Written by: Rodger Ling

“Most of the small percentage of accidents involving experienced cave divers have occurring during deep cave dives.”

– Sheck Exley

Basic Cave Diving: A Blueprint for Survival

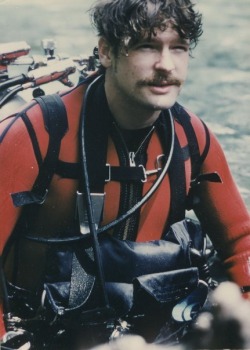

It would be interesting to know what, if anything, Reinhold Messner would have to say about the death of Sheck Exley. Exley, a 45-year-old mathematics teacher from Live Oak, Florida, died on April 6, 1994 as he attempted to descend to a depth of over 1,000 feet in a cave in Mexico.

It is tempting to draw comparisons between the two men, Exley the cave div er and Messner the mountain climber. Each had a well-earned reputation for being the best in their chosen endeavor. Over the years both men saw contemporaries perish; early in their careers, both watched their own brothers die in front of them, Messner’s high in the mountains and Exley’s deep in the clear waters of Wakulla spring. Today Messner, although very much alive, suffers the effects of oxygen deprivation from breathing the rarified air of the upper atmosphere; while Exley is dead from breathing the thick air of great depth.

er and Messner the mountain climber. Each had a well-earned reputation for being the best in their chosen endeavor. Over the years both men saw contemporaries perish; early in their careers, both watched their own brothers die in front of them, Messner’s high in the mountains and Exley’s deep in the clear waters of Wakulla spring. Today Messner, although very much alive, suffers the effects of oxygen deprivation from breathing the rarified air of the upper atmosphere; while Exley is dead from breathing the thick air of great depth.

Open the books to the longest and deepest underwater caves in America, and Exley’s name will inevitably appear. While no one would argue that cave diving is without risk, Exley demonstrated that it could be done safely if practiced with knowledge, care, and skill. He literally “wrote the book” (several books, actually) on safe cave diving practices. He was the first in the world to log over 1,000 cave dives. In over 29 years of cave diving, he made over 4,000.

Like Reinhold Messner, Exley seemed to have a sixth sense, an uncanny ability to know when to push on and when to retreat. Like Messner, there were times when he seemed almost invulnerable, too smart to be caught in the traps that killed others.

Sheck Exley particularly excelled at pushing back the traditional cave diving barriers of distance and depth. At Cathedral Canyon Spring in Florida, a site which had such potential that Exley bought the property and moved there, he achieved a world record penetration of over two underwater miles during an eleven and a half hour solo dive in 1990.

Exley was equally famous for his expertise at deep diving, an even more technical and formidable challenge. As depth increases, divers must breath air at ever higher pressures. Under pressure, the nitrogen in ordinary air causes narcosis, a kind of drunkenness that increases with depth. Even life-giving oxygen becomes poisonous at depths greater than 200 feet (although Exley, one of the few to dive much below 400 feet on compressed air and live through the experience, had a demonstrated tolerance to it).

The most practical solution for those who must dive at great depth is the use of special gas mixes such as Trimix, which lower the oxygen and nitrogen content while substituting another inert gas such as helium. While early experiments using mixed gases in the U.S. had tragic outcomes (Exley’s friend Louis Holtzendorf died on one such dive), Exley’s deep dives at a Mexican spring known as Nacimiento del Rio Mante soon proved the worth of Trimix for cave diving. Not only could these mixtures allow a diver to go deeper without succumbing to narcosis or oxygen poisoning, but they also reduced the amount of time spent at decompression stops during the ascent.

Beginning in 1979, Exley methodically worked his way deeper into the cave at Rio Mante. In March of 1989, using Trimix, he descended to a world record depth of 881 feet, returning to the surface after 14 hours of decompression with no harmful effects. Only commercial divers, working from diving bells which supplied their breathing mixture through umbilical tubes and provided shelter for days or weeks of decompression (a level of support not possible in a cave) had ever been deeper.

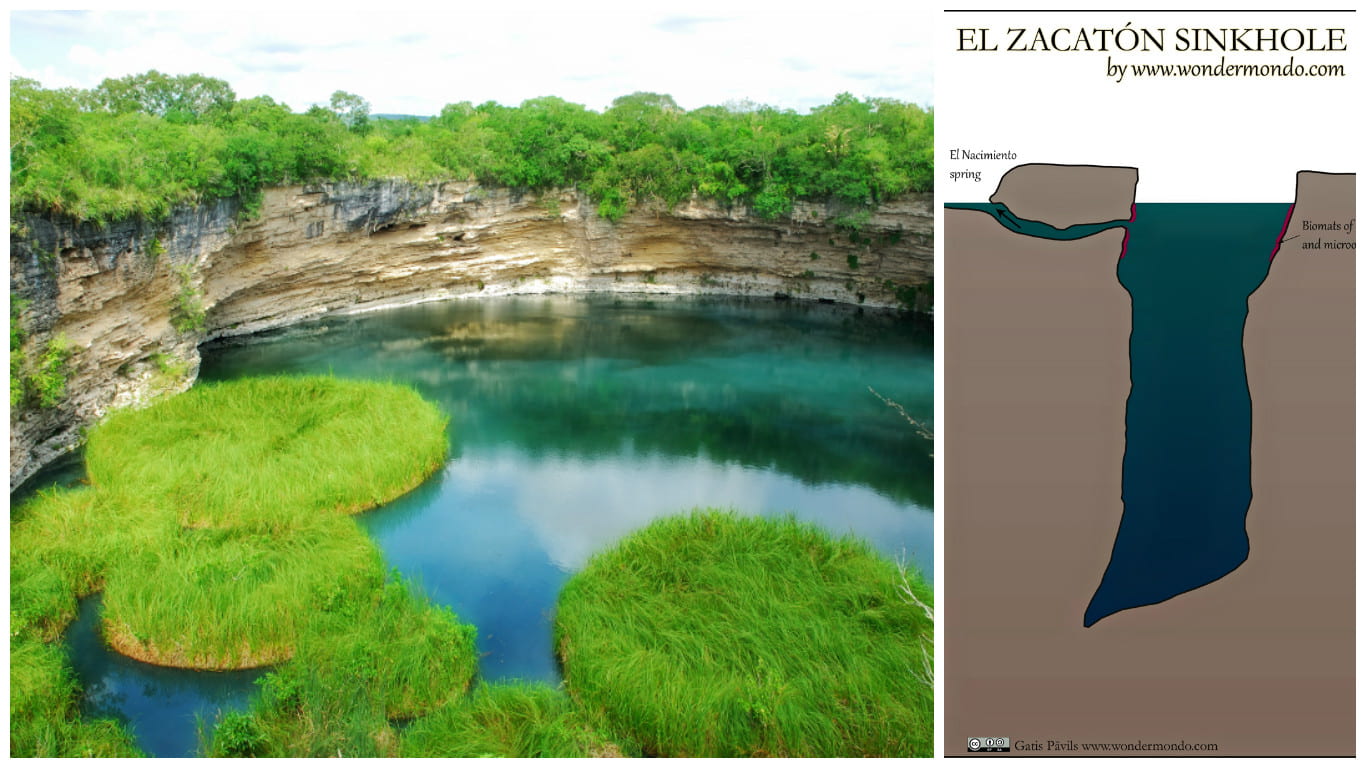

In later years Exley and his team continued their explorations of deep caves and springs. In August of 1993, Exley reached 863 feet when he touched bottom in Bushmansgat (Bushman’s Hole), South Africa, but not before experiencing a serious case of high-pressure nervous syndrome (HPNS) that included blurred vision and intense, uncontrollable tremors. Soon after, he joined Jim Bowden in focusing his efforts on a cave known as Zacatón (aka Pit 6350), north of Tampico, Mexico that was known to be at least 1,080 feet deep. In September, Bowden dove to 774 feet in the dark, warm waters of the spring. Ann Kristovich, the team physician, descended to 541 feet, a new depth record for women (the old record had been set at Rio Mante by Mary Ellen Eckoff, Exley’s wife). Following the September expedition, the team announced that despite over 30 dives at great depth, they had encountered no pressure-related problems. Dives of over 1,000 feet, it was said, were planned for the future. The number has a nice ring to it. A thousand feet would be a milestone, a necessary one if anyone was ever to reach the bottom of Zacatón. By the time Exley returned to Mexico in the spring of 1994, the number 1,000 must have been etched into his brain.

On April 6, 1994, Jim Bowden and Sheck Exley entered the water at Zacatón. After months of meticulous calculations and planning, their descent would be over within a few moments. While it’s been a tradition in cave diving for these kinds of attempts to be made solo, Bowden and Exley dove simultaneously, following separate weighted lines 25 to 30 feet apart but still essentially alone in the murky water. There was little hope of even seeing one another; they may as well have been diving solo. In 11 minutes, Bowden had reached 898 feet but was lower than expected on gas reserves and turned upward to begin over nine hours of decompression. Kristovich, acting as a support diver, was hanging in the water high above, watching the two streams of bubbles. Eighteen minutes into the dive, she saw that the bubbles coming from Exley had stopped. Exley’s wife Mary Ellen descended to 279 feet, where a ledge might have blocked the flow of bubbles. There were none.

What happened to Sheck Exley in those 18 minutes? The physiology of making such a rapid descent to great depth is not yet completely known or understood, and when solo divers perish they typically leave few or no clues. Following the accident, it was assumed that Exley’s body would never be recovered. Those who knew him well were certain of one thing: whatever happened, Exley did not panic. More than once in the past Exley had jeopardized his own life to save another, his steel nerves prevailing over the most nightmarish of conditions. “He was the ultimate cool,” Bowden told a Texas newspaper.

But Sheck Exley still had one more surprise for the world. When the guideline was pulled from the cave three days after the dive, his body came up with it, the line wrapped intentionally around his arms and the valves of his side-mounted tanks.

Later, the members of the team published a detailed analysis that concluded Exley probably fell victim to “HPNS, oxygen induced incapacitation or a convulsion” or some combination of those events (see www.iucrr.org/aa_misc.htm). Both of Exley’s primary tanks were exhausted, as was one of his two side-mounted tanks (the other was untouched). The team conjectures that for unknown reasons Exley ran out of gas in his primaries and was forced to switch to the side-mount “travel mix” that was far less appropriate for that depth, making a bad situation worse. His dive computer showed a maximum depth of 879 feet; it’s not clear if he was able to ascend past that point. With his bouyancy compensator fed by the empty main tanks, any ascent would require extra effort. At some point he wrapped the line around himself to stabilize his position but ultimately lost consciousness before he could deal with the situation. At similar depths in Bushmansgat he had reported HPNS tremors so intense that he had difficulty with even simple tasks such as operating the inflator. I imagine Exley hanging there trying to fight back the darkness until the side tank ran out–this could be just a minute or two at that depth–and by then he may have been too incapacitated to get another regulator into his mouth. As in most tragedies there was probably no single factor but simply a disastrous combination of things that not even Sheck Exley could overcome–but no one can really know for sure.

So how do you mourn a man who died pushing the limits of an endeavor most people consider foolhardy at best? What can you say about a person who knew the immensity of the risks and yet went anyway? “He died doing something he loved and did better than anyone else in the world,” Bowden said later. Perhaps that’s all that anyone can or should say. The Sheck Exleys and Reinhold Messners of this world weigh the risks, consider the consequences, and make their choices without asking for our consent or our pity.

Did Exley die in the mindless pursuit of a meaningless record, or was he a pioneer who was advancing our understanding of diving at great depths? I’d like to think Reinhold Messner would be inclined to say the latter. One of Exley’s friends described him as a man who was always trying to see around the next corner. He dove to ever-greater depths because the caves he explored demanded it, because something that most of us will never quite understand compelled him forward.

There are so few unexplored places left in the world, so few true explorers!

Addendum, July 2005

I read this week with fascination and dread a story in the August 2005 issue of Outside magazine about the death of Australian Dave Shaw in Bushmansgat, South Africa. Years earlier, Exley had been to over 880 feet deep in the cave, having a close call with helum-induced tremors. In October 2004 Shaw descended to 886 in the huge underwater shaft using a rebreather and had discovered the body of Deon Dreyer, a diver who had blacked out and disappeared ten years previously. Shaw was determined to return and bring the body up, and in January 2005 he returned to do just that. Although he had just seven years of diving experience against Exley’s decades, Shaw had calculated and planned in what seems to me a very Exley-like fashion. On the surface he assembled a strong team and placed a decompression chamber attended by a physician. Ropes hung ready to hoist a striken diver up from the water, with support divers and emergency gas supplies all the way down past 400 feet.

Shaw’s plan was simple: descend to the body using the line he had previously tied off, slide it into a special body bag, attach the line, and surface after spending a maximum of five minutes on the bottom. Exactly what went wrong might still be a mystery, except that Shaw wore a video camera on his head that recorded his every movement. At these extreme depths, the smallest detail–even the wearing of the camera itself–could have deadly consequences. Watching the tape later, his friends concluded that Shaw simply let himself work a little bit too hard, get just a little bit out of breath, and that started a downward spiral that killed him.

From the Outside article by Tim Zimmerman:

“Still, Shaw keeps checking the time on his dive computer. After five and a half minutes on the bottom, he’s aware enough to know he has to leave, but he doesn’t get far. The video shows the bottom moving beneath him. Then Shaw’s forward progress stops. His errant cave light has apparently snagged the cave line tied to Deon’s tanks. Shaw knows he has caught something, and turns awkwardly. His breathing starts to sound desperate. He pulls at the cat’s cradle of cave line, as if trying to sort it out. Every breath is now a sharp grunt. Shaw struggles to move again but is anchored by the weight of Deon’s body. The shears are still in his hand, but he never cuts anything. The pace of his breathing keeps accelerating, and there is a tragic, gasping quality to it, so painful to listen to that Herbst and Shirley will no longer watch the video with sound. Twenty one minutes into the dive, the sounds finally start to fade. Dave Shaw, with carbon dioxide suffusing his lungs, is starting to pass out. He is dying. It’s heartbreaking to watch. A minute later there is no movement.”

The almost spooky end to the story is that four days later, after the emergency tanks had been recovered and the lines pulled, Shaw’s body floated up from the darkness with Dreyer in tow, making good on his promise to bring him home.

Deep diving seems to hold a deathly fascination for many. Typical the victim is a newer diver, but not always: witness the bizarre descent into the madness of diving deep on simple compressed air that in 1997 killed a legend in diving: Rob Palmer.

A handful of technical divers continue to push the limits of deep diving, although perhaps appropriately, sophisticated robots became primary explorers at Zacatón. The late John Bennett was the first to break 1,000 feet on open-circuit scuba gear, but this and other dives were in the ocean, not in a freshwater cave. As Numo Gomes said in 1994, “Four divers in the world have undertaken dives below 200 meters (656 feet); one is dead, another is paralyzed from the waist down, and the other two suffered DCS during their respective deepest dives.” A new depth record for open-circuit scuba was set in July 2005 by Pascal Bernabe, who reached 330 meters (1,082 feet) in the ocean off Corsica.

Written by: Rodger Ling

More

Deep, Dark and Deadly – The perils of cave diving didn’t spare even the sport’s greatest star. By Michael Ray Taylor.