Close to Home: Place-Based Mobilization in Racialized Contexts (With Sally Nuamah)

How do citizens respond to geographically targeted policy changes? Most research on the effects of public policies focus on indiviuals directly affected by national issues (e.g. senior citizens, welfare recipients, veterans). This analysis investigates the political effects of targeted local policies on the communities in which these policies occur. Focusing on the case of Chicago, where the school district closed over 50 schools in 2013 (the most in a single year by any city in U.S. history), we use election results, the Cooperative Congressional Election Study, and original data on public school closures to evaluate how large scale, geographically targeted public school closures shape the broader political attitudes and behavior of the communities affected. Our analysis reveals that proximity to a school closure is positively associated with decreased support for school policy, decreased electoral support for the elected official responsible for the policy, and increased political participation. These findings bridge literature on policy feedback, public opinion, and urban politics to support a model of place-based policy learning and opinion formation consistent with collective interest.

You can read a draft of the paper, which has been conditionally accepted for publication at the American Political Science Review, here. An MPSA presentation based on the paper is here and a Washington Post editorial version is here.

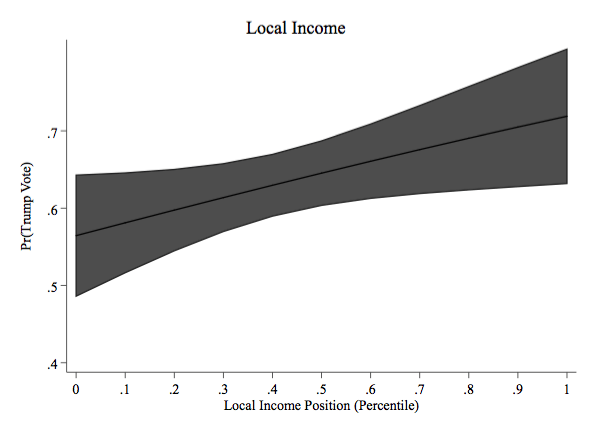

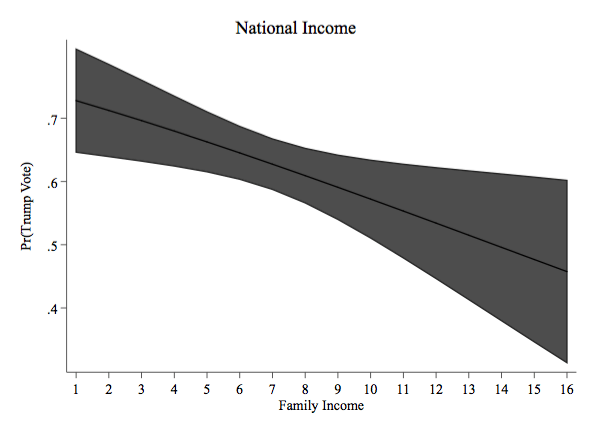

Locally Rich, Nationally Poor: Income, Place, and White Voters in the 2016 Presidential Election. (With Spencer Piston and Luisa Godinez Puig)

Social scientists routinely examine relationships between income and political preferences as a window into class divisions in American politics. But existing measures implicitly compare people to others in the national economic distribution, even though a given absolute income level (e.g., $54,000 per year, the 2016 national median) might mean something very different in Clay County, Georgia, where the median income is about $22,000, than in Greenwich, Connecticut, where the median income is $203,000.

We build on existing scholarship by incorporating, in addition to the standard measure of income, a measure of one’s place in their local income distribution. We apply this approach to the question of whites’ voting decisions in presidential elections since 2000, focusing in particular on 2016. The results show that Trump’s support was concentrated among nationally poor but locally affluent whites. The pattern holds for Republican candidate support in most recent presidential elections. These results suggest that social scientists interested in class and politics would do well to conceive of income not just in absolute terms but also in relative terms: relative to one’s neighbors. Link to article here and ungated here. Link to Washington Post Monkey Cage blog post here.

The City Re-centered?

Research on U.S. federalism has long suggested that the nation’s fragmented policy geography hamstrings local actors that might work to reduce inequality because of competition between places for businesses. Recently, proponents of a “New Localism” have suggested that national gridlock and recent urban “renaissance” may make cities a relatively promising site for addressing inequality and collaborative problem solving on major issues. Using data from the census and city policy enactments, this chapter assesses the premises of that argument by analyzing changes in property value concentration across major U.S. metropolitan areas. I find that while the urban renaissance is indeed real–especially in cities with booming knowledge economy sectors–there is only limited evidence that such a boom has generated significant local policy effort to spread the wealth generated by re-concentration. Forthcoming in Thelen et al American Political Economy. Link to draft.

In the Streets and on the Hill: Conceptions of Pluralism Between Cities and Congress over National Civil Rights Legislation (in Dilworth and Weaver, eds 2020)

This chapter contrasts the positioning of big-city leaders on civil rights and racial justice issues at the local and national levels during the Long New Deal. The national anti-racist pro-civil rights coalition included some of the same persons who upheld and exacerbated racial hierarchies in local politics. This seeming contradiction suggests that it is more useful to think of the fight for minority rights in a democracy as a coalitional politics of uneasy alliances, rather than a Manichean ideological struggle between members of transformative egalitarian and white supremacist racial orders. Link to preliminary printed version here.

Chicagoland Metropolitan Area Neighborhood Study (With Traci Burch, Matthew Nelsen, Kumar Ramanathan, and Reuel Rogers)

This survey project investigates the opinions and behaviors of Chicagoland residents. We are seeking to learn more about how people feel about their neighborhoods, what their policy priorities are, and how that connects to politics. We’re cleaning and running analyses on the data for the project right now. Here’s one brief example.

The pilot study for the project was generously supported by a Weinberg College “W” Seed Grant and the Center for the Study of Democratic Politics.

Pride or Prejudice? Racial Prejudice, Southern Heritage, and White Support for the Confederate Battle Flag (With Spencer Piston and Logan Strother)

Rep. John Rankin (D-MS/CSA), who wore a Confederate flag necktie when he argued against racial integration.

Debates about the meaning of Southern symbols such as the Confederate battle emblem are sweeping the nation. These debates typically revolve around the question of whether such symbols represent “heritage or hatred:” racially innocuous Southern pride or White prejudice against Blacks. In order to assess these competing claims, we first examine the historical reintroduction of the Confederate flag in the Deep South in the 1950s and 1960s; next, we analyze three survey datasets, including one nationally representative dataset and two probability samples of White Georgians and White South Carolinians, in order to build and assess a stronger theoretical account of the racial motivations underlying such symbols than currently exists. While our findings yield strong support for the hypothesis that prejudice against Blacks bolsters White support for Southern symbols, support for the Southern heritage hypothesis is decidedly mixed. Despite widespread denials that Southern symbols reflect racism, racial prejudice is strongly associated with support for such symbols.

Link to article here and ungated here. Related LSE Blog post here. Related Washington Post Monkey Cage post here.

When the Second Dimension Comes First: Culture-First Forces and the Politics of Social Provision (with Quinn Mulroy)

Xenophobic political forces have recently been unusually successful in several western democracies. These groups are often characterized as populist in contemporary scholarship. In this paper, we approach from a different angle by focusing on the political priorities of these groups rather than their political style. We introduce the alternative concept of culture-first forces: political groups that prioritize their “second-dimension” (cultural) preferences over the “first dimension” (economic) concerns around which 20th century party systems were typically organized. What types of policy and governance positions are we to expect from such forces? The answer, we suggest, is complex, and contingent on the timing and sequencing of key factors in the diminished state model. We illustrate this model with a comparative historical analysis of two cases of culture-first forces in leading western democracies: white southern Democrats in the U.S. and the Front National in France. These groups dramatically shifted their first-dimension positions while defending their second-dimension priorities, and in the process, both shaped and were shaped by the distinct political systems in which they operate. While culture-first forces eventually championed in a diminished state model in the U.S., the Front National shifted in the opposite direction and eventually embraced a generous (though nationalist and exclusive) welfare state in France. Relying on parallel contemporary sources from the two cases, this paper identifies the sequence of welfare statebuilding, diversity, and culture-first force emergence as important to explaining the different trajectories of culture-first forces operating in different political systems. See latest version here.

Going Viral and Making Waves: Social Media Use Among Aldermen in Chicago, 2015-2018. (With Kumar Ramanathan)

This paper, part of a larger project on place-based Facebook groups in Chicago, tests theories of “professional” and “amateur” politicians’ communication patterns on social media. We find that ideologically outspoken posts about non-local issues garner more community engagement, especially after the 2016 national election, but that such dramatic position-taking on high-profile issues carries risks as well as rewards, generating both polarized debate and potentially short-circuiting career advancement. You can read the paper here. An MPSA presentation based on the paper is here.

Filibuster Vigilantly: The Liminal State and 19th Century U.S. Expansion