I arrived in Venice alone on November 12, 2015. I had been abroad for about two months, and this was the moment I had been waiting for. My scrappy, industrious European adventure would make me feel without a doubt that I hadn’t squandered my time here. I was unfamiliar with traveling alone and terrified that I would drop a ball that ruined the whole trip, but so far I had figured out how to print my Ryanair boarding pass so I wouldn’t be charged 60 pounds at the airport and how get to London’s distant budget airport by 4 AM without major issue. I was even lucky enough to be routed into the normal airport (rather than the budget airport) in Venice due to fog! I was starting to feel like I was going to make it as I boarded the water bus. Student ticket in hand, I was going to one of the most famous art events in the world: the Venice Biennale.

The next day I walked along the water to the Giardini, one of the two largest Biennale venues. I crossed bridge after bridge, and my feet were just starting to fatigue from a long day’s travel when I saw the green gardens appear ahead out of the fog. I spent all day at the Giardini, taking in the main curated exhibition, “All the World’s Futures,” and several national pavilions. In the furthest corner, I found the Polish Pavilion and watched Halka/Haiti 18°48´05˝N 72°23´01˝W by C. T. Jasper and Joanna Malinowska (image below). This piece is a simply-edited panoramic video of the Polish opera Halka performed in a Haitian village, but I watched, mesmerized, for 25 minutes because I knew I would probably never see it again.

I stumbled back to my hotel in a daze, ready to settle into bed until the next day. Then my phone connected to the wifi and I started getting the notifications. News of the violent attacks in Paris permeated the safety of my locked hotel room door. I learned that my Northwestern roommate from freshman year had attended the soccer match that came under attack, but she had returned home safely. Still, attack after attack terrified the city as I sat in Venice, shocked and alone and sad.

The next day, it was just slightly harder than usual to open my door and face the world outside. But today was my only day to see the second part of the Biennale. I followed nearly the same path along the water in the fog to the Arsenale. It didn’t take me long to realize I wasn’t going to enjoy the show that day. I wasn’t feeling at all optimistic about “All the World’s Futures,” and I was greeted in the first gallery by two neon works by Bruce Nauman called Eat Death (1972) and Raw War (1970). I was not in the mood.

I powered through the main show and glanced through a couple of pavilions before collapsing into a chair at the café. It was time to go.

****

I didn’t think it about the Biennale that much in the following couple of months. When I returned to the U.S., I would list it as one of the things I did that meant I hadn’t squandered my time abroad. I felt very lucky to have been able to go, but I couldn’t deny my experience was colored by the terrible events in Paris. It came crashing back into mind, though, when I was introduced to the Google Cultural Institute by one of my courses early in 2016.

The Google Cultural Institute struck me as a thing of beauty. I was no stranger to searchable databases of artwork, but the interface was so polished and smooth. There were countless virtual exhibitions on subject ranging from the fall of the Berlin Wall to Rembrandt van Rijn, and it was all so interesting and easy to interact with. I was blown away by the fact that I could access images of so many works from so many different institutions in one place for free. I could happily get lost down the rabbit hole of virtual tours and collections, reveling in this new accessibility of the arts.

I found the Venice Biennale 2015 project on their news page. I was surprised and intrigued, so I clicked through the “All the World’s Futures” Giardini digital exhibition. It was very strange having been there before, and it brought up mixed feelings about the time I had spent in Venice not long ago. For the first time, I could see odd things about the Google Cultural Institute that I had not questioned before. The context of my viewing the weekend of the Paris attacks had changed my experience of the artwork, but temporal context was eliminated from the Google exhibitions. This emphasized the vague contemporaneity of the Biennale.

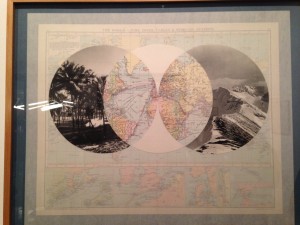

I was unable to decide whether I was grateful I could review the Arsenale show after the fact, or whether the stunted experience just made me feel worse for not taking full advantage of being there. On the one hand, I was able to identify a work I liked; I had taken a picture of it but forgotten to note the label information.

My iPhone image, November 13, 2015.

Google Cultural Institute, Giardini Digital Exhibition, Installation Photo

Further, I was able to view an in-depth, documentary virtual exhibition of Halka/Haiti in the Poland Pavilion, but there was no video clip of the work, so I had been right in thinking I would never see it again. The whole experience of reviewing the Biennale via Google was strangely unsettling, and it me to research more about this platform.

The enigmatic, contradictory Google Art Project launched February 1, 2011 to little fanfare and mixed reviews. There were 17 original partner institutions that made all or part of their holdings available online. While most critics lamented the bugs and whirling experience of indoor streetview (largely unchanged in 2016), some disparaged the concept itself because the photography, however hi-def, could never equal the experience of the real thing. Although I basically agree, this strikes me as incredibly elitist. Not everyone is going to have the means to make it to the Uffizi in person, so giving a virtual option radically expands the group of people able to indulge their interest in arts and culture. Many museums are also excited about the possibility of mitigating crowds.

Aside: there are some gray areas to this accessibility.

While they clearly want users to be able to create collections (which sort of remind me of Pinterest), they dangle their “Open Gallery” exhibition technology before budding digital curators (read: me) before dropping the bomb that it is “invite only.”. Okay. So, the wider audience is meant to be “culturally curious” but they should not be granted the same tools as culturally authoritative institutions. Heavens, no…

It didn’t take too long after the launch before people said, “Wait… How are you profiting from this Google?!?!?!” The short answer is, they aren’t. This subset of the company is strictly non-profit. However, when pressed, the Institute’s director Steve Crossan said, “There’s certainly an investment logic to this. Having good content on the Web, in open standards, is good for the Web, is good for the users. If you invest in what’s good for the Web and the users, that will bear fruit.” Okay, but also, Google is good at gathering and selling our metadata and great at keeping quiet about it. It’s a new and mind-bending possibility: billions of art and cultural objects aggregated, and billions of people interacting with them, showing Google (and maybe cultural institutions for the right price) what people are actually interested in (and possibly willing to pay for). Although this service is “free of charge,” there is an untold amount of money bound up in it nonetheless. It suddenly felt ironic that a major theme of the Biennale was “capital” and how it has changed in the 21st century. Evidently it’s a crazy new world.

A persistent problem for Google, however, has been copyright. There are next to no Picasso artworks in the database, and some artworks must be blurred out in the virtual tours. This has had ivory tower types questioning the usefulness of the Google Art Project to *serious scholarship*. They say that zooming in a lot is nice and all, but they can’t reproduce works for free so what’s the difference?

And at the end of the day, I’m kind of exasperated at everyone, including myself, ruining the fun. Of course there are so many complications, capitalistic and otherwise, making the dream of free access to every art object in reproduction impossible. Fine. Just take it as it is. Looking at pixels will never beat looking at paint. This we all know. But what about the ephemeral? For my thesis, I have spent the better part of a year thinking about an exhibition that occurred in 1962, trying to reconstruct its design and its meanings. I have been able to find no curator notes, no drafts, and very few installation photographs. All I can say is, a scholar attempting to study the 2015 Venice Biennale in the year 2080 is probably going to have a much easier time making heads or tails of it, thanks to Google.

Featured image: High definition detail of Sunday on La Grande Jatte, Google Cultural Institute.

1,967 Comments

response at all from jual dress batik your potential network connection.

Remember in last week’s Sewa Alphard Bekasi blog when Sarah mentioned to the professional

your new connection Rental Mobil ke Bandara informs you about an internship, you apply, matriculate in the program