As We discussed McClintock’s Imperial Leather: Race, Gender, and Sexuality in the Colonial Contest in class lectures, searching for the book I came about a heavily illustrated section of the book. Unable to access the images, but eager and intrigued, I came about an article which talked about these illustrations she visited and talked about. One of them, which I will be discussing in this blog, and referring to the continuity spectrum of such advertisements.

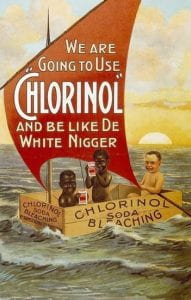

The book cites an advertisement where three little African boys sail on a supposedly seen boat which is made out of a soap box. One of these boys has his skin bleached white, while the text underneath it reads “We are going to use ‘Chlorinal’ and be like de white nigger.” This advertisement spoke the harsh truth of blatant internalization of white as pure, clean, and worthy of living as compared to the people of color, who have to try and achieve this level of whiteness to be considered worth living and of importance.

Further analysis of the picture, we see the bleached white child sitting separate from the two black children, which depicts the reality, even in advertisements and amongst children, of the wall created from color, strengthened by racial fetishism. Not only that, the white child is the one having control of the boat, and thus has control of the oar, projecting that the world is dominated by the white, and they only have control of them – driving the ‘others’ and using them to make their path a success.

While we may consider this to be only present in books of history and with the wide-spread activism prevalent now, it should be a disgrace to even have hints of such advertisements on our mass media. However, in reference to being a colonized country myself and being a South-Asian, our brown and dusky skin has always been a source of inferiority for ourselves, leave alone to the wider European community. We have internalized the notion that white is indeed pure, that being fair is the epitome of beauty, that to be perfect, the first thing needed is being white. This internalization wasn’t just born into us, it was build and inscribed throughout history – from advertisements such as those in McClintock’s book. It is prevalent even today. Recently, a very popular local whitening cream named ‘Fair & Lovely’ which has a tremendous consumer market, was targeted on social media for distorting women’s self-esteem and framing as white being the ultimate form of beauty. The name itself, denoted what two elements made the ultimate combination of superiority for females.

It was until recently a month ago, that this years long beauty industry decided to change its course in Pakistan and value the true colors of females where the Fair and Lovely team issued a public apology, but still continued selling its products under the name ‘Glow and Lovely’. It is worth noting that although the name change is a first step, it is still continually extending the notion of having white skin, of using it as mode of glorifying racism, leading to the very much prominent, commodity racism. According to McClintock, ‘Commodity racism is a term that refers to the way in which race and commodities mutually inform one another’. This commodity racism was the British’s key tool in the colonization and has been successful then, and is there even now, encompassing the powerful image of domination of the white today. It then comes to the question, if we will ever realize the long-term consequences of this infatuation with whiteness, because if we don’t stop now, these bleaching creams will be the ones dominating us, even centuries from now exasperating the racism we have been trying to curb.