Results and Responses

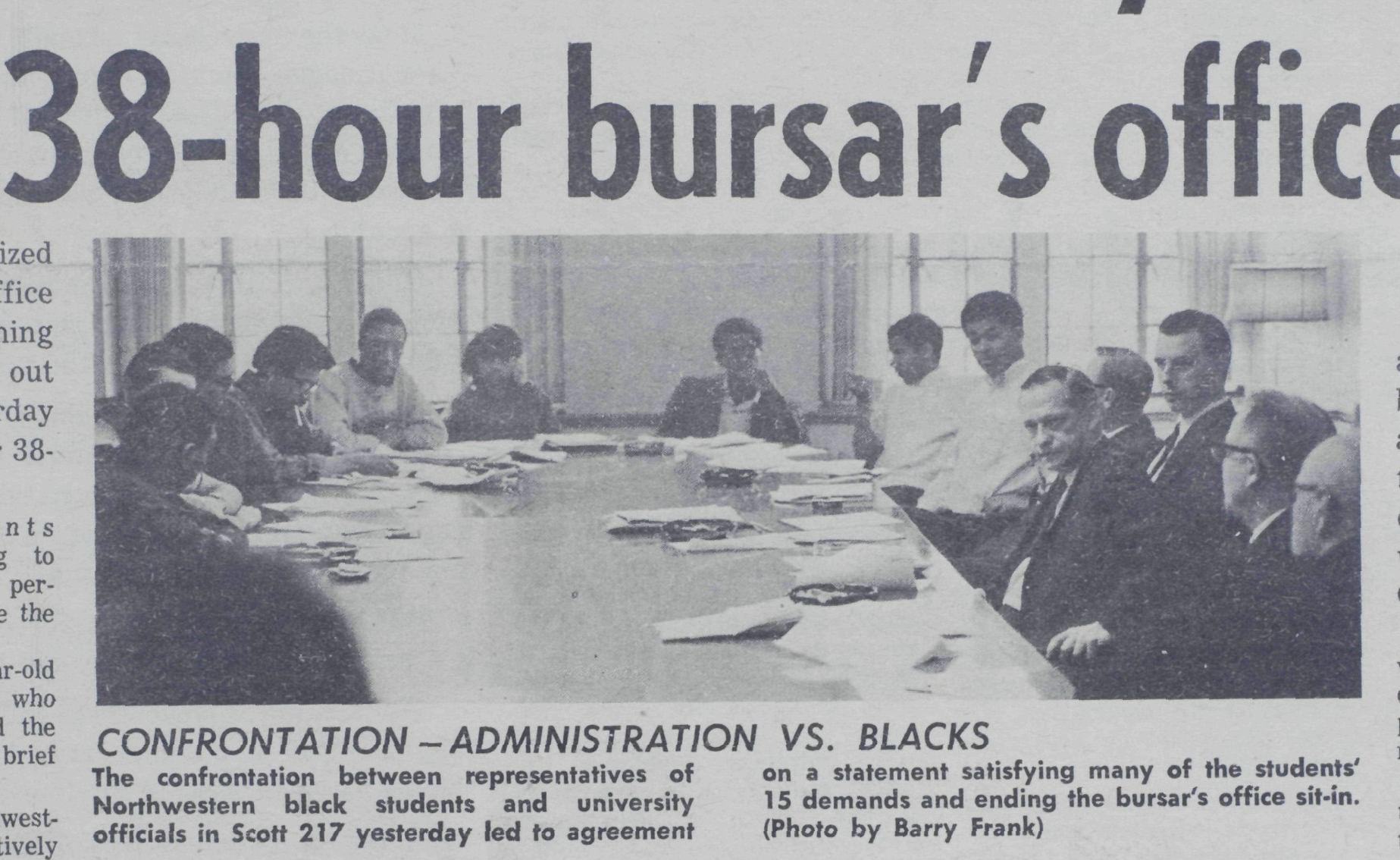

Representatives of FMO and AASU meet with members of the administration to discuss the terms of the “May 4th Agreement.”

On Saturday, May 4, 1968, at 9:00 a.m., representatives from For Members Only (FMO), the Afro-American Student Affairs (AASU), and the Northwestern administration convened in Scott Hall Room 217 to negotiate an agreement to end the takeover of the Bursar’s Office. Student representatives included James Turner, Kathryn Ogletree, Amassa Fauntleroy, John Bracey, Victor Goode, Vernon Ford, Roger Ward, Michael Smith, Harold Daniels, and Arnold Wright. Representing the administration and faculty were Payson Wild, Franklin Kreml, Robert Strotz, William Ihlanfeldt, Joe Park, Lucius Gregg, Gail Inlow, Robert Baker, Walter Wallace, and Roland Hinz.

By 5:00 p.m., both parties finalized the terms of what is now known as the “May 4th Agreement.” The agreement established multiple advisory committees, comprising FMO members and administrators, to guide improvements in admissions, financial aid, and open housing. Northwestern also committed to setting aside designated living units for Black students, providing a campus location for a Black student union, and expanding the academic curriculum to include African American Studies.

Evolution of the Demands to the May 4th Agreement

|

Demand |

Demands, April 22 | Demands, April 26 | May 4th Agreement |

| Policy Statement |

A Northwestern University official present an official statement acknowledging the existence of institutional racism at the University, and denouncing future tolerance of racism

|

President Miller issue a public statement of zero tolerance of racism at Northwestern University Restructure the University Disciplinary Committee (UDC), or create a new judiciary board to address racial incidents Retroactively apply this practice to the April 15 decision regarding Sigma Chi Fraternity Black students approve all appointments to the Human Relations Committee, or at least 50%

|

Granted: The administration will issue an official announcement deploring racism Establish an advisory council consisting of 10 Black students, chosen by the University from a list of 20 nominees presented by Black students; they will consult the University on approaches to being more responsive to the needs of black students, recommend changes in university procedures, support in the selection of University committee on Human Relations; these are salaried positions Not granted: Black students approve all appointments to the Human Relations Committee, or at least 50% |

| Admissions |

Guarantee the gradual increase of Black students to Northwestern, at least 12% Create a project to recruit Black students to campus Include Black students (of their own choosing) to advise on the steering committee for admissions At least 50% of incoming Black students come from inner city schools The administration present a list of Black students enrolled at the University

|

Guarantee the gradual increase of Black students to Northwestern, 10-12% Provide incoming students with enough financial aid that attending is actually feasible Include Black students (of their own choosing) to advise on the steering committee for admissions; these should be salaried positions; these representatives have shared power with the Office of Admission and Financial Aid in making all decisions relevant to Black students, including Black students admitted At least 50% of incoming Black students come from inner city schools The administration present a list of all Black students enrolled at the University and incoming students, with contact information to FMO Arrange a meeting between FMO and incoming Black students

|

Granted: Appoint a committee of Black students to assist the Admission Office in recruiting Black students to campus; salaried positions Seek to enroll 50% of Black students from inner cities, but not a guarantee Provide FMO with a list of the names and contact information of Black students Allocate funds for Black students to organize an orientation for incoming Black students Not Granted: Assuring that at least 10-12% of Black students are represented in each incoming class Giving student representatives shared power with the Office of Admission and Financial Aid in making all decisions relevant to Black students, including Black students admitted

|

| Financial Aid |

Increase scholarships for students to supplement the need for work-study Offer financial aid for summer school |

Offer special consideration for increasing financial aid for Black students Include Black students (of their own choosing) to advise on the steering committee for financial aid Eliminate student loans and work-study; replace them with scholarships

|

Granted: Appoint a committee of Black students and faculty to advise the Financial Aid Office on policy matters regarding financial aid to Black students Provide financial aid for the summer session |

| Housing |

Provide living units for Black students who want to live together by fall 1968

|

Provide living units for Black students who want to live together by fall 1968; or get rid of fraternity/sorority houses

|

Granted: Reserve a separate living unit for Black students

|

| Curriculum |

Offer Black Studies courses and hire Black professors

|

Immediately offer Black Studies courses and hire Black professors Create a visiting professor chair of Black Studies; allow Black students to select this individual each year |

Granted: Add Black Studies courses to the curriculum Follow-up procedures go through the Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences; they will recommend degree requirements Black students are asked to recommend specific courses and potential faculty Not granted: Black students to select faculty of Black Studies

|

| Counseling | Hire a Black counselor, someone who can relate to Black students and help them cope with stressors associated with being on a predominately white campus |

The University had already hired a counselor, but not of the student’s choosing Going forward, Black students must approve the hiring of a counselor

|

Granted: Allow Black students to approve of personnel hired as counselors of Black students |

| Student Union |

Allocate space on campus for Black students to have for social and recreational purposes It will serve as a space for the student organization For Members Only (FMO)

|

This demand was granted |

Granted: Provide a space on campus for a Black student union |

| Open Occupancy | Students recognize that the University supports open housing; they want the University to present evidence of this to the president of FMO to verify that their stand is genuine |

Students want the University to demonstrate greater involvement in upholding the Evanston Open Occupancy Law Students want to be part of the committee reviewing the study of open housing in Evanston |

Granted: Allow Black students to participate in open housing review committees and to work with the administration on new housing policies for the University |

Announcements of the "May 4th Agreement"

At 8:00 p.m., Dean Hinz announced to the press that Northwestern and representatives from FMO and AASU had reached an agreement. He also made a public statement acknowledging the broader issues of institutional racism: “We cannot be complacent with institutional arrangements that ignore the special problems of Black students. An important and difficult problem is that of an essentially white leadership coming to understand the special needs and feelings of the Black students, as well as the difficulty arising because the Black student does not regard the white university authorities as capable of appreciating all of the nuances of his decidedly separate culture.”

Following the announcement, Dean Hinz and other administrators inspected the Bursar’s Office and found no evidence of property damage, a reflection of the students’ intention to avoid misrepresentation during the demonstration. By 9:30 p.m., the remaining Black students exited the building, officially ending the 38-hour occupation. The campus community marked the conclusion of the protest with a celebration. Students joined members of FMO and AASU in song, including renditions of “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” the Black national anthem, and the civil rights anthem “This Little Light of Mine.”

James Turner also spoke to the press:

“The situation at Northwestern University has been positively resolved. To this extent it is to the benefit of all concerned and to the general community. The difference between this situation and the one at Columbia was due to the enlightened manner in which the administration conducted its response. They displayed themselves as men not only of responsibility but with a willingness to listen and learn.”

On May 9, 1968, Turner continued the conversation during Northwestern’s Student Symposium 1969, where he spoke on the topic “Black Students: After the Crisis.” The event was broadcast on Northwestern’s student radio station, WNUR. Selected audio clips from Turner’s address are featured below:

|

Turner discusses the work ahead to implement the “May 4th Agreement.” He also responds to backlash and criticisms of the Takeover (00:06:57). |

Turner outlines the reasons students organized the Takeover, particularly addressing issues of social alienation and the importance of Black students having their own spaces on campus (00:06:14). |

Turner discusses the problems associated with advocating for a color-blind approach to correcting racism (00:05:44). |

Reaction

Although the administration and Black students reached a peaceful and productive resolution, responses to the Bursar’s Office Takeover were mixed across the university community and broader public. The press closely covered the 38-hour demonstration, with some outlets offering balanced coverage of both the protest and its resolution. However, the Chicago Tribune published a disparaging article referring to the event as a “chitlin revolution,” invoking a racial stereotype. The article also criticized the administration, claiming it “gave in” to the student’s demands. While many faculty members had not initially supported the Takeover, the Tribune’s rhetoric offended a number of them, prompting several to write letters to the editor in defense of the administration’s response to the protest. Ultimately, 425 of Northwestern’s 734 full-time faculty expressed support for the outcome of the May 4th Agreement.

President J. Roscoe Miller, though critical of the student’s methods, acknowledged the legitimacy of their concerns. In a public statement , he admitted that the Univeristy had “failed to understand the depth of the problems presented by prior petitions.” The Board of Trustees, however, expressed greater hesitation. Rather than immediately endorsing the May 4th Agreement, the Board appointed a subcommittee to investigate the circumstances surrounding the protest. Some faculty members, frustrated by the delay, submitted letters to the Board. On May 12, 1968, the Board approved a resolution affirming the May 4th Agreement and authorized the administration to proceed with its implementation. At the same time, the Board condemned the students’ tactics as unlawful and disruptive and advised the administration to take preventive steps against similar actions in the future.

The Alumni Board echoed the President and Board of Trustees in disapproving of the protest methods. Nevertheless, on May 7, 1968, Alumni Association President Howard Rosenheim issued a statement supporting the administration’s handling of the situation: “The students on campuses today are challenging the values and standards of our society as never before. In some cases, they are employing extreme methods to gain their ends. When the dust is settled and we look to the deeper meaning of the actions at Northwestern, I believe we will find a source of pride and hope for the future.” Individual alumni reactions varied widely. The Alumni Relations Office received nearly 900 letters by September 1968, with approximately 225 letters supporting the University’s response and 615 expressing disagreement.

Implementation

In the days following the Bursar’s Office Takeover, administrators and Black student leaders began working to implement the terms of the May 4th Agreement. Some actions were addressed swiftly, for instance, the administration provided FMO with a list of enrolled Black students. Other demands, however, required extended timelines and prompted debate between students and administrators over strategy and pace. Despite occasional disagreements, both parties remained committed to fulfilling the agreement.

To support the new responsibilities outlined in the May 4th Agreement, particularly student participation on advisory boards, FMO restructured its leadership to create a more formal and functional organization. They introduced roles such as Governor of Campus Affairs, Correlator of Communications, and Minister of Communal Affairs, positions that provided the group with a clearer internal structure.

One significant outcome of the agreement was the allocation of a dedicated space for a Black student union. The administration initially designated 619 Emerson Street for this purpose. Students named the space the Black House, but advocated for relocation to a building with more space and improved amenities. In 1973, the Black House moved to its current location at 1914 Sheridan Road. This three-story building became the central hub for Black student life, housing FMO, Black fraternities and sororities, the Garvey-Shabazz Library, with its collection of tapes, films, and books on Black history and culture, and the Paul Robeson Conference Room. The Black House also showcased murals, drawings, and quilts created by students, as well as purchased artwork by notable artists such as Africobra, Varnette Honeywood, and Chicago-based Margaret T. Burroughs.

In 1971, the University established the Department of Minority Affairs, later renamed the Department of African American Student Affairs (AASA), to oversee support services for Black students. AASA provided academic advising, career counseling, personal support, cultural programming, and advising for student organizations.

Another major achievement was the creation of an academic department dedicated to the study of the Black experience. On March 6, 1969, the College of Arts and Sciences approved a motion to establish the Afro-American Studies program, which was later renamed African American Studies. The department officially launched in 1972, offering courses such as Afro-American History and Culture, History of Afro-American Thought on Africa, and History of Black Nationalism in America. Students advocated for the appointment of Lerone Bennett, editor of Ebony and Jet magazines, as the department’s first chair. He served in the role briefly during that formative period.

Legacy

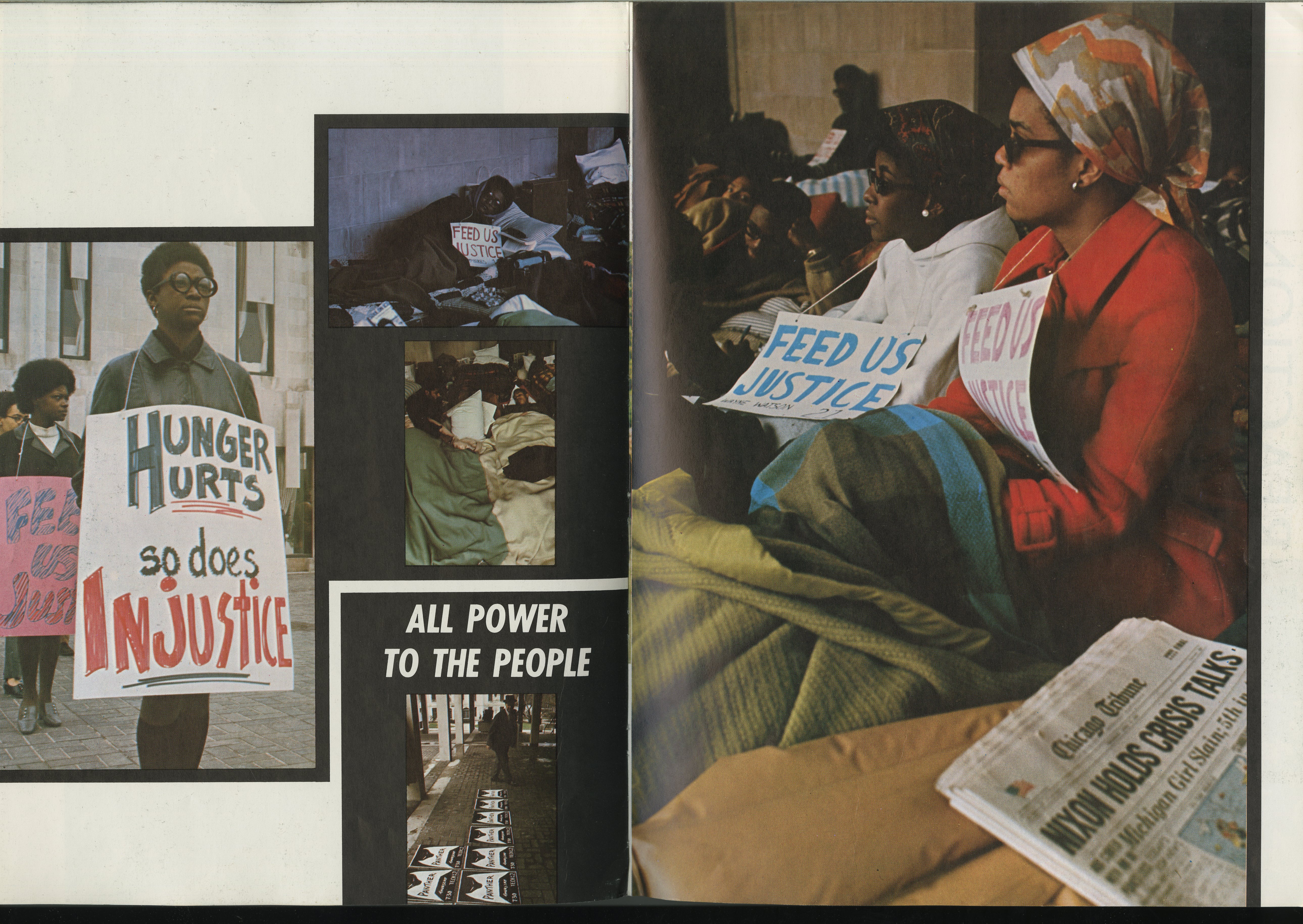

Hunger strike demonstration in front of the Rebecca Crown Center, 1969. Photo courtesy of Syllabus 1970

The Bursar’s Office Takeover was a powerful moment of collective action that demonstrated to Black students their ability to bring about meaningful change on campus. That sense of empowerment carried into the following year when students mobilized in response to the Triangle Fraternity Incident. Twenty-one Black male students, some of whom had participated in the Takeover, were charged with unlawfully entering the Triangle Fraternity House while searching for a fraternity member they believed had assaulted a Black female student. A physical altercation ensued, leading the University Discipline Committee (UDC) to issue penalties: restitution for damages and academic suspension for the year.

This decision prompted Black students to question whether the University was upholding the spirit of the May 4th Agreement in understanding the social climate on campus. In protest, students staged a hunger strike and rallied at Rebecca Crown Plaza. Despite these efforts, the UDC did not reverse its ruling.

Still, the impact of the Takeover was profound and enduring. Black student enrollment increased significantly in the years that followed, reaching 650 students, 10% of the undergraduate population, by 1973. The University began conducting periodic reviews of the Black student experience, using surveys to assess program and identify ongoing needs.

FMO also ensured the legacy of the Takeover would be preserved through storytelling and tradition. In 1969, the organization created “The Ritual,” a performance reenacting the events of the Takeover for new students during Black student orientation. The history of the demonstration has been documented in FMO student handbooks and featured in Blackboard magazine. FMO also organized commemorations and a week of activities during “Indestructible Black Consciousness Week,” keeping the memory of the Takeover alive across future class years.

The Takeover has also served as an inspiration for future activism at Northwestern. In 1986, students held a demonstration in front of Kresge to demand stronger support for the African American Studies Department. In 1995, a hunger strike was launched to advocate for the establishment of an Asian American Studies Department. In 2015, students issued a list of demands addressing issues of marginalization on campus, including student spaces, academics, faculty & staff diversity, student safety, and ethics.

The Bursar’s Office Takeover continues to resonate at Northwestern. Its legacy lives on in student activism, institutional change, and the enduring pursuit of equity and justice.

Sources

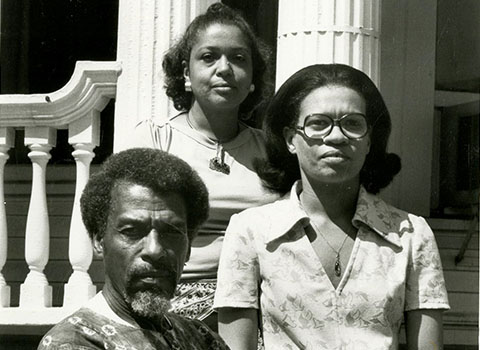

Visit the Bibliography page for sources consulted in this essay. Interviews were also conducted with the following Northwestern University alumni, Clovis Semmes, Herman Cage, Kathryn Ogletree, Leslie Harris, Jean Semmes, and James Pitts.