By Sarah Jane Quillin

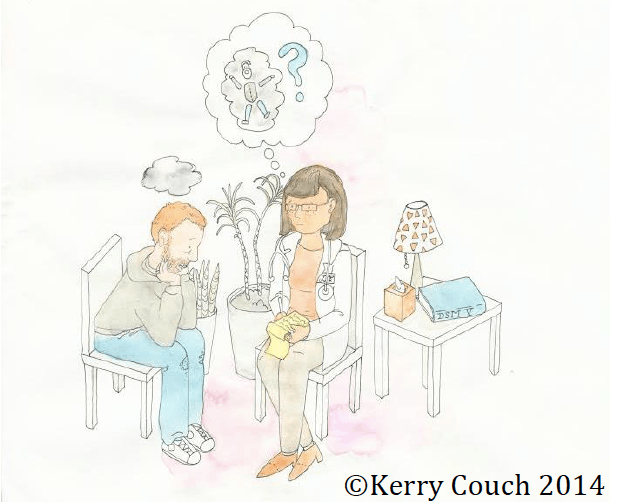

In The Book of Woe: The DSM and the Unmaking of Psychiatry, author Gary Greenberg reports on the supreme controversy surrounding the latest revision of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). The DSM, published by the American Psychiatric Association (APA), is meant to provide common language and criteria for diagnosing mental illness. Greenberg’s purpose in telling the story of the fifth edition of the DSM (DSM-5) is twofold. The author first aims to educate readers on what he regards to be a hidden truth of psychiatry. In tandem, he argues that, due to the intrinsic difficulty accompanying diagnoses based on symptoms alone, psychiatric diagnoses should not rely on diagnostic constructs like those within the DSM. Greenberg, a therapist and mental health journalist, tells the story of the DSM from its inception in the 1970s until its controversial revision over the past 5 years, using this context to make an overarching philosophical argument about how we conceptualize mental suffering. The story of DSM-5, a back-and-forth between the APA and its most prominent critics, is of interest to anyone who has suffered some form of mental distress or cared for someone who has. The story is also relevant to public health advocates seeking to understand historical and political forces behind creation of diagnostic concepts. The author compels his audience to think critically about how these concepts influence the medical decisions, as well as the identity politics, of people suffering from mental illness.

In The Book of Woe: The DSM and the Unmaking of Psychiatry, author Gary Greenberg reports on the supreme controversy surrounding the latest revision of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). The DSM, published by the American Psychiatric Association (APA), is meant to provide common language and criteria for diagnosing mental illness. Greenberg’s purpose in telling the story of the fifth edition of the DSM (DSM-5) is twofold. The author first aims to educate readers on what he regards to be a hidden truth of psychiatry. In tandem, he argues that, due to the intrinsic difficulty accompanying diagnoses based on symptoms alone, psychiatric diagnoses should not rely on diagnostic constructs like those within the DSM. Greenberg, a therapist and mental health journalist, tells the story of the DSM from its inception in the 1970s until its controversial revision over the past 5 years, using this context to make an overarching philosophical argument about how we conceptualize mental suffering. The story of DSM-5, a back-and-forth between the APA and its most prominent critics, is of interest to anyone who has suffered some form of mental distress or cared for someone who has. The story is also relevant to public health advocates seeking to understand historical and political forces behind creation of diagnostic concepts. The author compels his audience to think critically about how these concepts influence the medical decisions, as well as the identity politics, of people suffering from mental illness.

Greenberg familiarizes his readership with the complex concept of diagnosis and the difficulties associated with psychiatric diagnoses by invoking a Socratic metaphor. Describing discrete diseases requires bringing the scattered particulars of disease manifestation together into one idea that is a truthful representation of that illness. Socrates asserts that these ideas must be fashioned “according to the natural formation, where the joint is, not breaking any part as a bad carver might.” Greenberg’s main philosophical conviction throughout his book stems from this point, that “a good diagnosis must be more than the fancy of the diagnostician, more than merely deft. It must also be accurate. It must carve nature at its joints.”The author, again invoking Plato, seeks to reveal to his audience what he considers to be the hidden truth of the field, or psychiatry’s “noble lie” – that the disease constructs described in the DSM have, to date, no biological basis. To Greenberg, it is very important for readers to understand that disease constructs like Major Depressive Disorder or Generalized Anxiety Disorder, are the product of expert consensus on patient behaviors rather than hard, scientific data. Instead of using concrete, measurable biomarkers like insulin and cholesterol, clinicians diagnosing mental illness have only outward symptoms to go by, symptoms that are variable and difficult to recognize and describe. In addition, these criteria are not indicative of specific, discrete pathologies, even if accurately described. Continually harkening back to this truth throughout the story of DSM5, Greenberg makes the argument: Due to intrinsic difficulties and limitations outlined above, psychiatric diagnoses cannot and should not be medicalized, or categorized according to criteria like the constructs contained within the DSM. The author argues that in seeking to do so, the APA does more harm than good to its patients and the public at large. It is under this mindset that Greenberg reports on the latest revision of the DSM, which is, to him, “an anthology of suffering…a book of our woes.”

After the APA announced the DSM would be revised in 2008, a war of words broke out in the press between the leaders of the revision effort and their detractors, including prominent former head of the APA and leader of the DSM IV revision, Dr. Allen Frances. Throughout the years that Greenberg covered the revision of DSM-5, published in May 2013, the APA held that the DSM was in need of a new paradigm, revising diagnostic tools and criteria to improve the reliability of diagnoses. Critics like Dr. Allen Frances cautioned that the science needed to facilitate a paradigm shift simply was not there, that a revision would hurt the reliability of the DSM as an instrument of diagnosis and hurt the credibility of the APA, hurting its patients in the process.

Greenberg documents the revision of DSM-5 through three storylines: interviews with the main players on each side of the DSM-5 debate, summaries of controversy surrounding particular DSM changes that played out in the pages of the New York Times and Psychology Today, and conferences like the APA’s annual meeting. While the story-telling is rigorous and objective, the underlying tone is never unbiased. The author tells about a revision that is premature, rushed, and essentially a bureaucratic disaster. While the heavy account is cut with witty comparisons and humanizing anecdotes, the underlying tone is dead serious. The author tells bluntly, with conviction, how a bungled revision will negatively affect the identity politics of countless numbers of patients. At his most critical, Greenberg points out the myriad of other incentives the APA has for publishing a new DSM: pharmaceutical money, publication money, and an attempt to maintain the credibility of the profession. Although often derisive, the author is respectful; asserting that he, the APA, and its major critics all genuinely want to treat patients and help people.The philosophical and personal nature of the writing compels the reader to care about how changes are made to the manual used to diagnose our suffering. The Book of Woe is accessible, addressing specialized topics like epidemiological study design colloquially. The author is particularly adept when illustrating the difficulty of psychiatric diagnoses through backstory on the controversy surrounding specific disease constructs like Major Depressive Disorder or Asperger’s Syndrome. Greenberg’s telling of the DSM-5 revision sincerely opens a public conversation on a subject that few authors, historically, have approached with such depth and detail.

One criticism against the message of the book itself comes from the book’s champion and prominent DSM-5 critic, Dr. Allen Frances. While Frances and Greenberg agree the DSM constructs are flawed and the revision was mishandled, they are not in agreement about the medical model of psychiatry. Frances believes that the manual, though flawed, is the best option psychiatry has, and that option is better than nothing. In an interview described within The Book of Woe, he warns Greenberg against defaming the DSM and exposing the “noble lie,” lest his words wrongly convince patients successfully receiving help to go off medication or refrain seeking help to start. This is a valid, poignant argument, one concerning grim realities for patients. Greenberg responds, somewhat tersely, as he has in past interviews: he believes the potential for harm caused by the DSM far outweighs potential public health risks generated by The Book of Woe. At near 350 pages, it would have been more satisfying to the reader to have this point addressed in more depth.

While the author presents a compelling, heartfelt argument, the reader is left with practical questions. Negative consequences of the use of the DSM may include suffering incurred by patients subjected to psychiatrists changing diagnoses, pathologizing normal behavior, or overprescribing medication. Our healthcare economy, however flawed, is a reality in which patients suffering from mental illness must seek care. The system requires a method for disease categorization to ensure reimbursement from insurance companies, and that current method is the DSM. While Greenberg seeks only to make a strong argument in his book, and not solve this practical problem, his account still raises the practical question: If not DSM, then how? Any major rethinking of the psychiatric field must adhere to these practical limitations. By the end of the book, whether one agrees with Greenberg’s overarching argument or not, the story of DSM-5 leaves its reader wiser, and more concerned, if not somewhat shocked. The author writes with the genuineness of a journalist who truly believes in the gravity of their message.

The Book of Woe was published in January 2013 by Blue Rider Press of Penguin Publisher’s group.

About the Author

Sarah Jane Quillin is a PhD/MPH candidate studying microbiology in Dr. Hank Seifert’s lab. Her research interests are infectious disease epidemiology, antibiotic resistance, and the way laboratory research affects public health policy.