By Lewis J. Smith, MD

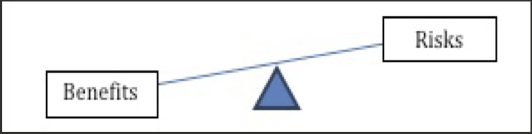

Human subjects are used in research to gain scientific and medical knowledge that can help others, and for collecting data that cannot be obtained using other means such as in vitro or animal experiments. In the research setting, human subjects are defined as living individuals from whom an investigator obtains data through intervention or interaction with the individual, or identifiable private information [1]. The potential consequences of research involving human subjects impact both the volunteers as well as society. The subjects may take on physical, emotional and financial risks but may also increase their access to counseling, medical care, medications and devices. Provided the study is scientifically sound, society benefits from increased medical knowledge. When deciding whether to pursue research with human subjects, a determination must be made as to whether the potential benefits to the subject and society exceed the potential risks, which are mostly borne by the subject (Figure 1).

Health care providers (e.g., physicians) engaged in human subjects research need to recognize that providing patient care and performing research on that same patient, are two different responsibilities. Patient care focuses on the individual and not doing harm; research focuses on generating generalizable knowledge and doing good. When involving human subjects in research, a research team must adhere to a set of regulations and guidelines that are based on several ethical and scientific principles.

What principles underlie clinical research?

Emanuel and colleagues listed several principles they considered to be central to clinical research (Table 1) [2]. First, the research must have value; providing enhancements of health or knowledge. Second, the research must have scientific validity, and thus must be methodologically rigorous. Third, there must be fair subject selection. This means that scientific objectives and the distribution of potential risks and benefits, but not vulnerability or privilege, should determine the inclusion and exclusion criteria for individual subjects. Fourth, there must be a favorable risk-benefit ratio that minimizes risks and maximizes potential benefits. Fifth, the research must go through independent review in which unaffiliated individuals review the research proposal in order to approve, amend or terminate it. Sixth, there must be informed consent, which is truly informed and voluntary. And last, there must be respect for enrolled subjects. This includes protection of individual privacy, the opportunity to withdraw from the research at any time and for any reason, and careful monitoring of the well-being of research participants.

Fulfilling these principles requires trained, experienced research teams composed of investigators, coordinators, technicians, data managers and more. Additional requirements include scientific review of the proposed research as well as review by an ethics committee. In the United States, the ethics committee is called the Institutional Review Board (IRB). An IRB must have at least five members, including a person not affiliated with the institution and a non-scientist, who collectively have the expertise to evaluate the proposed research. Northwestern University (NU) currently has six panels; five that review predominantly biomedical research, and one that reviews mostly social and behavioral research. These IRB panels review the human subjects research performed at the University and its clinical affiliates, including Northwestern Memorial Hospital (NMH), the Northwestern Medicine Group (NMG), and the Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago (RIC). Agreements also exist with Lurie Children’s Hospital (LCH) and other institutions to review human subject research performed at NU, and for NU to review research done elsewhere.

Once a project is approved by the IRB, researchers must adhere to the approved protocol. If unanticipated harm or risk to subjects arises during the study, the IRB must be informed immediately so that it can re-examine the protocol and review its previous risk-benefit determination. If an investigator modifies an approved protocol, IRB approval is required before the change is implemented.

How did we arrive at these principles: A brief history of Good Clinical Practice

The ethical principles noted by Emanuel et. al. are derived from a series of documents (Table 2) dating back more than 60 years, starting with the Nuremberg Code in 1947 [3] and followed by the Declaration of Helsinki in 1964 [4], the Belmont Report in 1979 [5], the Common Rule in 1991 [6], and the International Conference on Harmonization – Good Clinical Practices guidelines in 1996 [7]. These documents were created in response to an event or series of events that involved unethical or questionably ethical research practices. Some examples and a brief description of the regulations and guidelines follow.

During the Nazi medical experiments, Nazi physicians performed multiple, high-risk research studies on political prisoners and persons in concentration camps. One example is the hypothermia experiments designed to identify how best to decrease mortality in German aviators whose planes were shot down and were successfully rescued from the cold waters of the North Sea and North Atlantic, but then died from hypothermia. To identify the best method of rewarming, the Nazi doctors took individuals, put them in ice baths to produce severe hypothermia, and subjected them to various types of warming. Many of the individuals died during the experiments. These and other studies performed on human subjects by the Nazis during World War II led to the famous “Doctors Trials”, which culminated in the conviction of several physicians and death penalty for several of them.

The lessons learned from the Nuremberg Trials led to the Nuremberg Code. About 15 years later, the Nuremberg Code was the basis for the Declaration of Helsinki, an internationally recognized set of principles that still serves as a framework for research involving human subjects. Subsequent revelations about other research studies including, but not limited to, the Willowbrook Hepatitis Studies [8] and the Public Health Services Syphilis Study in Tuskegee [9] led to the Belmont Report and the Common Rule.

The Belmont Report is a seminal publication that articulates three essential ethical principles: respect for persons, including individual autonomy, protection of vulnerable populations, and informed consent; beneficence, meaning favorable risk-benefit assessment, quality of the study design, and qualifications of the investigator and associates; and justice, or the equitable distribution of risks and benefits. Yet, even after the Belmont Report was published and federal regulations implemented, examples of unethical research continued to appear on a regular basis. The Breast Cancer Studies in South Africa [10] is one example. A South African physician presented and published data in the 1990s indicating that adding an autologous bone marrow transplant to high-dose chemotherapy in women with metastatic breast cancer was superior to high-dose chemotherapy alone [11]. The initial reports were publicized widely and led advocacy groups to demand that this novel therapy be approved and covered by medical insurance in the United States. Under intense pressure, some insurance companies provided coverage, while others did not because they believed there was insufficient data to support this treatment. A large, multi-center study was initiated in this country to address the issue, but recruitment was slow as many women with metastatic disease were unwilling to be randomized to an arm lacking bone marrow transplantation. In the end, the investigator was cited for failing to obtain approval of the study before it was initiated, and for misrepresenting his findings. Subsequent studies showed that for most women the outcome was worse in those who received the bone marrow transplant.

Another example is that of Dr. Fiddes [12]. Dr. Fiddes was the president of a clinical research company in California. He conducted over 200 studies for scores of pharmaceutical companies beginning in the early 1990s. Many of the studies were used to support New Drug Approval applications (NDA) to the FDA. In 1997 he pleaded guilty to a felony charge of conspiracy to make false statements to the FDA in connection with the drug approval process. He was sentenced to federal prison, fined, and disqualified as a clinical investigator by the FDA because he made up fictitious research subjects, fabricated lab results by substituting clinical specimens and manipulating laboratory instrumentation, and manipulated clinical data by prescribing prohibited medications. None of these fraudulent practices were identified by either the company study monitors or the FDA inspectors that visited his research facilities multiple times. When the fraud was discovered, FDA inspectors asked Dr. Fiddes if the external study monitors and inspectors could have detected the fraud in some way. His response was they never would have detected the fraud had it not been for a disgruntled employee! Such a response highlights the importance of ethical conduct at all levels of a research team.

About this time the Good Clinical Practice (GCP) guidelines were published by the International Conference on Harmonization. This group established international, ethical scientific standards for designing, conducting, recording, and reporting trials that involve human subjects. By adhering to these standards the public could be assured that the rights, safety, well-being and confidentiality of trial participants are protected, consistent with the Declaration of Helsinki, and that clinical trial data are credible and accurate.

The birth of “informed consent”

A major focus of the Declaration of Helsinki, GCP guidelines, and the federal regulations is informed consent. Informed consent is a formal, voluntary process. It is not merely a form to be read quickly and signed. The elements of informed consent (Table 3) include the following: that the individual is consenting to participate in a research study, the purpose of said research, the likelihood of being assigned to one or another group if there is more than one group, the duration of the study, and the approximate number of participants to be studied. It also describes the procedures to be followed including the participants’ responsibilities, any aspects of the research study that are experimental, and the anticipated risks, benefits and alternatives. Informed consent outlines payment and any expenses for participation as well as compensation in case of injury, and the person to contact for general information or study-related injury. It makes clear that participation is voluntary and that one can withdraw at any time without penalty or loss of benefits. Potential subjects must be aware that access to research records is available to monitors, auditors and regulatory authorities, but that confidentiality must and will be maintained. New information about continued participation is promised and provided in a timely fashion and volunteers must be made aware when their participation can be terminated.

Even after decades of experience with the informed consent process, a number of issues continue to be discussed and debated. Some examples are how to provide information that is understandable across a broad spectrum of individuals from diverse educational, economic and race/ethnicity backgrounds; how to preserve privacy and maintain confidentiality of the research information; how to recruit research participants; and when and how much to compensate them for their involvement.

Table 3. Key Elements of Informed Consent

- Consenting to research

- Purpose of the research

- Likelihood of being assigned to one or another group

- Study duration

- Procedures to be followed and the ones that are experimental

- Participant responsibilities

- Anticipated risks and benefits

- Alternative(s) to participating in the research

- Compensation if injured

Conclusion

There is a great deal more that can be written about the responsible conduct of research involving human subjects, but the intent of this communication was to highlight key concepts and issues that continue to engage researchers, ethicists and others. Hopefully, this has been achieved. In summary, clinical research is essential to our ability to better understand disease and improve human health. Consequently, everyone involved in research with human subjects must do the research thoughtfully and as carefully and safely as possible.

References

- Code of Federal Regulations, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Available from: http:// www.hhs.gov/ohrp/humansubjects/guidance/45c fr46.html#46.102

- Emanuel, E.J., D. Wendler, and C. Grady, What makes clinical research ethical? JAMA, 2000. 283(20): p. 2701-11.

- Trials of War Criminals before the Nuremberg Military Tribunals under Control Council Law, The Library of Congress, No. 10, Vol. 2, pp. 181-2, Avail- able from: http://www.loc.gov/rr/frd/Military_Law/ pdf/ NT_war-criminals_Vol-II.pdf

- World Medical Association declaration of Helsinki. Recommendations guiding physicians in biomedical research involving human subjects. JAMA, 1997. 277(11): p. 925-6.

- The Belmont Report 1979, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Available from: http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/policy/belmont.html

- The Common Rule, US Department of Health and Hu- man Services, Available from: http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/ humansubjects/guidance/45cfr46.html

- http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/Guidances/ ucm073122.pdf

- Krugman, S., The Willowbrook hepatitis studies revisited: ethical aspects. Rev Infect Dis, 1986. 8(1): p. 157-62.

- U.S. Public Health Service Syphilis study at Tus- keegee, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/tuskegee/ timeline.htm

- Hagmann, M., Scientific misconduct. Cancer re- searcher sacked for alleged fraud. Science, 2000. 287(5460): p. 1901-2.

- Bezwoda, W.R., L. Seymour, and R.D. Dansey, High- dose chemotherapy with hematopoietic rescue as primary treatment for metastatic breast cancer: a randomized trial. J Clin Oncol, 1995. 13(10): p. 2483-9. Retraction in J Clin Oncol. 2001 Jun 1;19(11):2973.

- Eichenwald, K. and G. Kolata, A doctor’s drug studies turn into fraud. N Y Times Web, 1999: p. A1, A16.

About the Author

Lewis J. Smith, MD is Professor of Medicine, Director of the Center for Clinical Research in the Northwestern University Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute, and Associate Vice President for Research at Northwestern University. He chairs the Pulmonary Committee of the longitudinal Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study.