By Lindsey Williams

The Object in Question

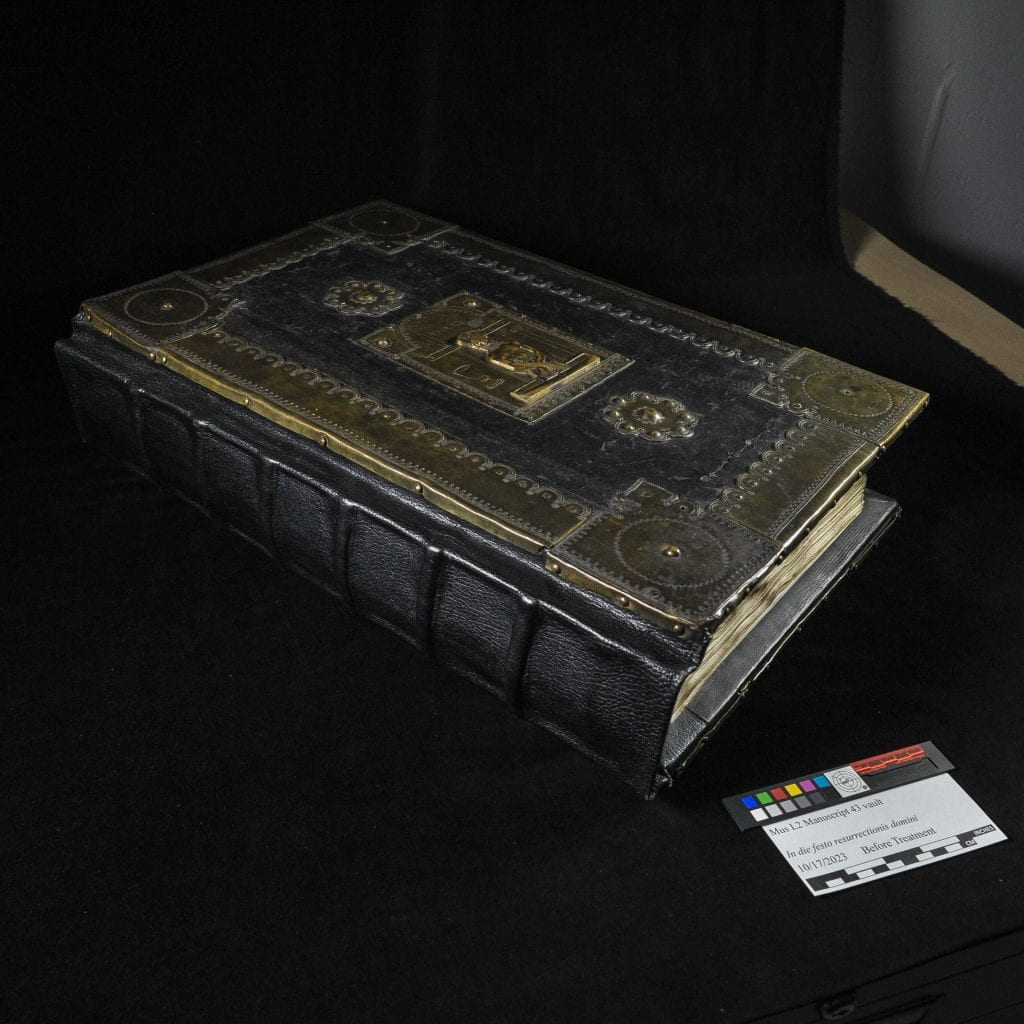

In Die Festo Resurrectionis Domini is a 15th century gradual, or choir book, used during the time of Easter through Pentecost and contains choral songs for a Roman Catholic Mass. The gradual is comprised of 270 parchment leaves measuring 49cm x 32cm each: approximately 135 skins of goat making up the textblock. The covers are constructed of wooden boards covered with leather and framed with brass edging. A hefty volume, it is about 5” thick including its cover boards with impressive brass decorative elements featuring the resurrection of Christ and the Madonna and Child. While much of the volume is original, it was rebound by local Chicago bookbinders, William Anthony and Elizabeth Kner, in the 1970s using its original boards.[i]

Assessing the Situation

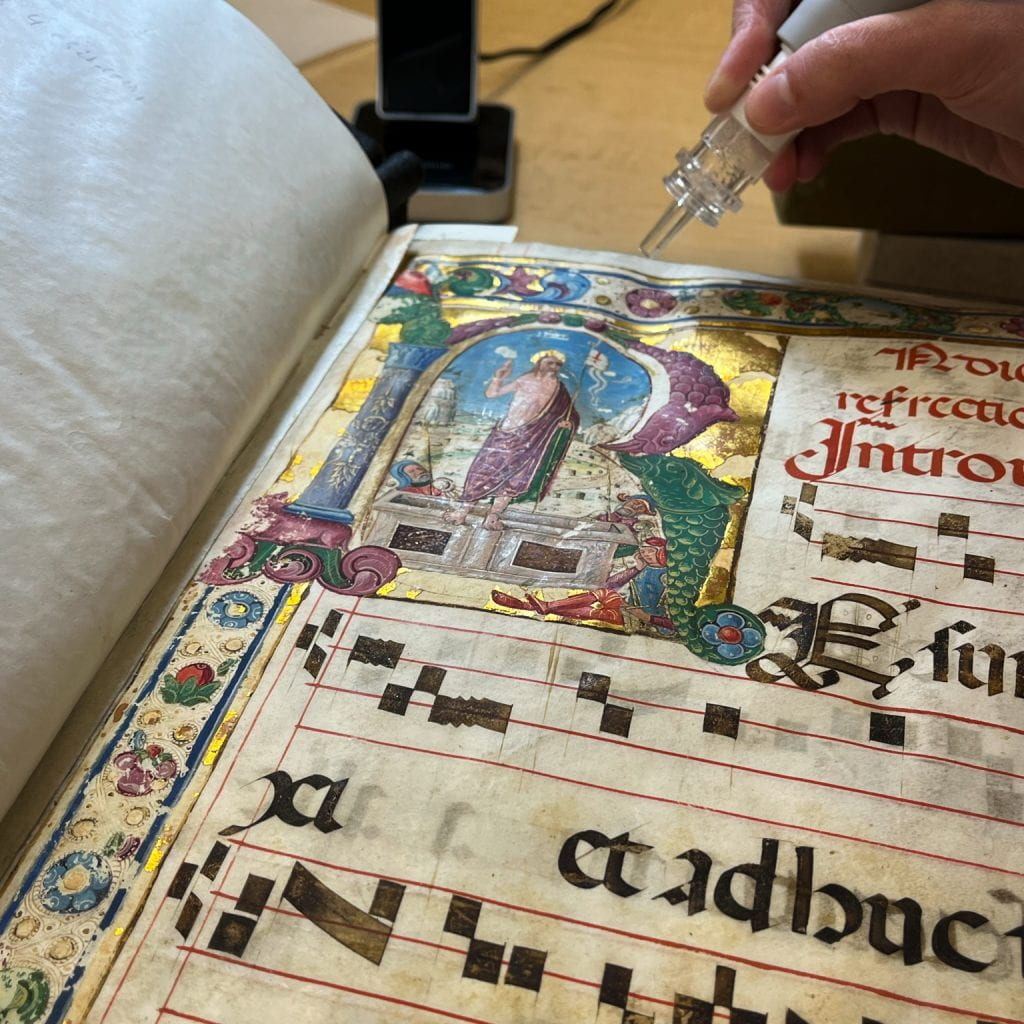

Prior to exhibition, staff in the conservation lab conduct a condition assessment for each item to ensure it is structurally stable and then complete any necessary treatments. This volume was one of many to arrive for the exhibit coinciding with the 2024 Vagantes Medieval Conference. During this assessment, pigment fragments were found in the gutters of the pages, and the text and music notation appeared to be deteriorating, creating losses throughout (IMAGE 2). It was determined that due to its size, it could not be exhibited open, but treatment of some of the illuminations and text was still necessary.

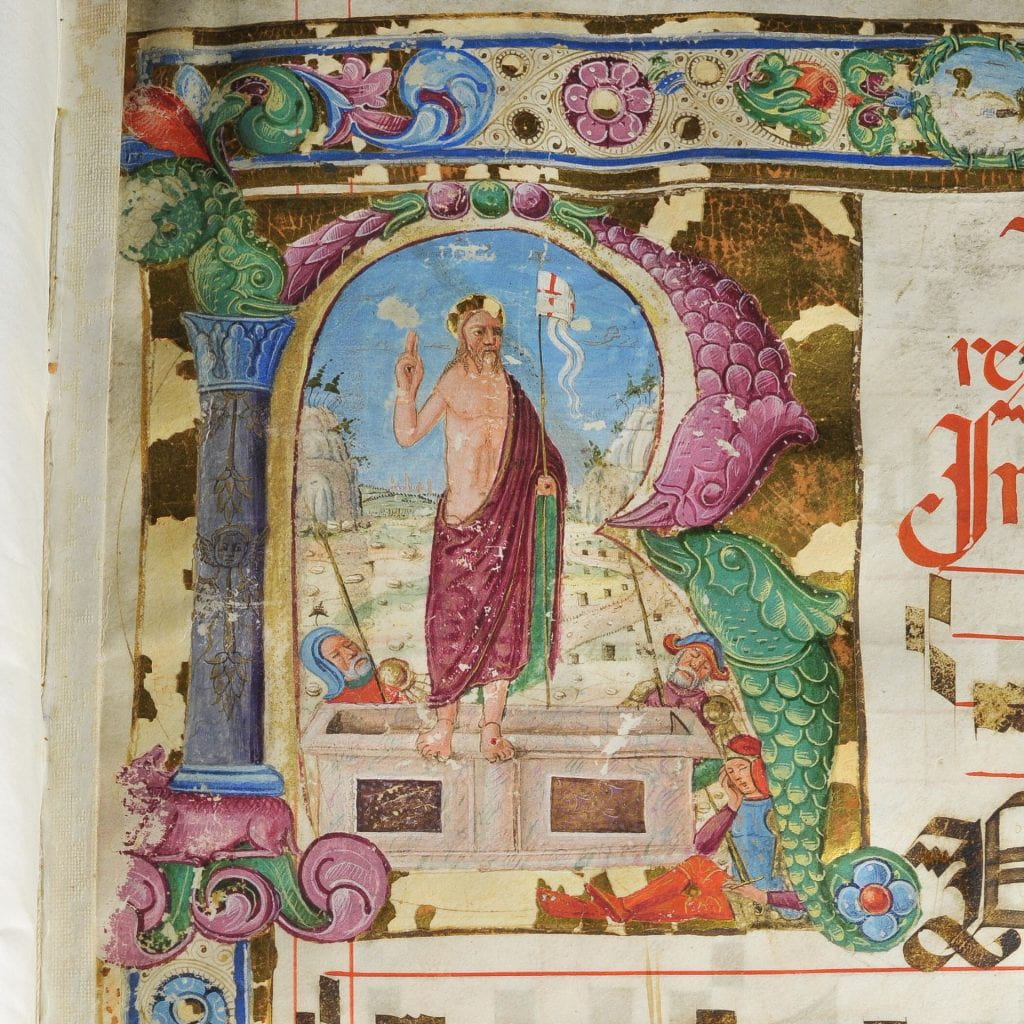

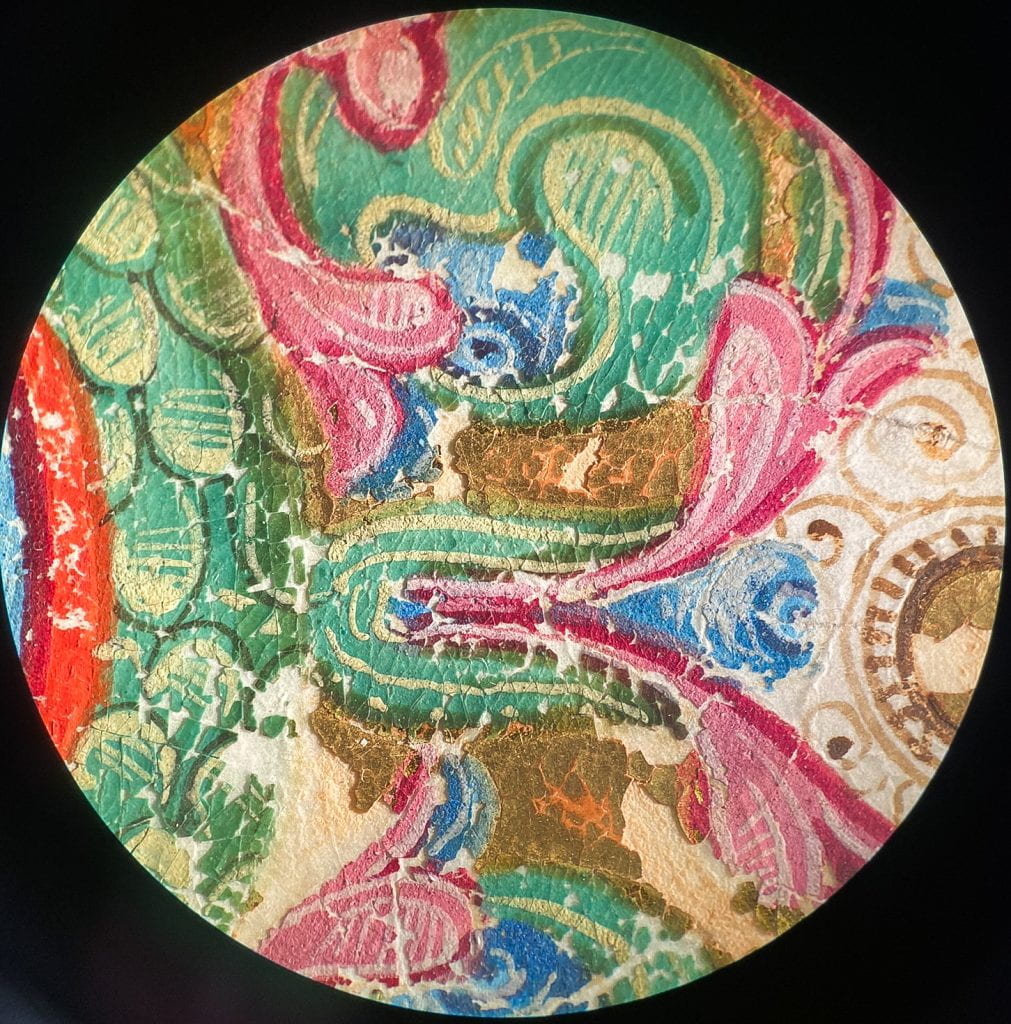

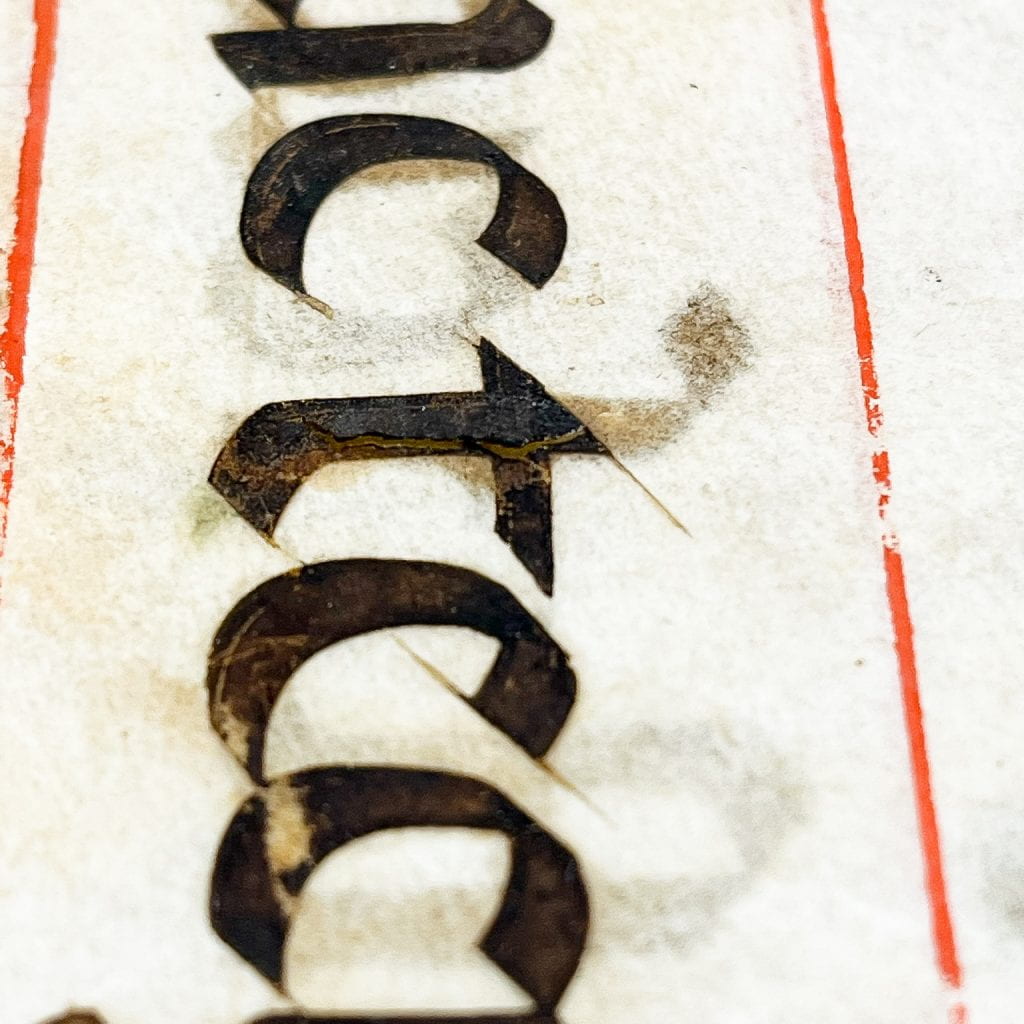

The parchment pages are heavily warped due to age, handling, and their reaction to humidity and temperature fluctuations. (IMAGE 3) The lower corner of each page has darkened and softened alluding to its use. Parchment, being the skin of an animal, doesn’t like to be flat and often will curl or warp, as if to return to its pre-stretched state, creating an uneven surface. Gilded and painted areas on the page don’t have the same flexibility as the parchment resulting in flaking, cracking, and complete detachment from the page. (IMAGE 4) In the gilded areas, gold leaf sits on a layer of toned bole (underlayer); the thick layer is inflexible causing some areas to lift, become detached, or lost completely.[ii] We could see that this manuscript had a red-toned bole from the cracks in the gilded areas. In areas where there was loss of either gilding or paint layers, a faint brown ink under-drawing could be seen. (IMAGE 5)

The text and music notation, written in iron gall ink, were also an area of concern. Due to the acidic nature of this ink, some of the notation and lyrics were corroding. This occurs when migrating iron ions in the ink effectively burn their way through the parchment or paper. (IMAGE 6) To mitigate further damage, it was determined that media consolidation should be done, which involves the use of adhesives to secure detaching or fragile areas to the support. We prioritized treatment of the illuminations, since they are unique to this volume, and selective areas of text.

Going Under

Media consolidation is a typical conservation treatment done on illuminated manuscripts. The timeline for the treatment and the size of the volume necessitated that this be a lab-wide effort, and we needed a system to ensure our work was successfully tracked. The protocols from Harvard’s Weismann Preservation Center proved to be the perfect model for us to use, with some adaptations.

We chose to use Isinglass as our consolidant. Isinglass is “a protein glue, which is extracted from the swim bladder of sturgeon…[i]t is still frequently used in paintings conservation because of good tack, transparency, elasticity, hygroscopicity, continuous solubility and low overall tension….”[iii] To address both the illuminations and the ink, the Lab used two techniques to apply the consolidant: brush-applied and mist-applied using a medical nebulizer.

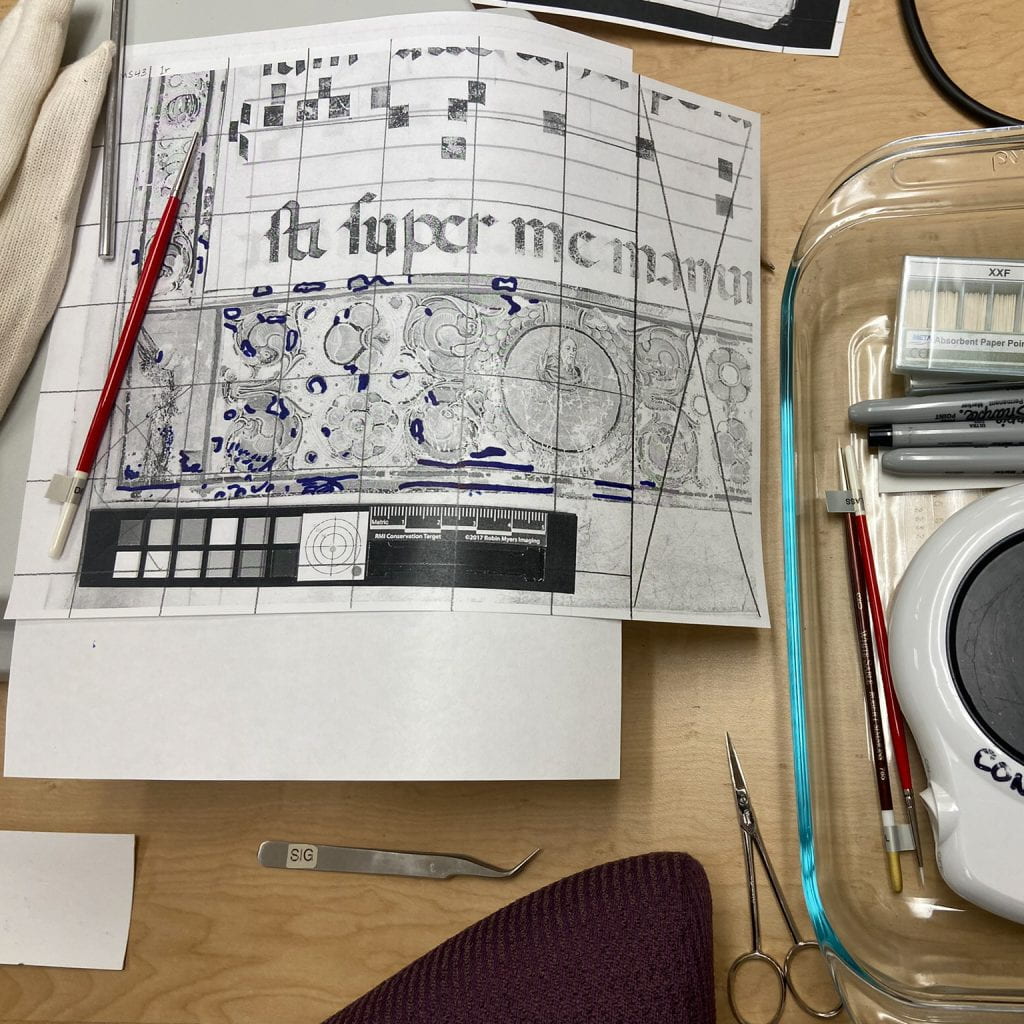

Stephanie Gowler, the Book and Paper Conservator, as the project manager, prepared the photographic documentation for each page to be consolidated. By drawing grids on the documentation pages, we tracked areas of damage and our consolidation process (IMAGE 7). This was especially important for our brush-applied technique which involved discerningly placing droplets of isinglass while looking through a microscope.

Some of the pigments surprised us by turning a different shade when consolidated but reverted to their original tone once dry. One pigment in particular, a smooth purple-red found on top of gilded areas, appeared to readily-soluble in isinglass (IMAGE 8) and required a delicate touch. Another color that required intense delicacy was the light green pigment that appeared glossy and cracked like an enamel surface, which frequently flaked off in miniscule pieces when touched or stuck to our brushes. (IMAGE 9)

The first page was especially fragile and needed significant consolidation. It was decided that mist-application would be a more expedient and viable treatment for this heavily illuminated page. Lea Faoro, Project Conservator, set up the medical nebulizer and determined the concentration of isinglass that could be misted without losing its viability as a consolidant. (IMAGE 10) This process involved a slow, steady hand guiding the nebulizer across the page, allowing the mist to settle on top of the entire page and creating a slight isinglass film under which all the pigments and ink would be secured. (IMAGE 11) We treated this volume in January, when the ambient relative humidity was low, and as we worked, we saw the curling fore-edge of the page relax and lower, like it had just released a breath. It was the introduction of moisture from the nebulizer that resulted in this reaction and showcased immediately parchment’s sensitivity to fluctuations in humidity.

After each session, pages were left to dry for at least 30 minutes. We found that overall adhesion was surprisingly immediate, but we checked our consolidated areas before moving on as some areas required a second go-round with the brush.

The biggest factors that impacted our work were the weight/size of the volume, unpredictable reaction of the pigments to the consolidant, and the atmospheric relative humidity due to the season. We always needed two people to maneuver the volume, and we tried to move it infrequently. After prioritizing the first page and some of the other illuminations, we discontinued further treatment because of the low humidity in the conservation lab. We didn’t want to risk causing further media issues while attempting to remedy existing ones. After the treatment, the volume was returned to its storage location in Deering Library, which is climate controlled to be 60°F and 40% RH, before being installed in the exhibition.

You can check out the exhibition featuring this manuscript and its companions of medieval music books and manuscript fragments in the Deering Library’s lobby exhibition space from February 8th through June 10th. While you will only be able to see the back cover with its brass relief in the exhibition, this blog gives you a peek inside. Visit the McCormick Library of Special Collections and University Archives after the exhibition to see more for yourself.

Photographs by conservation staff: Stephanie Gowler, Jess Ortegon, Lindsey Williams, and Lea Faoro.

[i] https://surface.syr.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1043&context=sul

[ii] https://uregina.ca/lucasa/Raised%20Gesso%20Gilding%20Techniques.pdf

[iii] https://kipdf.com/technical-paper-11-scottish-renaissance-interiors-facings-and-adhesives-for-size_5ab1057a1723dd329c637031.html