This Sunday marked the 25th anniversary since the passing of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), a federal civil rights law that protects against employment discrimination and mandates accessible public spaces, transportation, government facilities, and telecommunication systems.

One-fifth of the U.S. population, or 56.7 million Americans, have physical or mental disabilities, and have historically fought a number of civil rights battles – from recognition as a very present and important population to challenging negative medical labels and ideas of “disability.”

While ADA changed many Americans’ lives for the better, and though the law didn’t specifically address public and higher education beyond physical accessibility, the generation of individuals who will truly see its justice are those you may share a class with this fall.

“When a law is passed, we know it takes a few years for states to implement it, so who’s the first to benefit from [ADA]?” AccessibleNU Director Dr. Alison May said. “The ones born in the mid-90s, the college-aged ones today.”

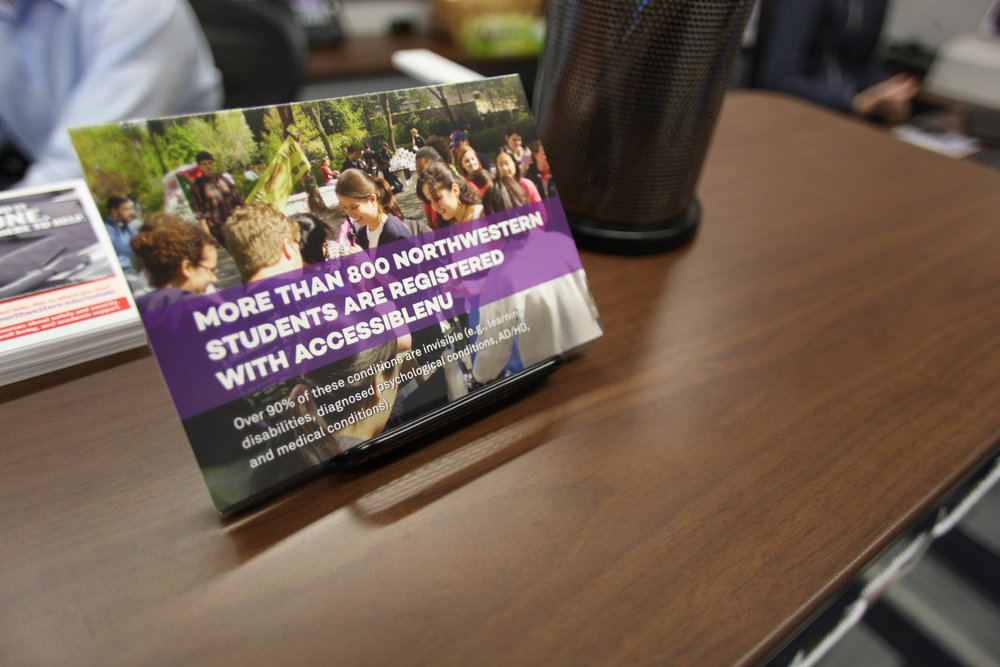

AccessibleNU was founded in 1997 as Disability Services, “pretty late to the game” compared to other universities, according to May. The office now serves 827 students between the Evanston and Chicago campuses, with 600 on the Evanston campus alone. The total number of students has increased around 17 percent every year – a long shot from its 20 registered students in 1997 – and May said it’s “not because we changed our documentation guidelines.”

“I think it’s several things – decreased stigma about registering, increased awareness,” May said. “Six to seven years ago, counseling services didn’t realize prolonged anxiety might need redirection to AccessibleNU.”

The office advocates for students on many fronts, including the fight to ensure physical accommodations – like ramps, elevators, and push-to-open buttons for doors – across campus.

Northwestern’s beautiful, but sometimes roughly 150-year-old buildings weren’t built with disabled community members in mind, and even in 1990 students in wheelchairs couldn’t take classes in Annie May Swift, Locy, Harris, or University halls.

The office itself was only relocated from the basement of Scott Hall – where May said students oftentimes didn’t have a seat or couldn’t access it – to a fully-customized space “that is probably the most accessible first floor on campus” at 2122 Sheridan in 2014.

Despite ADA and early 90s Northwestern student handbooks mainly addressing physical disabilities, May said 90 percent of the students AccessibleNU serves have “invisible disabilities” such as learning and sensory disabilities, psychological conditions, and autism spectrum disorders.

May said she feels as though the general campus climate is “accepting…the issue most of campus faces is not knowing,” referring to students with invisible disabilities, and a highly academic culture on campus where students “don’t want to be perceived as weak or struggling.”

AccessibleNU also offers test proctoring – utilizing its new one-way mirrors and cameras to monitor students if they have questions – and a number of guidelines for faculty and staff on how to students feel comfortable asking for accommodations or alternative assignments. The office also works heavily with Student Affairs Information Technology (SAIT) to ensure University websites are accessible to students as well.

May said that though the office sometimes receives “pushback and ableist comments,” if anything faculty tend to “over-accommodate” even as the number of students registered with the office has increased.

Even though there are still improvements to be made across campus – and the office’s 2014 name change to AccessibleNU emphasizes it is a campus wide responsibility – May said it’s clear Northwestern is listening.

“The office renovation, hiring more full-time staff, especially in this economy…the shift in this last year makes us feel like we’re a priority to this university, and that the university is going in the right direction,” May said.

As for ADA’s impact on the country 25 years later, May pointed out that unemployment for Americans with disabilities has not improved, and that the society stills lacks the mindset that disability is a domain of diversity, rather than a detriment.

“It’s about re-envisioning disability,” May said. “That these accommodations are essential, a civil right, and disability is something we may all have experience with one day.”