By Varshini Cherukupalli

Project Rural India Social and Health Improvement (RISHI) was founded in 2005 at the University of California, Los Angeles. Since then, chapters of Project RISHI have been established at eight other US universities, each partnering with a rural community in India. Chapters are involved in a series of initiatives ranging from water sanitation to maternal and child health education. In conjunction with local physicians and non-governmental organizations (NGOs), members plan projects throughout the academic year and implement them during summer or winter break trips to their respective partnered villages in India.

The Northwestern University (NU) chapter of Project RISHI was founded in May 2011. My close friend Manisha Bhatia and I were discussing a talk that we had just attended by Joia Mukherjee, the Chief Medical Officer of Partners in Health, which inspired us to—as clichéd as it sounds—do something “good.” I had heard of Project RISHI from peers at other universities and I proposed the idea of bringing Project RISHI to NU. Manisha and I, along with two other friends, Apas Aggarwal and Shreya Agarwal, joined together for this initiative. Since those initial conversations nearly three years ago, our chapter has grown to an organization with about 40 members, an executive board of nine undergraduates and two advisors at the Feinberg School of Medicine at NU, Dr. Mamta Swaroop and Dr. Anagha Loharikar.

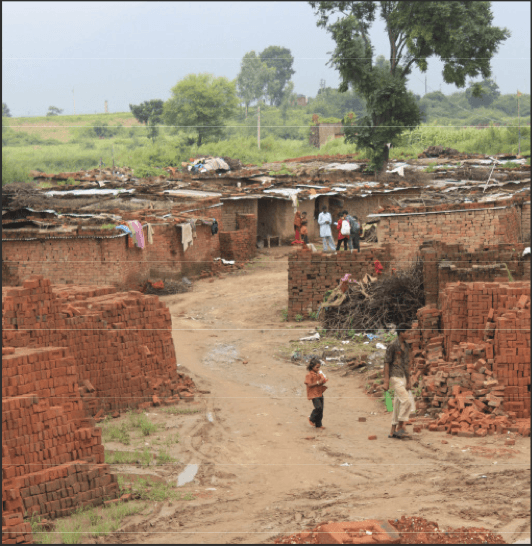

Our partner community, Charnia

Apas, Shreya, and I first visited Haryana, India during the summer of 2011. We had contacts at the Param Seva Trust, an NGO based in the capital city of Chandigarh, that is dedicated to improving access to education and healthcare. Members of the Trust accompanied us as we visited several rural communities and conversed with the Panchayat, or governing council, of each village. Towards the end of the trip, we traveled about an hour from Chandigarh to Charnia, a rural area located against the breathtaking backdrop of the Himalayas.

Charnia is a stratified community made up of several brick manufacturing zones and constructed villages. Each brick zone has a privately owned factory. In each zone, 100-200 migrant brick manufacturing laborers live in makeshift brick stacks supported by mud. The laborers have access to water from nearby government-owned pumps, and occasional access to electricity in the evenings. When the monsoon season occurs each year (July through September), some laborers temporarily move to other states in search of employment, while others continue to live in Charnia. Thus, the population of brick laborers changes constantly. In contrast to the brick zones, Charnia also has areas that resemble the typical Indian village: small houses made of concrete are situated on winding streets in the midst of green fields. Most of the farmers and individuals who are employed in local cities live in these non-brick areas of Charnia. The difference between the brick and non-brick communities struck us as we walked through the village. Based on our discussions with various residents, we decided to focus NU Project RISHI’s efforts in Charnia to improve access to high quality healthcare for the community members most in need.

Determining Charnia’s needs

The following summer (2012), we traveled to Charnia for the second time—this time, with eight new NU Project RISHI members. Our primary goal was to conduct in-depth needs assessments designed using World Health Organization (WHO) resources [1]. These household surveys covered a series of topics including demographics/education, sanitation, nutrition, general health, trauma/injury, and reproductive health. Every day, our team would divide up into pairs—one Hindi speaker and one recorder—and visit households to conduct the surveys. We were able to complete 190 surveys in two weeks.

The responses we received varied immensely by socioeconomic class and geographical area within Charnia. For instance, 75.8% of individuals in the brick communities reported that they had no formal education, as compared to 41.2% of the of the non-brick population (p<0.0001). Moreover, we found that women from the brick laborer population visited the doctor fewer times on average during pregnancy than the non-brick population. Of all the individuals surveyed, 24.1% reported at least one household member suffered from anemia, 32.1% from hypertension, 18.2% from hypotension, and 23.5% from typhoid fever. Although the brick laborers were geographically proximate to the non-brick laborer population, they were generally of a lower socioeconomic class, which resulted in health disparities.

Towards the end of the trip, we organized a health camp with the support of two medical institutions, the Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research (PGI) and Maharishi Markandeshwar University (MMU). Physicians provided free specialized care to the villagers, and we were thrilled that we could give them the medical attention they deserved.

Initial obstacles

During data collection, our team faced several challenges. Many of us did not speak Hindi, and it was frustrating when we were unable to understand the villagers’ responses. However, we quickly learned to communicate with basic words, as well as through non-verbal gestures and facial expressions. Each day of surveying was unpredictable, and every evening, we revised the survey and discussed important issues we had observed. We were simultaneously exhausted and enlightened—inspired to make a difference but unsure of where to start.

The personal connections we formed with families in Charnia were our greatest sources of motivation. Each of us has memories surveying villagers who were overwhelmingly friendly and welcoming—the amount of chai we were offered reflected this hospitality. Upon returning from our trip that summer, we knew that we had to plan sustainable health interventions to encourage positive behavioral change in Charnia.

Moving forward: targeting anemia

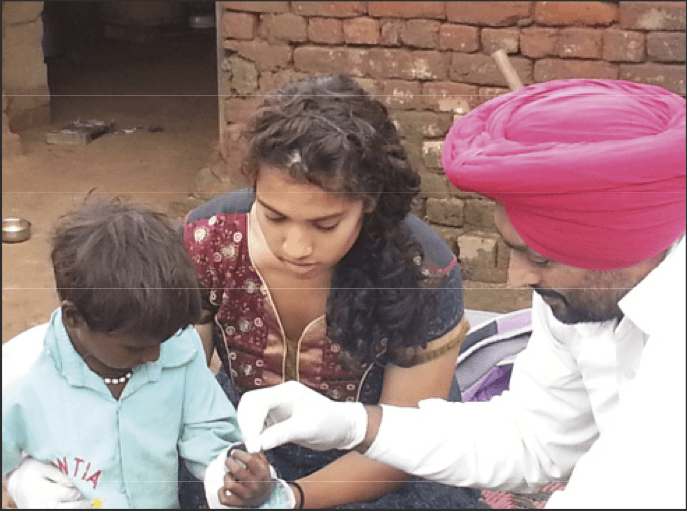

The author assists a technician from the Postgraduate Institute of Medicinal Education and Research (PGI) with conducting hemoglobin testing in one of Charnia’s brick manufacturing areas. Photo by Edwin Park.

The needs assessments indicated a potential need for a targeted anemia intervention and the small sample of hemoglobin measurements collected at our health camp supported this need. Anemia is currently recognized as one of the most widespread public health concerns globally, and is clinically characterized by decreased hemoglobin concentrations [2]. More than 30% of the world’s population is anemic, and it is particularly prevalent in developing countries [3]. In Southeast Asia alone, 65.5% of preschool age children, 48.2% of pregnant women, and 45.7% of non-pregnant women are affected by anemia [3]. Addressing childhood anemia is of particular importance because it impacts cognitive and psychomotor development [4]. Moreover, maternal anemia increases the risk of maternal mortality, low birth weight, and preterm delivery [5]. In India, 89 million children are anemic, with most residing in rural areas [6].

Anemia is attributed to nutritional deficiencies of iron, folate, and vitamin B12 with infection potentially exacerbating the condition [2]. Iron/Folic-acid (IFA) supplementation programs are commonly utilized to reduce Iron-Deficiency Anemia (IDA). However, compliance and delivery systems are major issues with these programs. Side effects of the medication such as epigastric discomfort, constipation, or diarrhea discourage individuals from adhering to the daily IFA regimen. Community participation is necessary for successful IFA program implementation, along with diet-based approaches [7].

To analyze the prevalence of anemia in Charnia, we needed more hemoglobin data—specifically from the women and children of the brick manufacturing zones. This was our first goal when we visited Charnia during the summer of 2013. The team performed 113 hemoglobin tests on the women and children in the brick zones in August 2013, and physicians provided clinical diagnoses of IDA according to symptoms of conjunctival pallor, soreness of tongue, brittle nails, and pale palm or soles; cardiovascular signs of anemia; and pregnancy status of the women. The hemoglobin threshold for anemia in children, pregnant women, and non-pregnant women of reproductive age is between 11.0-12.0 g/dL, yet the mean hemoglobin level of the individuals tested in Charnia was 10.08 g/dL [7]. The prevalence of anemia in the brick zones was 78.8%. Of all of the 113 individuals tested, 89 had hemoglobin levels lower than 11.0 g/dL.

The high rates of anemia warranted a need for a community-based IFA program. We presented our proposal to the local Civil Surgeon, who agreed to support our efforts. Thereafter, we mobilized Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs) from the Indian government’s Reproductive and Child Health program to distribute IFA to the brick laborers. Because the brick laborers were frequently overlooked due to their migratory patterns, we purposefully directed the intervention towards their community. The brick factories’ owners were skeptical and reluctant to implement our plan; they had heard of the side effects associated with IFA and did not want to be held liable for the laborers’ health. After much convincing, however, the brick owners granted us their permission.

With the support of government physicians and the ASHAs, we provided IFA along with deworming medication to the anemic women and children (deworming prevents parasitic infections that can exacerbate anemia) [7]. Each ASHA oversees 1000 individuals in her resident community. To ensure the brick zones had representatives who understood the IFA medication at a more local level, we selected two motivated laborers, Meena and Rakesh, to serve as community health promoters. The health promoters were given the responsibility of encouraging compliance among their peers and maintaining contact with us.

Overcoming challenges: future directions

We traveled to Charnia again in December 2013 to determine the efficacy of the health promoter system that we had implemented. Most of the brick laborers fervently believed that anemia was not a problem; we were aware that local perceptions of healthcare would be difficult to change. The brick laborers were insulted when we informed them that they were anemic. Several severely anemic pregnant women even ran away from the clinic when a local physician notified them that they had to be transported to the government hospital for further treatment. On this trip, we learned that most of the laborers had stopped taking IFA because one individual had experienced side effects. Some children had perceived the IFA to be candy and had consumed too many tablets, which caused them to also experience side effects. Other laborers simply did not want to associate with the medicine.

We realize that it will not be possible to reverse the situation in Charnia in the span of a few months, but continued efforts will eventually give rise to increased awareness and medication adherence. We have partnered with the Chandigarh Rotaract club (the youth branch of Rotary) to better ascertain the ongoing local situation with the health promoters and ASHAs, organize more community events, and potentially implement educational programs into Charnia’s schools. Educating the younger generation of Charnia would further promote sustainable change. Moreover, we have opened a clinic in Charnia with the Param Seva Trust, and we hope to use this facility as a center for health education and discussions. On our next trip, we will investigate the community’s nutritional patterns and cultural perceptions of anemia in greater depth, as well as conduct focus groups with the ASHAs.

Another plan of ours is to collaborate with The George Institute for Global Health, based at Oxford University, the University of Sydney, and Peking University Health Science Center, to bring mobile technology to Charnia. Our needs assessments indicated that nearly 80% of the brick laborers owned mobile phones. Therefore, mobile health technology could be used for compliance reminders and electronic medical records with the local Primary Health Center. As such, we need to first gauge how receptive the villagers and ASHAs would be to this type of initiative. If we receive positive feedback, we aim to provide ASHAs with a smartphone application that will help them work alongside the health promoters to target anemia and malnutrition in Charnia, and help the community members better understand their diagnoses.

The NU experience

As an undergraduate organization, we continually attempt to stay connected to Charnia while propelling our initiatives forward, organizing on-campus programming and fundraising events, finding sponsorship and networking opportunities, and promoting a sense of camaraderie within our own group. Many of our members have not yet traveled to Charnia, so they learn about it from those of us who have had the opportunity to go. Unquestionably, the key challenges that we face as a chapter are funding and communication. We strive to hold unique fundraisers that will attract donors and raise awareness about our initiatives. Also, from learning the language to maintaining contact with health promoters in India who only have access to the most basic mobile phones, our team has to constantly find novel ways to communicate with each other and the people in Charnia.

Fortunately, the first conversation I had with Manisha is still vivid in my mind. Now, I am able to enrich that memory with the experiences I have had over the past three years. To paraphrase social media visionaries Robert Scoble and Shel Israel, sometimes, the best way to understand how far something can go is to look back and see how far it has come. I am excited to see where Project RISHI heads next.

References

- World Health Survey Instruments and Related Docu- ments. World Health Organization Health Statistics and Health Information Systems. n.d. Web. 10 Feb. 2014.

- Sharman, A., Anemia Testing in Population-Based Surveys. Maryland: ORC Macro. 2005

- de Benoist, B. et al., Worldwide prevalence of anae- mia 1993-2005. World Health Organization Global Database on Anaemia, Geneva. 2008.

- Pasricha, S.R. et al., Determinants of Anemia Among Young Children in Rural India. Pediatrics. 2010. 126.1: E140-149.

- Levy, A., et al., Maternal anemia during pregnancy is an independent risk factor for low birthweight and preterm delivery. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol, 2005. 122(2): p. 182‐6.

- SRS Statistical Report 2011. Registrar General and Census Commissioner of India; Government of India.

- Iron Deficiency Anaemia, Assessment, Prevention and Control. World Health Organization. 2001.

About the Author

Varshini Cherukupalli is a senior undergraduate student at Northwestern University. She co-founded the Northwestern chapter of Project RISHI in 2011 and has served as the president since then. Varshini will be attending the Feinberg School of Medicine beginning in August of 2014. Here, she writes about her experience leading Project RISHI and establishing a relationship with their partner community in Charnia, Haryana, India.