The following post by Austin Benedetto, an undergraduate student at Northwestern University, is the first in a new series of posts highlighting exemplary work by undergraduates with interests in Russian Philosophy and Religious Thought. The NURPRT Forum welcomes any undergraduate student to submit academic writing related to these fields to be considered for publication.

Walk into any bookstore, and one will see countless titles advertising the best way to live, steps to follow, or paths to take. There is so much writing in this genre that it now has its own name: “how-to” books. Unfortunately, while many of these books have useful lessons and principles, much of life is idiosyncratic. What helps one person may be neutral or negative for another.

While “how-to” is often tailored individually, “how-not-to” is more universal. The contemporary philosopher Susan Wolf posits that most people agree that inaction and sloth are bad. Yet, many people fall into laziness; they never quite accomplish or act in the ways they wish. Anecdotally, I have met many people who have read books like Atomic Habits, talked about how they were going to make big changes, and then did nothing. These books can be useful, but real intellectual change most often comes from more emotional and enigmatic motivations. As the Underground Man, the protagonist from Dostoevsky’s Notes from the Underground, states:

Reason is only reason and satisfies only man’s reasoning capacity, while wanting is the manifestation of the whole of life.[1]

There is much truth to these musings. It is easy to intellectualize about making change; it is, however, very hard to actually change a habit through pure logic. Many people know of things they should improve upon (e.g., being more active), but most people act “against [their] own reason.”[2] The Underground Man attributes such decision making to humanity’s need to live “according to our own stupid will.”[3] People, he claims, value their individuality above all else and will act destructively on purpose in order to reaffirm their individual agency.

This is a compelling account of human behavior. However, it is also important to note that man is a “creating animal.”[4] As Ernest Becker writes in the Denial of Death, humans take on “immortality projects” in order to deny death.[5] People create to distract themselves from their mortality. There are two factors here: the need for individuality and the fear of loss. Both play an important role in human motivation. Yet, the Underground Man makes clear that creativity is not a wholly successful means of distraction. A person in the throes of erecting something new is nevertheless “instinctively afraid of achieving the goal and completing the edifice he is creating.”[6] By achieving a goal, there is no more work to be done. One might as well be dead – the never-ending goal of self-assertion is lost. This is a more nuanced fear of loss: the fear of losing something to do.

This debilitating fear is also where the “how-not-to” part of Notes from the Underground becomes apparent. When describing the story of Adam, Soren Kierkegaard writes that freedom constitutes “the anxious possibility of being able.”[7] This anxiety is what, often deplorably, drives the Underground Man. He is overwhelmed by the responsibility that comes with the infinite possibilities of life; instead of taking risks and actively doing, he intellectualizes and thereby never accomplishes much. Even in the rare moments where he breaks from his otherwise disembodied existence, he spends most of his time before and after in a state of tortured fretfulness about what comes next. In anticipation of going to a dinner with old schoolmates he begins to pray “in inexpressible anguish” to “God for that day to pass more quickly.”[8] Just the idea of a change in routine crushes him. The closer he comes to real, unpredictable action, the further he plunges into inaction – into the underground.

There is perhaps no better evidence of the Underground Man’s anguish than his post-dinner cab ride to confront the person he had just drunkenly challenged to a duel. During the short journey, he raves about all that will happen at this confrontation until he begins to weep and realize “that all this [his ravings] came from Silvio and from Lermentov’s Masquerade.”[9] There is nothing original to his fantasies. His visualization of the duel is derivative of a well-known play. When confronted with novel and unknown possibility, he resorts to thinking in “literary” terms.[10] He imagines the future as if it were a pre-written story unfolding. In books, the conclusion is already foregone; contingency and possibility are absent: there is no risk and uncertainty. His move to a “literary” notion of time and space is a coping mechanism to avoid the uncertainty inherent to the actual world of flesh and bone. The risk of failure inherent to free, embodied action leads the Underground Man to see “living life almost as labor” – as “drudgery.”[11] Therefore, he speculates that “[humans] all agree in ourselves that it [life] is better from a book.”[12] These thoughts stem from the fear of losing his personhood, but, even more poignantly, they exemplify his anxiety of a non-literary world: a world in which he can toil and still fail.

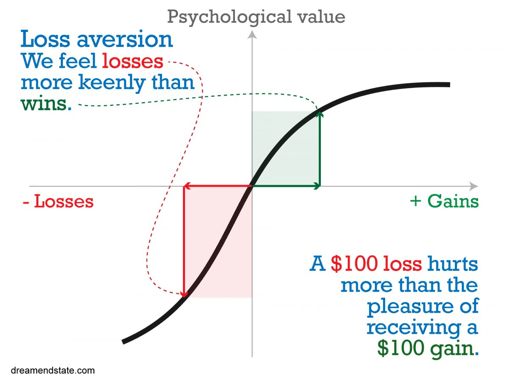

Is it true that we all share this fear of uncertainty? Is it true, furthermore, that the “direct, lawful, immediate fruit of consciousness is inertia” and inaction?[13] As Dostoevsky writes in a footnote to the novella: “the author of the notes,” while “fictional,” is a “representative of a generation that is still living out its life.” Dostoevsky believes the Underground Man’s anxiety to be a widespread issue, and more recent studies confirm his intuition. Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, two highly-lauded economists, published their influential paper on “Prospect Theory” in 1979.[14] The paper contended that people do not always act in accord with a rational theory; instead, they are motivated at a more fundamental level by “loss aversion” – the principle that people are distressed more by losses than they take pleasure in equally sized gains.

This finding, I submit, can help explain the Underground Man’s predicament and illustrate what the reader can learn from his limitations. Hardwired into all of us is a desire for certainty. And in the event of a potential loss, even if the reward is potentially greater, humans often shun the bet and live metaphorically in the underground. This anxiety can be crippling and leads to poor decisions – and to inertia and stagnation. To venture above-ground, it is vital to push ahead even if we can never leave behind this innate shortcoming.

Kierkegaard writes: “Whoever has learned to be anxious in the right way has learned the ultimate.”[16] While he writes in the context of religion, the idea can be applied agnostically. Acknowledging uncertainty and the potential for loss is essential in understanding the human condition, but this should not lead to inaction. It is important to take charge and deal with the consequences. The Underground Man has learned to be anxious, but he has done so incorrectly:

And now I am living out my life in my corner, taunting myself with the spiteful and utterly futile consolation that it is even impossible for an intelligent man to become anything, and only fools become something.[17]

Even the Underground Man acknowledges that his reasoning is “futile.” He is addicted to a simplified Darwinian approach to thought and life – a viewpoint which conveniently helps him avert individual loss altogether. He is so scared of the flesh, mortality, and uncertainty that exist above ground that he believes “it’s a burden for us even to be men—men with real, our own bodies and blood.”[18] By living in a state of inaction, he has foolishly attempted to leave behind his body and escape into the world of the mind where he can toil endlessly. This is the root of his problem and also evinces what he fears most: reconciliation with an active, socially-engaged life. Sociality, for the Underground Man, represents a place of disrespect and violence. He cannot get beyond “loss aversion” because he sees every interaction as one of mutual contempt; he fails to understand that people are capable of mutually acknowledging each other’s dignity.

One of the more prescient passages from the Notes has the Underground Man frustrated from the competition which, in his view, encompasses all social interaction: even something as simple as traversing public areas. Whenever the Underground Man walks by a seemingly successful man on the sidewalk, he always steps aside, allowing the other man to pass. He judges – probably incorrectly – that he is being disrespected and ignored by this pedestrian. Then, after weeks of scheming about how he is going to avenge this – maybe imagined – slight, the Underground Man “at the very last moment, at some two inches away, moved aside.”[19] His fears and constant thinking continue to stunt him for some time until “suddenly, within three steps of my enemy, I [the Underground Man] unexpectedly decided, closed my eyes, and–we bumped solidly shoulder against shoulder!”[20] This passage may seem absurd. However, it is only when he closes his eyes and just does that he can finally assert his dignity as a person. This demonstrates the dilemma of the Underground Man. He assumes the above-ground world to be cruelly abundant with potential pain and failure; yet he still wishes to assert himself as an individual. It is only when he stops thinking about the consequences of action that he can claim to be dignified.

This fear of embodied action is more potently manifested in the final scene of the Notes, when Liza, a woman who the Underground Man drunkenly told to come to his house, actually arrives. This surprise leaves him in such a frenzy that he lashes about, belittling himself in a fit of verbal self-flagellation. The Underground man believes social existence to be a zero-sum game and so rejects any possible further relation with her. Then, when she departs, he subsequently chases her in vain. Finally, after all this occurs, he rationalizes the insult of the event as “purification” and the “most stinging and painful consciousness!”[21] To be a conscious individual, for the Underground Man, is to be constantly insulted. This, however, is the viewpoint that Dostoevsky and the economists, Kahneman and Tversky, are warning against. Just because bodily life does come with unknowns and the potential for failure and loss, does not mean it only has rejection. As Kahneman’s graph makes clear, people get wound up overemphasizing the negative and consequently forego sound decision-making. When a person enters the social domain, they may err, but even these failures can be fruitful and worthwhile.

The Underground Man is so scared of losing his secure – even if dangerous and inaccurate – domain of thought that he becomes addicted to living in the shabby edifice of the underground. Whenever he has a moment of potential salvation, he immediately returns to what he knows best: inactive intellectualization; unfortunately, this leads to more crippling anxiety and inertia. Instead of overthinking, it is vital to escape the hyper-negative mindset of the underground, take risks, and reconcile with the communal aspect of life. Moreover, this reconciliation is not an undoing of conscious thought; instead, novel, lived experiences often lead to true consciousness, dignity, and the right form of anxiety.

Notes serves as a critique of Cartesian doubt, science, and logic, all of which are often instinctively lauded in modern times. As Aristotle said: “man is by nature a social animal,” and it is self-defeating to ignore this vital aspect of life.[22] To learn and be human, one cannot – like Descartes – deduce life’s principles alone in a room; rather, one must live outside with people in the bodily world. A person can be thoughtful while also taking risks – after all, it is through uncertain action that one is dignified. It is from stories like this one that one can see how not to live. Notes from the Underground is a warning about the negatives of inaction, fear, and overthinking; the novel, however, leaves the journey above ground to the reader.

Austin Benedetto is a Northwestern undergraduate student majoring in Economics. His interests include a wide range of literature and philosophy but is the most intrigued by the 19th century Russian authors. He is currently focused on questions regarding emotivism, suffering, and how Russian literature helps address the problem of meaning and death in modern thought.

Image: Abraham Manievich, The Early Spring 1913

[1] Fyodor Dostoevsky, Notes from the Underground. Translated by Larissa Volokhonsky and Richard Pevear. (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1993), 28.

[2] Dostoevsky, Notes from the Underground, 22.

[3] Dostoevsky, Notes from the Underground, 25.

[4] Dostoevsky, Notes from the Underground, 30.

[5] Ernest Becker, The Denial of Death (New York: Free Press, 1973).

[6] Dostoevsky, Notes from the Underground, 33.

[7] Soren Kierkegaard, The Concept of Anxiety. Translated by Reidar Thomte. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1980): 44.

[8] Dostoevsky, Notes from the Underground, 71.

[9] Dostoevsky, Notes from the Underground, 86.

[10] Dostoevsky, Notes from the Underground, 50.

[11] Dostoevsky, Notes from the Underground, 131.

[12] Dostoevsky, Notes from the Underground, 131.

[13] Dostoevsky, Notes from the Underground, 17.

[14] Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, “Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision Under Risk” (Econometrica 47, no.2, 1979): 263-291, https://doi.org/10.2307/1914185.

“Prospect Theory” has since become the most cited economic article of all time.

[15] Ivan Edwards, “Prospect Theory: an ‘S’ curve and the relatively muted joy of winning,” Dream End State, February 15th, 2021, https://dreamendstate.com/2021/02/15/prospect-theory-why-we-feel-losses-more-intensely-than-gains/.

[16] Soren Kierkegaard, The Concept of Anxiety. 155.

[17] Dostoevsky, Notes from the Underground, 5.

[18] Dostoevsky, Notes from the Underground, 132.

[19] Dostoevsky, Notes from the Underground, 56.

[20] Dostoevsky, Notes from the Underground, 56.

[21] Dostoevsky, Notes from the Underground, 130.

[22] Aristotle, Aristotle’s Politics. Translated by Benjamin Jowett and H. W. Carless Davis. (Oxford: Clarendon Press: 1920): 1253a.