With Malice Aforethought: The Killer and the Crime

The Killer and the Crime in The Triumphs of God’s Revenge

“Judge, Christian Reader, what simple reasons and trivial motives this inconsiderate Gentlewoman hath for her malice, but she is resolute therein, and as she hath laid the foundation, so she will perfect the edifice of her malice and revenge…”

(Reynolds, The Triumphs of God’s Revenge, History I, 4)

Although Reynolds’ stated intention for The Triumphs of God’s Revenge is the spiritual edification of his readers, the histories also have great entertainment value. With their complex plots, detailed characters, and emotionally charged narration, Reynolds’ stories involve as much drama as one might expect to find in modern works of crime fiction. The descriptions of the elaborate crimes and the characterizations of the murderers responsible for the tragedies are among the most colorful aspects of Reynolds’ book.

Throughout the 30 stories in The Triumphs, 75 characters participate in 57 total murders before suffering mortal consequences for their crimes. Thus, most of the stories involve multiple murders, and the majority of the murders are committed by multiple perpetrators who planned and/or executed the crime(s) together. (Only four of the 30 stories involve one murderer who commits only one homicide while acting alone.) These murders take place under varied circumstances, but the dynamics between the murderers and the motivations for their crimes echo from tale to tale.

Example of Poisoning

Unknown artist, “Ansilva gives Barinthia poyson,” copper engraving, in John Reynolds, The Triumphs of God’s Revenge[…] (London: Printed for R. Gosling, and Sold by J. Osborn, 1726), History VII, 73 (edited excerpt).

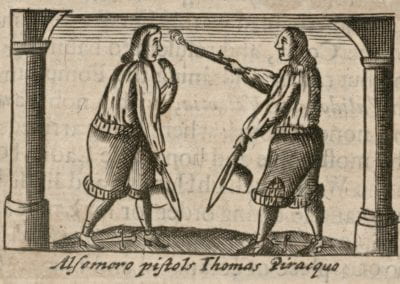

Example of Shooting

Unknown artist, “Alsemero pistols Thomas Piracquo,” copper engraving, in John Reynolds, The Triumphs of God’s Revenge[…] (London: Printed for R. Gosling, and Sold by J. Osborn, 1726), History IV, 33 (edited excerpt).

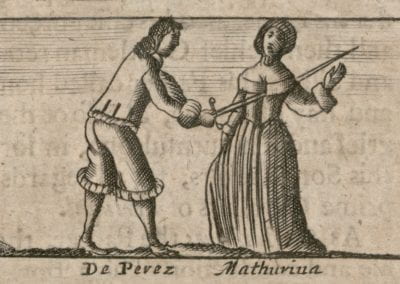

Example of Stabbing

Unknown artist, “De Perez / Mathurina,” copper engraving, in John Reynolds, The Triumphs of God’s Revenge[…] (London: Printed for R. Gosling, and Sold by J. Osborn, 1726), History XVI, 217 (edited excerpt).

Example of Man Throwing Woman down a Well

Unknown artist, “Christina / Mauris throws her into the well,” copper engraving, in John Reynolds, The Triumphs of God’s Revenge[…] (London: Printed for R. Gosling, and Sold by J. Osborn, 1726), History XV, 200 (edited excerpt).

Example of an Accomplice

Unknown artist, “Blancheville gives le Valley gould to pistol his Master,” copper engraving, in John Reynolds, The Triumphs of God’s Revenge[…] (London: Printed for R. Gosling, and Sold by J. Osborn, 1726), History XIX, 268 (edited excerpt).

In each history, at least one character can be considered the “primary murderer”, or the character who initially conceives of a plan to kill another character (or more). Some primary murderers act alone, but many plan their murder(s) with a co-conspirator or instruct subordinate accomplices to execute their plan. Many come from wealthy or privileged families and have access to the resources and manpower to develop covert and, occasionally, elaborate plans to commit murder. Whether these characters physically participate in the crime or not, Reynolds emphasizes the culpability and moral reprehensibility of the primary murderers for setting the devilish crime in motion. Throughout The Triumphs, the role of the primary murderer is performed by female characters nearly as often as by male characters: of the 48 total “primary” murderers, 26 are men, and 22 are women.

The murders are frequently committed with assistance from accomplices, or characters who were paid or influenced by the primary murderer to perform the crime. Most of these accomplices (23 of the total 27) are men, and many are “apothecaries” or “physicks” that provide poison to be used in the murder. The four female accomplices are subservient to the primary murderer, either servants or lovers, and are compensated or otherwise coerced to participate in the crime on the primary murderer’s instruction.

Murderers take many forms throughout Reynolds’ histories: dissatisfied husbands, envious sisters, ungrateful sons, vengeful widows, and many more. Although some murders are motivated by unadulterated greed, jealousy, or hatred, the majority of the murderers plotted their crimes as a response to one common conflict: romance gone wrong. Competition for suitors or the desire for extramarital romances led many men and women to eliminate their obstacles; parents disapproving of their sons’ or daughters’ romantic choices or controlling their marital activity often precipitated deadly violence. Reynolds explicitly condemns the immorality of lustful and extramarital relationships by demonstrating their disastrous consequences, but the complexity and scandalous nature of these romances doubtless appealed to early modern readers, as well.

Poisoning is the most common method of murder throughout The Triumphs, often chosen for its ability to evade immediate identification as homicide. Many other fatalities are caused by stabbing with a knife or rapier, shooting with a pistol, or a combination of these violent acts. Less frequent murder methods include strangulation, smothering, throat slitting, and even pushing a victim down a well. See the table for the full list and frequency of murder methods.

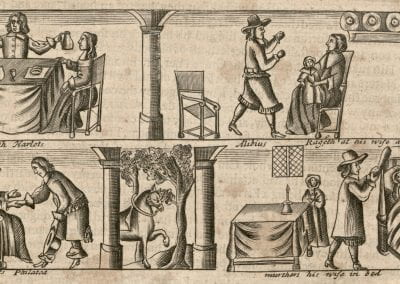

Example of a Male Murderer

Unknown artist, “Alibius with Harlots / Alibius Rageth at his wife and babe / Alibius courts Philatea / murthers his wife in bed,” copper engraving, in John Reynolds, The Triumphs of God’s Revenge[…] (London: Printed for R. Gosling, and Sold by J. Osborn, 1726), History V, 45 (edited excerpt).

Reynolds takes pains to condemn the character and actions of each murderer, particularly the primary murderers who conceived of the crime. However, his description of his characters’ moral susceptibility often diverges along a gendered line. For many male murderers, Reynolds describes a progression of sinful behavior that begin with minor transgressions and eventually leads to “the scarlet sin” of murder. In History V, Alibius grows unhappy in his marriage, and he succumbs to the following series of sins before reaching his lowest moral threshold and murdering his wife:

“[For] now he begins to love swearing, whoredom, and drunkenness, that before he hated; and to hate the Gospel of Christ, and the professors thereof, that before he loved; a most wretched exchange, where we take from our Souls to give our senses; and a woeful bargain, where we sell God to buy the Devil.”

(Reynolds, The Triumphs of God’s Revenge, History V, 46)

Some female murderers also succumb to sins like lust before becoming killers, but Reynolds emphasizes that women are far more susceptible to sinful, wicked behavior than men. In many histories, male sinfulness, like that of Alibius, is presented as a tragic downfall, but female sinfulness is often described as the realization of an innate inclination:

“The effects of malice and revenge in men are finite, in women infinite; theirs may have bounds and ends, but these none, or at least, seldom and difficultly: for having once conceived these two monsters in their fantasies and brains, they long till they are delivered and disburthened of them […]”

(Reynolds, The Triumphs of God’s Revenge, History XI, 147)

Throughout The Triumphs, male primary murderers slightly outnumber female primary murderers, but women are often characterized as more wicked, and their descent into sin more dangerous.

The Killer and the Crime in Early Modern England

Although researchers have noted an overall decrease in English homicide rates in the centuries following the medieval period, a slight increase in violence and homicides occurred at the end of the sixteenth century and beginning of the seventeenth, especially in public spaces.1 If the public was aware of this era’s increased violence, Reynolds may have written The Triumphs of God’s Revenge in response to a rising interest in crime during this era. However, his murder stories appear to be dramatic distortions of real homicides in early modern England. Recent assessments of English assize court records and coroners’ inquisitions between 1480 and 1680 indicated that many homicides resulted from unplanned acts of violence, occurring in “drunken brawls, workplace disputes, and sudden angry responses to a slight of some sort.”2 Such non-domestic murders were usually public, occurring with witnesses and without the secrecy, planning, or accomplices that Reynolds describes in his histories. In domestic murders (or murders involving spouses, family members, or servants), the dynamics between the killer and the victim typically reflected the power dynamics of the home: the male heads of household typically killed their wives and servants more frequently than the reverse.3 On a whole, the gender of the typical murderer reflected this power dynamic. According to virtually all studies of homicides in Elizabethan and Stuart England, the vast majority of individuals accused of –and convicted of –murder and manslaughter were men.4 In the early seventeenth century, a higher-than-average number of women were accused of infanticide or murder via witchcraft, but these accusations and convictions nevertheless account for a minority of overall murder cases.5 Throughout The Triumphs of God’s Revenge, Reynolds only includes one instance of infanticide by a woman (in History XXVIII) and did not explicitly describe any women as practicing witchcraft; instead, he writes about a disproportionately high number of women who plotted murders against their husbands, suitors, and siblings.

Because many murders in early modern England were unplanned, the most common murder weapons appeared to have been readily available tools and objects. Household knives, swords, blunt objects, and even farming implements were among the most frequently used weapons in lethal confrontations. Firearms were first used in murders in the late sixteenth century, and their use in lethal violence gradually increased as firearm ownership increased. In perhaps the starkest contrast to the murders in The Triumphs, less than two percent of reported murders were caused by poison during this era.[6. Ibid, 15-16.]

The Unique Status of Duels

Example of a Duel

Unknown artist, “Grand Pre Kills De Malleray in a Duell,” copper engraving, in John Reynolds, The Triumphs of God’s Revenge […] (London: Printed for R. Gosling, and Sold by J. Osborn, 1726), History I, 1 (edited excerpt).

Reynolds often includes duels in his histories; in these duels, two male characters attempt to resolve a private conflict by fighting to the death with either swords or pistols. The dueling men each bring seconds, or men to finish the fight in the event of a fatality, and “chirurgeons,” or medical professionals to aid or evaluate the physical state of the fighter. Throughout The Triumphs of God’s Revenge, Reynolds frequently describes killings in duels as different legal infractions than cold-blooded murders, perhaps due to the fighters’ mutual agreement preceding each duel (often explicitly stated in letters between these men, which Reynolds includes in the histories). Several of the characters who kill their opponents in a duel are tried in court and pardoned, whereas virtually no other murderer is released without punishment by the end of their history. Occasionally, Reynolds differentiates between the legal ruling and the divine consequences of a death in a duel, particularly when such a death involves a dishonorable or treacherous maneuver in the fight:

“So this murther of his is remitted in Earth, but I fear me, will not be forgotten in Heaven: for though men be inconstant in their decrees, yet God will be firm and upright, as well in the distribution, as execution of his judgment.”

(Reynolds, The Triumphs of God’s Revenge, History XI, 145)

Reynolds’ complicated treatment of duels reflects the murky legal status and official treatment of duels during this era. In 1609, Chief Justice Sir Edward Coke stated that duels were considered illegal by the English crown and individuals who killed their opponent(s) in duels could face charges of murder or manslaughter.6 Although some duelers suffered penalties – including capital punishment – under English law, the treatment of duels and individual duelers appears to have varied widely in the early seventeenth– century courts, and many parliamentary attempts to discourage duels in England appear to have been ineffective.7 A duel was considered a crime against the crown, but it was a crime almost exclusively committed by landed men of a distinguished class, and may have been penalized less harshly due to the status of the accused. In the eyes of elite members of parliament, a duel may have been perceived as “an activity engaged in by men of their own sort and perhaps sometimes excusable as a foible of the man of honour or military breeding.”8 As is frequently the case in The Triumphs, the well-to-do and powerful men who engage in duels often walked free for their crimes.

- Randolph Roth, “Homicide in Early Modern England 1549-1800: The Need for a Quantitative Synthesis,” Crime, Histoire & Sociétés / Crime, History & Societies 5, no. 2 (2001): 47. ↩

- K.J. Kesselring, Making Murder Public: Homicide in Early Modern England, 1480-1680, first edition (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019), 17. ↩

- Roth, “Homicide in Early Modern England,” 47; Kesselring, Making Murder Public, 15. ↩

- J. M. Beattie, Crime and the Courts in England, 1660-1800 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1986), p. 97; Kesselring, Making Murder Public, 14-15. ↩

- Kesselring, Making Murder Public, 14-15. ↩

- Ibid, 95. ↩

- Joan M. Walmsley, John Reynolds, Merchant of Exeter, and his Contribution to the Literary Scene, 1620-1660 (Lewiston: The Edwin Mellen Press, 1991), 85. ↩

- Kesselring, Making Murder Public, 115. ↩