Author: Mike Pastuovic (michaelpastuovic2023@u.northwestern.edu), Weinberg ’23

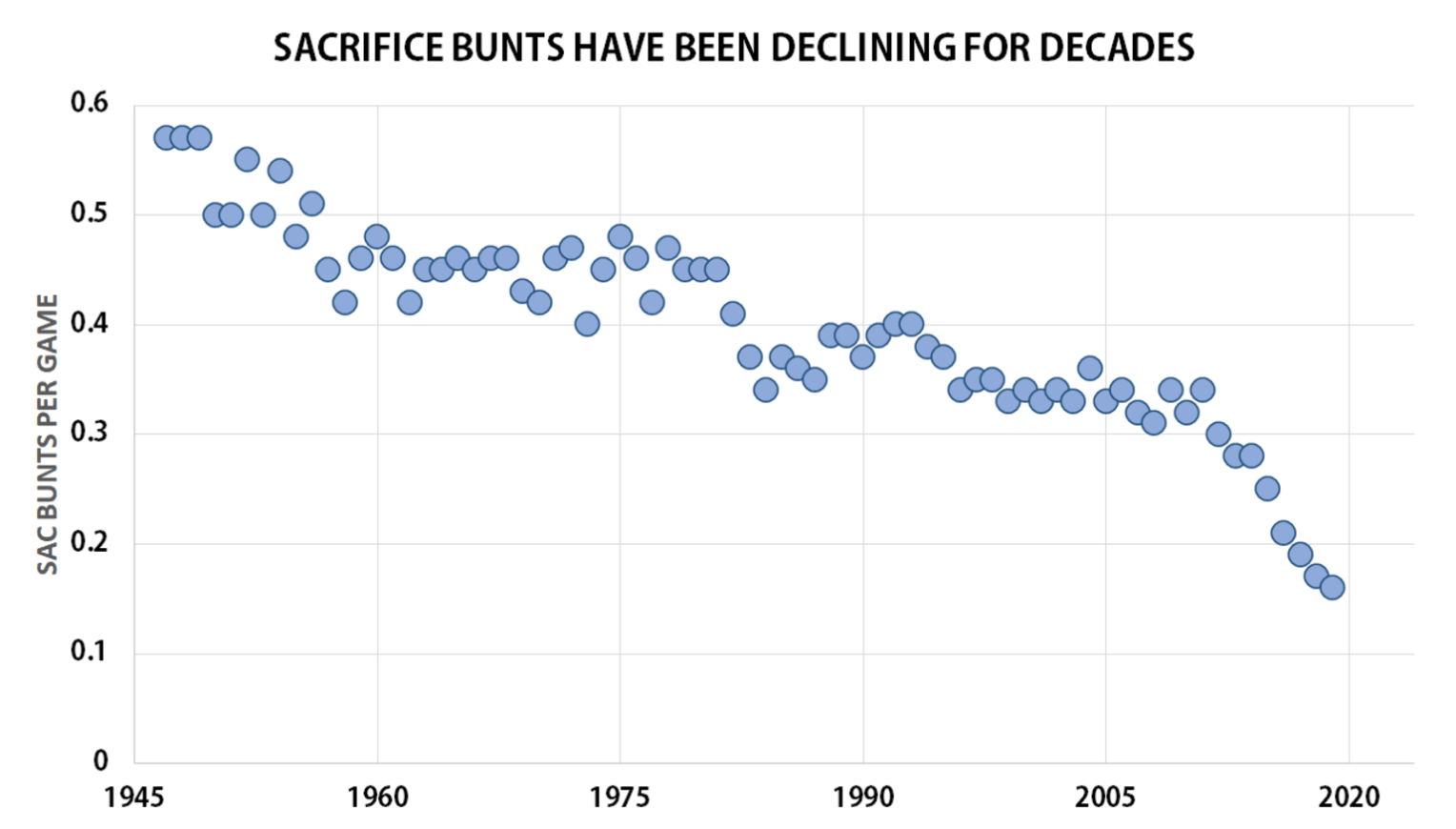

You do not have to watch 162 games a year to understand that baseball’s analytics revolution has changed the on-field product pretty dramatically over the 21st century. Baseball is becoming increasingly more about shifts, home runs, strikeouts, and walks, and less about putting the ball in play. The rapid decline of the bunt over the past 20 or so years has been one of the more notable changes.

MLBdotcom’s Mike Petriello mentions that bunting’s role in baseball will be further diminished by the eventual implementation of the DH in the National League. He includes the following chart, which illustrates just how rapidly the frequency of bunts in MLB has decreased recently.

Naturally comes the question, why are teams bunting less? Clearly, as MLB teams became more statistically adept, they came to the conclusion that bunting was less frequently optimal than in-game strategy decision-makers had thought previously. Surface-level explanations against bunting describe the silliness of giving a team a “free out” instead of trying to hit the ball over the fence.

While arguing that “bunting is bad” is not exactly an earth-shattering, original assertion, I think it is important to understand the mathematical underpinnings, beyond general semantic arguments, that led the baseball analytics community to this conclusion. I will next introduce a specific, common bunting situation and explain why bunting in this scenario, under most game and matchup conditions, is a severely suboptimal strategy. I will then argue that while this is true, there still remain conditions where bunting makes sense, suggesting that bunting is not on a path to extinction.

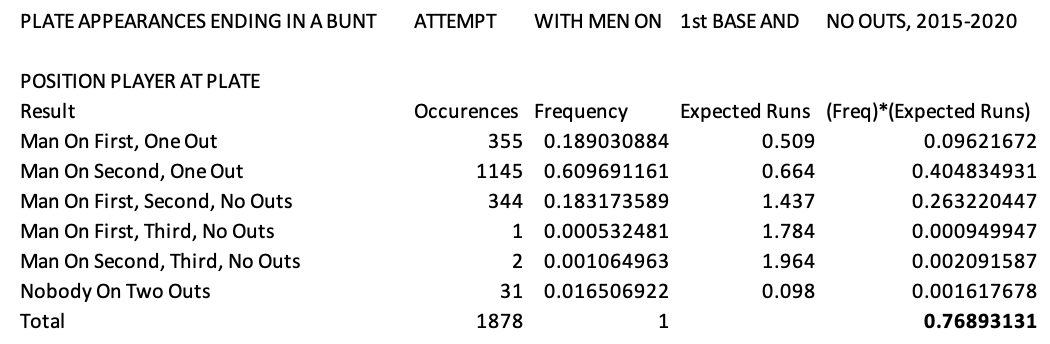

Using Baseball Savant’s “Search” tool, I was able to get data for every plate appearance with a man on first and nobody out that ended in a bunt or bunt attempt from 2015-2020. I grouped each datapoint based upon the number of outs and baserunner(s) and position(s) on the basepaths following the bunt or bunt attempt. Table 1 displays the outcomes of each bunt attempt by position players with a man on first and nobody out 2015-2020.

Table 1

I excluded the bunts of pitchers because it is invalid to assume that they would have anywhere near as much success at the plate compared to the league average position player. With this position player data, we can compare the expected runs for a given inning with a man on first with nobody out with the weighted expected runs associated with the outs/baserunner(s) after each of the bunt attempts.

Table 2

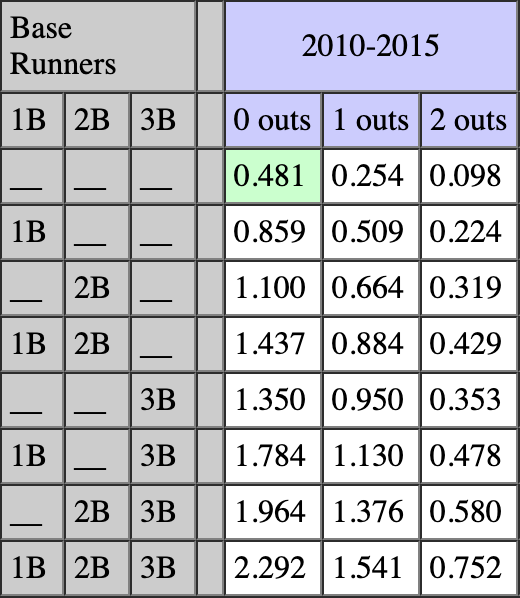

Table 2 displays Retrosheet’s 2010-2015 Run Expectancy Matrix, which shows the expected runs in a given inning associated with each possible out(s)/baserunner(s) situation. We can use this information to compare the expected runs associated with having a man on first with one out and the weighted average expected runs after teams bunt.

Table 3

As displayed in Table 3, our weighted average expected runs total following a bunt attempt by a position player from 2015-2020 is .7689. We can now compare this number to the expected runs associated with having a man on first and nobody out to make a conclusion about the effectiveness of bunting in this situation under average circumstances. Please note that some of these bunt attempts may include players attempting to bunt for a hit, which could lead to us overestimating the weighted expected runs associated with bunting with a man on first and nobody out.

We have now determined that when a position player bunts with a man on first with nobody out, that player’s team can anticipate an expected run decrease for that inning of 0.09. Over the 1878 data points, this would total a whopping 169.15 expected run decrease that teams realized over the 2015-2020 seasons by bunting with position players with a man on first and nobody out.

We have now determined that when a position player bunts with a man on first with nobody out, that player’s team can anticipate an expected run decrease for that inning of 0.09. Over the 1878 data points, this would total a whopping 169.15 expected run decrease that teams realized over the 2015-2020 seasons by bunting with position players with a man on first and nobody out.

Seeing that the average expected run decrease of a bunt is relatively significant can lead one to the conclusion that position players should never bunt with a man on first and one out. However, this would be an oversimplification and misinterpretation of the data. The expected runs totals used assume a league-average pitcher, batter, batter(s) to bat next, and baserunners. This 0.09 number lends intuition for why bunting is not the default with a man on first and nobody out and is not a mandate for the banishment of bunting with a man on first and nobody out.

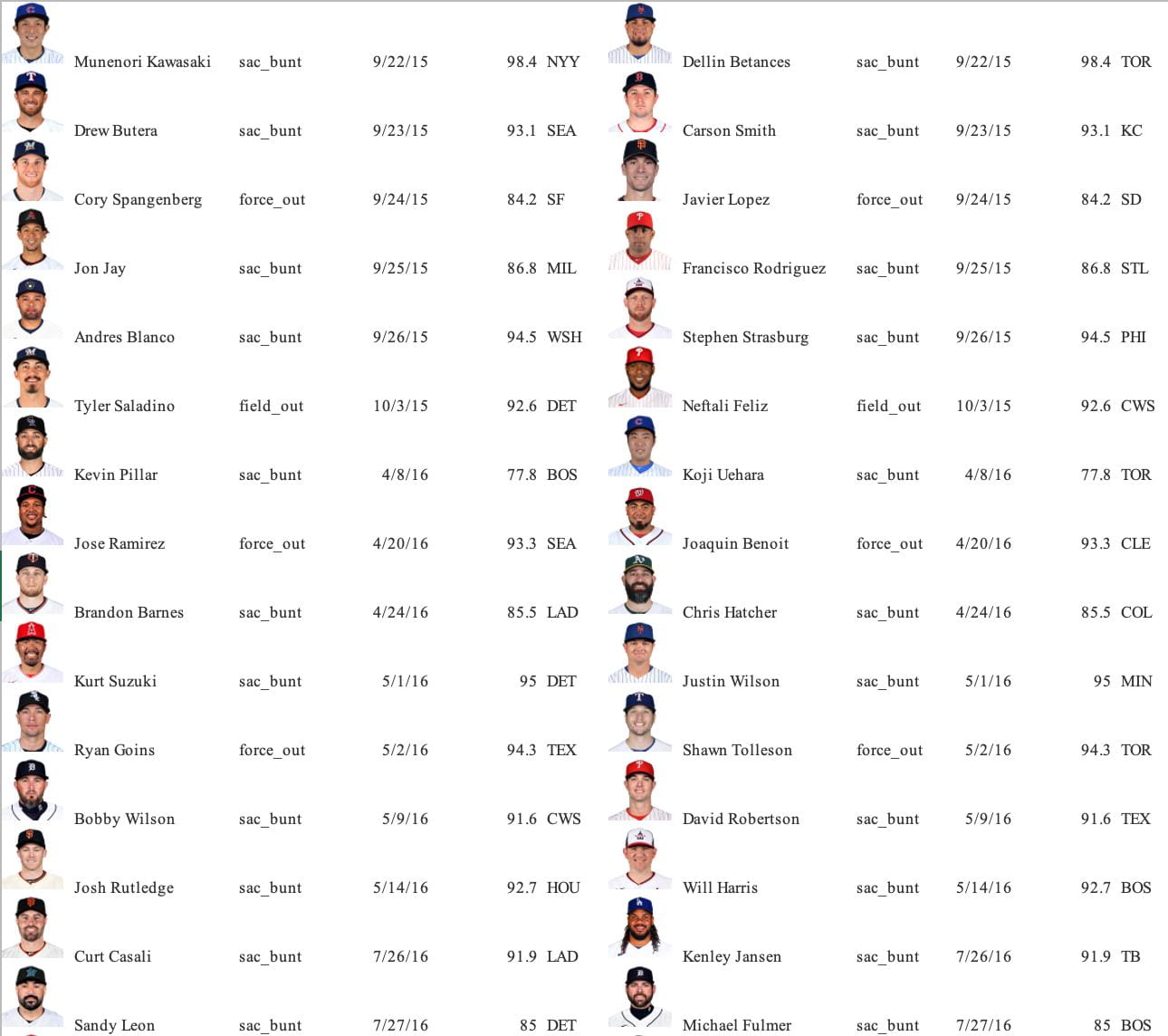

So in what game environments does it make sense for teams to bunt? Bunting is a more optimal strategy when there is a particularly poor matchup for the hitter, and teams are especially interested in scoring just one run (not adverse to lowering their variance of expected runs). Oftentimes, these situations arise in the late innings when relatively poorer hitters face high leverage, backend of the bullpen arms. To test this thought experiment, I again used Baseball Savant’s “Search” tool to see every time a position player bunted in a tie game in the seventh inning or later (excluding extras) with a man on first and no outs.

There was a surprisingly high number of data points (98) in this exact scenario over the six seasons, which leads me to believe that clubs understand that this is a particularly optimal situation to bunt in. Even more interesting is with which batters clubs decided to bunt with. Teams tended to bunt with relatively weaker hitters who are susceptible to hitting the ball on the ground, confirming our hypothesis that teams understand that special situations are required for bunting to be a legitimate choice.

Below I included some of these data points (man on first, nobody out, 7th/8th/9th inning, tie game, 2015-2020). In many cases, a particularly weak hitter is facing a particularly strong reliever.

There is solid, clear statistical evidence that the decline in bunting over recent decades is justified. In average, typical game situations, we see that bunting with a man on first and nobody out is suboptimal. This trend holds for other common bunting scenarios in average, typical situations. However, because lopsided, late-game matchups will always exist, bunting will remain a part of baseball. I predict that as analytics continue to play a large role in baseball, the frequency of bunts will converge to a lower, more stable level.

Sources:

http://www.tangotiger.net/re24.html

https://www.mlb.com/news/designated-hitter-national-league-sacrifice-bunts-decreasing

All Statistics used via Baseball Reference, Baseball Savant, ESPN, FanGraphs,

You assume the skills for fielding bunts remains constant.

Shift hitters sure need to learn