Deering Library

The Charles Deering Library succeeded Lunt as Northwestern University’s main repository for books. Lunt Library (now Lunt Hall), erected in 1894 as the university’s first library building, had become overcrowded, noisy, and inefficient by the mid-1920s. Theodore W. Koch, the University Librarian from 1919 to 1941, undertook a campaign for a new library building just when Northwestern was about to initiate a fifty-year, one-hundred-million-dollar development plan. A new library was to be the campaign’s first objective. Koch envisioned a facility that would “measure up to Coleridge’s idea of a library: ‘a living world, and every book a man, absolute flesh and blood.’” A faculty library committee was formed, headed by Professor James A. James, who worked closely with Koch throughout the planning process.

Charles Deering, 1935.

The Deering and McCormick families, of International Harvester fame, united by both business alliance and marriage, were long-time supporters of Northwestern. William Deering, a president of the University’s Board of Trustees, had funded the construction of Fisk Hall in the 1890s. His son Charles, chair of the Board of Directors of International Harvester, a man “of scholarly tastes and habits,” had previously endowed a professorship in Botany. When Charles died in 1927, he left Northwestern a bequest of one million dollars, to be used for a project of the University’s choosing. The Deerings and McCormicks readily approved the use of the bequest for a new library. Additional gifts came from Charles’s widow, Marion Whipple Deering, and their children, Marion Deering McCormick, Barbara Deering Danielson, and Roger Deering. Although Charles Deering’s frequent donations to the University had been anonymous during his lifetime, the family assented when the Board of Trustees proposed to name the new library for him.

With the funding secured, Theodore Koch visited libraries around the country and consulted many architects. The final design, drawing on Koch’s and James’s recommendations, came from James Gamble Rogers, the architect of many of Northwestern’s most beautiful structures. Rogers and members of his New York-based firm collaborated with Koch and various committees, including those of the University trustees, faculty, and library staff, on space planning.

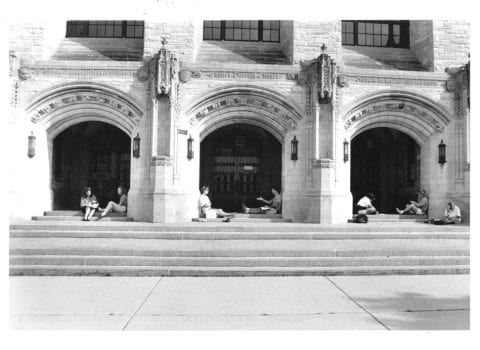

The site chosen for the Charles Deering Library, along the crest of a low ridge, had previously been occupied by Heck Hall, a dormitory which had burned down in 1914. Although the new facility would have space for 500,000 volumes, the floorplan was designed to facilitate easy expansion when needed, either by adding east-west wings to the north and south, or by an eastward extension of the main building. Groundbreaking for the new library took place in June, 1931; the cornerstone was laid by twelve-year-old Roger McCormick on January 12, 1932. Deering Library was dedicated on December 29, 1932 and officially opened on January 3, 1933.

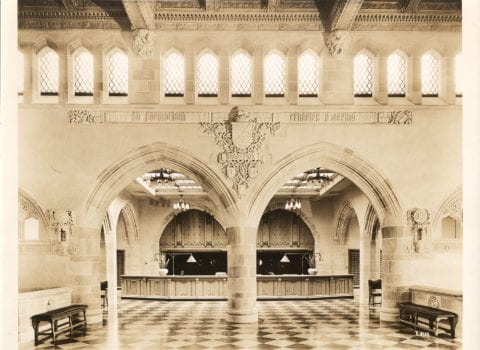

The style of the magnificent new structure was Norman Gothic, reminiscent of King’s College Chapel at Cambridge, England. The style, also known as “collegiate Gothic,” set the tone for much future construction at Northwestern. The Deering and McCormick funds made it possible to build a lavishly detailed facility, constructed of a dazzling variety of materials. Bedford limestone from Indiana and Wisconsin Lannon stone (the same Dolomitic limestone used in Rogers’s Women’s Quadrangle, the Sigma Alpha Epsilon building, and the Western Theological Seminary) were shipped to the workshop of Adam Groth and Sons in Joliet, where craftsmen worked the stone before sending it to Evanston for the exterior walls. The interior stone was Briar Hill sandstone from Ohio and Winona Travertine from Minnesota. The steps to the front entrance were of granite from Cold Spring, Minnesota, while the loggia was paved in was George Washington sandstone from Alexandria, Virginia. Most of the interior wood trim was Appalachian white oak from West Virginia.

Artists and artisans enhanced the interior and exterior surfaces with symbols drawn from the world of learning, reflecting T.W. Koch’s whimsical nature. Rene Chambellan decorated wood, stone, and plaster with owls, mice, lamps, pens, scrolls, books, and hourglasses. The stained and painted glass in the tall Gothic windows were executed by G. Owen Bonawit, who drew his inspiration from the seals of great universities; gods and savants from India, China, and Persia; industry and transportation; poetry and fable; and noted Americans from Pontiac and Tecumseh to Abraham Lincoln. Bronze and marble busts were placed throughout the library, including sculptures of Homer, Shakespeare, Tennyson, Carlyle, Walter Scott, Voltaire, Rousseau, Moliere, William Pitt, and Washington.

Koch Gardens, 1920s.

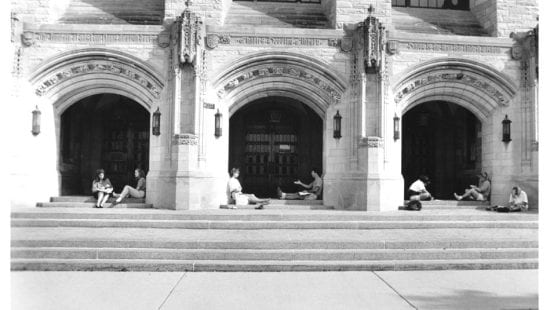

The grounds were planned with equal care. The original plan called for a “moat” on the the north, west, and south sides of the building, to be planted as gardens and to serve as “open-air reading rooms” in warm weather. The gardens that were eventually laid out were named the Koch Memorial Gardens in 1943, after the librarian’s death. The garden on the south side of the building underwent extensive restoration in 1996 and was renamed the Koch-Ericson Garden to memorialize librarian Rolf Ericson. The south garden holds a statue of the goddess Diana (by sculptor Anna Hyatt Huntington); a statue of the goddess Ceres stands in the north garden.

The finished Charles Deering Library was a source of great pride to the University community, hailed as an aesthetic and scholastic triumph. Over time, the interior spaces were altered considerably to meet changing needs and growing collections. Within ten years of its completion, Deering Library was already beginning to feel the shortage of space for its patrons and collections that had plagued Lunt two decades earlier. It wasn’t until the 1960s that a new building campaign was launched, with a new library as a top priority.

Once the new University Library opened in 1970, students no longer entered the library through Deering’s impressive arches. The original entry level of Deering became the second floor, and people now enter Deering on the former lower level, connected to the University Library by a long corridor. Still, Deering Library continues to be a campus landmark. It also holds some of the Library’s special libraries and collections of distinction—including the Art Collection and the Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections and University Archives.