Tseng in His Mao Suit

The Mao Suit is almost always the first thing you notice in the hundreds of pictures that Tseng Kwong Chi took.

It stands out from the crowd who were in extravagant Chinoiserie outfits,

from the western landmarks that were familiar even to tourists through books and postcards,

and from the western landscapes that had inspired the twentieth century landscape artists.

We see Tseng in the suit around the world from New York to Paris to London, and for occasions from television shows to parties to art receptions, the suit almost as a signature: He is the one who stands straight when others are all twisted, the one who is in a single color when others are in various patterns.

The Two Times Tseng was not in the Mao Suit

Twice in the exhibition, however, Tseng was not in the Mao Suit

1. 1981, Washington D.C., the “Moral Majority” series with Daniel Fore.

Tseng and Fore are standing shoulder to shoulder in front of a crumpled American flag. Many stars only show part of themselves, and the three visible stripes twist like seaweeds. Fore is a big man: Tseng is only at his forehead, and his tweed checkered suit could probably fit two Tsengs. While Fore dresses formally, wearing one pin on each of his collar, a tie clip, and shiny oiled hair, he does not seem too ready for the photo: his suit is slightly wrinkled at the pocket and below his left shoulder, and he opens his mouth but the double chin comes before the smile manages to. Tseng is, on the contrary, relaxed and smiling, slightly leaning backwards with his hands behind his back and two ends of his tie apart.

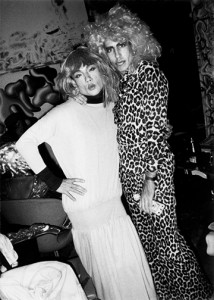

2. 1988, New York, in Kenny Scharf’s studio, Kwong Chi and Kenny.

In front of abstract paintings, Scharf has his right arm around Tseng’s neck, leaning his body against Tseng’s, and Tseng has his left hand on Scharf’s back. Tseng is in a long white dress with low waist line over a black high neck sweater. Wearing a shiny wig that goes right below his shoulder, straight and with bangs, and wearing heavy eye make ups, Tseng pouts his lips. Scharf is in a long leopard print dress with black pearls knotted in front of his chest. Wearing blonde ringlets running on his shoulder, Scharf shows little emotion but looks straight into the camera.

Impression Through Appearances

Twice in the exhibition, we see Tseng separated from his signature, as if he is becoming someone else. In fact, he has become someone else at least to us who know him only as the audience of his exhibition: From the expressionless figure, an explicit and intentional outlier whose mysteriousness deepens as the sunglasses block his eyes, he becomes the man who, at least in the first glance, stands naturally beside a conservative like Fore, and fits naturally in a drag party with new outfits.

This is when we realize how our perception of Tseng changes when he simply changes his outfit, and thus, how heavily we rest our impression of a person on his appearance.

“Westernness” is an appearance.

You take off your Mao Suit or kimono, and put yourself into a seersucker suit or a mini dress. You change your hard-to-pronounce Chinese name into a catchy western name, say Kwong Chi to Joseph. You carefully erase the accent that your parents have (In fact, Muna Tseng, Tseng’s sister says at Northwestern on Oct. 27, 2016: “Any trace of accent is a source of vulnerability.”), never pronouncing “think” like “sink,” and eat the last syllable of each sentence to sound relaxed. You tan yourself, and pick up the smile that shows eight of your teeth.

Femininity is an appearance.

You grow your hair, or put on a wig. You wear long dresses, pearls, and earrings. You make your stiff body lithe, hold back your arms, and walk with your two feet in the same straight line. You drop your wrist sometimes as you talk in high pitches.

The party-animal-personality is an appearance.

You pull yourself up from the bed on tired Friday nights, dress up, put on make ups and put up the contagious enthusiasm. You love everyone, compliment their clothes and their dates, drink with them, laugh with them and take pictures of you drinking with them laughing with them.

Difference Without Inequality: Dealing with Appearances

However, to know people by their appearance is not wrong, and in fact is inevitable given our nature of finite beings. We can only observe what people look like, what they say, and what they do to us, but can never know what they are like when we are not observing, not to mention what they think, what they believe—and ultimately, who they are. Since all we have about Tseng are his photos and a video clip, his appearance in them is all that we have to base our knowledge of him on.

Neither is labeling, that is, grouping people into categories according to such appearance inherently wrong. When given the many aspects of people, we naturally have to form words to pin down the meanings, to make one idea separate from another. For example, we see certain traits that belong to the east: Chinese names have two or three words, each word has only one vowel in it, and consonants take on combinations unfamiliar to the western languages. And we call names sounding like that “eastern” to remark these traits we find, merely to differentiate.

The vice lies in the actions that follow, which employ unevenly distributed power to turn difference into inequality. While Tseng, empowered by his Mao Suit which implicates a mysterious power, gained access to “Party of the Year” in Metropolitan Museum of Art, we can see that the other participants are predominately white, demonstrating an institutional exclusion of racial minorities.

The inequality is, unfortunately, not only present in access to such fancy occasions, but usually present in basics rights, and not a unique evil of any time, but has a long history: as Moral Majority would use its power and influence to lobby against Equal Rights Amendment and homosexual rights in the 1980s, as the military would cooperate with the police department and the liquor control agency to arrest homosexuals and push them out of work in the 1950s, and as the Virginia planters would equal African Americans to slaves in the 1680s.

But inequality is not a necessary outcome of difference. The photo above grants me the relief and hope: In the picture, everyone is different, but the difference is not turned into inequality by hatred, but embraced as diversity by friendship.

844 Comments

HappyToon 해피툰 : which has the largest number of webtoons currently being serialized. 해피툰

HappyToon 웹툰추천 : which has the largest number of webtoons currently being serialized. 웹툰추천

HappyToon 해피툰 : which has the largest number of webtoons currently being serialized. 해피툰

HappyToon 웹툰사이트 : which has the largest number of webtoons currently being serialized. 웹툰사이트

HappyToon 무료웹툰사이트 : which has the largest number of webtoons currently being serialized. 무료웹툰사이트

HappyToon 무료웹툰 : which has the largest number of webtoons currently being serialized. 무료웹툰

Hey there! Ready to dive into the excitement of IPL betting? Log in to mr. play and get started now!!

Check out the hottest news and stay informed about match results and player performances with cricket news today Dont miss out on any of the action

HI! I WISH YOU COULD WRITE MORE BLOG LIKE THIS. THIS IS SO VERY GREAT!

https://www.gwolf.info

I READ THIS POST YOUR POST SO NICE AND VERY INFORMATIVE POST THANKS FOR SHARING THIS POST.

https://edwardsrailcar.com

I’ve spent considerable time on this website 918kissauto

Canon printers are available. สล็อตออนไลน์

Each & every recommendation of your website is awesome. JILI WALLET

I also shared the future of marketing/business with JOKER AUTO WALLET

I can’t wait to share this with my friends colleagues. JOKER WALLET

Hit the drums and sing along!!! Live22 auto

with more than 3 decades of experience. MEGA888 AUTO

between our private and public spaces. PG SLOT AUTO

I appreciate you giving me this crucial information. PG SLOT AUTO WALLET

In the end, pussyslot

if you are genuinely interested in watching animes, เว็บสล็อต 168 ฝาก ถอน true wallet

This not only makes you look comfortable, เว็บสล็อตวอเลท

its beautiful stylish. slotxo wallet

service. สล็อต ฝาก-ถอน true wallet ไม่มี บัญชีธนาคาร

What do you know about online shopping? สล็อตเว็บตรง

timely updates on global events. PUSSY888 เว็บตรง

perangkat ini memenuhi ekspektasi pengguna yang paling menuntut. 918KISS AUTO

untuk anda dan dengan begitu anda harus memiliki 1 akun สล็อตjili วอเลท

personalized communication experience. ສລ໊ອດອອນລາຍ

Fouad Mod Betflix wallet

I’ve spent considerable time on this website สล็อตฝากถอนวอเล็ท

Let’s dance through the realm of Amazon trends, JOKER SLOT

Breaking news from around the world! เว็บสล็อต xo ออ โต้

fencing แลนด์ สล็อตออโต้

This became one of the top trending outfits because สล็อตออนไลน์

entrepreneurs, เว็บสล็อตออโต้

Such an accommodating article. เว็บหวยออนไลน์ จ่ายจริง

telling the stories of their wearers solidifying their JILI WALLET

cohesive layout immediately caught my attention สล็อตวอลเลท

handpicked happy birthday quotes wishes from MEGA888 ฝาก-ถอน ไม่มีขั้นต่ำ