(co-authored with Katherine Amelia Conte and Jaime Dominguez)

Chicago’s political order was upended in last week’s mayoral primary ushering in a historic and potential new era in Chicago’s racially polarized landscape and vaunted Democratic political machine. First, two black women, former federal prosecutor Lori Lightfoot and Cook County Board President Toni Preckwinkle, will face off on April 2nd. Chicago has had one woman and two black men serve as mayor, but whoever wins the runoff will become the first black woman to be chief executive of a government of more than 2 million in American history. This is an historic milestone, and the landmark is part of a broader overall shift in America’s big-city politics in which the interests of citizens matter as much as the interests of the cities themselves.

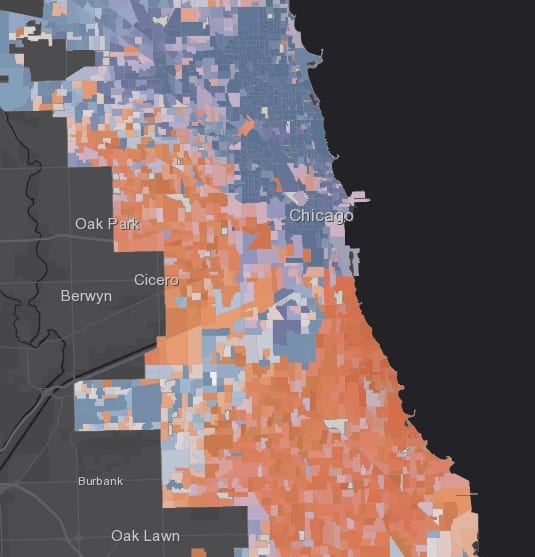

Map: Check our map to examine the fine-grained results for yourself here.

The primary election revealed an undercurrent of anti-establishment sentiment growing among voters and an electorate up that still is up for grabs. The fact that two-thirds of the electorate did not vote for either of the candidates to make the mayoral run-off (and two-thirds of registered voters stayed home entirely) presents a series of opportunities and challenges. For example, seven different mayoral candidates came in first in at least one ward yet, no one candidate got a majority in any ward. Not even Bill Daley could secure the vote in the 11th ward, home to the Daley family dynasty.

So, what does this tell us about election going forward? It will be a battle of self-styled progressives. On the one hand, as an outsider centered on reeling in corruption and bringing ethics reform to the city, the political winds that swept up the city council could favor the Lightfoot campaign. She is in a position to win over the progressive bloc to support institutional reform, police accountability and neighborhood investment. As for Preckwinkle, an insider closely tied to the Democratic political machine, she may have to work harder to win over the new city council members who have run against the organization. However, her bread-and-butter issues of a increasing the minimum wage, providing affordable housing and criminal justice reform might be the platform that could win over the undecided including the new city council.

Regardless of who prevails, the next mayor and City Council faces a financial albatross such as an extra $270 million in public employee pensions next year, a figure that is expected to balloon to $1 billion by 2023. These fiscal ills with the looming education crisis makes governing a daunting challenge. Most urgently, the city has been unable to provide the basics of public safety. Violent crime rates remain far too high, which may complicate the reforms required to address a long record of police misconduct.

Voter turnout was about average for Chicago at 35% but lower among Chicago’s restive millennials, the group that has most visibly been driving the push for reforms lately. Early results show that whoever wins in April, they will be tested by a newly emboldened progressive City Council. Progressive unions and activists have already succeeded in electing three new representatives. And, in 14 other aldermanic races, there will be a runoff against 10 Emanuel-leaning incumbents because neither was able to garner more the 50 percent of the vote. The United Working Families is one organization leading this charge for change. In fact, 8 of their endorsed candidates either won outright or advanced to the runoff on April 2.

The only certainty is uncertainty

Beyond these firsts, the apparent chaos of the mayoral election marks a break from the orderly past. This week’s election was totally unpredictable. With several candidates polling in the teens and none ahead of the pack, figuring out which two would advance to the runoff in low-turnout election on a blustery February day was statistically akin to rolling two dice. In 2007, Richard M. Daley won every ward in the city on the way to his final term in office. Tuesday, seven different candidates came in first in at least one ward, and no candidate got a majority in any ward, even a Daley in Bridgeport. These results meant that Preckwinkle and Lightfoot advanced, even though their combined vote share was only 33 percent.

Where will the other 2/3 of voters turn in the April run-off? A closer look at this chaos suggests that the second round will be as unpredictable as the first. One curious result made possible by the divided field is that each of the leading candidates tended to do better in the same parts of the city—the historically reform-minded areas around Hyde Park and on the lakefront wards of the North Side.

(Related: CDP’s Kumar Ramanathan takes a closer look at this unusual outcome here)

What of the other lanes? Neither candidate did particularly well in the largely white bungalow belts on the city’s edges, which went to Daley and newcomer Jerry Joyce. This is a non-change, and not particularly surprising—the more conservative areas of white Chicagoans have always been “reluctant” to support candidates of color, and two Latinx candidates (Gery Chico and Susana Mendoza) were in the lead on the city’s Southwest and Northwest sides (on the other hand, support for Lightfoot and Preckwinke was not strongly correlated to racial demography overall—that itself is a noteworthy departure from Chicago’s past). A bit more surprising was that Preckwinkle and Lightfoot ran behind the self-funding businessman Willie Wilson in the predominantly African American wards of the South and West sides. Mendoza, Chico, and William Daley’s successes seem more or less attributable to conventional politics, so working with those leaders to bring their organizations on board may be a promising strategy for the run-off participants. Voters who went for the surprisingly successful self-funding candidates (Joyce and Wilson) may be more unpredictable and perhaps alienated from the conventional politics of the moment. We’re about to see a month-long bridge-building contest between Lightfoot and Preckwinkle to connect with voters in these areas.

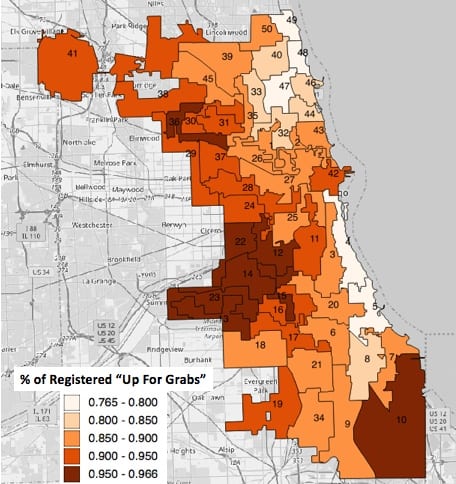

Chicago has only had one mayoral runoff before, in 2015. Then, turnout increased by 7 percentage points from the first round to the run-off. This change was driven primarily by mobilization in Chuy Garcia’s stronghold on the Southwest side, a result that narrowed Emanuel’s eventual victory considerably. This time, the change between now and April 2 is even more uncertain. When we count up the potential voters up for grabs (ie, registered voters who either did not turn out last week or who supported a candidate who didn’t make the runoff) in this election, the main thing to take away is uncertainty. In many wards, more than 90% of registered voters fall into that group:

In other words, there are plenty of votes still on the table–but who is best positioned to scoop them up?

As head of the Cook County Democratic Party after decades on the Chicago electoral scene, Preckwinkle is more connected to the organized political forces that might help her mobilize some of the more organize-able parts of the city. But the unfolding and layered scandals of this fall, rippling out from indictment of longtime party elder Ald. Ed Burke (that indictment cost about Burke 30 points in his own re-election campaign, but not his seat), make organizational ties more of an albatross to be minimized than an asset to be advertised. In an “onward-to-the-runoff” speech Tuesday night, she even disingenuously tried to characterize herself as the remaining outsider in the race. Despite her place in the city’s party establishment, Preckwinkle was endorsed by the Chicago Teacher’s Union and SEIU, groups who have become the effective local opposition party in recent cycles. Such groups provide progressive bona fides and are an important resource for persuasion and mobilization—but why didn’t they get her more than 16 percent this time? Lightfoot’s background as a reformer and lack of electoral-politician experience may come as an asset here; and because her base in relatively more affluent areas, her supporters may be more prone to turnout without substantial mobilization or organization. As in national politics, this election has developed a distinctive outsider-insider dimension, rooted in corruption fatigue, that sits alongside more longstanding divides on ideology, identity, and policy.

Part of a national trend

This brings us to the broadest insight we can draw from this crowded-field contest, about the state of big-city politics today. In the decades since the “urban crisis” of the 1970s and 80s, America’s big cities have largely rebounded, but they have also operated within a narrow policy agenda focused on the abstract fiscal health of the city—which usually emphasizes competing for business investment and providing amenities for the wealthy before the day-to-day concerns of city-zens. This has led to a managerial centrism in government even in some of the most overwhelmingly liberal cities in the nation, a status quo that is being upended.

In 2013, New York city’s mayoral election had a similarly fractured field. Five high-profile candidates ran in a Democratic primary that sounded like a progressivism contest in response to the policy agenda of the outgoing Bloomberg administration, which focused less on neighborhoods and services than on attracting outside investment. Bill De Blasio won that primary, powered by the emergence of a “brownstone bloc” of ideological liberals in politically engaged, gentrifying or gentrified areas in Brooklyn and the Upper West Side. He also garnered organizational support and ideological-street cred from the Working Families Party, a coalition pushing for social welfare policies—affordable housing, living wages, and decriminalization of non-violent conduct.

Something similar is happening in Chicago, as local grassroots groups were quite ebullient at the results at the mayoral and aldermanic level. There is a sense that under Daley and Emanuel, many Chicagoans have had to take a back seat to an imagined “Chicago” that is increasingly distant from their own experiences. In an interview the week before the election, William Daley argued that the mayor’s job is to be the city’s chief salesman, aiming to emphasize a business-friendly environment. His background suggested an almost too-perfect vision of continuity with the current regime, and both his brother and Emanuel had won the last 8 mayoral elections on a similar platform and record. This time, that agenda got 14 percent of the vote, displaced by a vision of using the city’s resources toward more inclusive ends. Whether this alternative vision–which is fragmented and contested, if the highly divided electorate is any indication–can actually be implemented, or will bog down in the hyperpluralism that can emerge when a machine loses, remains to be seen.

You must be logged in to post a comment.