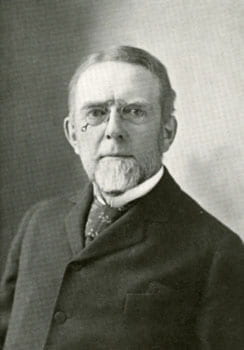

Daniel Bonbright

President ad interim

President ad interim

1900 – 1902

Born:

March 10, 1831

Youngstown, Pennsylvania

Died:

November 27, 1912

Daytona, Florida

Education: A.B., Yale (1850); A.M., Yale (1853); Hon. LL.D., Lawrence University (1873); Hon. LL.D., Northwestern (1908)

Biography

The man who became the eleventh president of Northwestern, Daniel Bonbright, was a young classics scholar not long out of Yale and recently done with a stint teaching in Georgia and Pennsylvania, when he was discovered by Northwestern’s trustees. They quickly saw his potential and offered him a position as professor of Latin Language and Literature in 1856. But Bonbright wanted to further burnish his academic credentials before settling in, so he countered with a proposition of his own: he would begin teaching at Northwestern only after two years of further study, among the elite scholars of Germany. Clearly, he was conscientious, self-confident, and serious about the role he intended to play in the academic world. In 1858, after attending the Universities of Berlin, Bonn, and Gottingen, and with some trepidation at the prospect of leaving the more refined precincts of Europe and the East Coast, he installed himself in Evanston. As it happened, he remained there for fifty-four years, a pillar of the university and the broader community.

It is difficult to think of anyone who embodied the University as wholeheartedly as Bonbright had come to do by the end of his career. As President Abram Winegardner Harris rightly said in eulogizing Bonbright upon his death on November 27, 1912, “Probably no man in all [the University’s] history has had a more dominant influence upon its spirit and methods.” In addition to his tenure as president, he was esteemed for shaping the early curriculum; for setting the university’s standards with what one commentator called “a fine Greek sense of proportion”; and for what used to be called the “moral formation” as a teacher. In keeping with his utter devotion to the University’s best interests, in 1890 he wed Alice D. Cummings, the daughter of former Northwestern president, Joseph Cummings.

As if that weren’t enough, Bonbright also had a hand in the conception of University Hall, establishing its overall design for the architect to translate into stone, and was responsible for the definitive version of the University Seal. He was instrumental in forming the University Library, acting as librarian for the fledgling university, while later, back in Germany for his health in 1869, he secured for Northwestern the coveted Schulze collection, which became a prized nucleus for the growing library. The list of his accomplishments goes on, both at Northwestern and beyond.

Born on March 10, 1831, in Youngstown, Pennsylvania, his first two years in higher education were spent at Dickinson College, and he transferred in 1848 to Yale, receiving his A.B. there in 1850 and his A.M. in 1853. After a stint teaching in Georgia and Pennsylvania, he returned to Yale in 1854 to enter the Theological Seminary and act as Tutor before encountering the trustees of Northwestern two years later. In the course of his many years at the university he was the Professor of Latin Language and Literature (1856-1888), the University Librarian (1855-1865) the John Evans Professor of Latin Language and Literature (1888-1912), the Dean of the College of Literature and Science (1873-1878), Dean of the College of Liberal Arts (1878-1902), Dean Emeritus (1902-1912), as well as the President ad interim in 1900-1902. Also at Northwestern, he was granted an honorary LL.D. in 1908. While beyond the university, he was a founder of the Evanston Philosophical Society (1866), and received another LL.D., from Lawrence University in 1873.

When President Henry Wade Rogers left Northwestern in 1900 in a turbulent separation, it was natural for the trustees to turn to the reassuring sense of continuity that Daniel Bonbright would provide as acting president, even as Bonbright had worked harmoniously as dean with Rogers – although it was understood that Bonbright had no ambitions for a permanent appointment, given his aversion to administrative routine and his commitment to the classroom (though not to academic publishing, for quite designedly, he never published anything during his long career). He accepted the position reluctantly, though two other times in the University’s history he did decline the same role.

Bonbright remained as president for nineteen months, concentrating on the Evanston campus while leaving the deans in Chicago free to manage their schools’ affairs according to their best lights. He was instrumental, however, in the significant purchase of the Tremont Hotel Building at the corner of Lake and Dearborn in Chicago. It was remodeled and re-christened the Northwestern University Building, and housed the schools of Law, Pharmacy, and Dentistry. This was an important step in consolidating and strengthening the academic role of the urban faculties.

Back in Evanston, Bonbright was preoccupied with finding ways to bolster enrollment so as to ensure the momentum of predecessor Rogers’ expansion. He persuaded the trustees to institute one-year tuition scholarships for Illinois’s most promising high school students and, concomitantly, recommended a veritable publicity campaign, with representatives in the field informing students and parents of the University’s merits. Furthermore, Northwestern acquired a financial interest in two preparatory schools on the verge of bankruptcy, Grand Prairie Seminary at Onarga and the Elgin Academy, as a sort of farm system for the university. And Bonbright reinstituted the previously discontinued curriculum in engineering.

On one issue Bonbright was at odds with the trustees. His prudential—not to say conservative—bent was very much in evidence in his attitude toward the growing percentage of women on campus, which he favored halting, despite his concern for expansion, by limiting the current coeducational component to the existing dormitories. Under Rogers this component had increased from 36% to 50% of the student body, and Bonbright was known to be wary of Northwestern acquiring a “feminine image;” indeed, there is evidence that the University was acquiring a reputation of being a “girls’ school.†It isn’t farfetched to wonder whether this image was partly at the root of Northwestern’s less than stellar athletic accomplishment in the first several decades of the 20th century. In any case, Bonbright recommended that the trustees discourage further emphasis on coeducation; in the event, the trustees chose not to heed him and in fact, authorized the construction, with Bonbright’s in the end ready acquiescence, of Chapin Hall as a new women’s residence. Meanwhile Bonbright lobbied for a central dining hall for men as a further counterweight.

When in March, 1902, the University retained Edmund Janes James to succeed him, Bonbright returned gratefully and with relief to the classroom, where he continued to flourish for another decade. When James left Northwestern in 1904 to assume the presidency of the University of Illinois, the trustees again turned to Bonbright, but this time he declined, preferring to devote his remaining years to his students. The last word on Bonbright must be left to University historian Arthur E. Wilde in his History of Northwestern University 1855-1905: “His nobility of character, his familiarity with the history and traditions of the institution, and the maturity of his judgment gave him in peculiar degree the confidence of the trustees.”

A memorial plaque presented to the University as a gift from the Class of 1913 and commemorating the life of Daniel Bonbright hangs today, no doubt comfortably, in the lobby of University Hall.