By Robin Pokorski

Gwendolyn Brooks’ “The Anniad”

“Nine Greek Dramas… White white white. I inherited these White treasures,” Gwendolyn Brooks (1917-2000) wrote in her 1996 autobiographical work, Report from Part Two. She meant this statement literally: when her parents, David and Keziah Wims Brooks, passed away, she moved the mahogany bookshelf her father gave her mother as a wedding present into her bedroom. It was still filled with the green leather-bound volumes of the Harvard Classics that her father read to her as a child. But her inheritance can also be interpreted figuratively, in the way that Brooks borrowed and recast elements of Greek and Roman epic and myth in her poetry. Her attitude towards this inheritance is one of appreciation for the beauty of form and language in classical drama and epic but also of frustration with its whiteness.

Brooks was born in Topeka, Kansas, but grew up and lived her whole life on Chicago’s South Side: first in the Hyde Park neighborhood and then in Bronzeville, which was a center of African-American cultural life in the middle of the 20th century. In high school, Brooks translated substantial chunks of Virgil’s Latin epic, the Aeneid, and even wrote a mock lament “To Publius Vergilius Maro”:

Oh, Vergil, dust and ashes in thy grave

Wherever thy grave sepulchered may be

Forgive me this small speech, wherein I rave

That thou didst ever live to harass me.

Oh, not that I do not appreciate

The mild, concordant beauty of your lines—

But I am puzzled by them; I translate,

And every word seems but a set of signs.

Brooks was both attracted to the beauty of the Aeneid but also frustrated by it.

In 1949, Brooks published her second poetry collection, Annie Allen. In 1950, she was awarded a Pulitzer Prize for the collection, becoming the first Black author to win the award. The poems, much like those in her first volume, A Street in Bronzeville (1945), featured characters who resembled denizens of the neighborhood and scenes that were like those she observed out her windows. Annie Allen is divided into three parts and follows Annie, the protagonist, as she grows up and becomes a mother. The central section, “The Anniad,” plays with the form of the ancient epic, transposing it to working-class Black Chicago. In a 1970 interview, Brooks explained, “It was my little pompous pleasure to raise [Annie] to a height that she probably did not have, and I thought of the Iliad and said, I’ll call this ‘The Anniad.’” By subverting the traits of the heroes of ancient epic, Brooks stakes a claim that the form can apply to Black women’s lives. Achilles, Odysseus, and Aeneas, the heroes of ancient epic, were all wealthy men, and 19th– and 20th-century readers assumed that they were white. Annie, on the other hand, is a poor Black woman.

Annie’s young adulthood, the subject of “The Anniad,” makes a fitting emotional epic. Annie experiences a turbulent first love followed by disappointment. The collection was written shortly after the end of the Second World War, and Annie Allen’s first lover, the Tan Man, is an unfaithful soldier, recently returned from the battlefield. His betrayal causes her to look elsewhere for satisfaction—and she finds it among the pages of classical authors. She:

Twists to Plato, Aeschylus

Seneca and Mimnermus

Pliny, Dionysius…

Who remove from remarkable hosts

Of agonized and friendly ghosts,

Lens and laugh at one who looks

To find kisses pressed in books.

Brooks also used the poem to play with form, creating what she called the “sonnet-ballad.” It mixed the formal structure of the sonnet with the story-telling of a ballad or epic.

Chicago and national newspapers were generally favorable in their reviews of Annie Allen, though reviewers were less convinced of the poetic merit of “The Anniad” than by the rest of the collection. The reviewer for the Chicago Defender, the venerable African-American daily newspaper, concluded that “good poetry is a continuing joy and Miss Brooks’ ‘Annie Allen’ certainly comes under that heading.” But “The Anniad” seemed “more studied than” the rest of the collection in the reviewer’s opinion. The New York Herald Tribune’s reviewer was also lukewarm towards “The Anniad.” It “is marred by rhetoric,” the reviewer said, “sacrificed to a fantasia mixing surrealism, bacchanalian images, religion, a kind of cinematic drama, and even classical references.” For that reviewer, the classical elements of the poem capped off a list of elements that made it inaccessible. But, the collection’s mastery of form convinced the Pulitzer’s judges in 1950.

In 1967, Brooks’ understanding of the purpose and audience of her work underwent a major shift that led her away from incorporating self-consciously classicizing elements in her poetry. She attended a writers’ conference at Fisk University, where she was introduced to younger, more radical Black voices who were more interested in celebrating Blackness than in assimilating into white American culture—and who perceived Greek and Roman classics as part of that white culture. After the conference, she said, “My aim, in the next future, is to write poems that will somehow successfully ‘call’ all black people: black people in taverns, black people in alleys, black people in gutters, schools, offices, factories, prisons, the consulate… not always to ‘teach’—I shall wish often to entertain, to illumine.” In 1972, she published her first autobiographical work, Report from Part One, which barely mentions her Pulitzer or Annie Allen. The implication seems to be that her previous poetry, and perhaps especially Annie Allen, did not successfully “call” a Black audience.

Brooks’ fellow Chicago poet and the cofounder of Black publisher Third World Press Haki Madhubuti (formerly Don L. Lee), agreed. In his preface to Report from Part One, Madhubuti gave a scathing interpretation of Brooks’ use of classical imagery and form. He said: “Annie Allen, important? Yes. Read by blacks? No. Annie Allen, more so than A Street in Bronzeville, seems to have been written for whites.” And part of the reason for that, Madhubuti says, is that “The Anniad” “requires unusual concentrated study” and stirs no emotion or sense of home in him. For Madhubuti, Brooks’ post-1967 work, especially In the Mecca, is her “epic of black humanity.” When she stopped consciously trying to use elements of the white, European canon, then she was able to write the sort of epic that called to her Black audience’s changing consciousness.

Even though she stopped consciously employing classical form and imagery after Annie Allen, Brooks’ classical inheritance continued to appear in her post-1967 work. In the Mecca (1968) opens with a poem of the same name. It is set in the Mecca, an apartment building at State and 34th Streets that had opened in 1891 as the height of luxury but, by the mid-20th century had fallen into disrepair before being torn down in 1952. The poem follows Mrs. Sallie as she arrives home after work and realizes that her daughter, Pepita, is missing. “SUDDENLY, COUNTING NOSES, MRS. SALLIE / SEES NO PEPITA. ‘WHERE PEPITA BE?’” So begins a frantic search for the missing little girl, which introduces readers to the Mecca’s denizens. None of them have seen Pepita, until she is found murdered. Rather than concluding with Mrs. Sallie’s despair, Brooks strikes a hopeful note with the final lines:

“I touch”—she said once—“petals of a rose.

A silky feeling through me goes!”

Her mother will try for roses.

She whose little stomach fought the world had

wriggled like a robin!

Odd were the little wrigglings

and the chopped chirpings oddly rising.

The little wrigglings, rising chirpings, and the rose signal a potential for a spring-like rebirth; so does Pepita’s name, which means “seed.” Literature scholar Tracey L. Walters argues that “In the Mecca” can be read as a recasting of the Demeter and Persephone myth, in which Demeter pursues her daughter to the depths of Hades and Persephone’s return to the land of the living occasions the return of spring. Whether or not Brooks was intentionally reshaping this myth, Walters’ interpretation suggests that classical themes continued to resonate with Brooks even after her transformation of consciousness in 1967.

Brooks’ Pulitzer Prize for Annie Allen came at the start of a long career, encompassing a stint as the Illinois Poet Laureate and as the poetry consultant to the Library of Congress, as well as a Guggenheim Fellowship and the Medal of Distinguished Contribution to American Letters. She supported young Black poets and emerging Black publishing houses, including Madhubuti’s Third World Press. In the 1970 interview, Brooks said that “every stanza” in “The Anniad” “was worked on and revised, tenderly cared for. More so than anything else I’ve written, and it is not a wild success; some of it just doesn’t come off. But it was enjoyable.”

Sources & Further Reading:

Annie Allen is no longer in print but most of its poems, including “The Anniad,” are available in the affordable collection published by The Library of America’s American Poets Project. “In the Mecca” is unfortunately excluded from the collection. Gwendolyn Brooks, The Essential Gwendolyn Brooks, edited by Elizabeth Alexander (New York: The Library of America, 2005).

Gwendolyn Brooks, Annie Allen: Poems (New York: Harper, 1949).

Gwendolyn Brooks, In the Mecca (New York: Harper & Row, 1968).

Gwendolyn Brooks, Report from Part One (Detroit: Broadside Press, 1972).

Gwendolyn Brooks, Report from Part Two (Chicago: Third World Press, 1996).

Gwendolyn Brooks and George Stavros, “An Interview with Gwendolyn Brooks,” Contemporary Literature 11, no. 1 (1970): 1-20.

George E. Kent, A Life of Gwendolyn Brooks (Lexington, KY: University of Kentucky Press, 1990).

Joan Kufrin, “Our Miss Brooks: An Intimate Portrait of Gwendolyn Brooks, Chicago’s Pulitzer Prize-Winning Poet,” Chicago Tribune, Mar. 28, 1982.

Don L. Lee, “The Achievement of Gwendolyn Brooks,” The Black Scholar 3, no. 10 (1972): 32-41.

Carl Phillips, Coin of the Realm: Essays on the Life and Art of Poetry (Saint Paul, MN: Graywolf Press, 2004).

Michele Valerie Ronnick, “Virgil in the Black American Experience,” in A Companion to Vergil’s Aeneid and its Tradition, ed. Joseph Farrell and Michael C. J. Putnam (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2010), 376-390.

Tracey L. Walters, African American Literature and the Classicist Tradition: Black Women Writers from Wheatley to Morrison (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007).

David Withun, “African Americans and the Classics: An Introduction,” Black Perspectives (blog), African American Intellectual History Society

Read more about Brooks at the Poetry Foundation website.

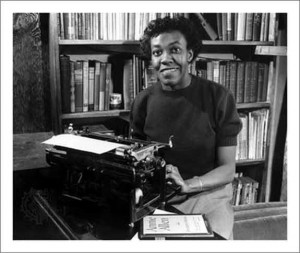

Below, Brooks at her typewriter with a copy of Annie Allen.