Today, first year fellow Jason Arnold shared an unusual case of pulmonary cryptococcosis in a HSCT recipient.

Here are a few high yield points from our discussion:

Thanks, Jason!

Today, first year fellow Jason Arnold shared an unusual case of pulmonary cryptococcosis in a HSCT recipient.

Here are a few high yield points from our discussion:

Thanks, Jason!

This week in ILD conference, Tim presented a case of fibrotic interstitial lung disease in a middle-aged woman who was born and raised in India and has lived in the US for several years. The CT showed diffuse fibrotic changes with air trapping but no particular apicobasilar gradient. CHP was suspected but HP panels negative and no clear exposure had been identified.

Dr. Parekh inquired whether the patient ever participated in preparation of chapati, which Tim & Anthony had not yet discussed with the patient. On follow up with the patient, she has made chapati every day of her adult life. Interestingly, she had not been involved in chapati baking in last 4-6 months because of hand arthritis. Interestingly, this time course correlated with a previously unexplained improvement in her symptoms.

I. What is the typical radiographic pattern associated with hypersensitivity pneumonitis?

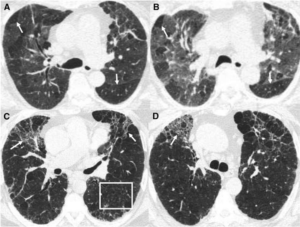

Key point: hallmark of HP is air trapping – expiratory imaging as obtained in HRCT is essential for detection. Air trapping (hypoattenuation), alongside ground glass and normally perfused unaffected lung produces the pathognomonic “three density” or “head cheese” CT finding in HP

Figure: https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/10.1164/rccm.201608-1675PP

Non-fibrotic Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis: groundglass opacities in random axial and craniocaudal distribution; small (<5mm) centrilobular nodules, air trapping/mosaic attenuation.

Fibrotic Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis: similar distribution and pattern with interposed reticulation, traction bronchiectasis +/- honeycombing. Fibrosis tends to spare basilar lung zones, distinguishing from UIP pattern

HP diagnostic approach:

II. Besides exposure remediation, what is the standard pharmacologic treatment for CHP?

Key point: immunosuppression is the mainstay of pharmacologic treatment for hypersensitivity pneumonitis with evidence of active inflammation

III. What is “baker’s lung” and in whom should we suspect it? How does this differ from hypersensitivity pneumonitis from occupational exposure to flour?

Baker’s Lung: One of the most reported occupational lung diseases in western countries. It is characterized by respiratory symptoms such as airflow obstruction and bronchial hyper-responsiveness that has been shown to develop in work environments in which there is continued exposure to bakery flour dust.

Hypersensitivity pneumonitis: As a separate entity, Hypersensitivity pneumonitis has been reported in occupational exposure to bread flour, related either to precipitins against A fumigatus itself (a common culprit for HP in farmers lung), the flour mite Acarus siro, or weevil infestation.

Works Cited:

https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.13-1734 https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/full/10.1513/AnnalsATS.202009-1195CME https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/10.1164/rccm.201608-1675PP https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4278578/#R1 https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/full/10.1164/rccm.202005-2032ST https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/009167499290470M

Patient in her 60s, former smoker 40py, with abnormal LDCT imaging. Some dyspnea but thought to be related to significant weight gain during pandemic.

Special shoutout to Dr. Agrawal’s Youtube channel and MIPs!

The case had a small endobronchial lesion on CT. We reviewed the differential for endobronchial lesions:

And focused on trahceobronchial tumors, which are rare, 0.6% of pulmonary tumors. (With a fun jeopardy matching series of slides, not captured in this post.)

DIPNECH – associated with bronchial carcinoid, consider in asthma patient with endobronchial abnormality.

Thanks for a great review and a fun interactive session, Dr. Rowe!

Timothy Rowe, MD, Pulmonary and Critical Care

On Monday, second year fellow Tom Bolig presented the course of a middle aged undomiciled man with heroin use disorder and recurrent severe asthma exacerbations. This patient had no history of peripheral eosinophilia or IgE elevation. He was non-adherent to maintenance inhaler therapy. He was admitted to the MICU after intubation for asthma exacerbation following unintentional heroin overdose.

This prompted a discussion of the entity of potentially fatal asthma (PFA), defined by Northwestern’s own Paul Greenberger (1,2)

Potentially fatal asthma (PFA) is a clinical condition wherein 1+ of the following are present:

Why is this so important?

Back to Tom’s patient – a NBBAL was performed with PMN predominance, non-pathologic growth on cx, strongly positive amylase and a galactomannan Ag of 3.87. CT imaging showed patchy bibasilar infiltrates, not consistent with invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (IPA).

What are the most recent recommendations on interpretation of testing in suspected IPA?

All of the following from 2019 ATS Guidelines (3) with strong recommendation/high quality evidence

Tom’s patient fell outside the best studied population (hematologic malignancy and transplant) for galactomannan testing for IPA, and suspicion for disease based off of CT evidence was low. Although this has not been described in the literature, Ben Singer raised the possibility of aspiration of fungal cell wall contents from oropharynx as a putative cause of transiently elevated BAL galactomannan.

Finally, Tom discussed “Mab” therapy for asthma, providing a quick reference chart that takes some of the guesswork out of determining indications:

Thanks, Tom!

Sources:

It’s been a few weeks since our most recent ILD roundup – we’re glad to be back! This weeks ILD conference was chock full of pearls as usual.

1. First, we discussed the implications of leukocyte telomere length (LTL) testing on decision to use immunomodulatory therapy. Recall that PANTHER-IPF showed evidence of harm in patients with IPF receiving prednisone, azathioprine and n-acetylcysteine (NAC).

Could LTL serve as a biomarker to predict patients at risk of harm from use of immunomodulatory therapy in IPF?

This question was asked in a recent post-hoc analysis1 of the PANTHER-IPF2 and unpublished ACE-IPF study. The authors found that short LTL (<10%ile) was associated with an increased risk of the composite outcome of death, lung transplantation or FVC decline in those exposed to prednisone/azathioprine/NAC (HR 2.84; 1.02-7.87, p=0.04). This association was not found in either cohort when patients with LTL >10%ile were examined.

The authors propose that this may be related to unmasking of an immune dysfunction phenotype in patients with short LTL through immunosuppression. When the same criteria were applied to an unrelated cohort of patients participating in a longitudinal observational study at UTSW, there was actually a significant improvement in the prednisone/azathioprine/mycophenolate group with LTL >10%ile.

Kaplan-Meier curve – UTSW cohort

2. Our next patient was a woman in her 70s with GERD and chronic joint pain. with CT imaging after mechanical fall concerning for ILD. Has developed progressive DOE over past year, with steroid responsiveness. The overall CT pattern was most consistent with fibrotic NSIP, but perilobular opacities were also noted. A differential consideration of organizing pneumonia3 was discussed.

What is a perilobular opacity?

A perilobular opacity refers to polygonal opacity around interlobular septa and with sparing of the secondary pulmonary lobule. As Dr. Agrawal brought up to the group, this tends to have more diffuse distribution than a a “reversed halo/atoll sign” which is a focal finding.

“Reverse halo”, or “Atoll” sign in organizing pneumonia

Perilobular opacity in association with bronchial wall thickening and bronchial dilation in organizing pneumonia

What are the radiographic features most consistent with organizing pneumonia, and what are their primary differential considerations?

3. A final case we discussed was a former tobacco user in his 70s, with RA on MTX, Humira and prednisone, former asbestos exposure, who presented to VA clinic with progressive DOE over past 6-12 mo. A transbronchial biopsy performed in 2021 with negative cytology for malignancy but otherwise non-diagnostic. CT with showed significant asbestos related pleural disease. Reticulation was seen mostly in association with pleural plaques. Despite the diagnosis of seropositive RA, our multi-disciplinary consensus was asbestos-related pulmonary fibrosis. The question of anti-fibrotic treatment was raised.

What is the evidence for antifibrotic therapy in asbestos-related pulmonary fibrosis?

Remember, the INBUILD4 trial showed evidence of benefit (lower annual rate of FVC decline) for antifibrotics in non-IPF fibrosing ILDs. Did they include asbestos-related fibrosis? Hard to say! Looking at the supplementary information (see Table below), 81/663 patients fell into category of “other ILDs” which did include exposure-related ILDs among others, but didn’t specifically mention asbestosis.

The RELIEF5 study was a phase II placebo controlled RCT that looked at use of antifibrotic agents for non-IPF ILDs (fibrosing NSIP, CHP, and asbestos related pulmonary fibrosis). Patients enrolled had experienced disease progression despite conventional therapy. Of note, only 5 of 127 patients included with asbestos-related pulmonary fibrosis. They followed patients for 48 weeks and reported a significantly lower rate of decline in FVC as a % of predicted value.

The annual rate of decline in FVC (-36.6 vs –114.4, p=0.21) did not meet statistical significance. Why is this relevant? A quick refresher6 on the endpoints for the IPF anti-fibrotic trials:

Sources:

At ILD conference this week, a patient with progressive RA-ILD was discussed. A change in the patient’s rheumatoid arthritis medication was to be determined with her rheumatologist, but she was also recommended to start nintendanib

I. What is the evidence for anti-fibrotic therapy outside of IPF?

Prior to 2019, the efficacy of antifibrotic therapy in non-IPF fibrosing lung disease was unknown. INBUILD was a double-blind, placebo controlled RCT to investigate the efficacy of antifibrotic therapy in non-IPF fibrosing lung disease.

Let’s approach this study using the PICO framework!

Population:

All patients had to meet criteria for progression of ILD in the past 24 months despite treatment with an FVC =< 45% and DLCO <80%.

Breakdown of population by diagnosis:

·

·

Intervention:

Nintedanib 150mg BID

Comparison:

Placebo

Outcomes:

The patient population was stratified by ILD with or without a UIP pattern of fibrosing ILD. Nintendanib decreased the rate of decline in FVC regardless of the pattern of fibrosis in this patient population.

The patient population was stratified by ILD with or without a UIP pattern of fibrosing ILD. Nintendanib decreased the rate of decline in FVC regardless of the pattern of fibrosis in this patient population.

In another case, our thoracic radiologist Dr. Parekh pointed out an example of dendritic pulmonary ossification.

II. What is dendritic pulmonary ossification (DPO)?

Top: neuron with dendrites

Bottom: coronal view of CT showing dendritic pulmonary ossification

Sources:

Thanks to our fearless leader Dr. Schroedl for presenting an interesting case of pulmonary MALT lymphoma!

Young woman with chest pain and dyspnea – left upper lobe lesion that didn’t respond to empiric treatment for CAP or even an empirical treatment for fungal pneumonia (unknown exact regimen). Bloodwork and noninvasive infectious workup were unrevealing. Initial bronchoscopy and biopsy were unrevealing. Repeat imaging six months later showed persistence of left upper lobe mass.

The patient got a repeat CT-guided biopsy that showed MALT lymphoma! This is a rare disease, and an extranodal low-grade B-cell lymphoma.

Treatment: ritxumab

The patient had good imaging response but persistent dyspnea, which is thought to be asthma that upon further probing, seemed present even prior to these.

Nice review article here: https://erj.ersjournals.com/content/34/6/1408

Thanks, Dr. Schroedl!

Clara Schroedl, MD, MSc, Medicine – Pulmonary/Critical Care

This week, we discussed the case of a 48 yo with chronic cough who presented to care for evaluation of abnormal CT chest, which showed multifocal peripheral and peribronchovascular pulmonary nodules.

I. How can we use distribution of nodules to narrow differential diagnosis?

Back to our patient! Using our knowledge and the peribronchovascular/subpleural distribution of nodules, a focused differential diagnosis was discussed (sarcoidosis, silicosis/coal-workers pneumoconiosis, lymphangitic carcinomatosis). Absent occupational exposures were noted, and lack of associated adenopathy/effusions/extrathoracic disease was discussed. Bronchoscopy with EBUS/TBNA and TBBx was performed. A representative sample of the transbronchial biopsy is shown below:

Transbronchial biopsy showing tightly packed non-caseating granulomas with partial hyalinization in a peribronchial distribution compatible with nummular sarcoidosis

Based on the CT and biopsy findings, the group arrived upon a diagnosis of nummular sarcoidosis. Given relatively mild symptoms and normal pulmonary function tests, Dr. Russell suggested the use of high dose inhaled steroids.

II. What is the role of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) in the management of sarcoidosis?

The rationale for use? Sarcoidosis is a disease process that follows a lymphatic distribution in the lungs – ICS targets the endobronchial lymphatics. In short, the data is limited! A Cochrane review of corticosteroid use in sarcoidosis included 7 studies that assessed ICS (budesonide 800-1600 mcg/d or fluticasone 880-2000 mcg/d) use, specifically in patients with stage 1 & 2 disease. No improvements in CXR or PFTs were observed, although one study showed a modest improvement in DLCO/VA and others reported improvement in symptom scores.

III. What are the extra-pulmonary screening recommendations in sarcoidosis?

Sources:

Sources:

Last week in Grand Rounds, 3rd year fellow Romy Lawrence treated us an update on the latest advances in Pulmonary Hypertension.

The graphic below provides a helpful organizer for the three physiologic categories of PH: pre-capillary (Pre-PH), combined pre-and-post capillary (Cpc-PH), and isolated post-capillary (Ipc-PH)

Another common characterization for PH is WHO category. As a reminder of categories:

First, how did the 2022 ESC/ERS update change from the 2018 WSPH Guidelines?

The PVR cutoff was changed to 2! This was decided as it was roughly the cutpoint above which an increased hazard ratio for mortality was observed in the CART cohort. An important point here – these do not yet translate to therapeutic recommendations, as efficacy of PH therapy between mPAP 21-24 and 2-3 WU remains unknown.

So if the new cutoffs haven’t resulted in updates in therapeutic recommendations, what do we do with them??

The entity of exercise PH, defined as a mPAP/CO slope between rest and exercise >3 Hg/L/min, was also defined.

A really important point here – symposia have been exclusively held in affluent countries, despite the fact that most of the global PH burden is in low and middle income countries. What implications does this have for focus of therapeutics, imaging, advocacy?

A really important point here – symposia have been exclusively held in affluent countries, despite the fact that most of the global PH burden is in low and middle income countries. What implications does this have for focus of therapeutics, imaging, advocacy?

Here’s a broad overview by WHO group:

Romy reminded us that the mainstay of PAH therapy is to target one of three pathways known to be implicated in the pathogenesis of PAH: (1) excessive endothelin-1 production, (2) deficient prostacyclin, and (3) low nitric oxide production.

Romy reminded us that the mainstay of PAH therapy is to target one of three pathways known to be implicated in the pathogenesis of PAH: (1) excessive endothelin-1 production, (2) deficient prostacyclin, and (3) low nitric oxide production.

After vasoreactivity testing and CCB trial if applicable, the most important determinant of treatment is risk assessment (REVEAL score or ESC/ERS risk stratification). An algorithmic approach from there:

The risk calculator is linked below if you’d like to learn more!

PAH in the pregnant woman – an uncommon situation with extremely high (30-50%) mortality. The WHO recommends against pregnancy in PAH. We also discussed the following:

3 criteria for CTEPH:

What is the relationship between acute PE and onset of CTEPH?

Important to know that certain factors increase the likelihood of CTEPH. These include some unsurprising conditions, such as prior PE (OR 19) especially unprovoked (OR 5.7).

Less intuitive – splenectomy (OR 18), ventriculo-atrial shunt or infected pacemaker (OR 76!!)

Finally, an overview of CTEPH treatment pathways:

Balloon pulmonary angioplasty (BPA) is used in distal or surgically inaccessible disease, and/or in patients for whom comorbidities preclude surgery. This is done in series of 4-6 sessions separated in time by several weeks.

Riociguat is approved for use in medical management of inoperable CTEPH based off of the CHEST trials.

The role of medical therapy as a bridge to surgery or BPA is less certain, given that it may delay appropriate referral and expedited treatment.

Thanks for an outstanding Grand Rounds, Romy!

Sources