Radical Woman

The exhibit “Radical Woman in a Classic Town” provides a chronological overview of Willard’s life, from her student days at the North Western Female College to her leadership role in the WCTU, and focuses on the complex ties between Willard and the “Classic Town” — Evanston— that helped shape her vision of the world and her role in it.

Who was Frances Willard?

Frances Willard (1839-1898) is perhaps best known as the president of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, once the largest women’s organization in the country. Less well known is that behind her mild-mannered exterior were ideas and methods that were distinctly radical for her day, and that got their start right here in Evanston.

This page features a different Frances Willard, showing who she was in addition to her temperance work.

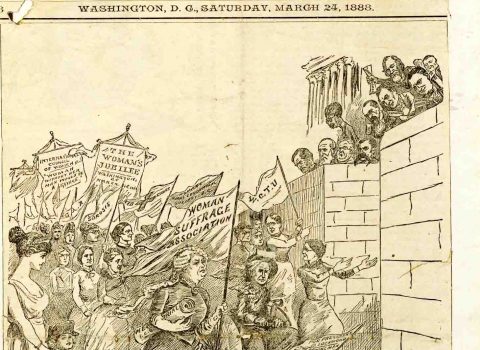

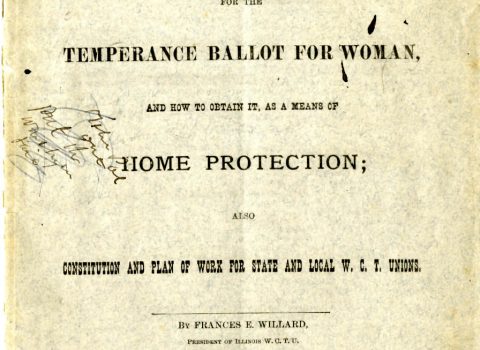

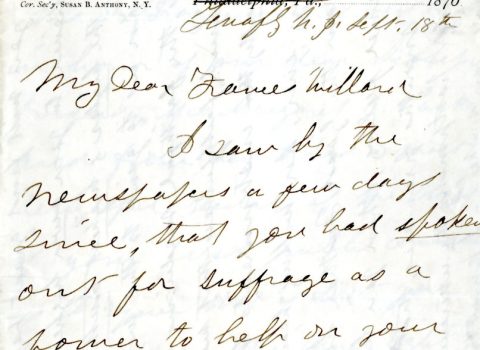

Suffragist

From a young age, Willard had believed that women should be able to vote. She brought the suffrage campaign with her when she became involved in the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, arguing that women could vote prohibition into law. Although many of the WCTU women across the country were not fully in favor of women’s rights, Willard herself was both vocal and active in her involvement in suffrage organizations.

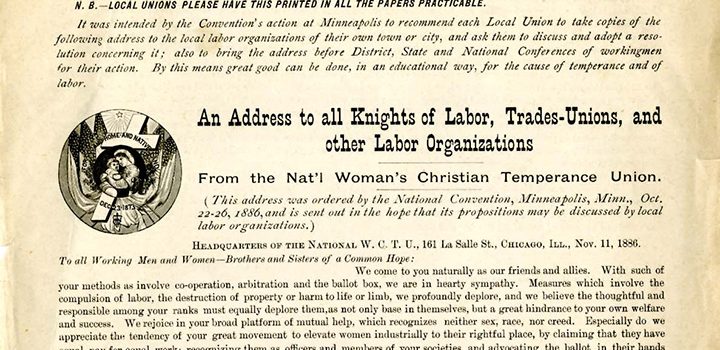

Christian Socialist

In addition to temperance and woman suffrage, Willard spoke, wrote, and took action in favor of the labor movement, prison reform, social purity, raising the age of consent, economic equity, and world peace. She joined the Knights of Labor and the Fabian Society, wrote for such reform papers as Our Day and WDP Bliss’s Dawn, and corresponded with many of the reformers of that busy era. She read the latest books on economics and social questions, and highly recommended Edward Bellamy’s bestselling Utopian socialist novel Looking Backward (1888). In 1893 she proclaimed herself a Christian Socialist. Late in her life, despite her failing health, she worked for the relief of Armenian refugees from Constantinople.

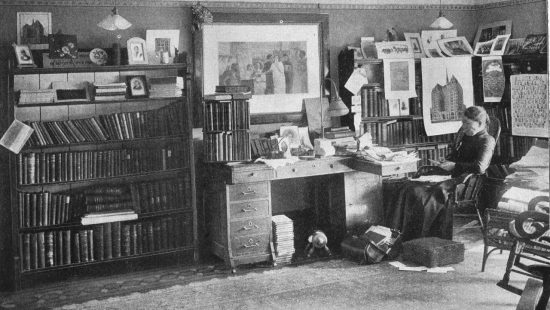

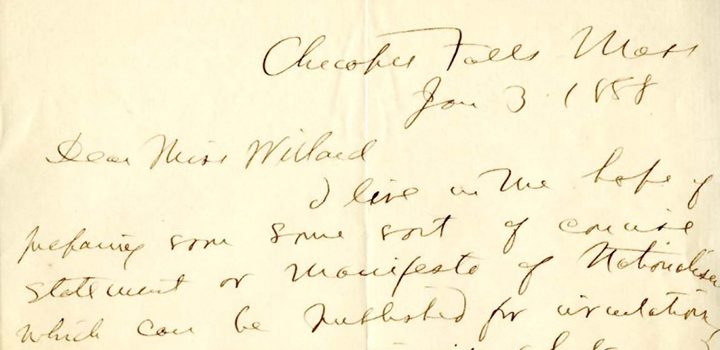

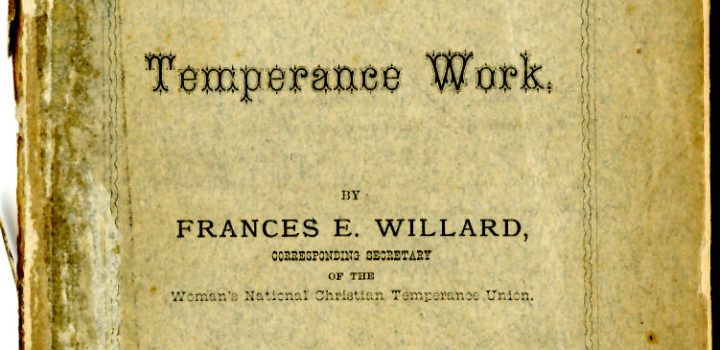

Orator and Writer

After her first efforts in front of the women of the Methodist Church in Evanston, Willard went on to a career of public speaking, in front of groups large and small, including men and women. Her speaking style was powerful, yet always described as “womanly” (never “strong-minded” or “mannish”), relying on a conversational tone and a supply of personal stories and quotations from poetry, the Bible, American heroes, and other reformers. The same accessible style infused her written work—voluminous correspondence, article after article for the WCTU’s Union Signal and other reform newspapers, and a dozen books encouraging women to transcend their traditional roles. Willard’s charismatic personality and understated approach, which came through in person and in print, made the broad platform of reform that she endorsed seem less radical than it was.

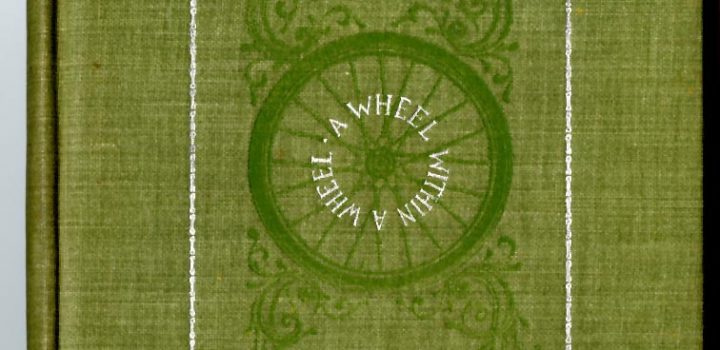

Bicyclist

Willard’s interest in reforms—especially those that would benefit women—extended to health and well being. She supported dress reform, became a vegetarian, and, in 1893, learned (with difficulty) to ride a two-wheeled bicycle—still a novelty for a woman–which she felt was a healthful and freeing mode of transportation which could be undertaken in a ladylike fashion. Her book describing her success in learning to cycle also served as a lesson in continuing to try new things.

More Information

This exhibit features items from Northwestern University Archives (NUA)

and the Frances Willard House Museum & Archives (FWHA).