der: La cueva estaba predominantemente seca durante la corta vida de Naia, ella pudo haber caído mientras exploraba sus oscuros pasajes. Recreación: J Chatters / Paleociencia aplicada: T McClelland / Fotografía: T Archibald / Arte (der): J Foster (National Geographic, 2015).

La datación por carbono 14 del esmalte de sus dientes arrojó una edad máxima para Naia de unos 12,900 años. Acumulaciones de carbonato de calcio que crecieron sobre los huesos de Naia han sido datados en 12,000 años por el método de uranio-torio (U/Th).

El sistema cárstico-antropogénico

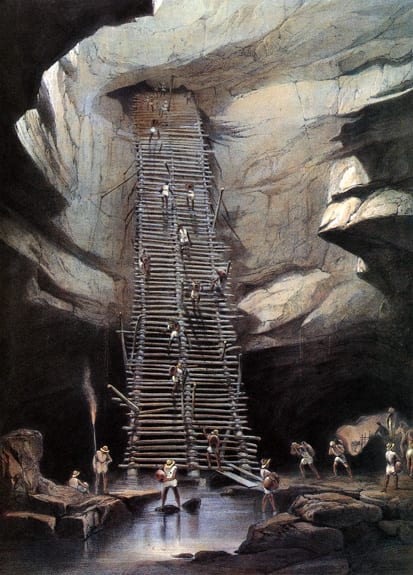

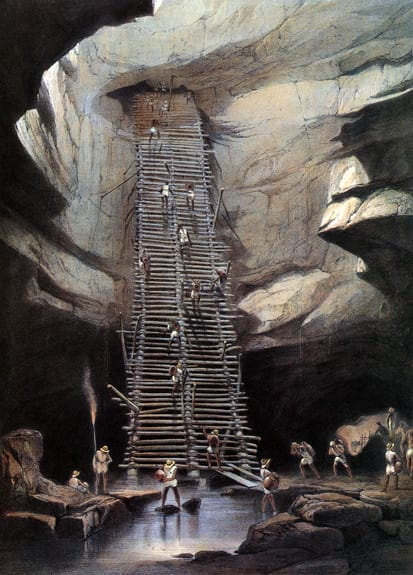

Las cuevas y cenotes de la península de Yucatán fueron utilizadas como alojamiento y para otras actividades desde hace mucho tiempo. De acuerdo con su uso, podrían subdividirse en santuarios, cuartos de servicio y lugares donde se extraía agua y sascab.

Cenote Xtacumbilxunan, en Bolonchén (‘nueve pozos de agua’) Campeche. Este pueblo escapó a la epidemia de cólera de 1833. La única fuente de agua dulce fluye en las profundidades debajo de gruesas capas de roca caliza. Litografía por H Warren. Imagen publicada en “Views of Ancient Monuments in Central America, Chiapas and Yucatan” – Frederick Catherwood (1844).

Cenote Xtacumbilxunan, en Bolonchén (‘nueve pozos de agua’) Campeche. Este pueblo escapó a la epidemia de cólera de 1833. La única fuente de agua dulce fluye en las profundidades debajo de gruesas capas de roca caliza. Litografía por H Warren. Imagen publicada en “Views of Ancient Monuments in Central America, Chiapas and Yucatan” – Frederick Catherwood (1844).

En la década de 1980, la Península de Yucatán, sobre todo el estado de Quintana Roo, experimentó el inicio del auge del desarrollo turístico y una gran transformación del sistema cárstico con un fuerte componente antropogénico.

Los sistemas de cuevas y cenotes están sujetas a destrucción mecánica por explosivos o maquinaria, como sucede en muchos sitios habilitados para “rafting” en cuevas freáticas (ríos subterráneos), lo que aumenta el impacto de contaminantes infiltrados hacia capas cada vez más profundas.

En la actualidad, el impacto en el paisaje cárstico de la península de Yucatán es considerable, asociado también a turismo y visitas intensivas a zonas arqueológicas, cuevas y cenotes.

Punta Cancún, donde corre una porción de la zona hotelera de Cancún.

Punta Cancún, donde corre una porción de la zona hotelera de Cancún.

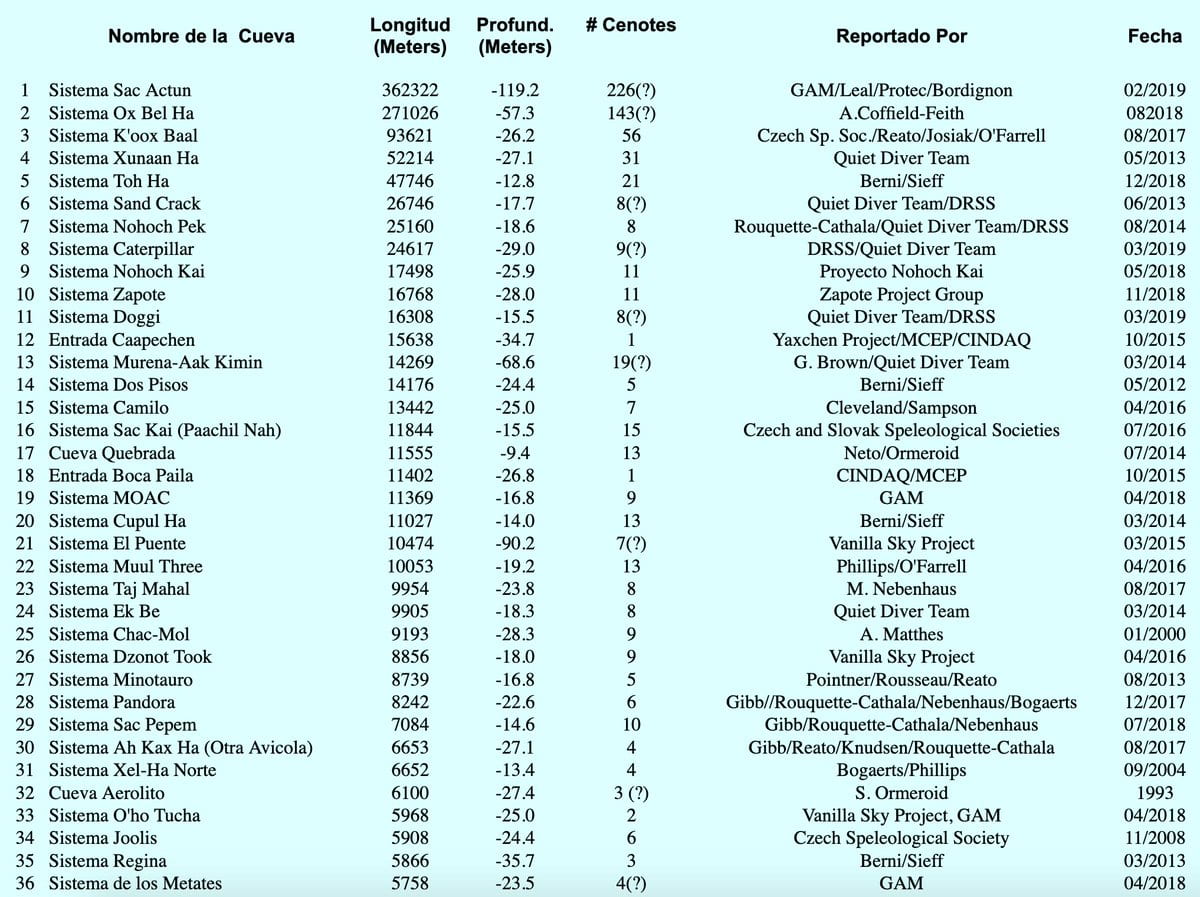

El Tren Maya, en caso de concretarse, deberá sortear de forma segura los retos técnicos de pasar sobre las cuevas subacuáticas más grandes del planeta, como los sistemas Sac Aktun y Ox Bel Ha. Como éstos, existen decenas de sistemas a lo largo de la costa oriental del estado de Quintana Roo.

El listado más completo y sus mapas asociados, que existe de los sistemas subterráneos de Quintana Roo, es el que publica “Quintana Roo Speleological Survey” (QRSS).

Fuente: QRSS. Actualizado 18/julio/2019.

Fuente: QRSS. Actualizado 18/julio/2019.

Sistema hidrogeológico

El Sistema Sac Aktun es solamente una de tantas cuevas que descargan el agua dulce de la lluvia infiltrada bajo el suelo hacia el Mar Caribe, actúan como drenajes naturales. Colapsos en diferentes zonas del techo han formado más de 220 cenotes, utilizados con fines comerciales y recreativos alrededor del área de Tulum.

Sistema Sac Actun. Fotografía: Archivo Gran Acuífero Maya (GAM)/INAH.

El área que contiene a Sac Aktun tiene una densidad de cuevas de 2.9 km/km². En el área de Ox Bel Ha, la densidad de cuevas alcanza 5.2 km/km². Estos sistemas de cuevas mantienen el balance hidrológico de la zona descargando el agua infiltrada de la lluvia hacia el Mar Caribe.

Distribución de cuevas y densidad de zonas subacuáticas y de vadosa en la costa oriental de Quintana Roo (Kambesis, 2016).

Distribución de cuevas y densidad de zonas subacuáticas y de vadosa en la costa oriental de Quintana Roo (Kambesis, 2016).

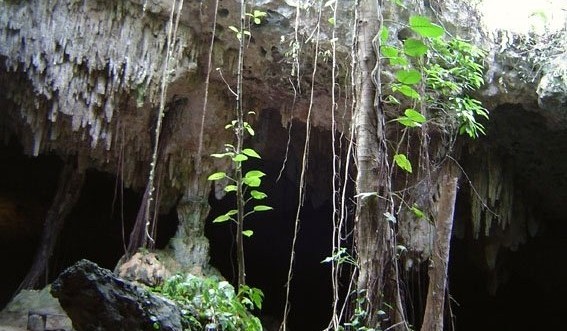

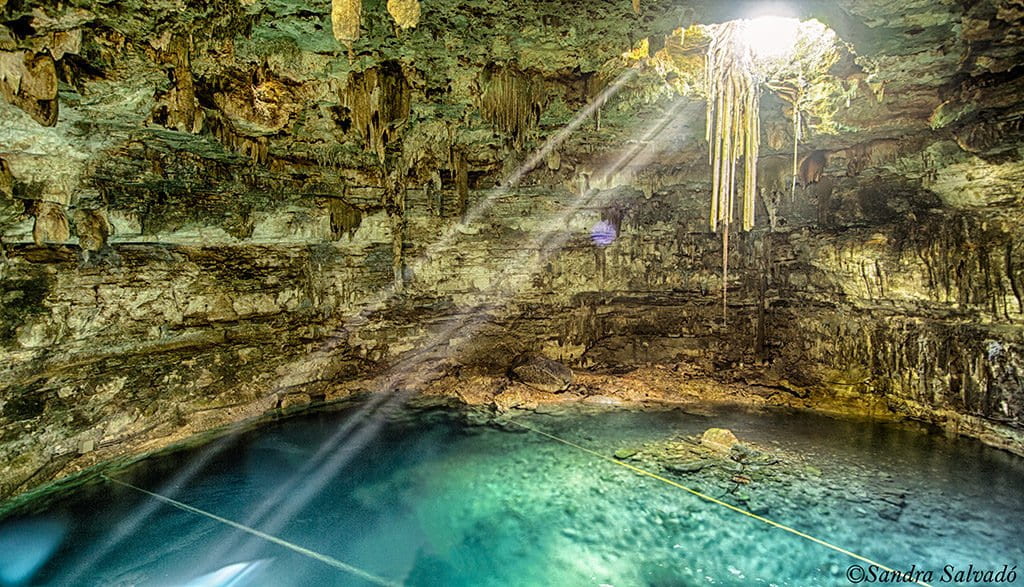

Hoy en día, el término “cenote” se emplea para designar cualquier espacio subterráneo con agua y que contenga una ventana hacia el exterior. Los cenotes se forman cuando delgadas secciones del techo sufren derrumbes, colapsan sobre las cavidades a lo largo de la cueva, creando nuevas entradas al mundo subterráneo.

En el cenote Samulá en Valladolid, Yucatán, se puede observar perfectamente en el suelo la pila de rocas que colapsaron del techo. También se observan estalactitas recientes y raíces bajando desde la superficie en busca de agua.

Cenote Samulá. Fotografía:@Caminomascorto.

Cenote Samulá. Fotografía:@Caminomascorto.

Por ejemplo, en el cenote Suytun también cerca de Valladolid, aprovecharon las rocas del colapso para construir una plataforma para los visitantes.

Cenote Suytun. Imagen: Fun&Travel

Cenote Suytun. Imagen: Fun&Travel

Las secciones del techo que colapsan pueden ser pequeñas o muy grandes, conduciendo bajo la tierra hacia amplias galerías o estrechos pasajes llenos de agua. Los cenotes también son entradas de luz y materia orgánica dentro del sistema hidrogeológico, interactuando con el agua subterránea.

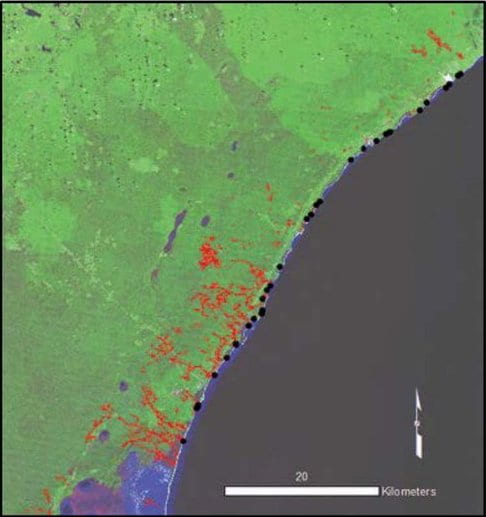

Como vimos, los sistemas de cuevas subacuáticas descargan el agua infiltrada en la selva hacia el Mar Caribe. En algunas ocasiones, se desploman grandes secciones del techo de las cuevas cerca de la costa formando “caletas”, como las muy conocidas Xel Ha, Xcaret y Yalkú, con grandes flujos de agua subterránea hacia el océano.

También puede darse el caso de que las cuevas se extiendan más allá de la línea de costa y descargan el agua ‘dulce’ directamente por oquedades en el fondo somero del mar. Entonces les llamamos “ojos de agua” que son muy comunes, por ejemplo, en la laguna arrecifal de Puerto Morelos.

Distribución de descargas costeras y ojos de agua en el noreste de Quintana Roo. Los punto negros son ojos de agua y las líneas rojas son sistemas de cuevas (Kambesis, 2016 / Datos de cuevas: QRSS).

Distribución de descargas costeras y ojos de agua en el noreste de Quintana Roo. Los punto negros son ojos de agua y las líneas rojas son sistemas de cuevas (Kambesis, 2016 / Datos de cuevas: QRSS).

Ojo de agua en Puerto Morelos, Quintana Roo.

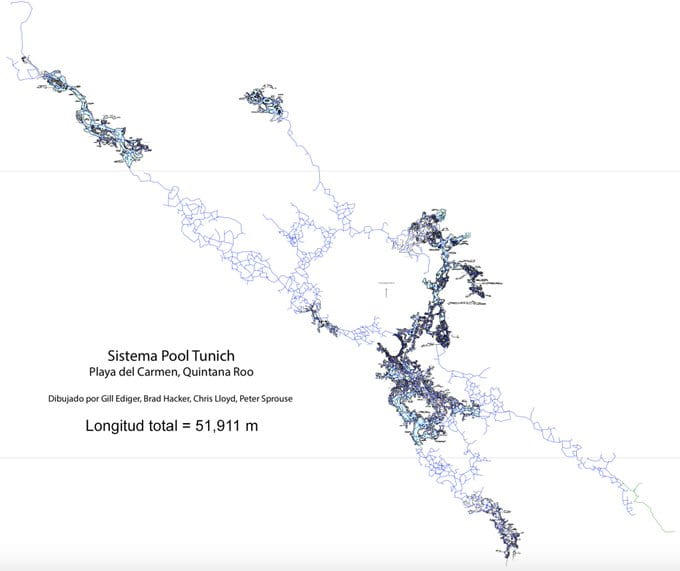

Entre Akumal y Playa del Carmen, han sido registrados 330 km de pasajes en más de 250 cuevas secas, algunas justo por encima del nivel actual del mar y que se encuentran en la zona epifreática que sufre inundaciones periódicas. siendo el más grande el Sistema Pool Tunich (Río Secreto) con 51.9 kilómetros de longitud. Dentro de esta área de 234 km², la densidad de cuevas es de 0.5 km/km².

Sistema Pool Tunich (Río Secreto). Peter Sprouse Teams, 2018.

Sistema Pool Tunich (Río Secreto). Peter Sprouse Teams, 2018.

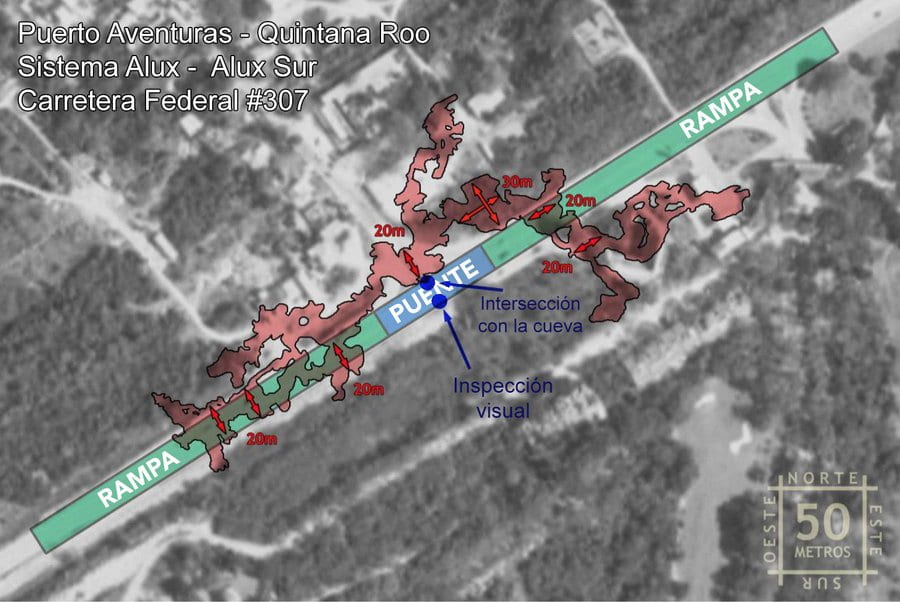

Otros sistemas de cuevas secas son Sistema Sac Muul y Sistema Alux, el cual se extiende por debajo de la carretera federal #307 a la altura de Puerto Aventuras.

Sistema Alux Sur. Puerto Aventuras, Quintana Roo (Alux Survey Team, 2008).

Sistema Alux Sur. Puerto Aventuras, Quintana Roo (Alux Survey Team, 2008).

Riesgos en el karst

En algunos lugares el espesor del techo es menor a 1.5 metros. Dentro de la cueva es posible escuchar a los automóviles pasando por encima en la carretera. Así como el Sistema Alux, existen un gran número de cavidades a lo largo de la carretera #307 ya que coincide con la cresta de playa, el borde con mayor elevación.

Los colapsos suceden de forma natural y no avisan; son difícilmente predecibles. Puede aumentar su frecuencia si no existen controles que garanticen la seguridad de las construcciones. Podemos minimizar los riesgos asociados tomando en cuenta las características de la zona.

La alta densidad de cuevas y cenotes dentro del área conurbada de Tulum es una amenaza directa a la construcción de desarrollos masivos turísticos y de vivienda debido a que en muchas secciones el techo de la cueva es muy delgado. La protección del Sistema Sac Aktun – y de otros tantos igual de importantes en la región – del impacto humano involucra y requiere serias regulaciones en el tratamiento de aguas residuales en la Riviera Maya y regulación en las construcciones, además de una continua investigación y monitoreo hidrogeológico del acuífero cárstico de la región. Debe, sin duda, incluirse en las políticas de desarrollo regionales y tomarse en consideración para futuros proyectos turísticos y de transporte.

Para lograr un aprovechamiento sostenible de estos sistemas, es necesario un entendimiento integral de los cenotes, las cuevas, el movimiento del agua subterránea y su interacción con las rocas que forman el acuífero, la influencia del océano y sus mareas (es decir, el estudio del sistema hidrogeológico completo de la península); también es necesario evaluar el impacto de las zonas urbanas y las posibles causas de contaminación de la única fuente de agua con la que contamos, que es precisamente el agua subterránea. Esta búsqueda debe darse por convergencia entre las ciencias ambientales, ciencias del agua, ciencias de la tierra, ciencias biológicas, el estudio y conservación de la red subterránea de conductos, conocimiento acumulado en las comunidades, explotación eficiente de recursos y, por supuesto, la exploración y aprovechamiento sostenible mediante buceo de cuevas.

Es necesario realizar sondeos directos e indirectos y levantamientos topográficos específicos para conocer la ubicación, no solamente de los extensos sistemas de cuevas, sino de cavidades puntuales y dispersas, muy abundantes en toda la región kárstica, para cualquier proyecto de infraestructura de gran envergadura.

“Adentrarse en una cueva es una experiencia inolvidable. Las cuevas nos hablan de geología, bioquímica, paleontología y arqueología. Las cuevas nos enseñan historia, nos motivan a conocerlas y a pensar en su futuro.”

Tierra de cenotes

Manera sugerida de citar este artículo:

Monroy-Ríos E (2019) Por las Rutas del “Tren Maya”. Karst Geochemistry and Hydrogeology – Blog personal. Publicado el 4 de agosto, 2019. Fecha de consulta: [dd/mm/aa].

https://sites.northwestern.edu/monroyrios/2019/08/04/rutas-01

Referencias

Kambesis P & Coke JG (2016) The Sac Actun System, Quintana Roo, Mexico. Boletín Geológico y Minero127(1):177-192.

Lebedeva EV, Mikhalev DV, & Nekrasova LA (2017) Evolutionary stages of the karst-anthropogenic system of the Yucatán Peninsula. Geography and Natural Resources38(3):303-311. doi:10.1134/S187537281703012X

QRSS (2018) List of Long Underwater Caves in Quintana Roo Mexico. Quintana Roo Speleological Survey. National Speleological Society (NSS). Consultada el 12 de julio de 2019.

Stinnesbeck W, Becker J, Hering F, Frey E, González AG, Fohlmeister J, et al. (2017) The earliest settlers of Mesoamerica date back to the late Pleistocene. PLoS ONE12(8): e0183345. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0183345

Veni, G. (1990) Maya Utilization of Karst Groundwater Resources. Environmental Geology and Water Sciences16(1):63-66. doi:10.1007/BF01702224

Conferencia

Diálogo con Ingenieros – Colegio de Ingenieros Civiles de México A.C.

POR LAS RUTAS DEL TREN MAYA: ALGUNOS RETOS TÉCNICOS. DR. EMILIANO MONROY-RÍOS. CICM.