Author: Mike Pastuovic (michaelpastuovic2023@u.northwestern.edu), Weinberg ’23

Nowadays, it is rare to get through a weekend of football without hearing announcers vaguely refer to “the numbers” in regards to teams deciding to go for two or go for it on 4th down in their own territory. Untraditional, analytically driven decisions have become more and more commonplace in football over the last decade or so, culminating in the explosion in the number of two-point conversion attempts in the 2020 NFL Regular Season, outlined by ProFootballTalk. This analytics revolution is already in its adolescence, and it seems as if mainstream media outlets either have very little willingness or very little ability to explain how it is affecting decision-making on a week-to-week basis at both the collegiate and professional levels.

Contrary to what a broadcast might normally lead on, many of these decisions can be understood with just a bit of contemplation, sans fancy models. With some pretty simple decision trees, we can gain insight into why these decisions are so quickly gaining popularity. For the rest of this article, I will discuss a prolific, often misunderstood phenomenon of the analytics revolution: going for two down eight.

For the purposes of this article, we will assume that there will only be one more score in the game following the try: another touchdown by the trailing team.

There are a couple of key assumptions that teams make when deciding to go for two down eight (down fourteen prior to touchdown). First, they assume that the only other future scoring event that’s effect would be altered by the decision to go for two would be their next touchdown. In other words, they assume that another score by the opponent (making it again a two-possession game) would effectively end the game, regardless of the outcome of the attempted two-point conversion. Additionally, they often assume that there is insufficient time remaining to realistically score more than one more time. This is why you will often see teams going for two very late in games.

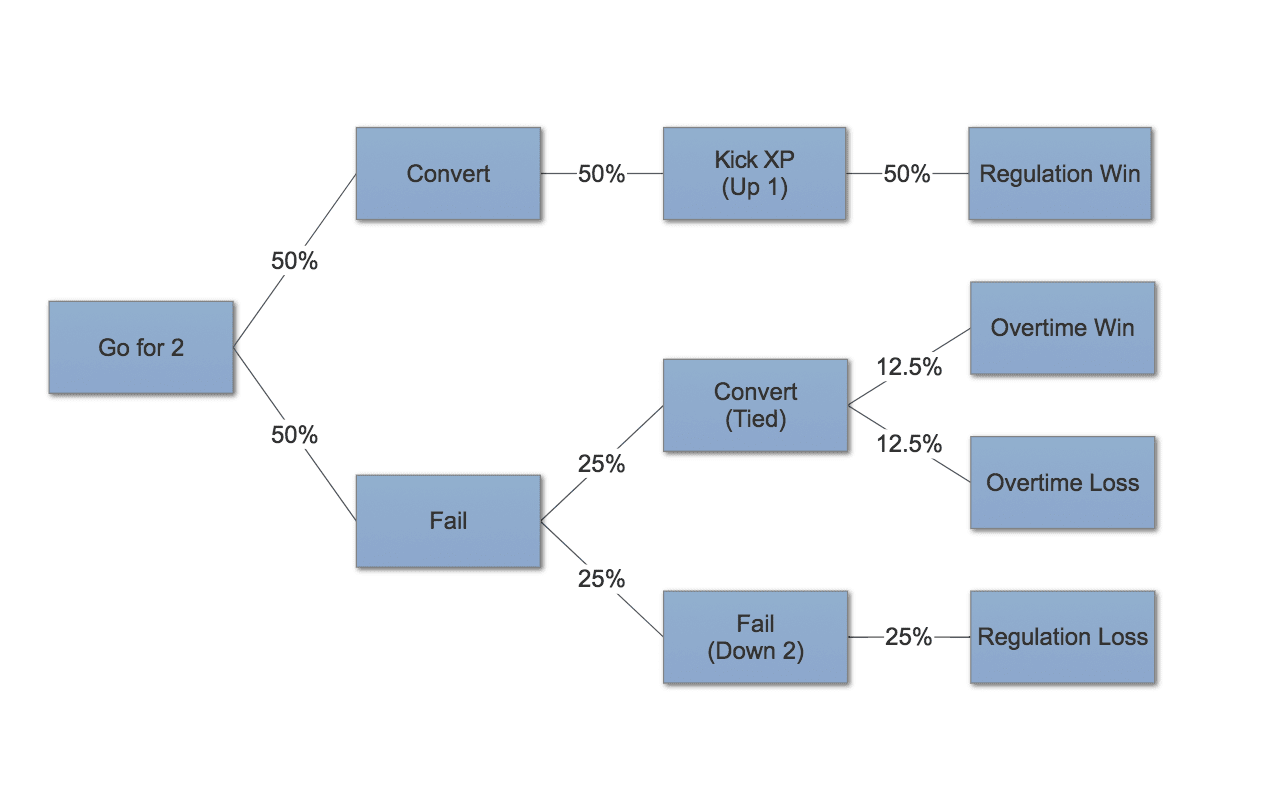

Teams also assume that they will convert two-point conversions just about half of the time, and make their extra points just about every time. With the assumption that the team trailing by eight will score another touchdown (the only remaining score of the game), we can look at this decision tree, made by Kevin Cole of Predictive Football, to see why it often makes sense for teams to go for two late in games.

With the assumptions that teams convert two-point conversions half of the time and extra points every time, and that the only future score is another touchdown by the trailing teams, Cole’s decision tree outlines how going for two down eight is in most cases, the correct decision late in games. With a successful two-point try after being down eight, you are guaranteed to win in regulation half of the time (given our assumptions). Even if you miss on your first attempt, you still have a 50% shot to convert your second attempt and send the game to overtime. Teams will miss their first attempt and convert their second 25% of the time. Unfortunately, teams will miss both attempts 25% of the time. We see the team will win 50% of the time, lose in regulation 25% of the time, and go to overtime 25% of the time. Now, we assume that an average team would have a .500 winning percentage in overtime, and would therefore win in overtime 12.5% of the time. With this decision tree, we see that an average team can expect a .625 winning percentage (with our assumptions) after deciding to go for two, as opposed to the .500 winning percentage they would have had if they had gone with conventional wisdom, kicking the extra points and flipping a coin in overtime.

With the assumptions that teams convert two-point conversions half of the time and extra points every time, and that the only future score is another touchdown by the trailing teams, Cole’s decision tree outlines how going for two down eight is in most cases, the correct decision late in games. With a successful two-point try after being down eight, you are guaranteed to win in regulation half of the time (given our assumptions). Even if you miss on your first attempt, you still have a 50% shot to convert your second attempt and send the game to overtime. Teams will miss their first attempt and convert their second 25% of the time. Unfortunately, teams will miss both attempts 25% of the time. We see the team will win 50% of the time, lose in regulation 25% of the time, and go to overtime 25% of the time. Now, we assume that an average team would have a .500 winning percentage in overtime, and would therefore win in overtime 12.5% of the time. With this decision tree, we see that an average team can expect a .625 winning percentage (with our assumptions) after deciding to go for two, as opposed to the .500 winning percentage they would have had if they had gone with conventional wisdom, kicking the extra points and flipping a coin in overtime.

Certainly, these numbers are not exact, as the two-point conversion rate is not exactly 50% and kickers at times miss extra points. However, this rough .125 difference in expected winning percentage is significant, and teams across football have clearly taken notice.

Now that we have intuition for why teams go for two down eight, let’s get into the weeds a little more and see exactly how much of a bump in expected win percentage average teams experience when they do go for it (once again, given our assumptions). Here, we are going to assume the team being examined is exactly average in relevant categories, including two-point conversion percentage, extra point make percentage, and expected win percentage in overtime. Via Sporting News, across the 2018 and 2019 NFL seasons, teams converted two-point conversions 49.4% of the time, while they made extra points 94.1% of the time. We also assume this average team has a .500 expected win percentage in overtime.

We have four different possible paths when going for two down eight (assuming teams act optimally given very objective decisions): one that leads to a win in regulation, two that lead to overtime, and one that leads to a loss in regulation.

Table 1

| Path | 2-pt good, XP good | 2-pt good, XP no good | 2-pt no good, 2-pt good | 2-pt no good, 2-pt no good |

| Outcome | Regulation Win | Overtime | Overtime | Regulation Loss |

| Calculation | (.494)*(.941) | (.494)*(1-.941) | (1-.494)*(.494) | (1-.494)*(1-.494) |

| Probability | .464854 | .029146 | .249964 | .256036 |

As seen in Table 1, there is a .464854 chance of winning in regulation, a .27911 chance of overtime (.29146+.249964), and a .256036 chance of losing in regulation for an average team when they go for two down eight, given our assumptions. We can now compare this to the probabilities associated with kicking an extra point down eight.

Table 2

| Path | XP good, XP good | XP no good, 2-pt good | XP good, XP no good | XP no good, 2-pt no good |

| Outcome | Overtime | Overtime | Regulation Loss | Regulation Loss |

| Calculation | (.941)*(.941) | (1-.941)*(.494) | (.941)*(1-.941) | (1-.941)*(1-.494) |

| Probability | .885481 | .029146 | .055519 | .029854 |

As seen in Table 2, there is a .914627 chance of overtime (.885481+.029146), and a .085373 chance of losing in regulation (.055519+.029854) for an average team when they kick the extra point down eight, given our assumptions.

Next, using our assumption that this average team has an expected win percentage of .500 in overtime, we can get each of the respective overall expected win percentages (for going for two down eight and for kicking the extra point) down to a single number. This way, we can say exactly how large of a difference the decision to go for two down eight makes, given our assumptions.

Starting with going for two, we have determined that there is a .464854 chance of a regulation win, and a .27911 chance of overtime. Giving the team a .500 expected win percentage in overtime, teams that go for two down eight have a .604409 chance of winning the game (.464854+.27911*(.500)). Meanwhile, we have determined that if this average team kicks the extra point down eight, there is a .914627 chance of overtime and a .085373 chance of losing in regulation. Giving the average team a .500 expected win percentage in overtime, teams that kick the extra point down eight have a .4573135 chance of winning the game ((.914627)*(.500)).

As we see, there is a very significant difference of .1470955 in expected win percentages (.604409-.4573135) for average teams that decide to go for two down eight, and those that decide to kick the extra point, given our assumption that the only remaining score in regulation will be another touchdown by the trailing team.

The primary motivation for this article was the Steelers’ Week 15 decision to kick the extra point down eight with 5:32 left in the Fourth Quarter against the Bengals on Monday Night Football. Knowing that Steelers’ Head Coach Mike Tomlin is considered one of the better coaches in the NFL, I was curious about the rationale for this call. I wondered if he figured that Pittsburgh’s chance in overtime against an in theory inferior Cincinnati opponent was so high that it actually made sense to kick the extra point and play for overtime.

To test this theory, we can solve for the breakeven expected overtime winning percentage, where teams should be indifferent between kicking the extra point and going for two when down eight points. Solving for this value, we can then determine whether Tomlin and the Steelers could have reasonably thought that their probability of winning in overtime was high enough to justify kicking the extra point, instead of going for two. We can again use the league average extra point conversion percentage and two-point conversion percentage, as it is fair to assume K Chris Boswell and the Pittsburgh offense are not significantly distant from league average in these categories.

Replacing our previous expected win percentage for an average team (.500) with a variable x, we can set the winning percentage associated with going for two down eight equal to the winning percentage associated with kicking the extra point down eight, given our assumptions.

Going for two = Kicking Extra Point

.464854 (Regulation W) + .27911*X (Overtime) = .914627*X (Overtime)

Solving for X, X =.73145801

So, the necessary expected win percentage in overtime to justify kicking the extra point is .73145801, a very high proportion, especially when considering the randomness associated with a coin toss and great variability in NFL overtime results. Given our original assumptions, and assuming relatively average team two-point conversion and extra point percentages, it is extremely hard to justify not going for two down eight very late in games, unless they have reason to believe they have an extraordinarily high chance of winning in overtime.

Because of this, we can conclude that Tomlin’s decision had more to do with an old school mentality rather than a statistical analysis. It could potentially make sense for a future team to kick the extra point down eight if they think they are especially poor at two-point conversions, have a great kicker, and have a good chance in overtime. All else equal, it is a no brainer for teams to go for two down eight late in games.

Sources: Sporting News, Predictive Football, ProFootballTalk

Insightful read. The tables gave a great explanation of the calculations. Kudos

Excellent article. Very easy to follow and love the data behind the argument!