Author: Drew Miller (Weinberg ’23)

For die-hard football fans, nothing beats the feeling of sitting back on a Sunday and wasting the day on the couch watching football. In an attempt to see the best action, most fans will flip through the one o’clock and four o’clock games and watch a few plays from every game. However, there are three games a week that have everyone’s full attention, where there is no flipping the channel, where there is no missing out on a single play: NFL Primetime football. These games, played every Thursday, Sunday, and Monday night, are the games of the week. And with this, network viewership, Quarterback and general team performance are put under a microscope. These games impact public perception of quarterbacks, and fans and media alike often draw misguided conclusions from these games. Using a spatial model of primetime quarterback play, I show the reasoning behind the hot takes about these players. Further, I use a spatial model of playoff quarterback play as a comparison to the first spatial model, employing differences to explain widespread ideas about players. Lastly, using a linear model, I prove that there is no connection between primetime quarterback performance and playoff quarterback performance, showing that we shouldn’t be magnifying the primetime. Fans view the primetime as a preview to the playoffs, leading to unfair opinions and wrong conclusions about players.

The problem is simple: we talk too much about primetime games and too little about the regular NFL games. This is a systematic problem, with broadcasters, the media, fans, and the television deal between DirecTV and the NFL all playing a part.

Broadcasters in sports love to push narratives; stories help explain to casual viewers what is happening and add intrigue to games. A week-two game between two good teams will always garner high ratings, but the addition of the narrative of a Super Bowl preview can make the game seem more important and more interesting. Broadcasters will try to add any narrative that adds importance to a game. For example, announcers love games between Tom Brady and a good young quarterback, as they can push the idea of a young challenger to the older, established star. This is the same across all sports–you cannot watch a Lakers game without hearing about LeBron and the other team’s young star potentially taking his throne.

Further, the media drive this narrative home. There are primetime games Thursday, Sunday, and Monday night. Many sports talk shows and debate shows open their Friday, Monday and Tuesday morning shows with conversation about the previous night’s primetime game. This is not necessarily the media’s fault, as it makes sense to cover the game everyone has watched, but their need for ratings leads to unnecessary hot takes, exaggerating the importance of the primetime game from the night before. Fans that watch these shows then take these opinions as gospel, creating widespread false narratives about players.

All of these factors come down to the NFL television deal with DirectTV. In this deal, DirectTV has exclusive rights to all non-primetime NFL games. This means fans can only watch the two locally televised games during the day and then have full access to the primetime games. With the high price of DirectTV, and the high price of the Sunday Ticket Package to gain access to every game, many fans practically only watch primetime games.

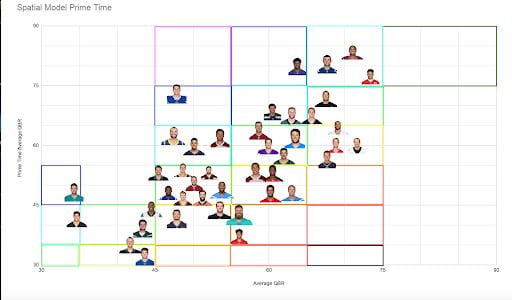

To address this, I created the model above. With the two axes, I create groupings or categories of quarterbacks that can tell us about their play. I used ESPN’s standards for QBR rating to create the categories, with 75+ as the top category, 65-75 as elite, 55-65 as good, 45-55 as average, 35-45 as below average, and 35 and under as poor. My model is color-coded, as the green boxes are for players that fall into the same category for both the normal games and the primetime. Turquoise is for players performing one category above their standard play, blue for two, and purple for three. Conversely, for players performing worse in the prime time than their average, it goes yellow, orange, red, and black. Taking every NFL starting quarterback and placing him in the spatial model, we can see which players fit into which categories, breaking previously held public ideas and opinions about players.

From the spatial model, a few aspects are immediately obvious to a true sports fan. Kirk Cousins is often degraded as a player who can’t play in the bright lights, and it is widely questioned if he is a true franchise quarterback because of this perceived quality. The narrative is that he is a good quarterback but can’t get it done when it matters most. Looking at the model, Cousins is in a green box for the good category, with an almost equivalent QBR in primetime and regular game. Cousins plays just fine in the primetime, and he is unfairly critiqued based on his team’s relative failures in those games. Further, Tom Brady falling to the bottom of the yellow category might seem surprising. Widely considered one of the greatest of all time, Brady underperforming in the primetime seems to contradict my thesis and his GOAT status. However, much of the Brady criticism comes directly after his primetime blunders, as the media loved to call the Patriots dynasty dead after a bad primetime game from Brady. Following a bad 2014 Patriots Monday night loss to the Chiefs, Grantland writer Bill Barnell called for the end of the Patriots; the Patriots ended the season one game away from the Super Bowl. History repeated itself in 2017, as the Patriots lost the first primetime game of the year to the Chiefs 42-27 and great criticism followed; the Patriots won the Super Bowl in 2017. This happened consistently, as Brady and the Patriots seemingly loved to perform poorly in the primetime, garner criticism, and then prove the critics wrong. More phenomena can be explained by the spatial model–the lack of Drew Brees respect could be partly explained by his standing in the yellow box, the love of Carson Wentz (turquoise) and the question marks surrounding Jimmy Garapolo (yellow) could be explained by their relative primetime performances. The Lamar Jackson bandwagon of 2019 could be more understood with his place in the blue box. When more people are watching, as in the primetime, more opinions are formed.

I created this second model to contrast the first model, as we can now see which quarterbacks fit into the different categories in the different games. The addition of the second spatial model can further explain the Brady phenomena. Brady, as stated in the first spatial model, is in the yellow category in the primetime and garners significant criticism following these games. However, Brady is still considered the greatest of all time by many. In the model above, Brady, who has played the most playoff games of any quarterback in the past four years, is in the green box with a superb playoff QBR. Brady’s playoff and primetime QBR disparity explain both his status as the GOAT and the harsh criticism he receives during the season. Again, the Kirk Cousins myth is exposed. Cousins plays well in both the primetime and playoffs, he is in the green zone in the primetime and turquoise in the playoffs. The question marks surrounding his big-game play are unfair and not supported by the data. Young stars Deshaun Watson and Lamar Jackson have the largest gaps between their primetime play and playoff play, as both players have played like top five quarterbacks in primetime but have largely struggled in the playoffs. These playoff failures can partially explain the widespread criticism and jokes about Lamar Jackson, as in the two most important games of his career, he has barely eclipsed a 20 QBR. Their performance is a stark contrast to Patrick Mahomes and the older star quarterbacks in the league–the two need some time to grow into true stars. Lastly, there is some visual evidence that teams don’t need a great quarterback to make the Super Bowl. Jimmy Garappolo has been well below average in the playoffs, and the 49ers still made the Super Bowl last year. The same is true with Jared Goff the year prior: good teams can overcome somewhat poor playoff quarterback play. However, neither of those two teams won the Super Bowl.

The linear model above suggests that no significant correlation exists between primetime quarterback play and playoff quarterback play. Primetime performance is not one of the factors that impact or predict playoff performance. Many of the conclusions and hot takes from the media and fans over the course of the year suggest the legitimacy of this fallacy, as they imply that these big primetime games impact the playoffs more than any other, regular game.

These three models work in conjunction to suggest that the primetime football games are focused upon too heavily and that different quarterbacks perform well in the playoffs and in primetime. Of course, the great quarterbacks will perform great in both settings, but it is interesting to see which players elevated their games in these two settings. The spatial models allow us to see the differences in which quarterbacks are in which categories, with the truly great quarterbacks like Brady, Mahomes, and Russell Wilson excelling in the playoffs, while there is more variation in which type of quarterbacks are best in the primetime. Of the quarterbacks with the biggest positive jumps in the primetime, most are young rising star quarterbacks like Lamar Jackson and Deshaun Watson; these are also the guys without the biggest decrease in performance in the playoffs. The first two models help explain the phenomena around these players and how we think about them. The linear model suggests that there is no connection between primetime and playoff quarterback performance, and that while the primetime marquee matchups are fun to watch, they are not as predictive as narratives makes them out to be.

Be the first to comment on "Prime Time Games Drive Narratives, Not Future Playoff Success"