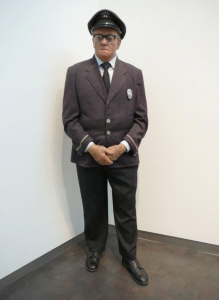

The contemporary wing of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art greets the visitor with a medley of ubiquitous sights. Unlike the rest of the marble-pillared and gold-leafed building, the room immediately envelopes you into tall bright white walls dashed with stanchions and confronts you with an array of crisp plinths and cubes settled around oversized canvases. Still as the objects, other visitors pose thoughtfully between paces and a museum guard gazes onward, nestled deeply in the corner. In Bloch gallery, one particular guard has a scrutinizing and somewhat sour expression painted across his face. Most of the visitors bypass his corner without a second thought. Others quiet their voices and lower their cameras. A few visitors, however, notice the rectangle next to him covered with a name, date, medium, and a tidy, staff-reviewed description. As they draw near, his stoicism becomes unsettling. The attempts to attract his attention range from slowly walking parallel to him, to aggressively waving their hands in front of his face. The museum guard is Duane Hansen’s Museum Guard, 1975, polyester, Fiberglass, oil, and vinyl, 5 feet 9 inches x 21 inches x 13 inches.

Unenthused, the figure of an aging museum guard stands in the gallery’s corner carefully positioned for optimal surveillance. His chin is slightly uplifted conveying a certain attentiveness his hooded eyes and straight mouth conceal. His face is a mixture of sunken cheeks and deep lines framed by thick-rimmed glasses and an old-fashioned guard’s hat labeled GUARD 33.

Under the plastic rim of the hat, spreads of greying hair unfurl messily over his ears. His portly figure is shifted slightly to the right presumably after a tiring shift at his post. He is cloaked in a full uniform of synthetic authority and garnished with a gaudy badge. His hands are clasped loosely yet sternly in front of him ready to gesture toward any visitor who dare touch the art.

As lonely as the realistic sculpture may be in a sea of canvases, the museum guard is just one of the many excruciatingly ordinary folks created by Hanson. Conjured through a live-casting process, his sculptures capture the essence of the tertiary characters in our life. He translates how we as humans use and alter our bodies —unconsciously or consciously—creating formal elements of art in a reimagined way. The line-work qualities of a Hanson piece are loose hairs, clothing wrinkles, veiny formations, or crow’s feet. The color either saturated in costume or accessories, or muted through a washed out tiredness that comes with age. The texture of cellulite, sunken cheeks, or fat rolls are emphasized through an honesty only fluorescent lighting in bad dressing-rooms can create. Characters like Car Dealer, Flea Market Lady, Traveler, Man on a Bench, Bus Stop Lady and Young Shopper are all familiar faces. The extras in movies, the bystanders to our days, the receivers of glances and the strangers met through a moment of accidental eye contact.

Through their frumpy clothes, poor posture, or unexcited expressions, the subjects aren’t necessarily demanding attention. Most really aren’t that pleasant to examine. But through Hanson’s touch, the commonplace is mystified.

The otherwise inconspicuous facial expression or subtle body language of the subjects becomes a psychological study in their motionlessness. The lines blur between the model’s natural existence and Hanson’s artistic intentions. Hanson’s pieces not only question what an artist creates, but also questions what art is, what it should be, and how can perceived non-art art be criticized. Are you critiquing a natural form, or are you critiquing the interpretation through medium? In their final form, the obliviousness of the figures is both performative and undisturbed. Although seemingly more self-aware through the attention solicited in a gallery, the sculptures still hold on to the earnestness of their imagined contexts.

Characters like the Tourists II are tremendous in their noticeability, but don’t take up more space then they might need. The Baton Twirler is dressed for a performance but points her line of vision upward as if recalling choreography. The characters either notice the viewer, ignore them, or remain indifferent, but regardless of the relationship the exchange is always the most natural option possible.

But out of all of Hanson’s characters, Museum Guard is the most striking. His sense of the space he inhabits amplifies the fascinatingly ordinariness of his presence through merely belonging. Patrolling from the corner, the sculpture holds complete plausibility. His severely outdated uniform looks like an old man’s quirk, a stubborn decision rather than his time-encapsulation.

Through Duane Hanson’s sculpture, important questions concerning the role of the museum guard within larger cultural institutions surface. Why did so many visitors ignore or remove his presence from the space? What conditions lead to only a minimal percentage of visitors noticing him or merely approaching close enough to realize he is not a live person?

The guard’s psychological effect ranges from visitor to visitor. Much like the alive guards at the Nelson-Atkins, the Museum Guard’s presence is dismissed. Erased from the visitor’s hard earned culture-enriched leisure time, the guard works on the clock, on his feet, lonely until someone confides they need to know where the nearest bathroom is located.

His ordinariness is polite, not wanting to interfere with the visitor’s experience. And some visitors don’t want to be disturbed. However, some visitors project invisibility onto the Museum Guard (and museum guards) as to not disturb them. This performative erasure in the context of an art gallery only adds to Hanson’s delightful irony since every object in the room is ideally processed and noticed in great detail.

In a museum best known for its oversized, tourist photo-magnet artworks, the Museum Guard holds a special place in the Nelson-Atkin’s permanent collection. More than anything, it’s a huge “Gotcha!” Moment. Its whimsical and cheeky but also a vessel for introspection. The liminality of the guard between observer and the observed is constantly being challenged, discovered, and usually by the end of the exchange documented through a photo. He is viewed while still having the power to view. The guard repositions the visitor as the spectacle while objectifying the ordinary.

The piece holds an uncanny familiarity and a relatableness, yet produces a distance. Maybe we haven’t seen this guard before, but we’ve seen his essence. Duane Hanson uses the extract of humanity to represent the everyday people who otherwise don’t garner much attention. Don’t get me wrong though. He’s not reducing this essence into a Michelin star gastrique of marble Adonises, rather, reflecting it as purely and as candidly as he can. He and his cast of characters bring the latent wonderfulness surrounding us in the hectic real world into the empty, white focus of a contemporary museum. The models the sculptures, the sculptures the models. The artwork as extraordinary as the museumgoers themselves.

2,777 Comments

Keep this going please, great job!