The University in Wartime

At first the Northwestern community, like many others, had a rather romantic attitude towards World War I until news reports on the realities of war spread across campus. Yet, as more and more students and faculty mourned the deaths of friends and colleagues who lost their lives on European battlefields, a willingness to serve their country remained strong.

Women on the Homefront

During World War I, the men conscripted from the civilian work force had to be replaced by women, whose contributions to factory work and other military and domestic support roles kept spirits afloat at home and on the battlefield. In the University community, those who couldn’t ship out as nurses found other ways to contribute to the national effort.

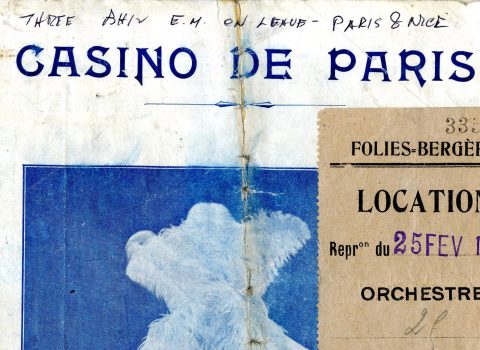

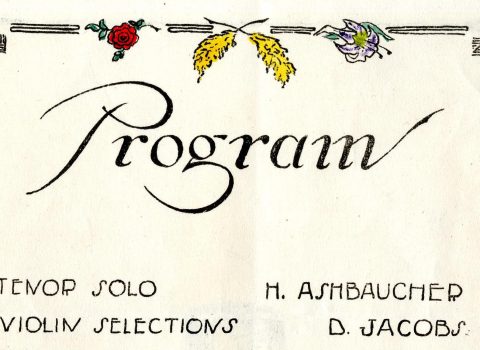

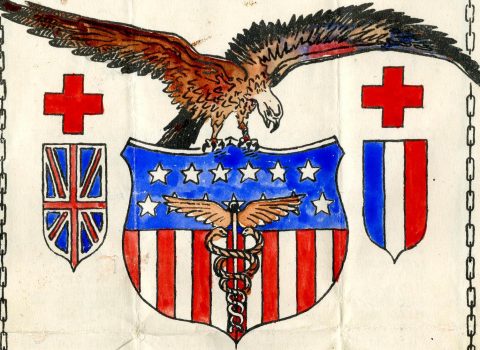

Student scrapbook, 1917-18

Edith Sternfeld entered Northwestern in 1917 and, like many other students at that time, documented her college life in a scrapbook. This scrapbook serves as a vivid record of student life during the Great War, typifying the response of other college women across the United States. Tags, lapel pins, and buttons reflect Sternfeld’s participation in fundraising activities to purchase war bonds, support American soldiers and sailors, or provide war relief to French families. Broadsides and event programs document her attendance at benefits and rallies, while songs and poems clipped from newspapers illustrate her patriotic interest.

Red Cross working party in University Hall, undated

On the outbreak of war, local Red Cross working parties formed across the country to organize the supply of hospital clothing including socks, shirts, blankets, and belts for soldiers. From November 1917 through February 1919 female students, faculty wives and members of the University Circle met every Thursday between 10 a.m. and 5 p.m. in the Red Cross Room in University Hall to assemble essential hospital supplies. The results were 1,332 knitted articles, 726 hospital and refugee garments, and 22,600 surgical dressings.

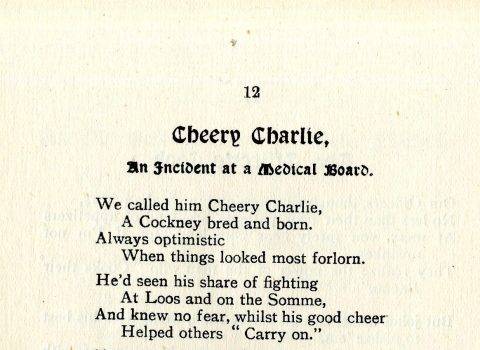

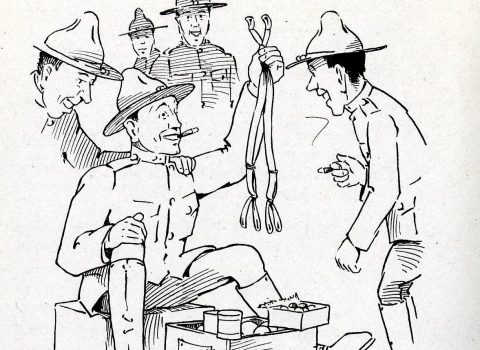

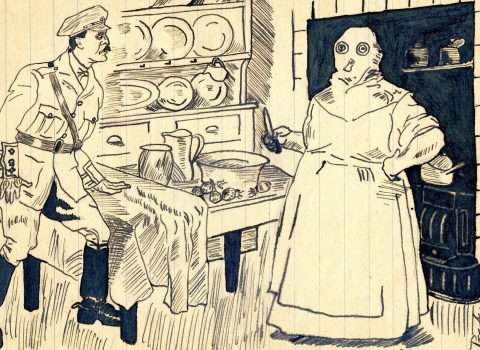

Passing Time

Even in war, periods of inactivity punctuated intense bursts of action. These artifacts held in University Archives reveal that, when faced with boredom or sorrows, service men and women could find a measure of solace in creative ways.

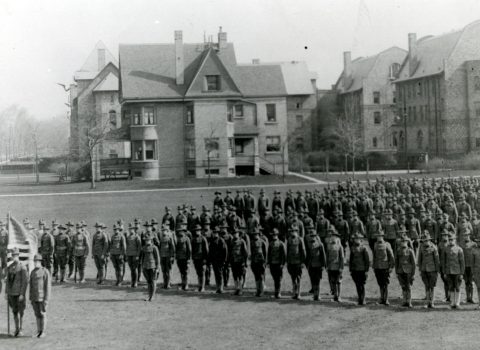

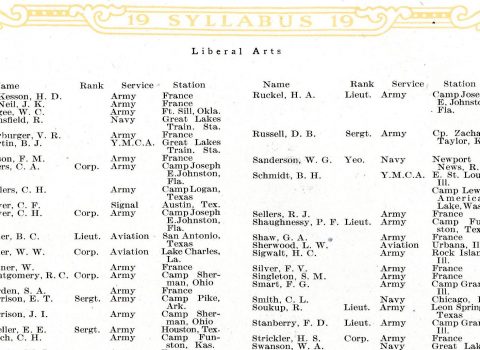

Alumni & Faculty at War

The administrative offices of the schools tried to keep records of students and faculty who left for a variety of war duties. According to the President’s reports from 1916-1919, 121 faculty members were absent on leave, 1071 students withdrew for National Service, and 1892 alumni. Specifically trained at Northwestern for Army or Navy service were a total of 3606 commissioned officers and enlisted men.

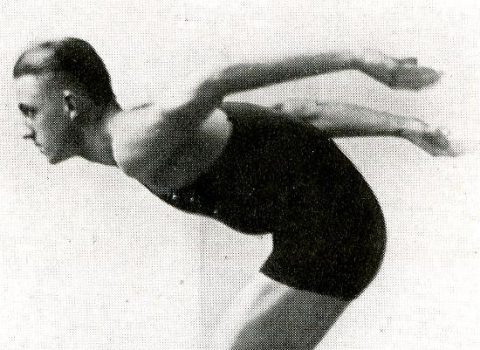

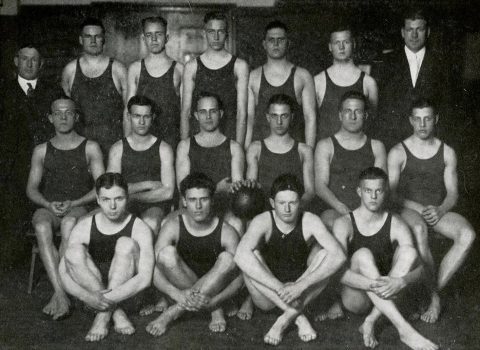

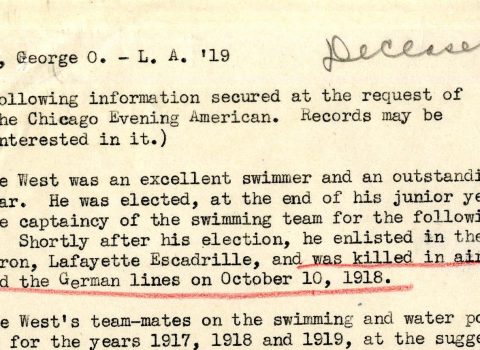

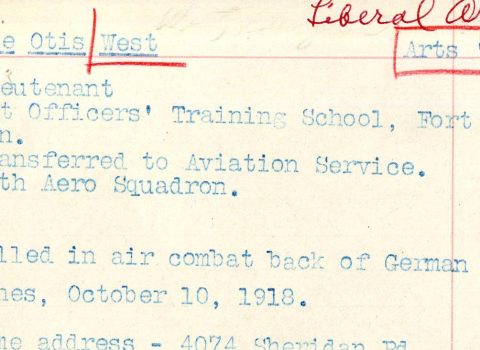

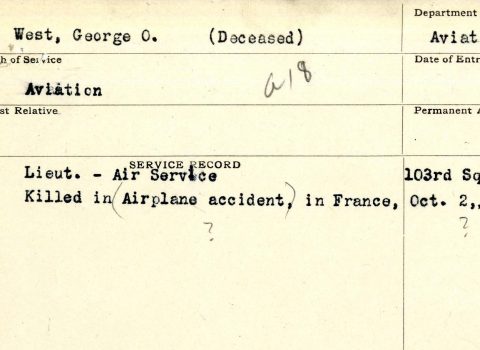

George Otis West, alumnus

West was a student in Northwestern’s Liberal Arts College and captain of the water basketball team until he withdrew from college for military service in 1917 to join the 49th Aero Squadron. On October 10, 1918, Lt. West was killed on the Flanders front in aerial combat. This active Northwestern alumnus was a decorated athlete, and University Archives is lucky to have so many artifacts that commemorate his time on campus.

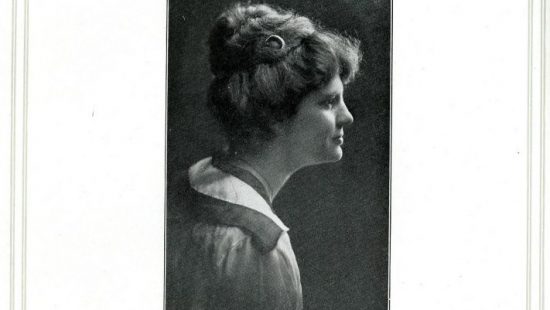

Frances Poole, alumnus

The Syllabus, 1920

Frances Poole was an Evanston resident who attended Northwestern’s College of Liberal Arts from 1907/08 through 1911/12. She left the University in her junior year to enter a nurses training course. Poole enlisted as a Red Cross nurse and was assigned to the General Hospital at Fort Ontario, Oswego, New York, where she cared for wounded soldiers. The Northwestern University yearbook from 1919 wrote about her daily life as an army nurse: “Except for two hours rest, she worked from four in the morning to seven at night, and often gave assistance to the night nurses after that. Because of weariness and exposure she contracted the influenza but refused to go off duty.” Five days later, on October 8, 1918, Poole passed away.

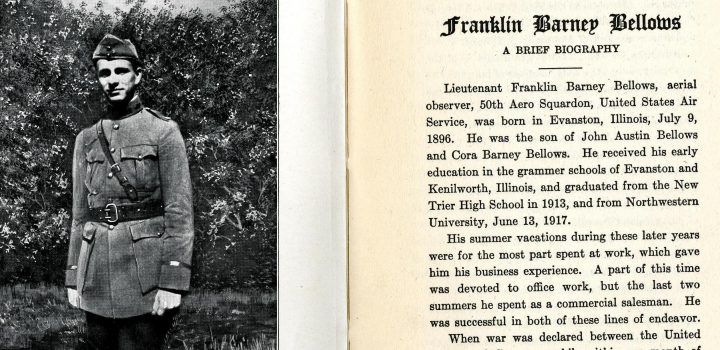

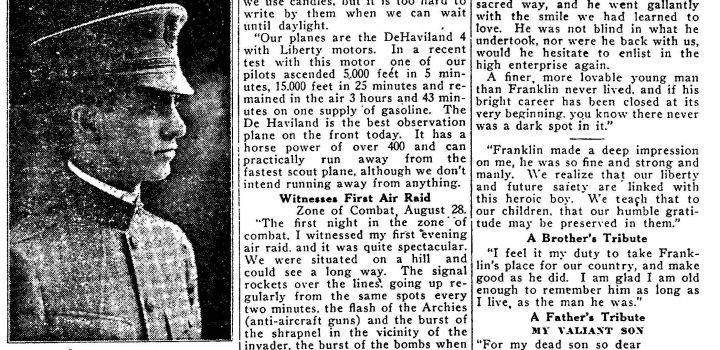

Franklin Barney Bellows, alumnus

After Bellows graduated from Northwestern in 1917, he enlisted in the first officer’s training camp at Fort Sheridan. In November 1917, he was assigned to the 50th Aero Squadron. On Sept. 13, 1918, while performing a reconnaissance mission, Bellows’ plane was shot down and he was killed near Saint Mihiel, France. In 1933 the auxiliary flying field at Waimanalo Military Reservation, Territory of Hawaii, was designated as Bellows Field in his honor.

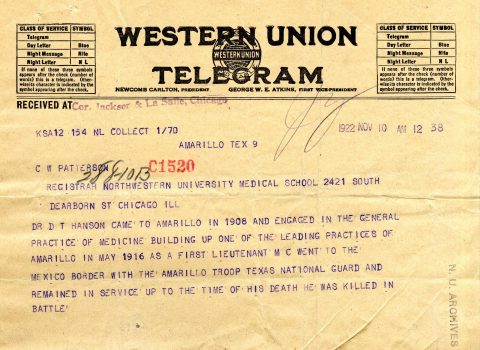

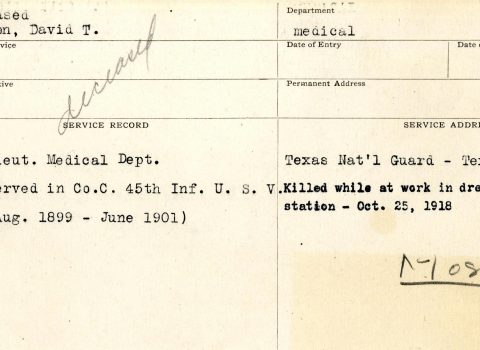

David Thomas Hanson, alumnus

After entering Northwestern’s College of Liberal Arts in 1897, David Thomas Hanson left for two years to volunteer in the Spanish-American war. He returned to the University in 1901 and graduated in 1905. After finishing Northwestern’s Medical School in 1909, he left Illinois to become a practicing physician in Amarillo, Texas. When the United States entered World War I, Hanson enlisted. He was promoted to Captain of the Medical Corps in April 1918 and was assigned to 36th Division, 142nd Infantry. In July 1918 Hanson arrived in St. Étienne-à-Arnes, France. Only a few months later, on October 8, 1918 he was killed in action while helping a wounded soldier. The Alumni of all Northwestern’s schools dedicated a bronze plaque placed on a granite boulder on the South Evanston campus in Nov. 22, 1922.

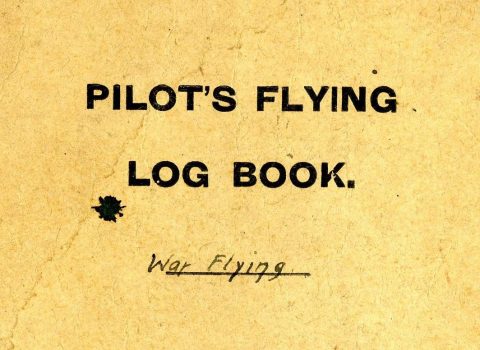

Lawrence Theodore Wyly, faculty

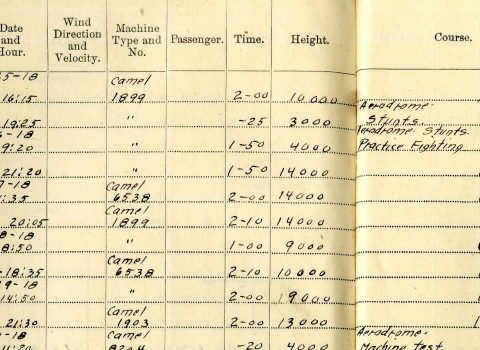

Like all pilots during World War I, Lt. Lawrence Theodore Wyly adhered to strict record keeping of every flight he made in his Camel biplane. The remarks column describes the tasks of the pilots, who were flying almost daily, if not several times a day. Wyly was a member of ‘A’ Flight of the 148th American Aero Squadron in France from July through November 1918, when his commander wrote about him: “I cannot recommend Lt. Wyly too highly and will say that he is a man that a flight commander is proud to have in his flight. If he has few Huns crushed, he has also been the means avoiding possible casualties.” In 1938, Wyly came to Northwestern as an assistant professor of civil engineering.

Walter Dill Scott, faculty

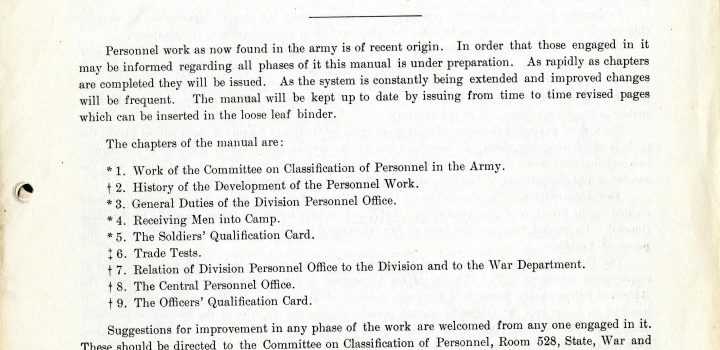

Walter Dill Scott joined the University in 1900 as instructor in psychology and pedagogy; by 1909 he was appointed head of the new Department of Psychology. Northwestern granted Scott a leave of absence from 1916-18 to serve as director of the new Bureau of Salesmanship at the Carnegie Institution of Technology. There, Scott studied the application of scientific knowledge to business problems. By the time of the First World War, he was well-equipped to test, evaluate, and utilize the talents and skills of large numbers of people. In June 1917, the staff of the Bureau voted unanimously to donate their services to the war effort. Scott devised and offered to the Army a proposal for selecting officers by scientific methods, which received a trial run at Fort Myer, New Jersey. The Fort Myer experience produced such favorable results that Scott was given another chance at Plattsburg Barracks in upstate New York, an officer training camp. After a vigorous effort, Scott was finally able to win approval at Plattsburg for his method. It was so successful in selecting good officers that it was later used to determine promotion and, most importantly of all, to determine effective use of the vast pool of talents and skills among enlisted men. For this work, Scott, who was discharged as a colonel, was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal in 1919.

In the Aftermath

After Germany signed an armistice agreement on Nov. 11, 1918, postwar America tried to put the horrors of war behind it. After honoring and remembering its dead, it began to embrace the diversions of the Jazz Age. Amid the jubilation, the country debated its need to isolate itself from future turmoil abroad.

Honorary Degree Ceremony, 1922

On April 17, 1922, Marshal Joseph Joffre, the “hero of the Marne and idol of America in those days just after the United States entered the World War I,” received an honorary law degree, presented by Northwestern president Walter Dill Scott (standing, right). Also present at the ceremony were professor of Latin and former chairman of the faculty athletic committee Omera F. Long (second from left), professor of history and dean of The Graduate School James A. James (third from left), and Professor of Romance Languages Edouard Baillot.

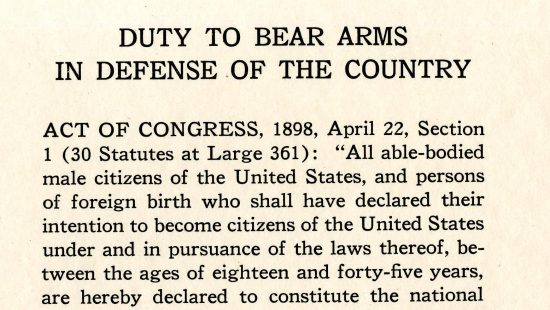

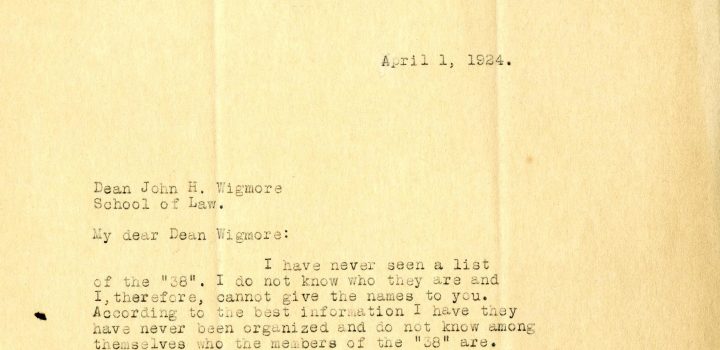

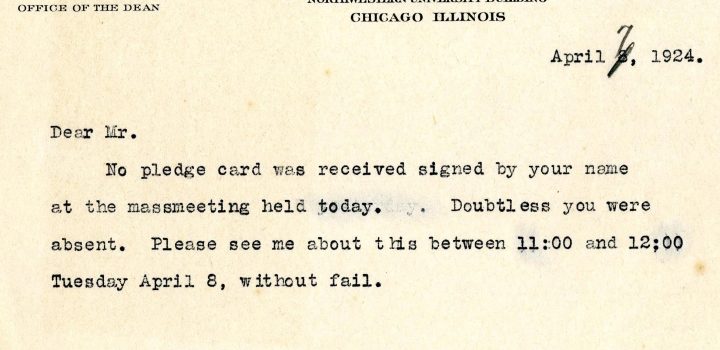

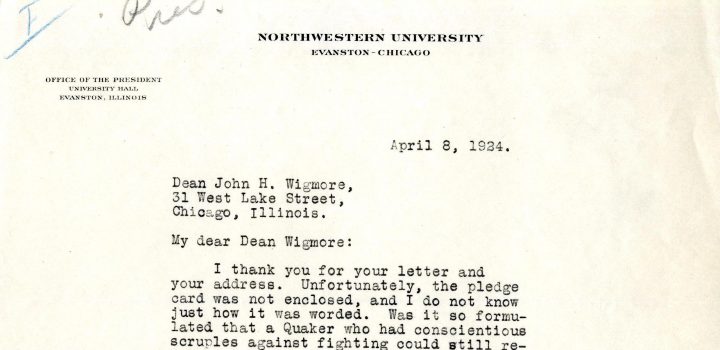

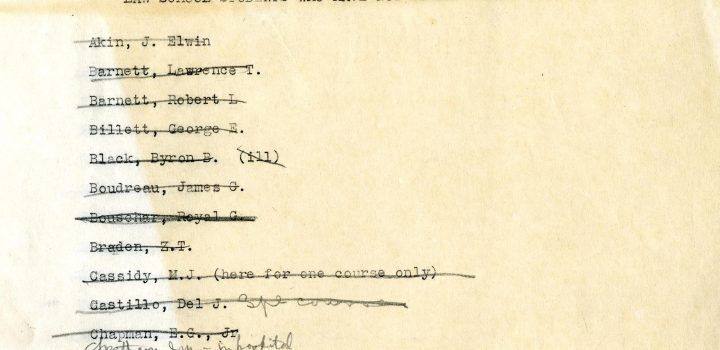

Duty to Bear Arms in Defense of the Country, pledge pamphlet, 1924

In 1924 an incident divided the Evanston community and Northwestern University. On March 23, Brent Dow Allinson, a University of Chicago and Harvard graduate, held a speech in the First Methodist Church in Evanston on the subject “the Youth Movement in Germany.” Allinson was a member of a group pledging themselves to refuse military service in wartime on the grounds that war is a denial of Christian principles. He himself was a deserter and had spent some years in prison. Several Northwestern students, supported by students of the affiliated Garrett Biblical Institute, were part of this group. Angry letters from faculty, businessmen and residents reached the Northwestern president Walter Dill Scott, calling Northwestern a “pacifistic” school. Allinson became the target of many members of the community Henry Wigmore, dean of the Law School, even created this pledge of military service and coerced law students to sign. When some refused, Wigmore demanded lists of those who disobeyed. Included in this case is some of the correspondence between Wigmore, Scott and other officials debating the matter.

More Information

These items are housed in the University Archives of Northwestern University Libraries.