In These Our Days:

Cultural Context for The Triumphs of God’s Revenge

The Triumphs was published and sold for over a century in early modern England, cultivating its own enduring community of readers and reflecting the broader values and interests of its culture. John Reynolds wrote the original text of The Triumphs with an acute awareness of the religious and political climate of his era; his work also bears thematic similarities to local and national events that were being discussed in the burgeoning popular print market. Assessing the context in which The Triumphs was created and first consumed allows contemporary readers to interpret many more facets of the murderous tales.

Early Modern English Protestantism, Anti-Spanish Sentiment, and the Spanish Match

Example of a Murder by a Corrupt Priest, Father Justinian

Unknown artist, “Adrian / Justinian / both devide Lauriers money / burne his clothes / and bury him,” copper engraving, in John Reynolds, The Triumphs of God’s Revenge […] (London: Printed for R. Gosling, and Sold by J. Osborn, 1726), History XXVII, 414 (edited excerpt).

John Reynolds’ Christian perspective is integral to his conception of crime and justice throughout The Triumphs of God’s Revenge. Reynolds remains committed to his stated moral purpose for the book: beyond emphasizing the role of the devil behind the murders and the role of God behind the stories’ resolutions, he includes many biblical references and inserts didactic, religious commentary into many of his narratives. In History XVI, Reynolds describes a guilty character’s refusal to admit to committing a murder while being questioned by authorities. He explicitly states why this is the wrong spiritual choice:

“That if he were guilty of his accusation, he had no better plea then [sic] confession, nor safer remedy than repentance. That contrition is the true mark of a true Servant of God, and though we fall to Nature and Sin as being men, yet we should rise again to grace and righteousness as being Christians.”

(Reynolds, The Triumphs of God’s Revenge, History XVI, 230.)

Implicit in this commentary is the conflation of the religious confession of sin with the legal confession of a crime. Such a notion reflects a society with no meaningful separation between Church and State power, such as that of early modern England. During this era, scholar Gregory Durston writes that “Christianity was ‘part’ of the common law”;1 as such, God’s providence in the face of sinful humanity was a victorious force that required attention and action on the part of God’s people. However, Reynolds’ estimation of God’s people diverged sharply between Protestant and Catholic lines, reflecting a similar religious divide in early modern English culture and politics.

Reynolds writes The Triumphs from an explicitly Protestant stance. Although many sects of Christianity existed in early modern England, Reynolds appears to specifically address a Protestant audience in his book, especially by criticizing Catholicism and Catholic-majority states in continental Europe. Such criticism is sometimes offhand; in History VIII, he briefly mentions “the Jesuites (who as the Mountebanks and Panders of Kingdoms and Estates, leave no Invention, nor Ceremony unattempted, to seduce and bewitch the affections of the world),”2 herein accusing the Catholic clergy—and perhaps also the church at-large—of greed.3 By contrast, in History XVII, two villains flee to “the strong City of Geneva (which depends not of France or Savoy, but of God and it self)….” In the same paragraph, even the villains “observe it to be a City exceeding, politiquely, vertuously, and religiously governed….”4 During this era, Geneva was a Reformed stronghold in Europe. Influenced strongly by famous theologians and residents John Calvin and Theodore Beza, it developed the nickname “Protestant’s Rome.” Here it is favorably contrasted to France and the Duchy of Savoy, both neighboring Catholic entities, and praised for its Protestant theocratic governance.

Other anti-Catholic sentiment in The Triumphs is more inflammatory. In History X, an Italian history, Reynolds includes the following passage as an aside in his description of a murderer attempting to escape:

“As he was swiftly galloping thorow Campo de Fuogo (the publick place where the Pope (that Antichrist of Rome) burns the children of God for the profession of the glorious Gospel)[…]”

(Reynolds, The Triumphs of God’s Revenge, History X, 129.)

By the early seventeenth century, anti-Catholic sentiment was common among English Protestants like John Reynolds, and the perceived threat of Catholic influence upon England fomented widespread animosity toward Catholic-majority nations in continental Europe, particularly Spain. In the wake of Elizabeth’s strained, sometimes bellicose relationship with Spain in the sixteenth century5 (and the concurrent rise of anti-Catholic persecution in the Elizabethan era), English Protestants likely reacted with trepidation when the newly crowned James I began to publicly pursue diplomatic relations with Spain in the early seventeenth century. Perhaps most famously, James I pursued a marriage between one of his sons (first Prince Henry, then Charles) and the Spanish Infanta, Maria Ana,6 a years-long negotiation referred to as the Spanish Match. Although this marriage never occurred, the Protestant English public reacted with consternation to this proposed union in the 1610s and early 1620s. Parliament echoed the public’s anxiety, releasing a treatise evaluating the potential benefits and downfalls of the Spanish Match in 1621.7

John Reynolds was an outspoken critic of Spain; his controversial 1624 pamphlet Vox Coeli specifically condemned the much-maligned Spanish ambassador to England, Diego Sarmiento de Acuna, Count of Gondomar.8 Historian Berta Cano-Echevarria argued that, in The Triumphs, Reynolds set most of his murder tales in Catholic-majority countries like Italy and Spain to obliquely critique them; in the era of the Spanish Match, it may not have been a coincidence that many of Reynolds’ murders revolved around romances, serving as cautionary tales that showed the dire consequences of bad marriages.9 Although Reynolds set more of his histories in Italy and France than in Spain, his other publications reinforce his anti-Spanish beliefs and may inform an overall reading of The Triumphs.

English Print Culture and the Murder Pamphlet

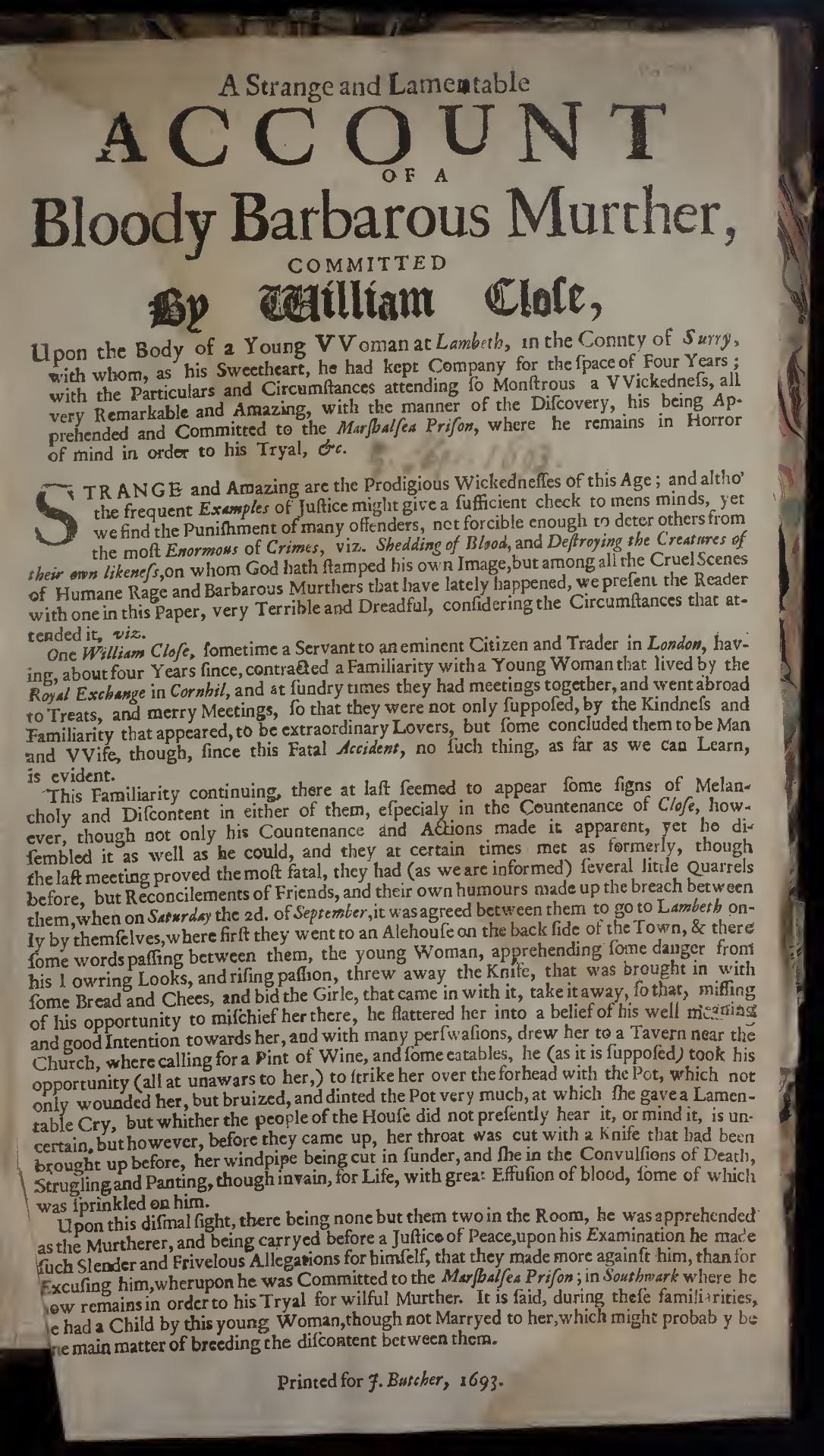

A Strange and Lamentable Account of a Bloody Barbarous Murther (1693 pamphlet)

A Strange and Lamentable Account of a Bloody Barbarous Murther […] (Printed for J. Butcher, 1693), in volume assembled by Narcissus Luttrell, Newberry Library via Internet Archive (public domain), last modified November 12, 2018, online.

In seventeenth century England, a market for popular literature began to emerge as literacy grew in the overall population;10 in this market, the murder story quickly became one of the most widely read genres in print. Before the development of newspapers, print shops (especially in larger urban areas, like London) began distributing cheap booklets with accounts of local crimes, criminal trials, and/or the punishment of the criminals, especially of murderers.11 The first murder pamphlets appeared in the mid sixteenth century, but their popularity in England reached its height in the seventeenth century. Murder pamphlets and broadsides purported to be true accounts of current events, and some may indeed have represented real crimes, trials, and executions; however, these pamphlets often prioritized sensational stories, providing as much entertainment as information.

Like Reynolds’ tales in The Triumphs, most of the murders described in these popular pamphlets were particularly dramatic, scandalous, or gruesome in nature.12 The pamphlets were often composed with evocative language; in the 1693 murder broadside A Strange and Lamentable Account of a Bloody Barbarous Murther, committed by William Close, the author introduced the crime as “so Monstrous a Wickedness, all very remarkable and amazing”. Accounts such as these included details of violence and gore to the point of excess, such as this description of the victim’s death:

“[Her] throat was cut with a Knife that had been brought up before, her windpipe cut in sunder, and she in the Convulsions of Death, Strugling, and Panting, though in vain, for Life, with great Effusion of blood, some of which was sprinkled on him.”

(A Strange and Lamentable Account of a Bloody Barbarous Murther […], printed for J. Butcher, 1693.)

The nature of the crimes in these murder pamphlets was also reliably salacious or shocking. Many pamphlets shared stories of familial murders with unexpected killers and/or victims, like children killing parents or vice versa;13 the pamphlets also disproportionately featured murderous women, like those accused of infanticides and witchcraft.14 Many of the figures involved in these murders were from backgrounds similar to those of the primary readers (that is, from neither the most elite nor the most destitute class),15 the horrific crimes arising from common households and scenarios which were all the more chilling in their familiarity.

Besides their intent to shock and entertain, many authors of murder pamphlets shared Reynolds’ objective of spiritual and moral edification. The murder narratives were often framed as cautionary tales against crime or sin.16 Although not all pamphlets were religiously motivated,17 some Protestant pamphlets adhered to the belief that God would reveal the truth about murders, and often described miraculous events revealing the murderer’s identity18 (see the essay Murther Will Out: Uncovering the Truth for an example). Other murder pamphlets focused on the murderer who had been sentenced to death, including accounts of their gallows speeches in which the murderer reflected remorsefully on the errors that brought them to their end.19

In their overt morality and often indulgent descriptions of violent crimes, murder pamphlets shared many of Reynolds’ priorities in The Triumphs. Although Reynolds’ lengthy and illustrated folio books catered to a print market of higher value, his murder stories were doubtless in dialogue with the demand for crime-related literature that had become so associated with murder pamphlets.

The Overbury Murder Trial

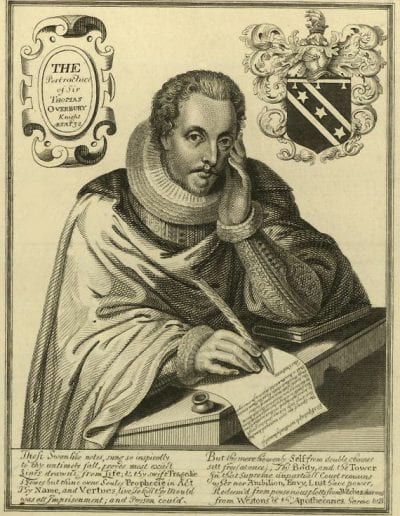

Sir Thomas Overbury (illustration)

Renold Elstracke, Sir Thomas Overbury, engraving, circa 1615-1616, Wikimedia Commons (public domain), last modified March 26, 2015, accessed June 1, 2021. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sir_thomas_overbury.jpg

Robert Carr and Frances Howard, Earl and Countess of Somerset (illustration)

Unknown artist, Robert Carr and Frances Howard, Earl and Countess of Somerset [Contemporary Print in British Museum], circa 18th century, Wikimedia Commons (public domain), last modified June 29, 2020, accessed June 1, 2021, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Portrait_of_Robert_Carr_and_Frances_Howard,_Earl_and_Countess_of_Somerset_(4672416).jpg

Murder stories involving commoners were popular fodder for local pamphleteers, but murder stories involving prominent nobility united a much wider English community in fascination and alarm. In the 1610s (the decade immediately preceding the publication of The Triumphs), the murder of Sir Thomas Overbury and the ensuing trials comprised a true crime scandal that rivaled Reynolds’ tales in complexity and deceit.

The scandal revolved around Robert Carr, first Viscount Rochester and first Earl of Somerset (hereafter referred to as the Earl of Somerset), a favorite of King James I20 and a close personal friend to poet and essayist Sir Thomas Overbury. Conflict arose between the Earl of Somerset and Overbury when the Earl of Somerset began to pursue Frances Howard, who was then married to the Earl of Essex. Frances Howard‘s marriage was soon to be annulled, allowing her to marry the Earl of Somerset in 1613 (hereafter, she is referred to as the Countess of Somerset). Overbury vocally opposed this union, creating a permanent rift between himself and the Earl of Somerset. Perhaps thanks to his adversary’s influence and accusations, Overbury was soon imprisoned to the Tower of London. On September 15, 1613, Overbury was found dead in the Tower, and investigations soon began into the nature of his death.21 In the trials that followed, four associates of the Countess of Somerset were found guilty of poisoning Overbury and sentenced to death; the Earl and Countess of Somerset were widely rumored to have been involved in plotting this murder, as well.22 In 1616, the couple was tried for the murder, found guilty, and sentenced to death. It is possible that King James I never intended to execute the Earl and Countess of Somerset; instead, he imprisoned them in the Tower of London for several years before pardoning and releasing them in 1622.

Published in 1621, only five years after this prominent trial and one year before the subsequent pardoning, the first edition of The Triumphs echoed many themes from the Overbury scandal. Whether or not Reynolds intended to allude to the suspected murderous couple throughout his book, historian J. L. Simmons argued that he may have set all his murder stories in continental Europe to avoid any direct association with Overbury’s murder.23 As Reynolds stated in his Preface:

“I have purposely fetched these Tragicall Histories from forreign parts, because it grieves me to report and relate those that are too frequently committed in our own Country, in respect the misfortune of the dead may perchance either afflict, or scandalize their living friends […]”

(Reynolds, The Triumphs of God’s Revenge, Preface, [2])

English censorship laws may have condemned Reynolds if he was suspected of libelously referencing the English elite in print, which may have compelled him to include this disclaimer.

- Gregory Durston, Crime and Justice in Early Modern England, 1500-1750 (Chichester, West Sussex: Barry Rose Law Publishers, 2004), 174. ↩

- Reynolds, The Triumphs of God’s Revenge, 95. ↩

- According to Joan M. Walmsley in her book, John Reynolds, Merchant of Exeter, and His Contribution to the Literary Scene, 1620-1660 (Lewiston, N.Y.: E. Mellen Press, 1991), 132, “The real source of corruption in the Roman Church which concerns Reynolds lies not so much with the Christians who belong to it as with the Pope, not as an individual, but as an institution.” His criticism for the Jesuits may stem from their perceived role as ambassadors of that institution. ↩

- Reynolds, The Triumphs of God’s Revenge, History XVII, 238. ↩

- Jason Eldred, ““THE JUST WILL PAY FOR THE SINNERS”: English Merchants, the Trade with Spain, and Elizabethan Foreign Policy, 1563—1585,” Journal for Early Modern Cultural Studies 10, no. 1 (2010): 6. ↩

- Robert Cross, “‘The only soveraigne medicine’: Religious Politics and Political Culture in the British-Spanish Match, 1596-1625,” Stuart Marriage Diplomacy: Dynastic Politics in their European Context, 1604-1630, Valentina Caldari and Sara J. Wolfson, eds. (Rochester, NY: Boydell Press, 2018): 68-76. ↩

- Katherine S. Van Eerde, “The Spanish Match through an English Protestant’s Eyes,” Huntington Library Quarterly 32, no. 1 (Nov. 1968): 60-75. ↩

- Berta Cano-Echevarria, “New Directions: Doubles and Falsehoods: The Changeling’s Spanish Undertexts,” in The Changeling: A Critical Reader (Mark Hutchings, ed.) (London: The Arden Shakespeare, 2019): 123. ↩

- Cano-Echevarria, “New Directions: Doubles and Falsehoods,” 124-125. ↩

- Margaret Spufford, Small Books and Pleasant Histories: Popular Fiction and its Readership in Seventeenth-Century England (Athens: The University of Georgia Press, 1981), 19-20. ↩

- Ken MacMillan and Melissa Glass, “Murder and Mutilation in Early-Stuart England: A Case Study in Crime Reporting,” Journal of the Canadian Historical Association (Revue de la Société historique du Canada) 27, no. 2 (2016): 64. ↩

- Ken MacMillan, “True Crime Reporting in Early Modern England,” The Oxford Encyclopedia of Crime, Media, and Popular Culture vol. 3 (Nicole Rafter and Michelle Brown, eds.), (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018): 487. ↩

- “From about 1650, homicidal husbands begin to outnumber murderous wives in the surviving publications, but throughout the period, familial killings remained a common focus, out of all proportion to their actual incidence: in a sample of seventy-seven murder reports published before the 1670s, about half narrate household homicides.” K.J. Kesselring, Making Murder Public: Homicide in Early Modern England, 1480-1680, first edition (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019), 131-132. ↩

- MacMillan, “True Crime Reporting in Early Modern England,” The Oxford Encyclopedia of Crime, Media, and Popular Culture, 486; Kesselring, Making Murder Public, 130-131. ↩

- Kevin Sharpe and Peter Lake (editors), Culture and Politics in Early Stuart England (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1993), 261. ↩

- MacMillan and Glass, “Murder and Mutilation in Early-Stuart England,” Journal of the Canadian Historical Association: 64. ↩

- “The Pamphlets were certainly not an explicitly Protestant, still less a puritan, genre. … Some were written by clergymen (for instance Henry Goodcole, the Ordinary of Newgate Prison, wrote several), but many were not.” Sharpe and Lake (editors), Culture and Politics in Early Stuart England, 258. ↩

- Kesselring, Making Murder Public, 120. ↩

- Ibid, 131. ↩

- “Robert Carr Somerset, earl of.” Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia, 6th edition, March 2021, online. ↩

- Miriam Allen De Ford, The Overbury Affair: The Murder Trial That Rocked the Court of King James I (Buffalo, NY: William S. Hein & Co., 2012), 1. ↩

- “The Overbury Murder Scandal (1615-1616),” in “Early Stuart Libels: an edition of poetry from manuscript sources,” (Alastair Bellany and Andrew McRae, eds.) Early Modern Literary Studies Text Series I (2005), online. ↩

- J. L. Simmons, “Diabolical Realism in Middleton and Rowley’s ‘The Changeling,’” Renaissance Drama (New Series), vol. 11, Tragedy (1980), 157-158. ↩