Author: Ben Caterine, bencaterine2023@u.northwestern.edu, McCormick ‘23

If you watched ESPN or went on social media after the opening weekend of the NCAA Tournament, you were likely met with one overwhelming storyline: The Pac-12 exceeded all expectations, going 9-1 in the opening weekend and putting 4 teams in the Sweet 16, while the Big Ten went 7-8, with multiple highly-touted teams suffering upset losses in the first two rounds. Coming off a season in which the Big Ten was regarded as the preeminent conference in college basketball and the Pac-12 was largely forgotten amidst perceived mediocrity, these tournament results were shocking; they were exactly the kind of “madness” we’d missed last year. But to many fans, the results were a sign that the experts might’ve been wrong about these conferences all season long.

It is perhaps inadvisable to make too much out of the results of a single-elimination tournament, where any player or team is capable of having a bad game. However, in this case, the conferences performed so differently than expected that it’s worth considering what factors could have led to a possible misevaluation of the Big Ten and Pac-12. In this article, I’ll examine one theory and attempt to discern whether this year’s events were even that unique for the famously unpredictable NCAA Tournament.

A popular theory on social media for the Big Ten’s failures in the tournament has revolved around the idea of a “feedback loop”. The thought is essentially that the perceived strength and strong ranking of Big Ten teams caused their opponents — other Big Ten teams — to be ranked higher because they played a seemingly harder schedule. Then, these teams’ opponents — more Big Ten teams — were ranked even higher for the same reason. Strength of schedule (or some adjusted form of it) weighs heavily into important metrics like the NET rankings (see below) and BPI, which factor into the Selection Committee’s decisions and the overall perception of teams in weekly polls. A similar negative feedback loop could of course cause the Pac-12 to be collectively demoted as punishment for allegedly weak schedules.

However, in order for these loops to occur, the Big Ten teams must have somehow been ranked highly in the first place to initiate the loop. This could be due in part to factors like coaching and player recruitment ratings (important parts of preseason BPI calculations), but they are likely more directly attributable to the teams’ non-conference performance, since these games directly precede the conference season. So, I wanted to compare the Pac-12 and Big Ten’s non-conference schedules to see if any variations in degree of difficulty emerged:

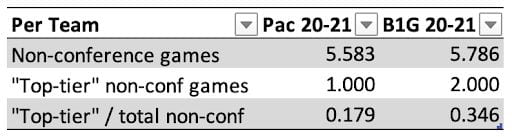

I compiled all of the Big Ten and Pac-12 teams’ non-conference schedules to produce the above table. As you can see, teams in each of the conferences played about the same number of non-conference games, but Big Ten teams averaged 2 games against “top-tier” conferences, while Pac-12 teams only averaged 1. I defined “top-tier” to include non-conference games against the Big Ten, Pac-12, Big 12, ACC, SEC, Big East, and American. The Big Ten’s more competitive non-conference opponents could help account for the disparate strength of schedule rankings heading into conference play. In fact, the Big Ten at one point held the top 14 spots in the national strength of schedule rankings, thanks in part to their difficult non-conference schedules and the aforementioned feedback loop phenomenon.

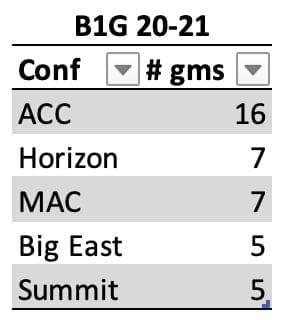

While looking at the data, however, I became more intrigued by just how geographically segregated the two conferences’ non-conference schedules were. Looking at the top 5 most common conferences faced, we see that the Pac-12 faced mostly western conferences, while the Big Ten faced eastern and central conferences:

This revealed another factor that could throw off strength of schedule ratings: Pools of isolated teams with very little intermixing can make it hard to standardize rankings across the pools. Essentially, the western group could be perceived as too strong or too weak compared to the east, since there is very little data directly comparing the two to each other. At first thought, this schedule segregation seems like a COVID issue; teams were forced to play largely local non-conference games to avoid excessive travel, creating these isolated geographical pools. However, I was curious about how the distribution would look in a regular year, so I took a look at the 2019-20 season:

Once again, the Big Ten averaged about 1 additional top-tier non-conference game, compared to the Pac-12. So, the hypothesis that a feedback loop was produced by unusual non-conference schedules in 20-21 doesn’t seem likely, since the schedules were similar the previous year. And, once again, the conferences’ non-conference opponents were geographically segregated, with the Pac-12 playing the most games against the West Coast and Mountain West Conferences, and the Big Ten most frequently playing the ACC, Big East, and all the other major conferences in the east. This means that the isolated pools don’t seem to be a unique product of COVID after all.

But if the Pac-12 is always on a schedule island, does this mean that the conference is often misjudged by rankings and the Committee? Well, yes. I took a look at the last 10 years of NCAA Tournament performance by the Pac-12, Big Ten, and Big 12:

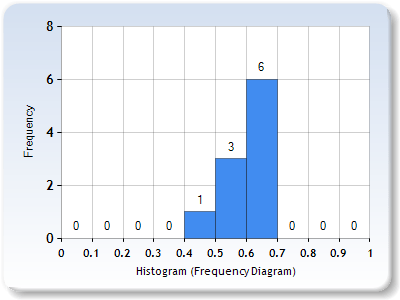

To better visualize the volatility of each conference’s performance, I constructed histograms, with winning percentage ranges on the x-axis and season counts on the y-axis:

The Pac-12 is by far the most inconsistent conference in the last 10 years of NCAA Tournaments. They have the three best performances on the chart, in 2021, 2017, and 2015, but they also have the three worst, in 2018, 2012, and 2016, and the standard deviation of their win percentage far exceeds those of the Big Ten and Big 12. Maybe the Pac-12’s unexpected success this year was not so surprising after all!

Or, maybe we’re making a mountain out of a molehill here. Again, March Madness is volatile by design; we’re not supposed to draw hard conclusions about the state of college basketball from an event that has never been perfectly predicted. Even this year, there’s reason to believe that some of the Big Ten/Pac-12 narrative is a bit flukey. Ohio State, Purdue, and Michigan State all lost in overtime in their first games, and Illinois lost to criminally underseeded Loyola. The Pac-12 lost its best-seeded member, Colorado, in the second round, and Oregon got a bye because of COVID.

Still, it’s hard to totally dismiss the narrative when three Pac-12 teams made the Elite Eight and the conference went 3-0 head-to-head against the Big Ten in the tournament, punctuated by UCLA’s victory over Michigan to go to the Final Four. This year’s tournament might finally bring attention to the Pac-12’s recent history of tournament volatility, and maybe it’ll even make the Selection Committee rethink how they rate the often-isolated Conference of Champions. Otherwise, don’t be surprised if the Pac-12 continues to defy March expectations in the future.

Sources

Team schedule information: https://www.sports-reference.com/cbb/schools/michigan/2021-schedule.html

NCAA Tournament records by conference: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2021_NCAA_Division_I_Men%27s_Basketball_Tournament

NET Rankings explained: https://www.ncaa.com/news/basketball-men/article/2020-05-12/net-explained-ncaa-adopts-new-college-basketball-ranking-replace-rpi

NCAA Selection Committee criteria: https://www.ncaa.org/about/resources/media-center/mens-basketball-selections-101-selections

End-of-season NET Rankings: https://www.ncaa.com/rankings/basketball-men/d1/ncaa-mens-basketball-net-rankings

Histogram tool: https://www.socscistatistics.com/descriptive/histograms/

Additional statistics and sources are referenced by links throughout the article.

Be the first to comment on "Conference of Confusion: The Pac-12’s March Madness Surprise"