Learning: 1864-1874

After graduation, Willard took teaching jobs in small schools in Evanston and Chicago, the North Western Female College, the Pittsburgh Female College, and, as preceptress, at the Genesee Wesleyan Seminary in New York (later Syracuse University). By 1864 Willard was well enough known in Evanston to be named the Corresponding Secretary of the American Methodist Ladies Centenary Association, which was working to raise money for a new dormitory for Garrett Biblical Institute. Although the Association, like other such organizations, was run by men, women gained significant leadership experience from their participation. The campaign was a success; Heck Hall (named for Methodist Barbara Heck) opened in 1866 on the site now occupied by Deering Library.

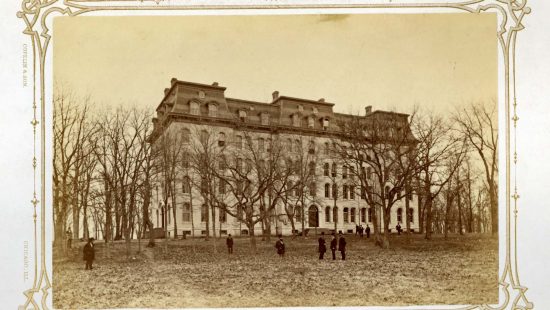

Heck Hall, circa 1874. FWHA

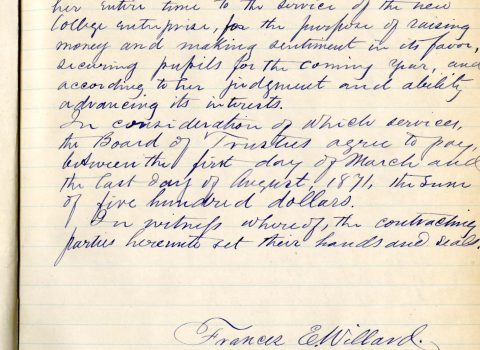

The new dormitory for the Garrett Biblical Institute, built in 1866, was funded by subscriptions raised by the American Methodist Ladies Centenary Association, with Willard as corresponding secretary. Her letter-writing campaign expanded her circle of acquaintances and resulted in $30,000 in subscriptions. Heck Hall housed Garrett’s students—known as the Bibs—until it burned down in 1914.

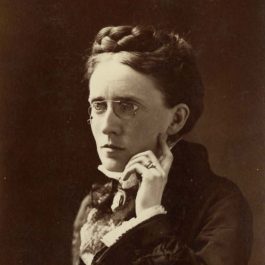

Women of Methodism, 1867. United Library/Garrett

This book was commissioned by the American Methodist Ladies Centenary Association as a gift in return for pledges. Willard’s successful fund-raising (despite her avowed lack of accounting skills) brought recognition from outside her local area when she was one of two dedicatees (the other was the Bishop’s wife) acknowledged in the preface of the history.

The beginning of Willard’s public work

From 1869-71, Willard accompanied a friend traveling through Europe and the Middle East. On her return, the women of the First Methodist Church asked her to speak about her experiences in missionary countries. Despite her fears of speaking before a group, the talk went so well that she gave it again before other groups of churchwomen. Then the bishop asked her to speak before an audience of women and men. She later wrote that “from that time dates my public work.”

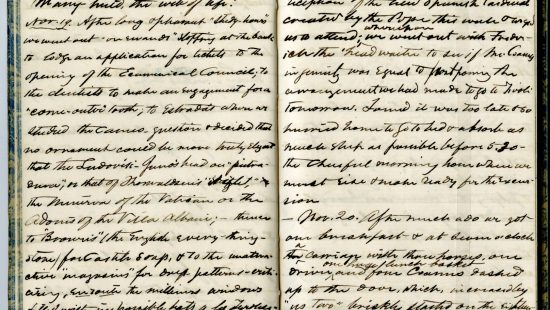

Willard’s Diary, Vol. 33 (November 9-December 25, 1869).

Willard, a diarist by nature, kept exhaustive journals (about 20 small volumes) of her travels, documenting events and conversations, and recording detailed impressions of what she saw. She was able to draw upon these experiences for her first public speaking efforts—and they remained vivid for her during the rest of her life.Transcriptions of Willard’s journals are held in the NU Archives, and are excerpted in Writing Out My Heart, by Carolyn DeSwarte Gifford. The original volumes are held in the Frances Willard Memorial Library and Archives.

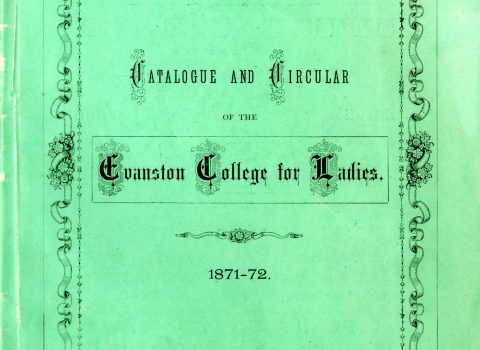

Willard and Northwestern: The Evanston College for Ladies

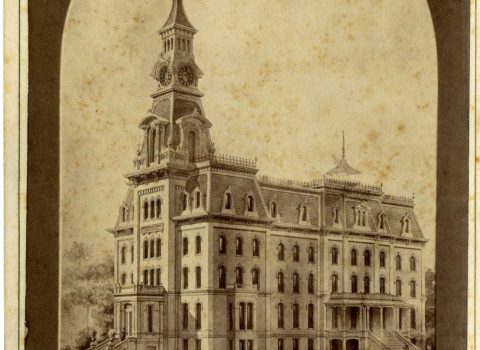

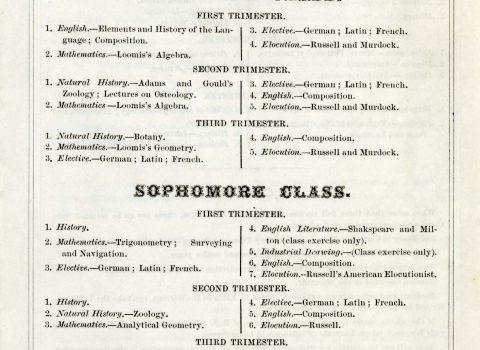

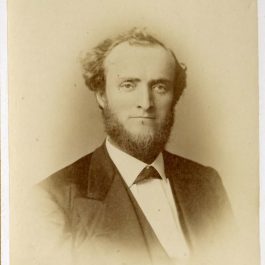

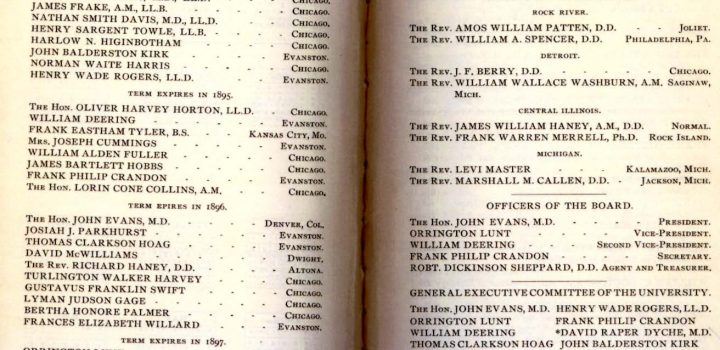

By 1871, Willard’s alma mater, the North-Western Female College, was in decline. In addition, Northwestern University had just opened its doors to women, at the prompting of its president, Erastus Haven. A group of Evanston women formed the Woman’s Educational Aid Association to absorb the old Female College and to assist NU’s women students with housing and academic services. Willard was asked to serve as President of the new Evanston College for Ladies.

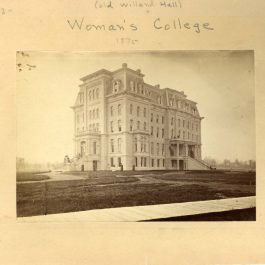

Willard plunged energetically into her new duties, which included fund-raising for a college building. Drawing on her experience with Heck Hall, she planned an ambitious event, a “Woman’s Fourth of July” with parades, speeches, and a baseball game. The campaign was a success, the first students arrived, and construction of a new building for the Evanston College for Ladies got underway on land donated by NU.

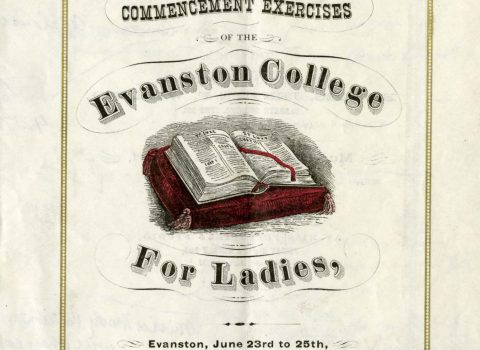

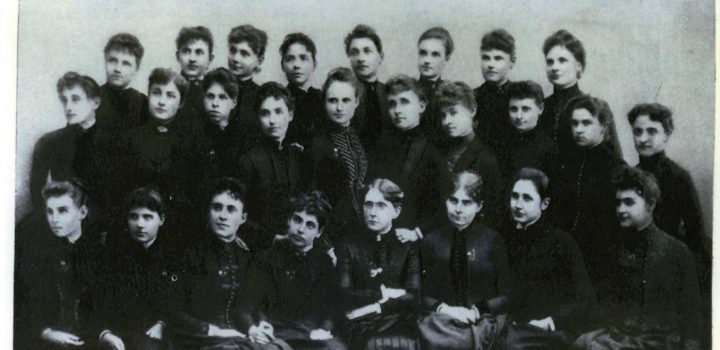

However, the great fire in Chicago that October prevented donors from meeting their promised pledges. The Evanston College for Ladies agreed to merge formally with Northwestern to become the Woman’s College of Northwestern University, with Willard as the first Dean of Women. The first and only commencement of the Evanston College for Ladies was held in June, 1872, with five graduates–reportedly “the first which ever received diplomas from the hands of women,” as well as the first to hear a woman deliver the baccalaureate sermon.

The Woman’s College of Northwestern

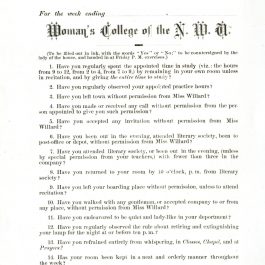

As Northwestern’s Dean of Women (she also taught aesthetics and rhetoric), Willard continued the policies she had put in place at the Evanston College for Ladies. One important feature was the self-report that each student was required to complete each week to monitor her own conduct and compliance with the College’s rules.

But Willard did not have the same authority as Dean as she had held as President. Although she and NU’s new president, Charles Fowler, both endorsed equal higher education for women and men, Willard believed that a different set of rules should govern women students’ behavior (in large part so that parents would feel safe sending their daughters to a coed college). Unable to resolve the differences with Fowler, Willard resigned from the deanship of the Woman’s College In 1874.

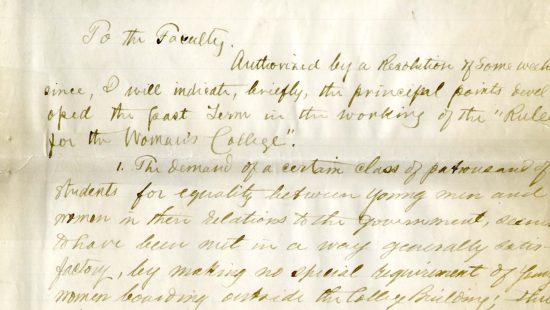

Frances Willard’s Resignation from Northwestern, Page 1. NUA

In a 15-page letter to the Trustees, Willard explained her differences with Fowler. It was clear that while Fowler was aiming for a co-educational college, Willard preferred the model of an institution with a men’s college and a woman’s college that operated separately.

After the Woman’s College

Despite her disagreement with Northwestern’s policies, Willard spoke warmly of the University, and of the professors and administrators who were her friends and neighbors in Evanston. She continued to be involved in the life of the University, especially in regard to the women students.

In 1882, when the sorority Alpha Phi came to NU, Willard became a member of the NU chapter (she had been inducted into the first chapter, in Syracuse, in 1875), and invited her young sorority sisters to visit her at Rest Cottage. In 1887, she served as national president of the sorority.

More Information

This exhibit features items from Northwestern University Archives (NUA)

and the Frances Willard House Museum & Archives (FWHA).