By Paul Feller-Simmons ’25 PhD and Phoenix Gonzalez ’26 PhD

This blog post is adapted from the exhibition Scripts and Performances: Uncharted Medieval Manuscripts at Northwestern University, on view in Deering Library until June 10. The exhibit was curated by Paul Feller-Simmons (’25 PhD) and Phoenix Gonzalez (’26 PhD) with Lauren Cole (’27 PhD) and Ben Weil (’26 PhD). This exhibit serves as a prelude to the 23rd Annual Vagantes Conference on Medieval Studies, held at Northwestern, March 21–23. As this conference showcases graduate work at the nexus of the humanities, it also explores the theme of “performance.” In this spirit, the exhibit converges on a selection of European music manuscripts, both complete volumes and fragmentary remnants, drawn from Northwestern’s Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections and University Archives and the Music Library. Photography by Jasmine Shah, Kimberly Kwan, and Liz Cassidy.

A sumptuous compendium of processional songs gathered in the 1500s for nuns in Naples under the auspices of the noble Carafa family; manuscript fragments with sacred songs rendered obsolete by religious reform, torn to be used as binding material for later codices; a choir book from Florence in consistent use from the 1200s until the 1850s displaying the wear and tear of centuries of daily devotional practice. These are just some of the early music manuscripts preserved in Northwestern University Libraries, and they represent differing manifestations of music and musical performance–understudied, uncatalogued, and often ignored by scholars. We invite you to approach your librarians to learn more about such collections.

Presented here are manuscripts and manuscript fragments that bear witness to differing ways of reading, writing, and performing music, as well as religiosity, sociability, power, and identity in premodern Europe. As such, these documents lie at the root of what music means today. The collections display a variety of visual techniques for recording sounds that convey the musical parameters of Gregorian chant, a ubiquitous form of Christian sacred music in the European Middle Ages. Also known as “plainchant,” this genre was monophonic — sung with a single melodic line. Amid the quiet of preindustrial Europe, plainchant rang out in monasteries frequented by pilgrims, in lavish cathedrals, and in parish churches, developing into a dynamic tradition that echoes into modernity.

The survival of plainchant depended on the ability of those who sang it, largely through patterns of oral transmission and highly-localized performance practices. Notating music was not the norm in the Middle Ages. Although we might imagine music literacy today as consisting of straightforward and universal processes, this collection of manuscripts and manuscript fragments attests to the great variety of historical techniques used to notate sacred music. From the early forms of Western technologies for inscribing music— graphic symbols known as neumes—to the later-standardized “‘black square notation,” these manuscripts collectively form a visual symphony, illuminating various stages in the acoustic performance of medieval religiosity.

Notating music was an expensive and time-consuming endeavor. Manuscripts were meticulously assembled from treated animal skin, known as vellum or parchment, usually by teams or artisans, requiring substantial time and resources. The tomes were ornately bound, ruled with precision, provided with text, music, and rubrics, and adorned with intricate decorations, showcasing the dedication and craftsmanship of its creators. We encourage you to think about how the manufacture of each manuscript necessitates consideration of factors such as structures of power and authority. The very act of recording music implies negotiations of sociability and attempts to unify and define the acoustic communities that produced these documents. Each manuscript, whether written in and for specific religious communities, regions of Europe, ecclesiastical institutions, or individual patrons, embodies distinct forms of performance: of self, power, identity, and everyday life.

As you traverse this visual (and auditory) journey into the past, may you uncover the nuanced performances encapsulated within these meticulously preserved documents.

Early Fragments

Here we showcase uncatalogued manuscript fragments and membra disjecta — loose leaves belonging to larger volumes — offering a glimpse into the early forms of music notation. These artifacts document a progressive, albeit not linear, attempt to codify various parameters of sound. The sequence observed here is intricately tied to efforts aimed at unifying the Christian liturgy, particularly the chants performed during religious ceremonies, in the wake of the rise of the Carolingian Empire circa 800 CE.

Before this pivotal period, the dissemination of Christianity had given rise to diverse local rites across different regions of Europe. The concerted efforts of influential European centers and the papacy initiated a transformative process. Singers, accompanied by newly crafted music from Rome, were dispatched to various liturgical centers throughout Central Europe. This orchestrated exchange, akin to a slow circulatory system, facilitated the emergence of a new form of chant — the Franco-Roman or Gregorian chant.

As potentates made sure to disseminate this new musical practice, many local traditions faced the risk of endangerment by the twelfth century. The case invites contemplation on the performance of religious and political power during this transformative period, as well as the role of music notation in shaping the harmonious fabric of medieval Christian liturgy.

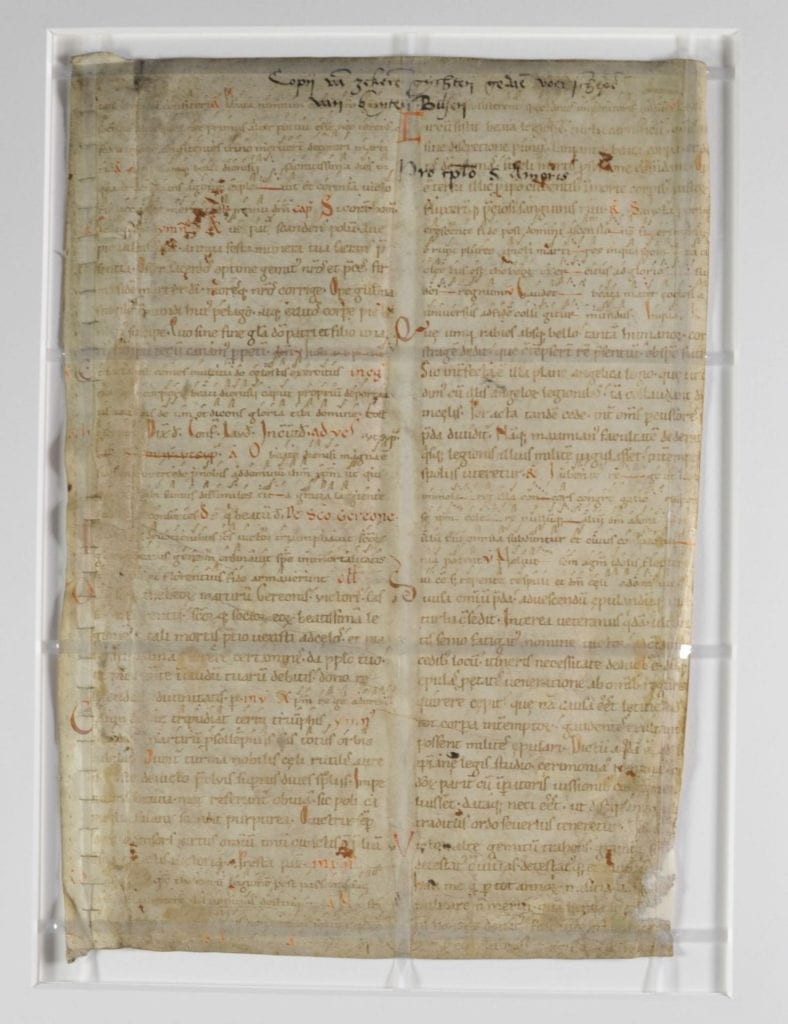

Fragment 1 possibly represents the earliest trace of notated music at Northwestern University. The script employed in this manuscript aligns with what we identify as “Carolingian minuscule,” a style that emerged after the year 800, coinciding with the ascendancy of the Carolingian Empire in Central Europe. Within the fragment, a portion of the text remains legible, including “[Sicut erat] in principio et nunc et [semper],” an excerpt from the Latin doxology – a brief hymn praising God. Overlaying these words are lines of distinctive shapes, marking the earliest form of Western musical notation known as adiastematic neumes. Notably, these neumes, devoid of rhythmic cues or precise pitches, served as mnemonic devices. Their primary function was to aid in the recollection of plainchant learned through oral tradition. The neumes showcased in this fragment thus exemplify a unique form of hierarchical sociability crucial for the transmission of the musical repertory. The script and the style of musical notation suggest that this fragment predates the eleventh century.

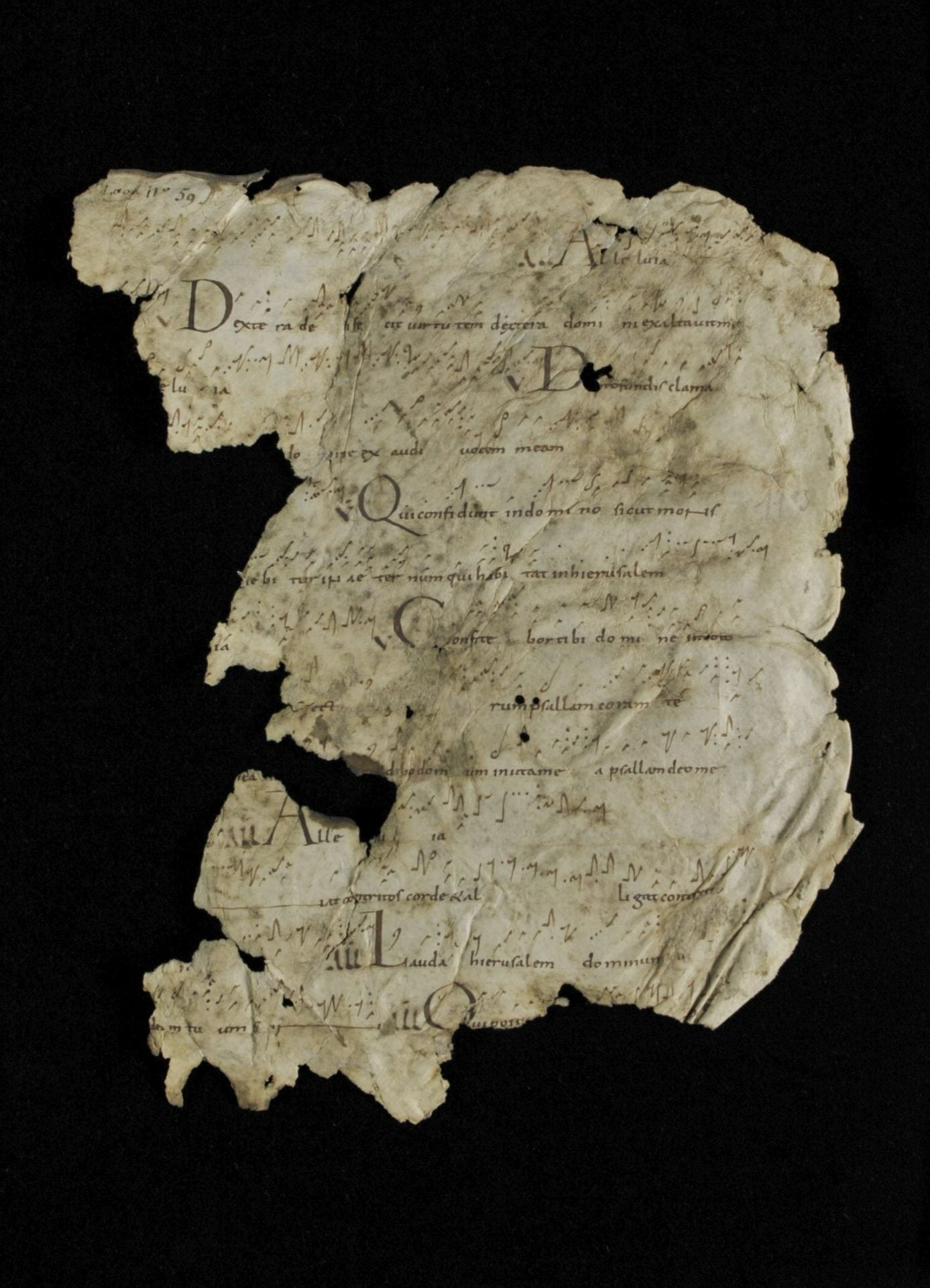

Fragment 2 is a single, weathered leaf, bearing the inscription “Laon IVo 59” on the upper left corner – a poignant reminder of its origins in the medieval manuscript collection of Laon, a northern French cathedral town renowned for its extensive holdings of plainchant books dating back to the twelfth century. Despite the evident wear and tear, this membrum disjectum reveals several discernible Latin sentences, hinting at a compilation of “Alleluias.” These liturgical chants, a blend of verses from scripture and the exultant refrain “Alleluia,” traditionally found their place before the proclamation of the Gospel during religious ceremonies. Notably, these chants are characterized by the jubilus, a protracted melodic line, or melisma, on the word ‘Alleluia’ symbolizing rejoicing. The adiastematic notation employed in this fragment, while not divulging specific pitch levels, marks a noteworthy difference from fragment 1. A visible spatial deployment and breakdown of neumes suggest an effort towards a more refined definition of the melodic line.

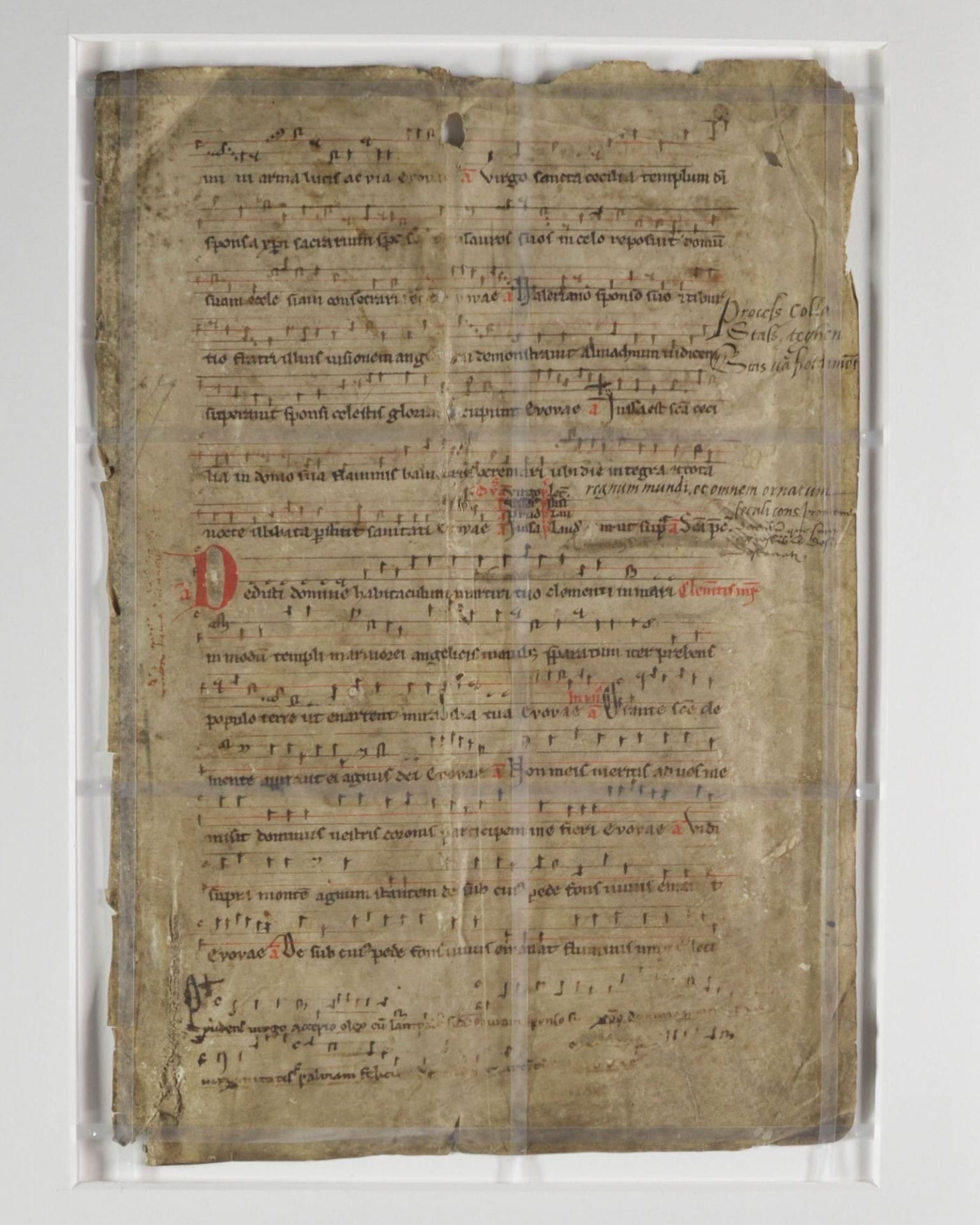

Uncatalogued fragment 3, c. 1100. Photo by Kimberly Kwan.

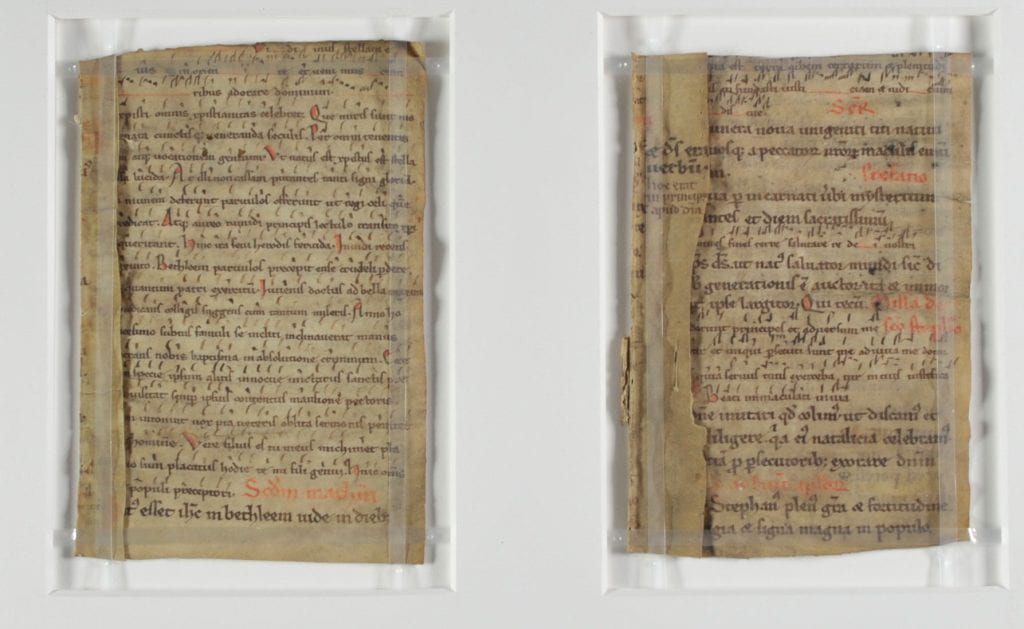

Fragment 3 is a testament to the multifaceted nature of medieval liturgical music books. It represents a common trend in that era, when the majority of these manuscripts mixed textual and musical content. Some of the musical sections begin with a red A — a rubric — indicating that the song is an antiphon, a sentence sung before or after a psalm or canticle. A distinctive characteristic is the presence of adiastematic neumes, possibly added later, serving as a mnemonic aid to recall local melodies. This practice sheds light on the nonlinear progression of notational practices, illustrating how different regions of Europe embraced diverse and similar notational strategies at varying points in time. The neumes showcased here bear a striking resemblance to those found in southern Germany and Switzerland, suggesting a regional coherence in notational conventions. However, the writing on top, executed in a notably different script — is seemingly Gothic and thus later. Remarkably, this script is not in Latin but appears to be a form of early Dutch or Flemish, introducing a layer of linguistic and regional diversity.

Uncatalogued fragment 4, c. 1100

These two leaves offer another typical example of the convergence of text and chant in medieval manuscripts. The texts in red, or rubrics, indicate the different sections, such as the praefatio, or the liturgical prayer that serves as an introduction to the Eucharistic Prayer or canon of the Mass. This manuscript bears a distinctive notational style, a stark departure from fragment 3. While the neumes here are adiastematic, not fixing a specific pitch, they exhibit a striking variation as they tend to break down into single sounds and mostly exhibit vertical strikes termed virgae and dots known as puncta. Virgae and puncta are believed to represent relatively higher and lower sounds, respectively, providing a nuanced layer to the melodic interpretation. The lines, characterized by their notable thickness, add another dimension to the visual aesthetics, resonating with scripts present in exemplars from central Germany.

Uncatalogued fragment 5, c. 1100. Photo by Kimberly Kwan.

Fragment 5, a twelfth-century Italian membrum disjectum, hails from an antiphonary, a liturgical manuscript dedicated to the Liturgy of the Hours. Throughout the Middle Ages, the Liturgy of the Hours played a central role in organizing daily prayers, dividing the day into distinct intervals for devotion. This leaf encompasses music for matins, lauds, and vespers, aligning with evening and nocturnal hours.

Observe the neumes gracefully positioned atop the Latin texts. These early musical notations, precursors to modern musical symbols, are here accompanied by one or two colored lines intersecting them. These horizontal lines, a recent innovation around this period, pioneering attempts at establishing pitch levels, laid the foundation for what would later evolve into the pentagram or staff. A noteworthy aspect on the left side of the folio is the presence of small letters, c or f, at the beginning of each colored line. These letters mark the pitches C and F, considered pivotal for identifying chants due to their association with half-steps below (B and E, respectively). This ingenious system ultimately transformed into the clefs familiar in contemporary musical notation.

The deterioration pattern of this manuscript indicates that it was used as a pastedown to bolster the binding of a later volume. Manuscripts were expensive artifacts and were not easily disposed of. When a manuscript was no longer useful for some reason, they were often recycled in different ways. But, the very act of recycling a manuscript that would be used for singing daily prayers invites us to think about the performance of religiosity and power as chant manuscripts would often become obsolete when there were reforms made on the liturgical order.

Uncatalogued Notated Fragments, c. 1100-1200

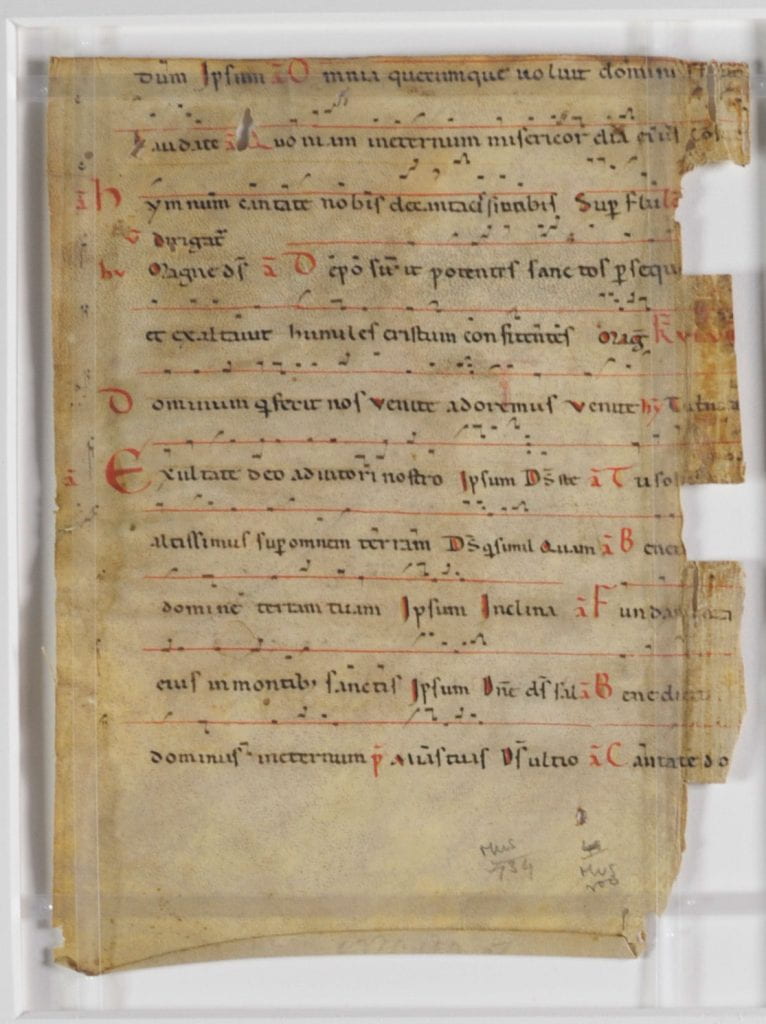

This selection of uncatalogued musical manuscripts trace the non-linear journey toward the regularization of musical notation in Central Europe. These artifacts provide an insight into the early attempts to further systematize the representation of music.

These manuscripts depict the use of neumes, symbols indicating different musical gestures over the syllables of a text. As in the fragments in this case, medieval scribes developed diastematic notation, a system that conveyed pitch levels through the combination of neumes and lines.

Despite these changes, it is noteworthy that the notation in these manuscripts is selective regarding which sonic features it determines. It omits, for example, details on rhythm, dynamics (volume), and timbre. This serves as a reminder that notation is a technology that only reflects the parameters necessary to aid memory.

Toward the end of the twelfth century, a development emerged in the form of tetragrams – four horizontal lines akin to a staff. This marked a significant departure from earlier forms of notation that only included one or two colored lines to underline the pitches C and F. Despite the introduction of tetragrams, the manuscripts retained the initial letters c and f at the beginning, sometimes simultaneously, symbolizing the pitches C and F. Tetragrams are still traditionally utilized in publications of plainchant such as the Liber Usualis.

The above manuscripts highlight the standardization of neume shapes into two distinct styles. The first style, called square notation, features squared neumes with occasional joint lines. The second style, characterized by elongated Gothic squared lines, is known as Hufnagel notation for its resemblance to the nails used to secure horseshoes (Hufnägel in German). It was predominant in Germany, persisting until the sixteenth century. From this point onward, the notation of plainchant is generally consistent in differentiating between single neumes for single sounds and ligatures — graphs groupings neumes — whenever more than one sound is to be sung on a single syllable.

Bound Manuscripts

Mss 1501 is a meticulously crafted processional originating from Northern Italy. This small and portable manuscript serves the liturgical processions, compiling essential Latin texts and chants. Despite its modest dimensions and limp binding, the manuscript’s Gothic bookhand, square notation on a tetragram for the music, and ornate pen-work initials attest to the professional craftsmanship invested in its creation.

The text within is limited to processions for the Purification of the Virgin (Candlemas) and Palm Sunday, aligning with the customary brevity of Franciscan Processionals. The book seems to have been manufactured for and probably by members of the Order of Friars Minor. An intriguing aspect is the inclusion of various forms of Requiem and burial services, encompassing ceremonies for friars, the laity, and children — a departure from typical Processionals. Additionally, Mss 1501 incorporates Gospel readings from the Palm Sunday and Good Friday masses, complete with notated music. This blend of liturgical elements within the manuscript provides valuable insights into the performance of devotion within late medieval religious orders.

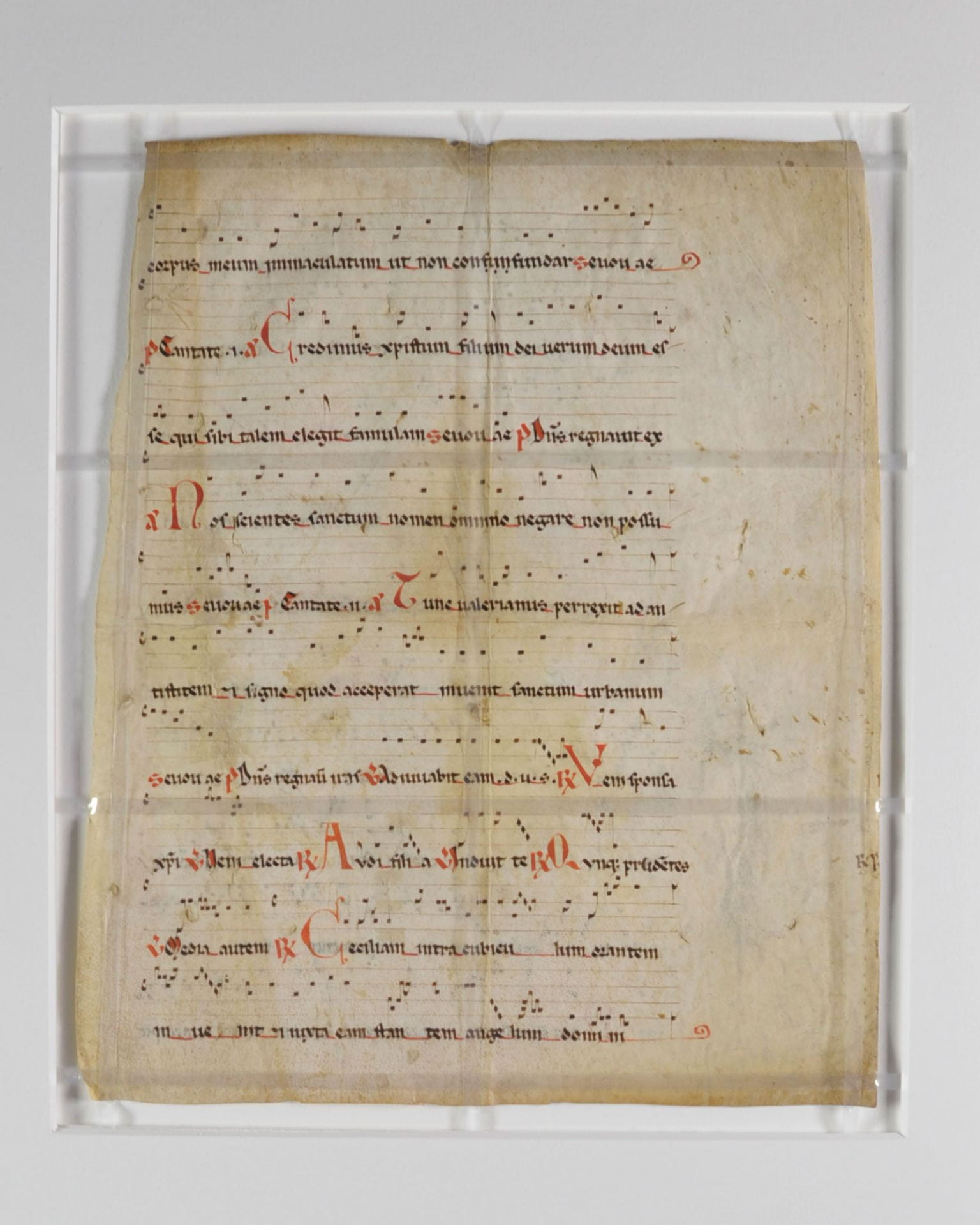

Mss 408 is a remarkable service book meticulously inscribed on vellum. This volume, a Sequentiarium, compiles sequences—chants integral to the liturgical celebration of the Eucharist, specifically preceding the proclamation of the Gospel. Sequences are often dedicated to saints and festivities that were important for a given region or institution. After the eleventh century, sequences adopted a structural format characterized by couplets — successive lines with rhyming and metric consistency. The Council of Trent’s reforms led to the abolition of most sequences by 1563.

The local nature of sequences allow for a tentative dating and localization of Mss 408. The inclusion of St. Thomas Aquinas’s “Lauda Sion” (c. 1264), coupled with rubrics and other sequences — such as “Sanctissim[a]e Virginis” — suggest that the manuscript was crafted for a nuns’ convent affiliated with the Order of Preachers (Dominicans), likely situated in Germany.

The musical notation in Mss 408 is a remarkable feature. The elongation of neumes in square notation, alongside unconventional ligature and clef forms, adds to the manuscript’s uniqueness. The volume’s existing binding, likely from the nineteenth century, reflects subsequent interventions in the manuscript’s history. This layered history contributes to the manuscript’s richness as both a cultural artifact and a testament to the differing practices surrounding the medieval recording of liturgical music.

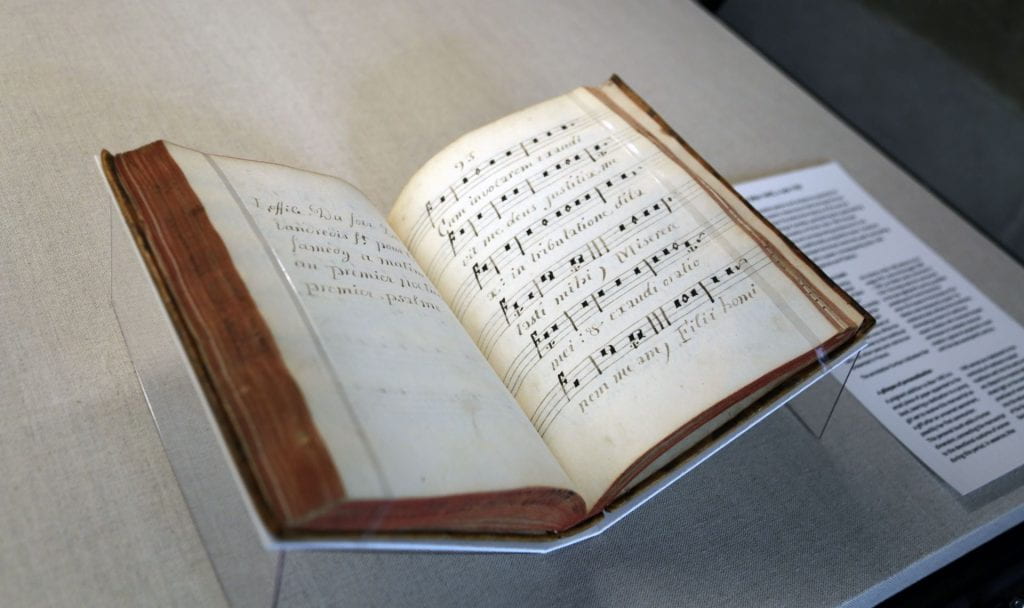

Mss 1462 primarily compiles psalms and antiphons essential for the Tenebrae service, a solemn observance held during the three days preceding Easter Day. The distinctive feature of the service is the gradual extinguishing of candles, symbolizing the approaching darkness before the resurrection of Christ. Mss 1462 focuses specifically on the psalms and corresponding antiphons for the canonical hour of matins, traditionally sung before dawn. Tenebrae matins were historically divided into three nocturnes, each concluding with an antiphon paired with a psalm. Consequently, Mss 1462 contains a total of 27 antiphons and Psalms.

A crucial annotation on the binding reveals that Mss 1462 was crafted for the Society of the Sisters of Saint Ursula, a religious congregation founded in 1606 in France. This society distinguished itself by offering free education to girls, following Jesuit models, without the requirement of becoming cloistered nuns. While the plainchant adheres to the traditional Latin, all other texts and rubrics are presented in French. The annotation further indicates that the chants in Mss 1462 adhere to the usage of St. Louis de Gonzaga (1568 – 1591), an Italian Jesuit canonized in 1726. This helps date the manuscript to the late eighteenth century, possibly predating the French Revolution when the houses of the Society of the Sisters were temporarily closed. The notational style reflects this timeframe, showcasing a blend of traditional square notation with rhomboid shapes reminiscent of outdated mensural notation, typical of polyphonic music until the late seventeenth century.

A poignant addition to Mss 1462 is a small piece of paper appended to the book, bearing a dedication to a young girl set to receive this manuscript as a gift after an unnamed sacrament, possibly her first communion. This personal touch adds a human dimension, connecting the manuscript to the devotional customs of women during this period. In essence, Mss 1462 serves as a testament to the continuity of medieval musical traditions well into the early modern era. Beyond its musical significance, it sheds light on the social and devotional practices of women, offering a glimpse into the education within the context of the Society of the Sisters of Saint Ursula.

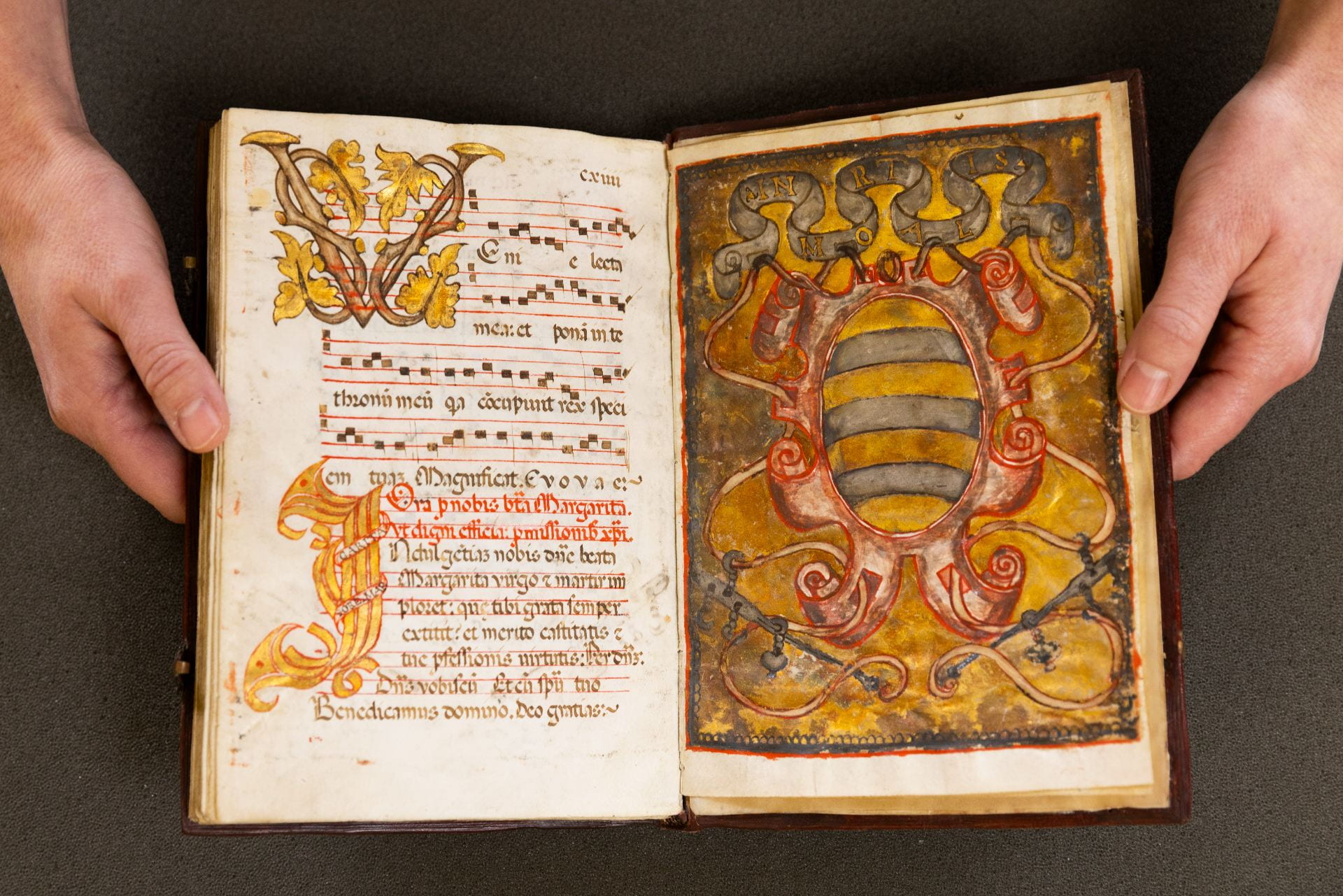

One of the true gems of the medieval collections at Northwestern, Mss 1513 is a distinctive Ordinal-Processional, a liturgical compendium providing directives, texts, and chants for Dominican observances, processions, and rituals. The book also includes texts and music for the liturgy for death and burial. Crafted in Latin and Italian, this manuscript is a visual masterpiece, adorned with opulent illuminations and musical notation. The colophon at the end of the volume unequivocally marks its completion on March 24, 1556. Despite its late date, Mss 1513 adheres to medieval models, featuring black square notation on a tetragram, red rubrics, and rounded Gothic bookhand — a nod to the enduring legacy of medieval traditions. The accompanying calendar, customary in many medieval books, highlights Dominican saints like Vincent Ferrer and Catherine of Siena. Additionally, saints associated with Naples, such as St. Severus and St. Euphebius, further help locate the manuscript. The Renaissance influence is evident in the gilded ornaments, reflecting a preference for delicate filigrees.

Notably, the Latin texts within the Ordinal-Processional use feminine language, referencing the “cantrix” or chantress, indicating its intended audience — Dominican nuns. Strong evidence suggests that Mss 1513 may have been crafted for a member of the noble Carafa family, possibly residing at the Neapolitan convent of Santa Maria della Sapienza.

The Carafa family, a prominent aristocratic lineage, held significant influence over Naples since the twelfth century. At the time of the manuscript’s creation, Pope Paul IV (born Gian Pietro Carafa) ruled the Papal States. Earlier, when he was a bishop, Paul IV had transformed the convent of Santa Maria della Sapienza into a Dominican order, appointing his sibling, Maria Carafa, as prioress until 1552. Numerous family members continued their association with the Sapienza throughout the sixteenth century, which suggests that this book was prepared for one of them.

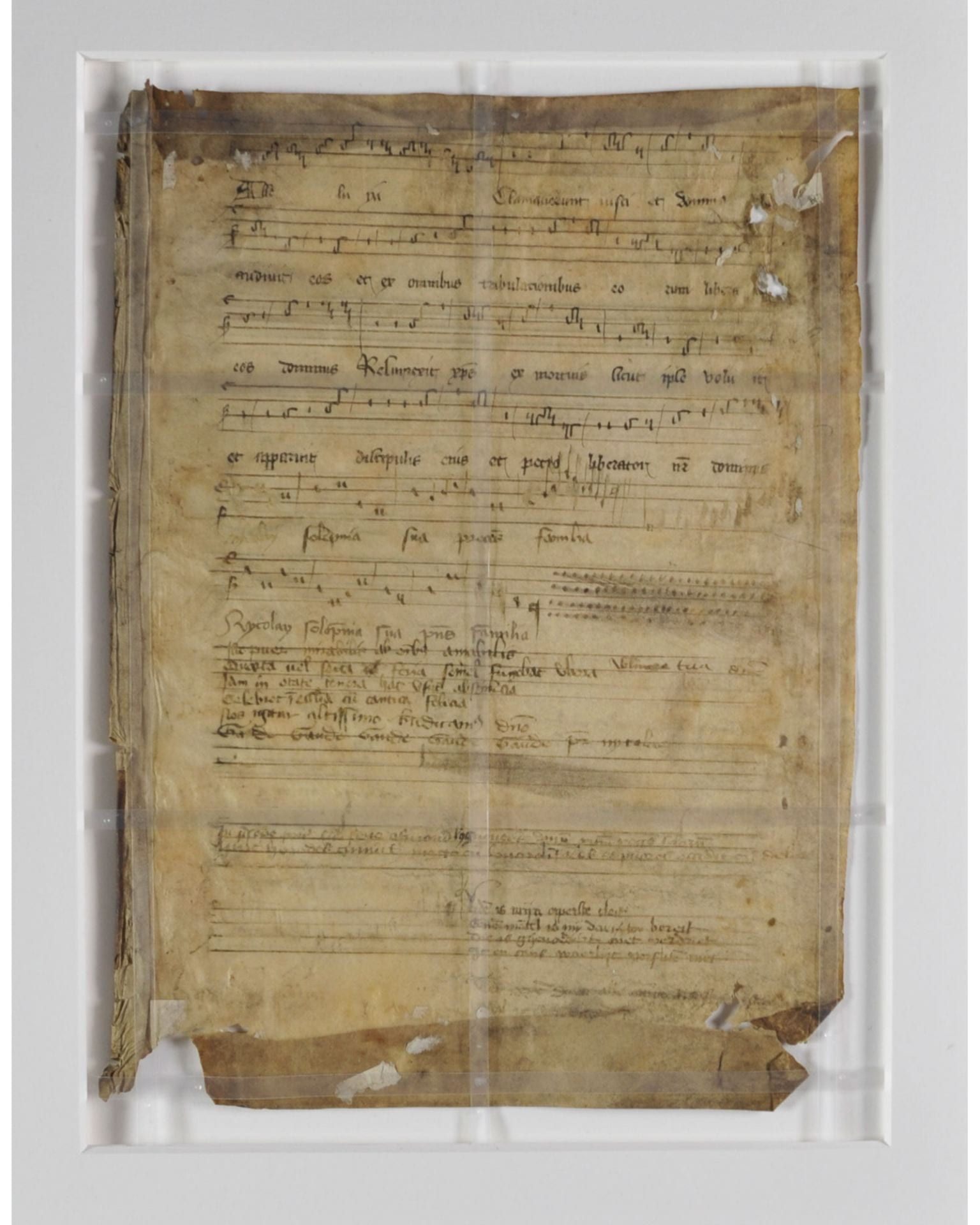

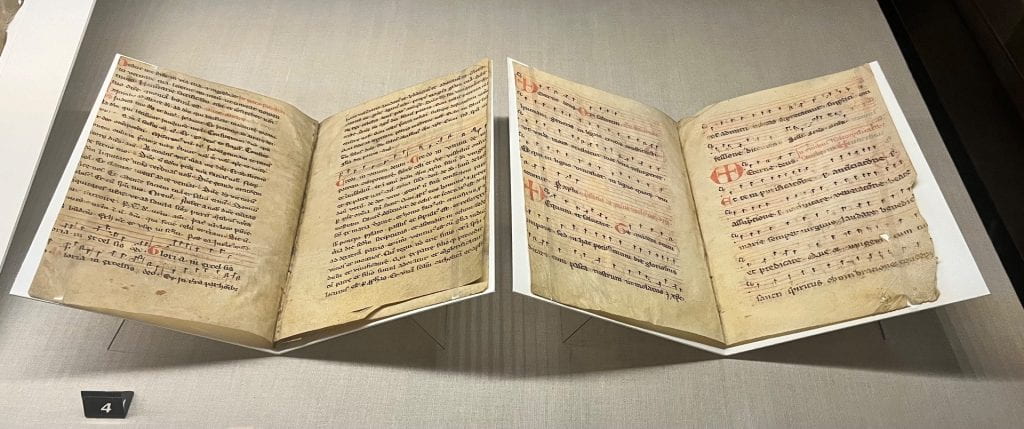

This uncatalogued volume is one of Northwestern’s most complex medieval treasures. Bearing witness to the intervention of several scriptorial hands, its present state is a fragmented mosaic shaped by centuries of ongoing adjustments—a testament to its active and enduring usage throughout time.

Believed to trace its origins to fourteenth-century Florence, Italy, this multifunctional choir book is a unique amalgamation of liturgical elements, incorporating pieces from the Divine Office and Mass for St. John the Baptist, and sections of a Requiem Mass or Mass for the Dead. The musical notation adheres to the standard squared notation for plainchant prevalent after the thirteenth century.

The fourteenth-century layer, corresponding to the first half of the manuscript, is adorned with gilded historiated initials, offering visual depictions, such as the iconography of St. John the Baptist, seamlessly accompanying chants dedicated to his feast. Subsequent interventions, spanning from the seventeenth to the nineteenth centuries, showcase the manuscript’s continued adaptation.

Signs of wear and damage, reflective of its active use throughout time, tell a poignant story. From modern calligraphy added beneath earlier Latin lyrics to the compilation of diverse chants for various festivities, the interventions in the book’s second half blend features of both modern and premodern notation. As such, this volume invites us to reflect on the resignification and relocalization of medieval musical practices and the performance of everyday spirituality.

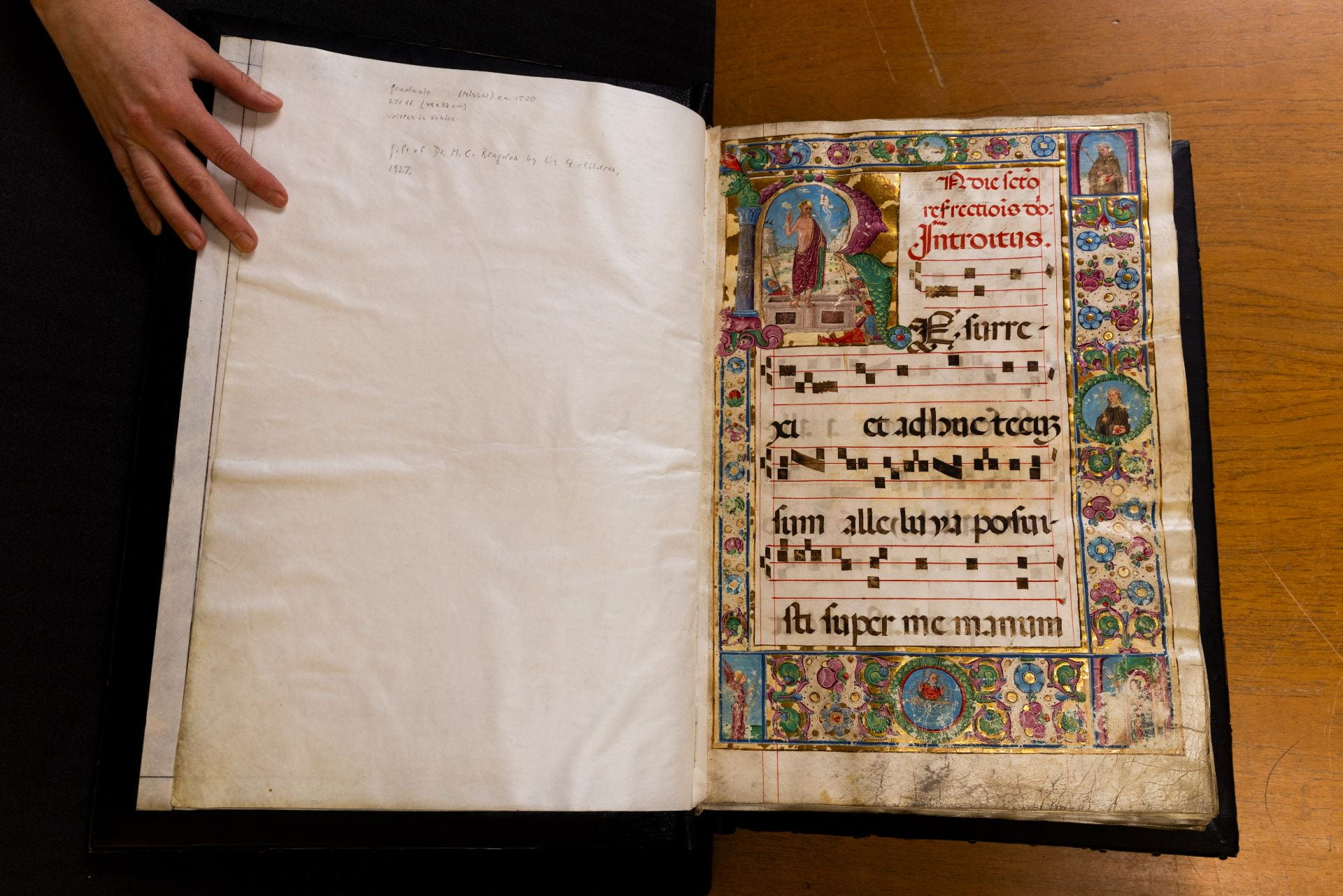

L2 Ms 43 stands as an exquisite testament to the cultural heritage of the northern Italian peninsula in the latter half of the sixteenth century. This voluminous choir book was likely crafted in Venice after the 1560s. The generous dimensions of L2 Ms 43 are indicative of its intended purpose — communal performance. A gathering of singers would have encircled the manuscript atop a large, specialized music stand, the Italian “badalone,” created for vocal performances within church settings. This Gradual compiles the musical components of the Mass, specifically the musical sections spanning Easter through the 24th Sunday after Trinity. The book also follows the dictates of the Council of Trent’s liturgical reforms (1545 to 1563), evident in its selection of plainchants.

Beyond its musical functionality, this Gradual served the purpose of performing grandiosity. Illuminated initials, opulent borders, and miniature illustrations collectively highlight the magnificence of the manuscript. Serving as a symbol of power and affluence, books like this were a costly endeavor, crafted by a team of specialists using parchment or vellum leaves, vibrant pigments, and adorned with embossed metal plaques based on religious iconography. The meticulous craftsmanship, inclusive of gilded elements, underscores its role as a conspicuous display of wealth. Such lavish volumes, thus, were not just items of religious significance but often served as diplomatic gifts. Rich institutions and influential patrons commissioned such musical manuscripts, underscoring the relationship between cultural artifacts, music performance, and the performance of power during this era.

Our heartfelt acknowledgement extends to Northwestern University’s library staff, Music Curator Greg MacAyeal, Head Conservator Susan Russick and the Conservation Lab, and this year’s Vagantes Committee from our Medieval Studies Cluster for their support in bringing this exhibit to life.