|By Megan Hazlett|

Introduction

While my move to Chicago was filled with excitement, it was also met with some caution. As a native Floridian, I was warned of the intense winters, and feared not only being frozen by the cold, but also enduring excessive hours of darkness. According to Psychology Today, an estimated 10 million people suffer from seasonal affective disorder (SAD) every year. Defined as depression that surfaces during the same season each year, SAD is seen in most during the winter months. SAD affects various aspects of life, including appetite, social inclinations, and sleep patterns. As someone unfamiliar with seasonal swings, this got me thinking about how they could affect other aspects of my life beyond what is usually reported by health professionals.

Particularly, it got me wondering how SAD could influence something very close to my heart: music. I began to think about how my music listening habits may be altered by SAD and other seasonal trends. Would I need more variety in my music to cope during the winter months? Would I listen to more angsty music during January and February than I would normally listen to in the summer? While I continue to monitor my own behaviors, I thought it could be interesting to see if I could detect certain seasonal music listening habits on a population level.

For this project, I decided to focus on two particular questions regarding seasonal effects and music listening habits:

(1) Does the quantity of unique songs we listen to differ by season (i.e. do we need more variety in our music depending on the season)?

(2) Do the seasons effect what genre of music we listen to?

Initial Research

While there is limited existing research about the relationship between consumption of music and the seasons, there is plenty of evidence about which times of the year are the most hectic for music events. Most of top 20 music festivals, such as Coachella and Lallapaloosa, are scheduled for Spring or Summer, and none of the top 20 are scheduled Winter. According to MusicConsultant.com, the best time for artists to release new music is between January and February, and between April and October, suggesting that songs released in Winter will not do well because of holiday chaos, and songs released in March will be overshadowed by the famous South by Southwest festival.

As far a research about the relationship between the seasons and music genre, a study conducted by psychologist Terry Pettijohn and collaborators caught my eye. According to their research, there does seem to be some relationship between genre preference and season. Pettijohn built his research on a previous study about daylight savings time, which found that with any environmental threat, such as a change in routine caused by waking up an hour earlier, people prefer to consume more meaningful content, i.e. slower, longer, more comforting and romantic music. Basically, music in trying times are used as coping mechanisms. In his study, Pettijohn primed United States college students in the Northeast and Southeast to report their music preferences in the different seasons. Based on what the students reported, he noticed that all students seem to prefer more relaxed music, such as jazz, folk, and classical, in the fall and winter, but more uplifting music, such as electronic and hip hop, in the summer. I thought this study was very interesting, however, was cautious about the results because of the self-reported nature of the study.

Hypotheses

Based on this initial research, I developed two hypotheses to test my questions.

* First, I expect there to be a greater quantity of unique songs consumed in the Spring and Summer. This is due to not only to festival lineup in these months, but also the recommendation by MusicConsultant.com to avoid releasing music in the winter.

* Second, I expect that there will be a seasonal effect on genre. Particularly, I believe I will see a preference for pop in the Summer and Spring months, and a preference in rock, soul, and angst (emo, punk, grunge) in the Fall and Winter. I believe this, based not only because of the seasonal study by Pettijohn, but also because of the previous research about using music as a coping mechanism.

Data Sets

For this study, I used the following data sets.

The first is Billboard Hot 100, which reports the top 100 hits for every week from August 2, 1958 to June 22, 2019 in the United States. The original data set consists of 317,795 entries with 10 columns of information. The columns provide information on the WeekID (assigned by Billboard), the current rank (1-100) of a particular song during that week, the song name, artist name, songID (a unique indicator of the song consisting of the song and artist name), how many times the song was charted, the song’s rank in the previous week, the peak rank of the song, and how many weeks the song stayed in the top 100. For the purpose of this study, I only used the three columns: WeekID, SongID, and current rank.

The second data set is Million Song, which is contains genre information about artists. The original data set contains a million rows of information about a given song, including information about the song genre, song duration, tempo, time signature, number of beats, energy and much more. While there were originally 46 columns of information, I was only interested in finding a song’s genre, or genres, since this information was not provided by the Billboard Hot 100 dataset. I wanted to be able to add genre information to detect genre popularity within seasons.

Part I: Determining Relationship Between Quantity of Music Variety (Number of Unique Songs) and the Seasons

To determine if there is a relationship between the seasons and music variety, I used only Billboard Hot 100 data set. This data set was aggregated to show the unique number of hits per month (the number of charted songs per month), which I used to represent the variety of songs consumed by the public each month.

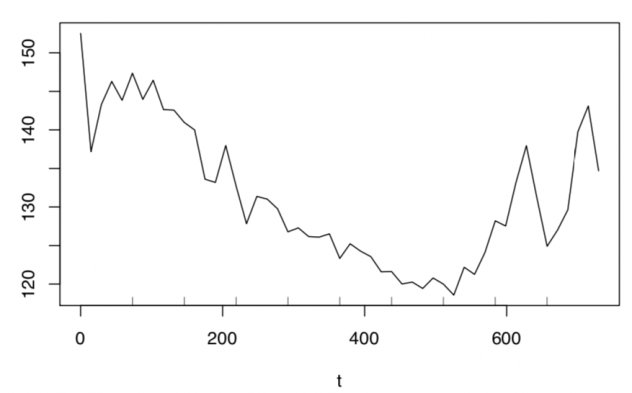

From this aggregated data set, I created four plots to graphically assess the number of hits per month by looking at the elements of time series decomposition (Figure 1). The first plot in Figure 1 draws the number of hits over time. We see from this graph that there is certainly a trend over time, with a dip in the number of hits per month in the late 1990s. We also notice from this plot lots of variation in the number of hits, which could indicate the presence of a seasonal trend. I dove deeper with the seasonal trend plot, which showed a consistent wiggle, indicating the possibility of seasonality. The third plot shows the cyclical trend of the number of hits per month. Based on the plot, there does not seem to be a large cyclical presence in the data, except for a dip and rise in the late 1990s. Finally, the last plot in Figure 1 explored the random aspect of the data. We see from the plot that randomness could play a great deal in the temporal relationships of the data. Based on the second plot, I decided to further explore the seasonal effect on number of hits of per month.

I used a bar graph (Figure 2) to compare the average number of hits per month. The bars seem to be at an even height, indicating that the average number of hits per month may not differ by month.

Finally, in Figure 3, we look at the average number of hits per month by season (Winter = [December, January, February], Spring = [March, April May], Summer = [June, July, August], Fall = [September, October, November]). From Figure 3, the number of hits does not seem to vary with the seasons because the bars are approximately the same height.

To address the conflicting theories from the time series decomposition and bar graphs, I employed Poisson regression to analytically assess the presence (or lack of presence) of a seasonal effect on number of hits per month. My inspiration to use this method came from a student project about determining if there is a seasonal effect in number of suicides.

I used the Poisson model

![]() where µ is the Poisson incident rate and where

where µ is the Poisson incident rate and where

To represent seasonality as a predictor, I used the following two models:

(1) Using properties of sine and cosine to emulate seasonality

![]() (2) Using the season itself as a factor

(2) Using the season itself as a factor

Running the first model, we see that while the chi-squared test of overall significance indicates that the model is statistically different than the null model, time itself is the only significant predictor of number of hits. Thus, the sine and cosine variables used to represent season are not significant predictors, and season is not a driving force is predicting the number of hits per month.

I verified this conclusion with model 2, which revealed that none of the seasons are significant predictors of number of hits.

To finalize the results, I compared the Poisson model 2 with a random forest model of the same structure. I used 500 trees, which I verified was appropriate in Figure 4, and sample 3 variables for each split. From Figure 5 we see that season does not appear to be an important variable in predicting number of hits. Finally, from the partial dependence plots in Figures 6.1, 6.2, and 6.3, it is confirmed that season is not influential in predicting the number of hits. These conclusions align with what was found with the Poisson models.

In conclusion, based on the Billboard Hot 100 data, we see from both graphs and the results of the models, that there does not seem to be a seasonal effect driving the number of hits, and thus unique songs consumed, per month. While this does not support my hypothesis, I take these results with caution. The Billboard Hot 100 data set has a bias to only represent people who listen to popular music. In addition, my initial assumption that number of unique hits per month can represent number of unique songs listened to on a population level, may not actually capture this variable.

Part II: Determining Relationship Between Music Genre and the Seasons

To tackle the question of whether or not seasonality affects the genre of music we listen to, I merged the Million Song data set with the Billboard data set to get information about song genre. For the sake of this study I only used Billboard Hot 100 songs with a genre mapped from Million Song (35% of the Billboard set do not have a genre). Note that many songs have more than one genre listed and thus those songs are duplicated on the list for every genre listed.

First, for some initial exploratory data analysis, I determined the top genres in the merged data set (Figure 7). As expected: pop, rock, and soul top the charts.

Next, I wondered if the popularity of the top three genres are affected by season. In Figures 8, 9, and 10, we look at the number of hits per season from 1958-2019, for pop, rock, and soul individually.

There does seem to be some sort of temporal trend based on the periodic peaks in number of hits, but the trends do not seem related to season. This becomes even more apparent in Figures 11, 12, and 13 when we look at the total number of hits by genre per season. There appears to be virtually no difference between number of hits between seasons. However, this could be due to the scalability of the graphs, so I decided to further investigate with a statistical test.

I ran one-way ANOVA tests on pop, rock, and soul subsets to determine if there is a difference in the observed mean of hits by season and the means expected under the null hypothesis H0 = µ1 = µ2 = µ3 = µ4

and the alternative that at least one of the means is not equal. From the ANOVA tests we see that for pop, rock, and soul there appears to be no seasonal difference. Thus, based on both the plots shown in Figures 11, 12, and 13, and the supporting ANOVA tests, we conclude there to be no seasonal difference in the type of music people consume. The tests for pop, rock, and soul all result in p-values greater than 0.8. Thus, the initial hypothesis that there is a seasonal difference between when pop, rock, and soul are consumed is not supported.

Lastly, I was curious to see if a seasonal effect is present particularly in “angsty music”, which has a reputation for exploring sadness and depression. I defined “angsty music” to be genres that included the words “emo”, “metal”, “pop punk”, or “grunge”. Following the same procedure as before, I created Figures 17 and 18 of hits over time and hits by season. Again, there appeared to not be much of a difference except for a dip in summer. When I ran the one-way ANOVA test to determine statistical difference between the means of season, again we see that there is no difference between angsty music popularity by season, with a p-value of 0.886.

In summary, contrary to my hypothesis, the ANOVA tests and graphs imply that there does not seem to be a seasonal effect on genre of music.

Conclusions, Final Remarks, and Future Directions

While the results of this analysis are not what I expected, I did learn something valuable from this study: you like what you like when it comes to music and you consume it consistently, no matter the season. It doesn’t matter if it’s summer or winter, if someone loves rock music, they’re going to listen to it consistently throughout the year. Although SAD does not play the role that I hypothesized it would in music listening habits, I find comfort in the fact that our favorite genres of music get us through all the seasons. And that’s exactly how I survived my first Chicago winter.

This study answered many of my questions about how SAD affects music listening habits, but I would be interested in further exploring this topic in the following ways. (1) Studying those actually diagnosed with SAD to determine the true effect of the disorder on music listening habits. (2) Using musical elements (such as chord progression and lyrics), rather than genre, to assess seasonal trends. This could capture more nuanced behavior in how our musical taste changes with the seasons.

Code

Code for this project can be found on github.

References

Goetz, R. (2019, October 9). When is the Best Time of Year to Release an Album or EP? Retrieved April 8, 2020, from https://musicconsultant.com/music-career/when-is-the-best-time-of-year-to-release-an-album-or-ep/#.XoYPndNKiL8

Mehta, V. (2017, November 1). When Seasons Change, So Do Musical Preferences, Says Science. Retrieved April 8, 2020, from https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/head-games/201711/when-seasons-change-so-do-musical-preferences-says-science

Miller, S. (2020, January 6). Billboard Hot weekly charts – dataset by kcmillersean. Retrieved April 8, 2020, from https://data.world/kcmillersean/billboard-hot-100-1958-2017

Ellis, D. P. W., Lamere, P., & Whitman, B. (2011). Million Song Dataset. Retrieved April 8, 2020, from http://millionsongdataset.com/

Psychology Today. (2019, February 7). Seasonal Affective Disorder. Retrieved April 8, 2020, from https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/conditions/seasonal-affective-disorder

Stack Exchange. (2015). Is this an appropriate method to test for seasonal effects in suicide count data? Retrieved April 8, 2020, from https://stats.stackexchange.com/questions/144745/is-this-an-appropriate-method-to-test-for-seasonal-effects-in-suicide-count-data

Writers, F. (2020, February 12). TOP 20: Music Festivals in the USA 2020 – Festicket Magazine. Retrieved April 8, 2020, from https://www.festicket.com/magazine/discover/top-festivals-usa/