The show begins when I enter the room. Tseng Kwong Chi, ready to amaze, pulls the curtain back in a swift motion of pop-star grace. He draws to perform or maybe to fight, welcome or send away. I stand back in awe, excited and afraid. East Meets West beckons.

As I begin to walk through the exhibit, I am initially swept up by the photographs’ glamour. When photographing his tight circle of friends, this glamour is tinted with a provocative transparency. When photographing various pockets of capitalism’s elites, the glamour is satirical, witty and sharp. But as they are two sides of one coin, the aesthetic is the same—big, bold, excessive. As I turn a corner and pass his Costumes at the Met series, bright, glossy teeth sneer down at me from folds and folds of opulent, “east”-inspired fashions. I cringe at Chi’s Mao suit—how it’s geometric cut just almost blends into the event’s extravagant formality, yet stands out, unsettling me in its contrasting, dull grey. I continue. By the time I walk down a row of self-portraits featuring Chi in front of symbolic sites of capitalism, I admit, my brain sags. Though each series covers an independent angle to satirizing specific aspects of capitalism—exoticized fashion at the Met, blindingly narcissistic Republicans, tensions between communist and capitalist, temporal spaces—the photographs’ biting opulence and brazen, satirical messages simply start to blur.

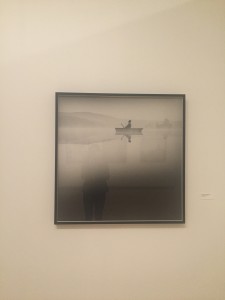

As I stand, numbly staring at Chi in front of the Hollywood sign, something catches my attention. A small, dark figure rests alone and almost unnoticed, hovering in the reflection of the photograph’s framed glass. I turn around. There on the opposite wall, Chi sits on a small boat, his noble and reed-like figure bracing the misty, Vermont dream. I walk over, and am immediately pulled into the photograph’s hypnotic reverie.

Chi’s 1985 photograph, “Lake Ninevah, Vermont,” is from of one of his last projects, The Expeditionary Series. Working with his partner, Kristoffer Haynes, Chi delves deeper into the pictorial field, exploring the technological and artistic potentials of his, at the time, newly acquired, professional-quality Hasselblad camera. The series presents a stark contrast to his other work. Removing himself from the other series’ binary, but consistent glamour, Chi examines more ominous undertones of testy vulnerability. Of the series’ five, featured photographs, “Lake Ninevah, Vermont” is particularly unique. Unlike the other four photographs in which Chi’s placement is disruptive, startling and seemingly accidental, “Lake Ninevah, Vermont” harmonizes a Chi’s presence with his surrounding environment. It offers not a message, but a momentary window, a brief intimacy with the artist.

“Lake Ninevah, Vermont” holds an uncharacteristic softness. Like gazing through a crystal ball, the scene seems shrouded in a thin mist. Upon stepping closer, I notice that there is not a single hard line. The shoreline is defined by a thin release of white, the boat’s definition slightly blurs to its reflection—even Chi is hazy against the faintly shadowed hills. To further smooth the transitions, the photo’s contrast between the photo’s weighted bottom and upper stratosphere is even and perfectly gradual. “Lake Ninevah, Vermont,” mingles in the borderlands between the real and surreal. The hills are painted, using a a traditional, Chinese watercolor technique. In blurring the boundaries between photography and watercolor, Chi creates a hybrid world, sufficient within its own reality.

Venturing further into the in-between, Chi masterfully merges the space between the viewer’s “real” and the photo’s demi-fantasy. The weight of the bottom half bridges the distance between the viewer’s world and the photograph’s far-off shore. The photograph’s large portion of solid darkness creates a powerful illusion of depth. The black area seems to support the viewer—like she is standing right up against the mountain, forest, or building that domineers over the near side of the lake. Thus, the lifting light appears further and further away. The transparent, watercolor mountains seem to be of an unreachable, ephemeral space. In the middle of this, is Chi. Unaware of my existence, he teeters on the threshold between my changing, living reality and a far off, unplaced metaphor.

As I prepare to leave, I notice something standing in the lake’s glass reflection.

Me.

And others, and that Hollywood picture opposite the wall. We’re all there, sharing in the spectrum between our reality and that of the photograph’s. Though the photo’s imaginative space seems to exist, elevated above the ugly details of my time now, and his time then, I see that the two cannot be separated. Sitting in the glass of “Lake Ninevah, Vermont,” are also the reflections of his works in Hollywood, Checkpoint Charlie, and Brasilia. These too cannot be separated from his surrealist work; for ultimately, they are of the same of the origin. And finally, sitting in the glass of “Lake Ninevah, Vermont,” is the art museum.

560 Comments

lenti fotocromatiche

occhiali fotocromatici rayban sue

occhiali fotocromatici rayban

This is really interesting, You are an excessively skilled blogger. I have joined your rss feed and look ahead to in the hunt for extra of your great post. Also, I’ve shared your website in my social networks! جراحی زیبایی بینی طبیعی

Explore ggwinner app sleek design and effortless navigation. Enjoy a user-friendly interface, stunning visuals, and an intuitive layout. Join us today for a perfects!