Thy Christian Friend: John Reynolds and His 30 Murder Stories

Biography of John Reynolds

John Reynolds, the author of The Triumphs of God’s Revenge, left behind limited information on his life. He was born around 1588 in Exeter, UK; as a young man, he followed in his father’s footsteps and became a merchant. At an unknown date before his first marriage, Reynolds’ mercantile work took him to France. He spoke French fluently and it is believed that he also had knowledge of other European languages, possibly learned through interactions with people from the countries that feature in The Triumphs.

Although many of the histories in The Triumphs took place in Catholic-majority countries in continental Europe, his writings suggest that Reynolds held strong Reformed Protestant beliefs. In 1624, he anonymously published two politically charged pamphlets stemming from those beliefs; these pamphlets offended King James I, leading to Reynolds’ extradition from France and imprisonment in England. In 1626, while possibly still serving his sentence, he married his first wife.1 He was released from prison at an unknown date and moved back to Exeter, where he had a family and career. The historical record indicates that he married once more after his first wife passed away, but his life after 1655 remains a mystery.2 Not even a confirmed portrait of Reynolds exists today.

Bibliography of John Reynolds

Triumphs of God’s Revenge Title Page

John Reynolds, The Triumphs of God’s Revenge against the Crying and Execrable Sin of Willful and Premeditated Murther […] (London: Printed for R. Gosling, and Sold by J. Osborn, 1726), title page.

According to the English Short Title Catalogue, Reynolds’ works comprised 50 printed editions from the years 1621 to 1778. However, this number was made up of only four distinct titles: The Triumph’s of God’s Revenge; Vox Coeli, or, Newes from Heaven; The Flower of Fidelitie; and Votivæ Angliæ: or, The Desires and Wishes of England.3

The Triumphs of God’s Revenge was the first of titles and by far the most popular, establishing Reynolds as a successful author. It was published in a total of 26 editions (including excerpts and abridgments) in the 157 years following its first appearance. In 1621, Reynolds published the first edition of The Triumphs of God’s Revenge as a collection of only five tales (called histories); perhaps responding to the book’s popularity, he added twenty-five new histories to the 1635 edition, and each subsequent edition included these thirty total histories (including the 1726 edition in the Pritzker Legal Research Center’s collection).

Of the 26 editions of The Triumphs, at least half were printed as folios, or large, display copies. Books of this size were more expensive than smaller editions such as octavos and duodecimos. Small formats only made up a small fraction of the editions printed of The Triumphs, suggesting that this title was a valued possession.4

Reynolds’ other literary works belonged to different genres. Vox Coeli, or, Newes from Heaven was a controversial political pamphlet condemning the Spanish Match, a possible engagement that would have united Protestant-majority England with Catholic Spain (see our essay “In These Our Days: Cultural Context for The Triumphs“ for more information). Votivæ Angliæ: or, The Desires and Wishes of England was also a political pamphlet, this time advocating for the restoration of the Palatinate to Protestant rule. Reynolds’ final major literary work, The Flower of Fidelitie, was a romance and, unlike his anonymous political works, its full title included the phrase “By John Reynolds, of Exon merchant, author of that excellent history, entituled [sic], Gods revenge against murther,” testifying to the success of the volume discussed here.5

“Against the Snares and Enticements of the Devil”: The Origins and Purposes of The Triumphs of God’s Revenge

Each of the thirty histories in The Triumphs of God’s Revenge followed a basic narrative structure of sin and retribution. Devilish temptations like lust and the desire for revenge always led at least one character to commit murder; later, divine intervention always led to the discovery of the truth about the crimes and the punishment of the guilty. Although The Triumphs of God’s Revenge was often sold alongside other works of prose or leisurely reading 6 and may have appealed to readers for its entertainment value, Reynolds intended his histories to be cautionary tales promoting Protestant values. In “The Author His Preface to the Reader,” Reynolds instructs his Christian audience to follow the examples in his stories and thus avoid a sinful life:

“My intent, desire, and prayer, is, that if thou art strong in Christ, perusing and reading of these Histories may confirm thy faith, and the defiance of all sins in general, and of Murther in particular; or if thou art but weak in the rules of Christian fortitude and piety, that hereby it may encourage and arm thee against the allurements of the world, and the Flesh; but especially against the snares and enticements of the Devil, which may stir thee up either to Wrath, Despair, Revenge, or Murther: that by the contemplation thereof, thou maist resemble the Bee and not the Spider, and so draw Hony from all flowers, but poyson from none.”

(Reynolds, The Triumphs of God’s Revenge, Preface, 4)

Instead of merely condemning the villains, Reynolds expected his readers to identify with the moral susceptibility of the characters in the story, including the murderers. The stories demonstrated that any Christian could be corrupted by the devil, and could commit sins as grave as murder; indeed, any Christian reader could suffer the same fate as the stories’ villains if they also abandoned their religious virtues and practices for sin.

The historicity of these cautionary tales has been a matter of debate. Earlier in the Preface, Reynolds discussed the origins of his histories, claiming to have collected them from his time living on the Continent:

“I must further advertise thee, that I have purposely fetched these Tragical Histories from forreign parts […] For mine own part, I have illustrated and polished these Histories, yet not framed them according to the Model of mine own fancies, but of their passions, who have represented and personated them: and therefore if in some places they seem too amorous, or in others too bloody, I must justly retort the imperfection thereof on them, and not they self on me; sith I only represent what they have acted, and gave that to the publick which they obscurely perpetrated in private.”

(Reynolds, The Triumphs of God’s Revenge, Preface, 3-4)

Here he stressed the veracity of the tales in the book, portraying himself as their unopinionated messenger and denying any personal responsibility or authorship of the objectionable content therein. He later contradicted himself, claiming to have taken more of an editorial role in their composition: “I found out the grounds of them in my Travels, and (at mine owne leisure) composed and penned them, according to the rule of my weake Fancie and Capacity….” (Reynolds, The Triumphs of God’s Revenge, The Author his Re-Advertisement to the Judicious Christian Reader, B.) Whether or not he modified his source material, Reynolds maintained that the contents of his book reflected actual events from continental Europe. Modern scholars have refuted this claim and now regard the histories in The Triumphs of God’s Revenge strictly as works of fiction.7 Reynolds may have included his adamant truth claims to amplify the emotional response to the histories, or to add real-life relevance to the divine and legal punishments for sins like murder.

“Thirty Several Tragical Histories” in Brief

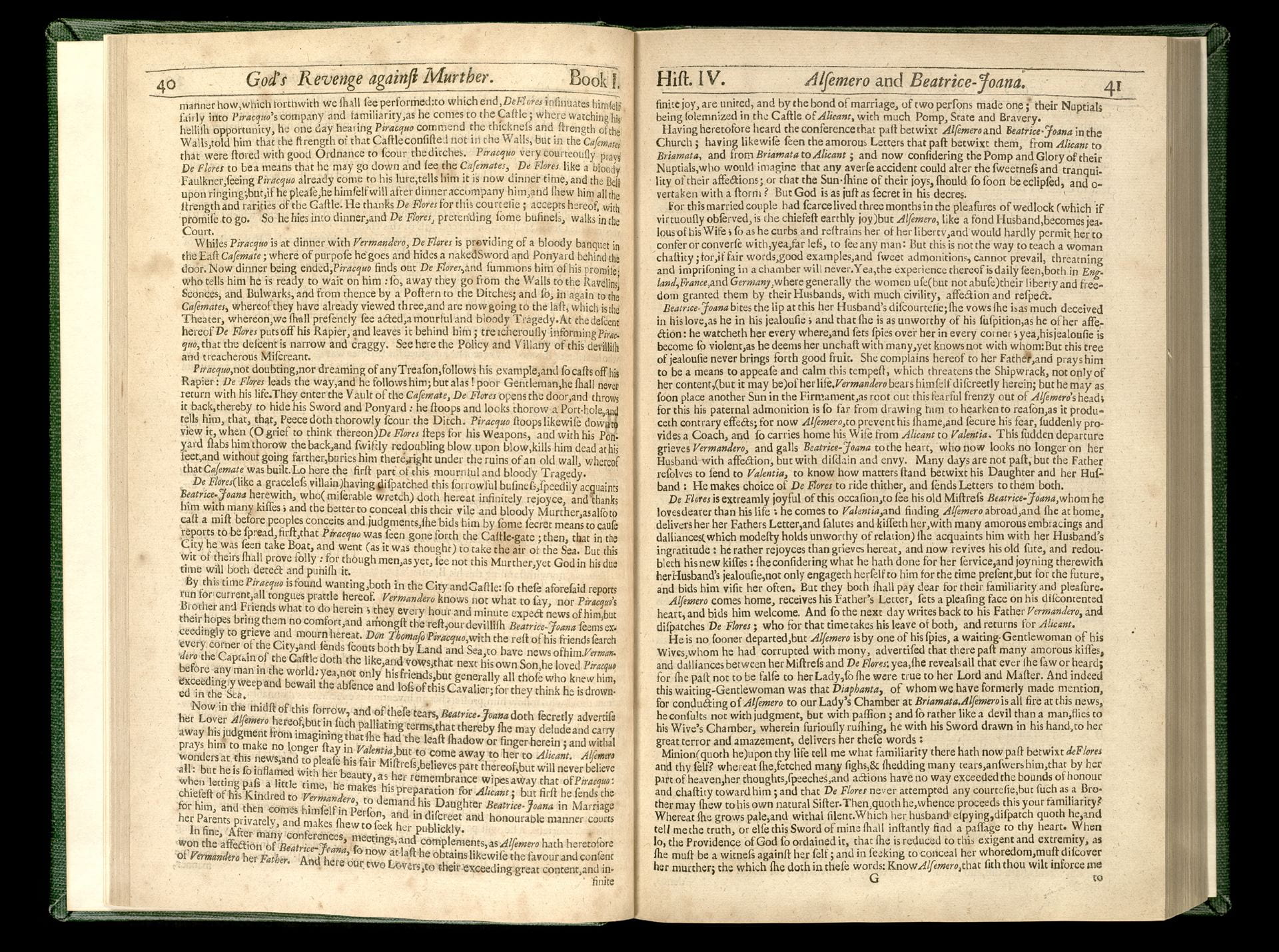

Every history in The Triumphs of God’s Revenge is preceded by an illustration depicting major events from the story and a short, written summary of the tale (these summaries were also printed in the book’s table of contents). The illustrations are copper engravings created by one or more unknown artists, each comprising a series of captioned vignettes, usually read left-to-right and top-to-bottom, similar to the reading conventions of contemporary comic strips. Evocative and easily comprehensible, these visual and verbal introductions present the major themes recurring throughout The Triumphs of God’s Revenge and invite the reader to learn more. Click here to view all of these illustrations and read all of the summaries in order.

(Note: Pritzker Legal Research Center’s 1726 edition of The Triumphs of God’s Revenge includes a printing error in which pages 421-430 are missing, including the introductory illustration and summary of History XXVIII. These 29 scans represent the 29 total illustrations and summaries included in the library’s copy. Please note that each scan has been cropped and edited to improve the legibility of the text and images.)

History IV: Alsemero and Beatrice-Joana

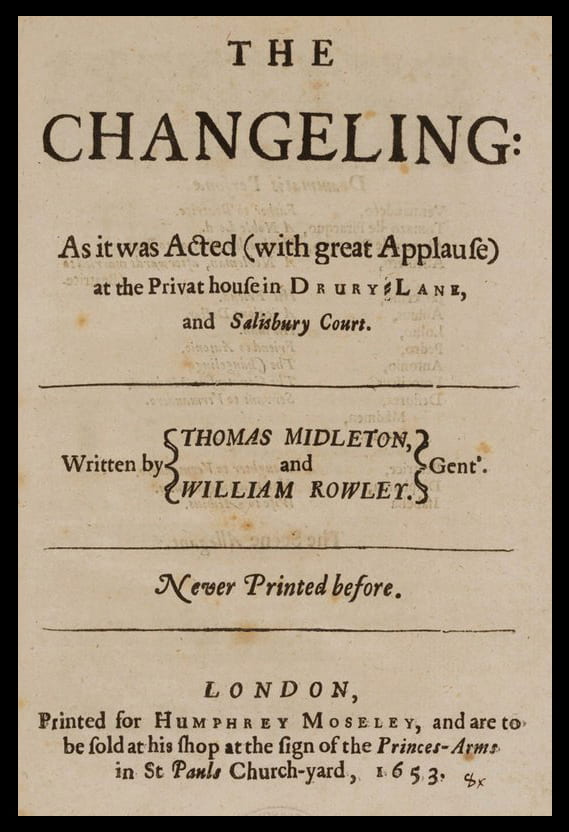

Beyond its many decades of popularity among early modern English readers, The Triumphs of God’s Revenge influenced the creation of new literary and theatrical work. Most notably, playwrights Thomas Middleton and William Rowley wrote The Changeling as early as 1621, deriving much of its plot and characters from The Triumphs of God’s Revenge.8 In the play, Middleton and Rowley reinterpret the complex and sordid plot of History IV; both The Changeling and History IV revolved around themes of female treachery and violence in ill-fated romances. The Changeling became a popular court performance in 1623-16249 and appeared frequently on English stages throughout the seventeenth century, its popularity perhaps intertwined with the consistently high readership of The Triumphs during this era.

As the basis for Middleton and Rowley’s play The Changeling, Reynolds’ tale of Alsemero and Beatrice-Joana captured the imagination of generations of readers and stage audiences. In its literary form, Reynolds’ emotional prose in History IV reflects the urgency of his spiritual message throughout The Triumphs of God’s Revenge. Click here to read this full history from the 1726 edition.

The Changeling

The Changeling (play), (London: Printed for Humphrey Moseley, 1653), title page, Wikimedia Commons (public domain), last modified December 20, 2020, online.

- Joan M. Walmsley, John Reynolds, Merchant of Exeter, and His Contribution to the Literary Scene, 1620-1660 (Lewiston, N.Y.: E. Mellen Press, 1991), 20. ↩

- K. Grudzien Baston, “Reynolds, John (b. c. 1588, d. after 1655), merchant and writer,” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, https://doi-org.turing.library.northwestern.edu/10.1093/ref:odnb/23422. ↩

- Regarding the four titles mentioned here, they include abridgments and later variations of the same work. The letters have been transcribed to conform to current English.Reynolds may or may not have written a fifth title, the 1606 poem, Dolarnys Primerose, Or the First Part of the Passionate Hermit. It is commonly attributed to our John Reynolds, but the ESTC notes an attribution to a different, though contemporary, man of the same name (English Short Title Catalogue, accessed July 20, 2021, English Short Title Catalogue – Welcome (bl.uk)). Furthermore, the DNB suggests a possible sixth title, as well: “His Apologie of the Reformed Churches of France (1628) was written as if by a French author but it is probably his own work; Reynolds may have wished to avoid annoying the new king.” (Baston, “Reynolds, John,” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.) If this was an original work, and not a translation, this pretense would echo his earlier claims about The Triumphs. ↩

- Walmsley, John Reynolds, 32. ↩

- See Walmsley, John Reynolds, 5. Walmsley states that The Flower of Fidelitie was an early work of Reynolds’ that was only published much later in his life, likely further attesting to the success of The Triumphs of God’s Revenge. ↩

- Jules Paul Seigel, “Puritan Light Reading,” The New England Quarterly 37, no. 2 (June 1964): 191. ↩

- Baston, “Reynolds, John,” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. ↩

- Jerry H. Bryant, “John Reynolds of Exeter and his Canon,” The Library s5-XV, issue 2 (June 1960): 107. ↩

- Mark Hutchings (editor), The Changeling: A Critical Reader (London: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc., 2019), xv. ↩