For months, veterinarians put medicine into the animals’ quarantine habitats at Chicago’s Shedd Aquarium, ensuring that animals entering the building did not bring dangerous pests or pathogens with them. And for months, the medicine consistently kept disappearing. Where was it going? Who was taking it? And what was their motive?

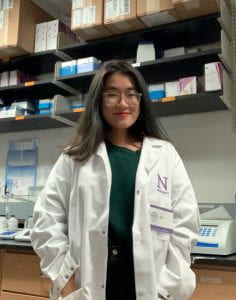

To help solve this classic whodunnit mystery, researchers at Shedd Aquarium partnered with Northwestern University microbiologists to collect clues, follow leads and ultimately track down the culprit.

After conducting microbial and chemical analyses on samples from the saltwater aquarium systems, the team found it was not just one culprit but many: A family of microbes, hungry for nitrogen.

“Carbon, nitrogen, oxygen and phosphorous are basic necessities that everything needs in order to live,” said Northwestern’s Erica M. Hartmann, who led the study. “In this case, it looks like the microbes were using the medicine as a source of nitrogen. When we examined how the medicine was degraded, we found that the piece of the molecule containing the nitrogen was gone. It would be the equivalent to eating only the pickles out of a cheeseburger and leaving the rest behind.”

The research was published online Saturday (Oct. 2) in the journal Science of the Total Environment.

An expert on indoor microbiology and chemistry, Hartmann is an assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering at Northwestern’s McCormick School of Engineering.

Safety first

When any new animal enters Shedd Aquarium, it first must undergo a quarantine process before entering its permanent residence. This allows the aquarium’s veterinarians to observe the animal for potentially contagious diseases or parasites without risking harm to other animals at the facility.

“Shedd Aquarium’s quarantine habitats behind-the-scenes are a first stop for animals entering the building—allowing us to safely welcome them in a way that ensures outside pathogens are not introduced to the animals that already call Shedd home,” said Dr. Bill Van Bonn, vice president of animal health at Shedd Aquarium and a co-author of the study. “We are grateful to have partnered with Northwestern University to scientifically explore what’s happening in our quarantine habitats microbially to inform how we manage them and continue to provide optimal welfare for the animals in our care.”

Anti-parasitic drug was ‘mysteriously vanishing’

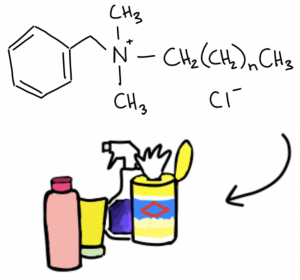

During this quarantine process, all animals receive chloroquine phosphate, a common anti-parasitic medicine. Veterinarians proactively add it directly to the water as a pharmaceutical bath to treat a variety of illnesses. After adding chloroquine to water, aquarists then measure the medicine’s concentration. This is when they realized something was off.

“They need to maintain a certain concentration in the habitats to treat the animals effectively,” Hartmann said. “But they noticed the chloroquine was mysteriously vanishing. They would add the correct amount, then measure it and the concentration would be much lower than expected — to the point where it wouldn’t work anymore.”

Aquarists from Shedd Aquarium collected water samples and swab samples and sent them to Hartmann’s laboratory. Swab samples were collected from the sides of the habitats as well as from the pipes going in and out of them. In total, the team found about 754 different microbes.

“There are microbes in the water, obviously, but there also are microbes that stick to the sides of surfaces,” Hartmann said. “If you have ever had an aquarium at home, you probably noticed grime growing on the sides. People sometimes add snails or algae-eating fish to help clean the sides. So, we wanted to study whatever was in the water and whatever was stuck to the sides of the surfaces.”

Studying ‘leftovers’ from the meal

By studying these samples, the Northwestern and Shedd Aquarium teams first determined that microbes caused the medicine to disappear and then localized the responsible microbes. Hartmann’s team cultured the collected microbes and then provided chloroquine as the only source of carbon. When that experiment’s results were inconclusive, the team performed sensitive analytical chemistry to study the degraded chloroquine.

“If the chloroquine was being eaten, we were essentially looking at the leftovers,” Hartmann said. “That’s when we realized that nitrogen was the key driver.”

The unusual suspects

Out of the 754 microbes collected, the researchers narrowed it down to at least 21 different guilty suspects — belonging to the phyla Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Chloroflexi and Proteobacteria — living inside the habitats’ outlet pipes. Some of the microbes even appear to be brand new and never before studied.

“We couldn’t nail down a single culprit, but we could isolate the specific location,” Hartmann said. “Our findings determined that just flushing the quarantine habitats with new water would not be enough to fix the problem because the responsible microbes were clinging to the sides of the pipes.”

Hartmann said the pipes might need to be scrubbed or replaced in order to prevent chloroquine from disappearing in the future. Another potential solution might be regularly switching between freshwater and saltwater because microbes are typically sensitive to one or the other.

“Everyone at Shedd Aquarium is obviously very committed to the health and wellbeing of the animals they house as well as really excited about research,” Hartmann said. “It was super cool to work with them because we were able to help the animals and possibly discovered some new organisms.”

The study, “Towards understanding microbial degradation of chloroquine in large saltwater systems,” was supported by the Searle Leadership Fund and the Helen V. Brach Foundation.

This story was originally posted on Northwestern Now.