Why Students Made Demands

While Northwestern University has been known for offering an exemplary education to its students, it was not always considered a safe space for its entire student body. There were fundamental structures and policies that prohibited Black students from fully participating in all aspects of campus life. There are accounts of racial discrimination experienced by Northwestern’s first Black students dating back at least since the turn of the 20th century. For instance, Black students were refused entry into swimming pools, rejected from participating in Greek activities, and denied from on-campus housing; they also experienced being in a space where blackface minstrelsy was an acceptable part of campus culture. These are a few examples of the racial injustices that Black students experienced on campus. On May 3, 1968, Black students occupied the Bursar’s Office and intentionally “disturbed the serenity of college life.” They sought a sense of belonging on a campus and demanded that their University value them as respected and recognized members of the Northwestern community. They wanted their university to serve as a space where they could excel academically and attain a sense of belonging and safety on campus. The 1968 demonstration was a response to a culmination of injustices and a long struggle for Black students seeking inclusion and equality.

NU Black Student Enrollment to 1969

5Prior to 1966, on average, 5 Black students enrolled in each incoming class.

54In 1966, the first year the NUCAP program was introduced, 70 Black students were accepted to NU, while 54 enrolled in the fall of 1966.

70After the Takeover, 120 Black students were accepted to Northwestern University, while 70 enrolled in the fall of 1968.

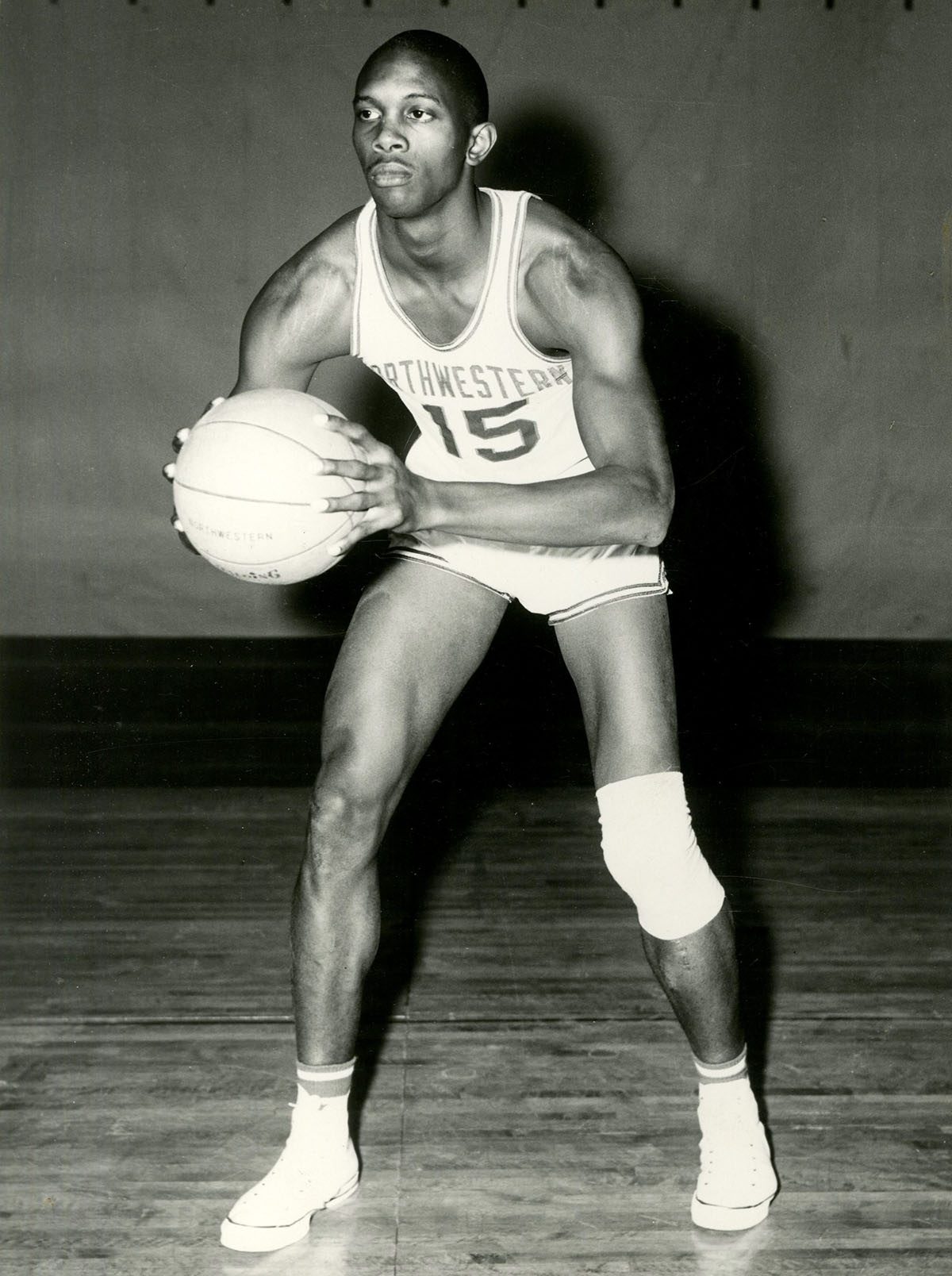

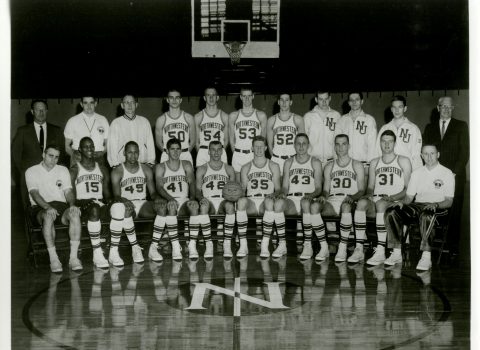

Historically, Northwestern University maintained a small and selective Black student population. Prior to 1966, each incoming class included an average of five Black students, most of whom were male athletes on scholarship. In 1961, for example, 80% of the 25 Black students were male athletes. This narrow profile shaped assumptions about who belonged on campus. Herman Cage, a 5’3″ business major who entered Northwestern in 1965, was often mistaken for a football or basketball player despite having no athletic involvement.

The enrollment of Black women was even more limited. When Eleanor Steele entered the university in 1964, there were only four Black women enrolled. Steele-Stewart recalled that some of her female peers experienced social isolation. The gender imbalance also contributed to a limited dating pool for Black students. Many Black women maintained relationships from back home. At the same time, social taboos made it unacceptable for Black men to date white women, compounding the sense of isolation for many students.

A major factor behind the demands made by Black students in 1968 was the shifting landscape of Black student enrollment at Northwestern University. In the wake of federal legislation aimed at increasing diversity in higher education, colleges and universities nationwide began recruiting students from historically marginalized communities, including Black, Catholic, and Jewish populations. The Higher Education Act of 1965, part of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s Great Society domestic agenda, sought to address systemic barriers to access by promoting educational equity and expanding financial aid. As a result, institutions like Northwestern launched targeted recruitment efforts to enroll so-called “non-traditional” students, particularly from urban centers. While these initiatives increased the presence of Black students on campus, they did not ensure the structural support or inclusive environment necessary for their success, prompting calls for institutional change.

To support the transition of incoming Black students, Northwestern developed the Northwestern University Chicago Action Program (NUCAP), later named Summer Academic Workshop (SAW). The program aimed to prepare students for the academic rigor of university life and to expose them to cultural experiences such as plays, operas, and classical music performances at venues like Ravinia. For students who were not from the Chicago area, a similar initiative called Project Upward Bound (PUB) provided comparable support. While some NUCAP participants valued the academic preparation the program offered, others criticized it for attempting to “acculturate” them, promoting assimilation into white, middle-class norms and for operating on presumptions about Black students’ backgrounds. Sandra Hill, a member of the 1966 NUCAP cohort, recalled being told she was “culturally deprived” and therefore would benefit from the program, an assessment she found both inaccurate and offensive. Another ’66 participant, Leslie Harris, noted how program leaders made board assumptions about the cultural exposure of Black students. For example, during a group trip to a play, some students were already familiar with the production, so much so that when an actor forgot their line, the students filled them in from memory. The irony of labeling these students “culturally deprived” was unmistakable. Despite its flaws, NUCAP played a key role in increasing access to Northwestern, resulting in the enrollment of 54 non-athlete Black students in the fall of 1966.

Although the increase in Black student enrollment marked a significant step toward greater representation of students of color on campus, it quickly became apparent that the university lacked the infrastructure to adequately support these students in a predominately white environment of 8,700 students. This disconnect led to a heightened awareness of racial isolation, systemic inequities, and cultural insensitivity on campus, laying the groundwork for future student activism.

Black students individually brought their concerns to university administrators, but these complaints rarely led to meaningful change. Some Black students chose to transfer to other institutions due to the disheartening social climate on campus. Leslie Harris, a freshman in 1966, considered dropping out because of the pervasive hostility and social isolation he faced. In a moment of vulnerability, he confided in a friend from home, a high school dropout, who told Harris that seeing him attend Northwestern had inspired him to return to school. Encouraged by his friend’s words, Harris decided to stay.

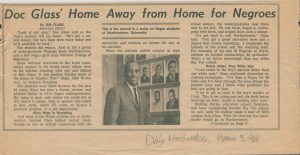

Despite their experiences of racism and alienation, Black students found support through networks of campus staff, trusted faculty, and members of the Black Evanston community. Black janitors, security officers, and domestic workers often looked out for these students and encouraged them in their studies. One of the most beloved figures was Charles “Doc” Glass, a janitor at Evanston City Hall and an unofficial recruiter of Black athletes to Northwestern. He and his family opened their home to Black students at Northwestern, as well as students from Kendall College and the National College of Education. Eleanor Steele Stewart referred to the Glass home as a “home away from home” for Black students.

Leslie Harris also found mentorship in graduate students Sterling Stuckey and Jim Pitts, as well as fellow undergraduate Amassa Fauntleroy, who helped Harris start the Afro-American History Club. This integrated student group brought guest speakers to campus to lecture on Black history and culture, including Lerone Bennett, editor of Ebony and Jet Magazines.

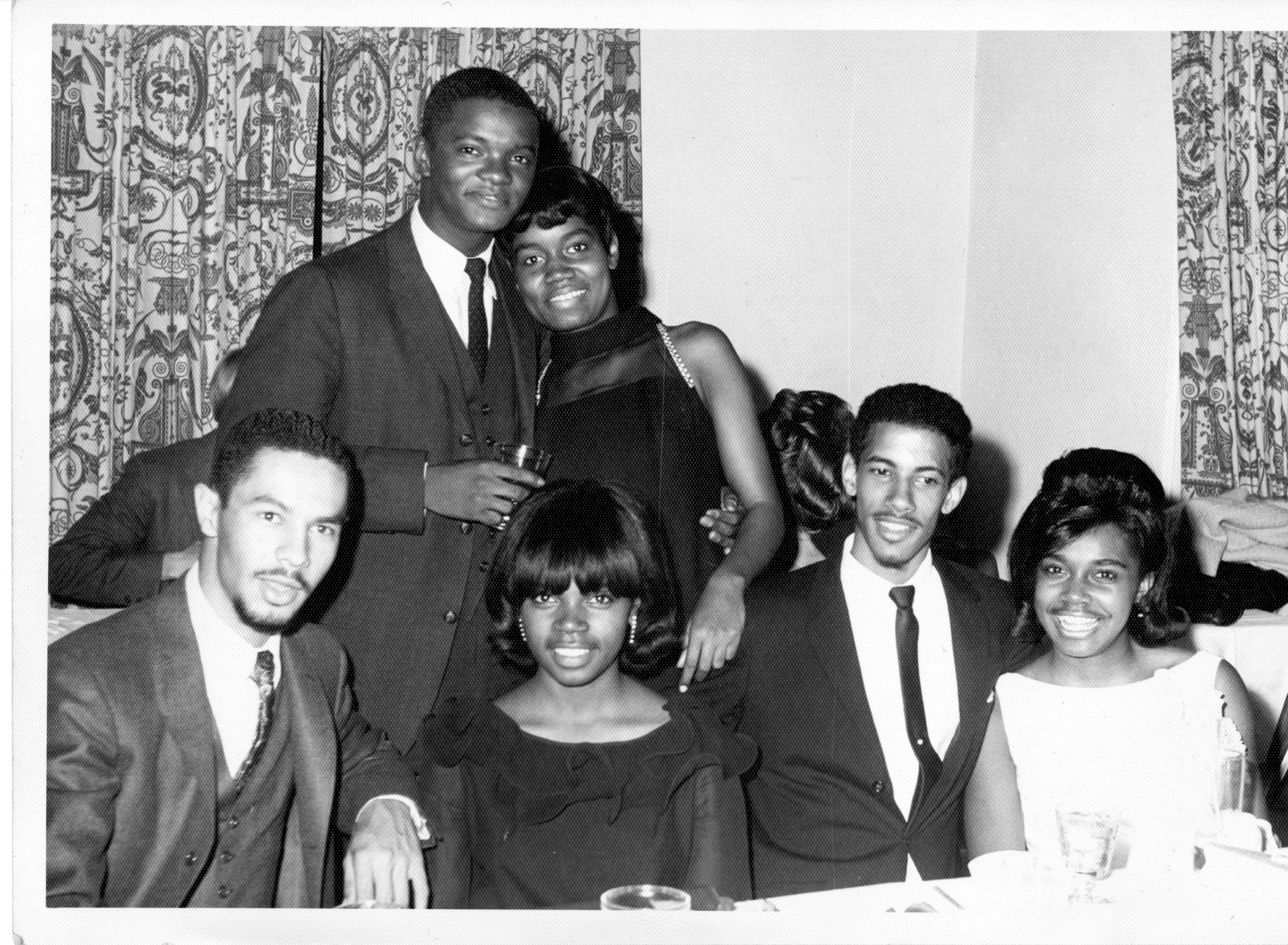

Alpha Omicron Pi sorority dance for new inductees, (fall 1967 or winter 1968). Seated left to right: Victor Goode, Diane Hinton (sister of Audrey Hinton, visiting from college), Michael Smith, Audrey Hinton. Standing: Lonnie Terry and Detra Smith. Photo courtesy of Audrey Hinton.

In addition to informal networks, Black students also established a formal support system of their own. During the summer of 1967, Herman Cage, a junior, was struck by a sign outside of a local country club that read, “For members only.” The sign’s message of having an exclusive space resonated with him. It underscored the need for Black students to have a space of their own, an organization that could advocate for their needs and foster community. Additionally, as the number of Black students increased, it became clear that support from individuals like “Doc” Glass alone was no longer sufficient.

Toward the end of the second NUCAP session in summer 1967, NUCAP counselors Herman Cage, Jim Pitts, Wayne Watson, and Vernon Ford formed For Members Only (FMO). When students returned in the fall, FMO welcomed incoming Black students with an orientation, offering advice on navigating their first year and stressing the need “for Black students to organize for their collective survival and growth in a hostile environment.”

In Ebony’s May 1968 article “Confrontation,” incoming student Barbara Butler shared, “this group has reaffirmed my identity as a Black person. I came from a suburb in Virginia, and I didn’t know anything about me or my people. This group hit me in the face—my reality as a Black person. And now it’s like a juice to me, my life blood.”

FMO intentionally chose not to seek official university recognition, wary of potential repercussions. Instead, they sustained themselves through membership dues and elected leadership, with Herman Cage as its first President, and first-year student Kathryn Ogletree as Vice President.

At the time, Jim Pitts was a graduate student in sociology who documented the shift taking place among Black students at Northwestern. He argued that they were developing a collective race consciousness as they sought to understand their experiences in a predominantly white environment. They hosted lectures, attended off-campus conferences, and organized events with students from other predominantly white institutions.

In fall 1967, sophomore Daphne Maxwell, was crowned Northwestern’s first Black homecoming queen. A campus newspaper later suggested she “felt small” for not having an escort during the ceremony. Milton Gardner responded on behalf of FMO rejecting that portrayal. This moment was emblematic of the broader shift, Black students were becoming increasingly vocal about their representation and the racial dynamics on campus. FMO served as a powerful advocate in addressing such issues and affirming the identity, dignity, and presence of Black students at Northwestern.

In its early stages, FMO focused primarily on the social needs of Black students at Northwestern. At the same time, another Black student organization emerged with a more outward-facing mission centered on civil rights activism: Afro-American Student Union (AASU),led by James Turner, a graduate student in sociology. AASU members offered legal and financial support to activists involved in civil rights campaigns in the South, especially in response to arrests, beatings, and even killings of demonstrators.

Between fall 1967 and April 1968, a series of confrontations between Black students and campus fraternities signaled rising tensions and served as key precursors to the Bursar’s Office Takeover. One such incident occurred when the Sigma Chi Fraternity and FMO hosted separate parties in close proximity. Although some FMO members were invited to attend the Sigma Chi party, several fraternity members made it clear they were not welcome. A confrontation ensued that escalated into a physical altercation involving both campus security and Evanston police.

The situation worsened when police officers used mace, but only against two Black male guests, who were not Northwestern students. They were arrested, charged with mob action, and given high bail amounts of $5000 each. Meanwhile, no charges were filed against the Sigma Chi members. Outraged by the blatant injustice, Black students gathered the next day in Sargent Hall to strategize how to support the arrested men and hold both the University and the fraternity accountable. That same day, seventy Black students marched to the home of Northwestern President Roscoe ‘Rocky’ Miller to express that they no longer felt safe on campus and asserted that it was “the responsibility of the university to protect the bodies of all its students.” Miller advised them to take their concerns to Dean of Students, Roland “Jack” Hinz.

The following day, during a preliminary court hearing for the two arrested men, more than 80 Black students assembled at Scott Hall Grill. Many of the graduate students present, some of whom had firsthand experience in civil rights organizing and were engaged in academic study of inequity, encouraged the undergraduates to understand the broader institutional structures that allowed such an incident to occur. The group then marched together to the courthouse, where they filled approximately seventy percent of the courtroom. The judge reduced the defendants’ bail. The students later quickly raised the funds needed to secure their release.

Despite these developments, the University initially declined to discipline Sigma Chi for their role in the altercation. In response to continued pressure from Black students, the administration eventually placed both Sigma Chi and FMO on social suspension, pending an investigation. While this outcome frustrated some, it was also seen as a victory. It affirmed the power in collective action and prompted FMO to reevaluate its mission. As a result, FMO formally adopted a political stance, shifting from a primarily social organization to one that explicitly advocated for the well-being of Black students on campus.

Sources

Visit the Bibliography page for sources consulted in this essay. Interviews were also conducted with the following Northwestern University alumni, Clovis Semmes, Herman Cage, Kathryn Ogletree, Leslie Harris, Jean Semmes, and James Pitts.