This week in ILD conference, Tim presented a case of fibrotic interstitial lung disease in a middle-aged woman who was born and raised in India and has lived in the US for several years. The CT showed diffuse fibrotic changes with air trapping but no particular apicobasilar gradient. CHP was suspected but HP panels negative and no clear exposure had been identified.

Dr. Parekh inquired whether the patient ever participated in preparation of chapati, which Tim & Anthony had not yet discussed with the patient. On follow up with the patient, she has made chapati every day of her adult life. Interestingly, she had not been involved in chapati baking in last 4-6 months because of hand arthritis. Interestingly, this time course correlated with a previously unexplained improvement in her symptoms.

I. What is the typical radiographic pattern associated with hypersensitivity pneumonitis?

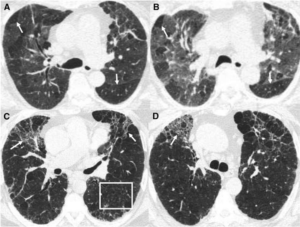

Key point: hallmark of HP is air trapping – expiratory imaging as obtained in HRCT is essential for detection. Air trapping (hypoattenuation), alongside ground glass and normally perfused unaffected lung produces the pathognomonic “three density” or “head cheese” CT finding in HP

Figure: https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/10.1164/rccm.201608-1675PP

Non-fibrotic Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis: groundglass opacities in random axial and craniocaudal distribution; small (<5mm) centrilobular nodules, air trapping/mosaic attenuation.

Fibrotic Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis: similar distribution and pattern with interposed reticulation, traction bronchiectasis +/- honeycombing. Fibrosis tends to spare basilar lung zones, distinguishing from UIP pattern

HP diagnostic approach:

II. Besides exposure remediation, what is the standard pharmacologic treatment for CHP?

Key point: immunosuppression is the mainstay of pharmacologic treatment for hypersensitivity pneumonitis with evidence of active inflammation

- Initial tx with corticosteroid

- 0.5-1 mg/kg/d pred or equivalent, taper to 20 mg/d within 3 mo with close follow-up of PFTs, 6MWD and clinical response

- When to consider cytotoxic agent (MMF, AZA)

- Up front with steroids if antigen not readily identifiable

- Maintenance if response to steroids depending on remediation of antigen, side effect tolerance

- Antifibrotic treatment in patients with chronic fibrosing ILDs with a progressive phenotype (FDA approved based on INBUILD data)

III. What is “baker’s lung” and in whom should we suspect it? How does this differ from hypersensitivity pneumonitis from occupational exposure to flour?

Baker’s Lung: One of the most reported occupational lung diseases in western countries. It is characterized by respiratory symptoms such as airflow obstruction and bronchial hyper-responsiveness that has been shown to develop in work environments in which there is continued exposure to bakery flour dust.

- Suspect Baker’s lung in anyone with an occupational or recreational exposure to large quantities of freshly baked breads (bakers, pastry chefs, confectioners, etc.) and asthma-like symptoms.

- Baker’s lung is caused by Aspergillus-derived carbohydrate cleaving enzymes (ex: alpha-amylase) commonly used to enhance baked products.

Hypersensitivity pneumonitis: As a separate entity, Hypersensitivity pneumonitis has been reported in occupational exposure to bread flour, related either to precipitins against A fumigatus itself (a common culprit for HP in farmers lung), the flour mite Acarus siro, or weevil infestation.

Works Cited:

https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.13-1734 https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/full/10.1513/AnnalsATS.202009-1195CME https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/10.1164/rccm.201608-1675PP https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4278578/#R1 https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/full/10.1164/rccm.202005-2032ST https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/009167499290470M

·

· The patient population was stratified by ILD with or without a UIP pattern of fibrosing ILD. Nintendanib decreased the rate of decline in FVC regardless of the pattern of fibrosis in this patient population.

The patient population was stratified by ILD with or without a UIP pattern of fibrosing ILD. Nintendanib decreased the rate of decline in FVC regardless of the pattern of fibrosis in this patient population.

Sources:

Sources: