By Jess Ortegon

During our work to care for the physical aspects of Northwestern University Libraries’ collections, we sometimes find that objects require a closer investigation to consider treatment options. One such way that we do this is by using Multispectral Imaging (MSI), which includes several noninvasive imaging techniques capable of characterizing different materials such as adhesives, pigments, coatings, and even structural elements. We utilize MSI in the conservation lab primarily to learn more about the production of an object and use that information to help guide our treatment decisions—or avoid risky treatment altogether. A recent addition to the lab, the VSC80, has been key in helping us better understand what our collections are made of.

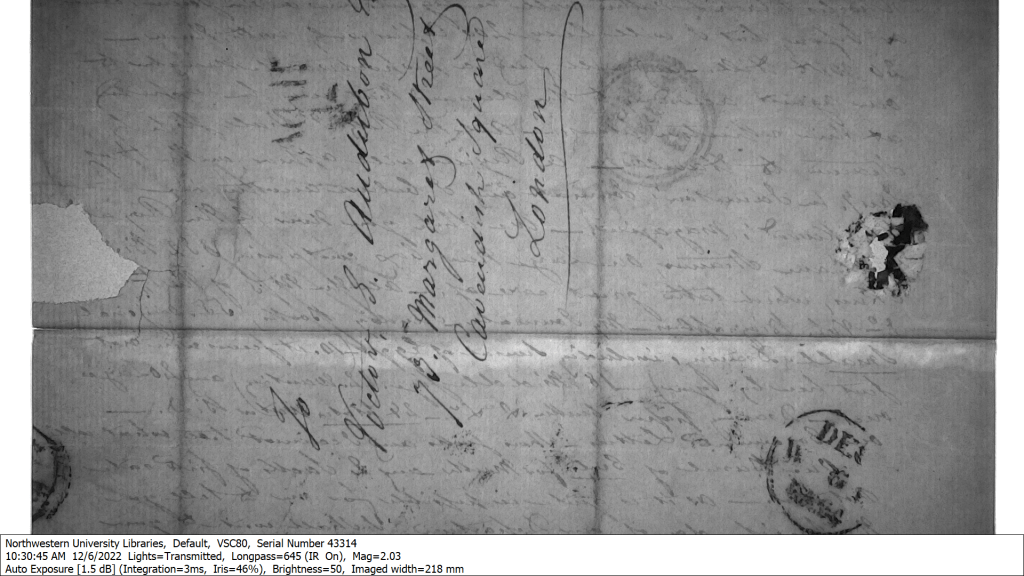

VSC80 station while documenting a manuscript from the Herskovits collection.

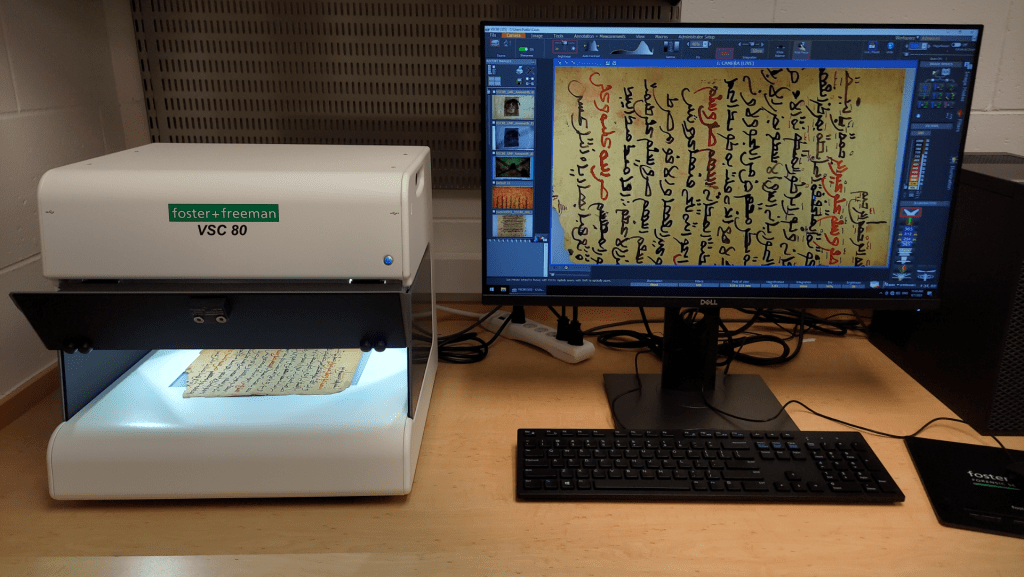

A look inside the VSC80.

Paper and Ink: Arabic Manuscripts

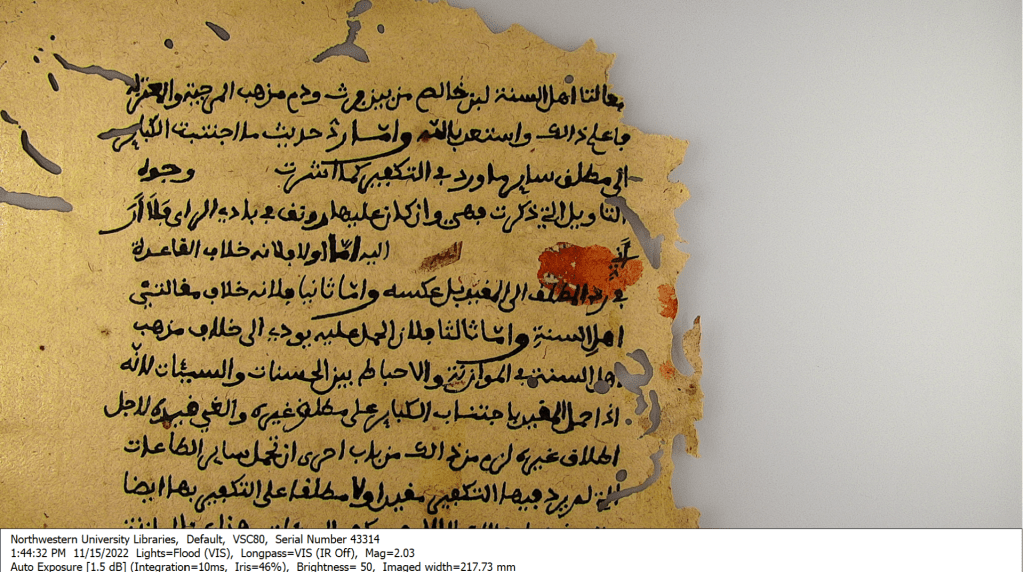

The Melville J. Herskovits Library of African Studies at NUL holds a collection of over 5,000 Arabic script materials from West Africa, most in Arabic and some in ajami — African languages such as Wolof, Fulfulde, and Hausa written in Arabic script. The collection dates primarily from the 19th and 20th centuries and boasts a wide range of subjects from poetry to law. This collection is a valuable resource for scholars and as such has been the subject of an ongoing conservation project where we are analyzing the manuscripts’ papers and inks.

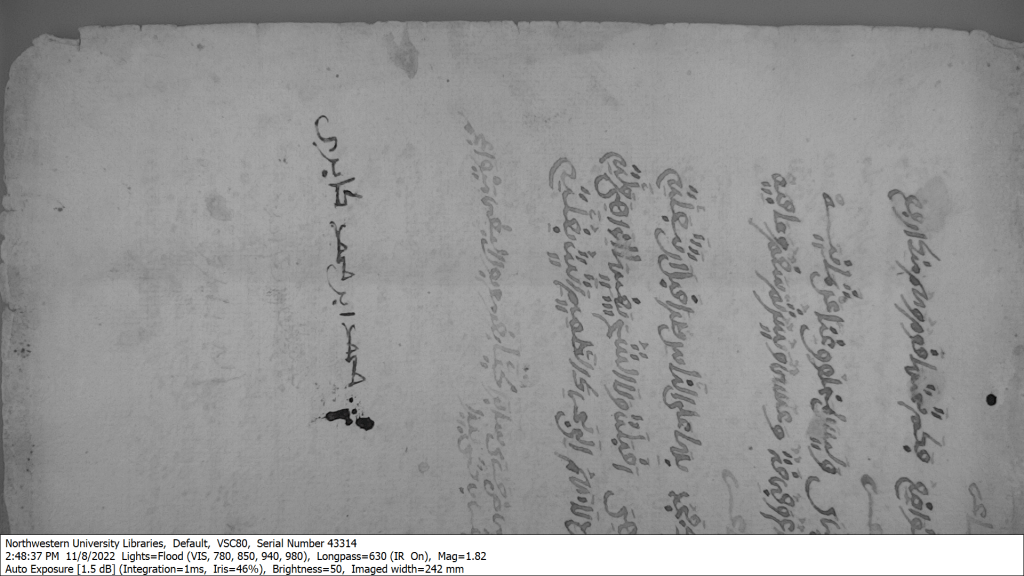

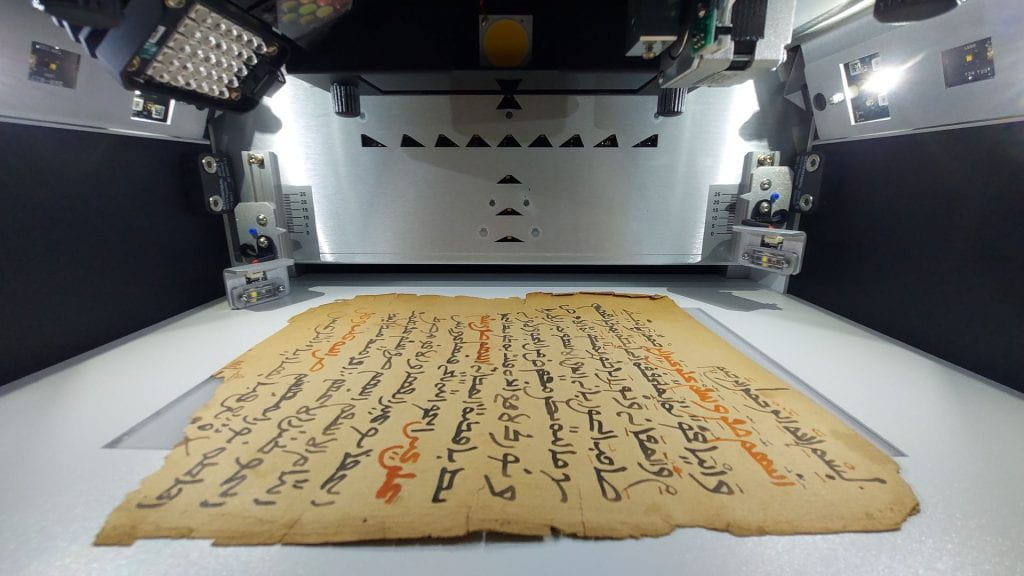

Various Arabic manuscripts from the Herskovits collection.

While many of the bindings are similar, the contents of each manuscript are unique.

Our goals for analysis are to record observations on the physical characteristics of the papers, note any watermarks, and analyze how the inks behave under MSI. The results guide conservation treatment decisions and are provided to researchers to study the provenance of the materials and contribute to a growing body of research on West African manuscript production. We’re using the VSC80 for all of our analysis in this project as it’s able to replace multiple pieces of equipment used for each MSI technique (light tables, UV lamps, specialized IR cameras). It also has consistent, reproducible results, which is very important when recording and sharing results from such a large collection.

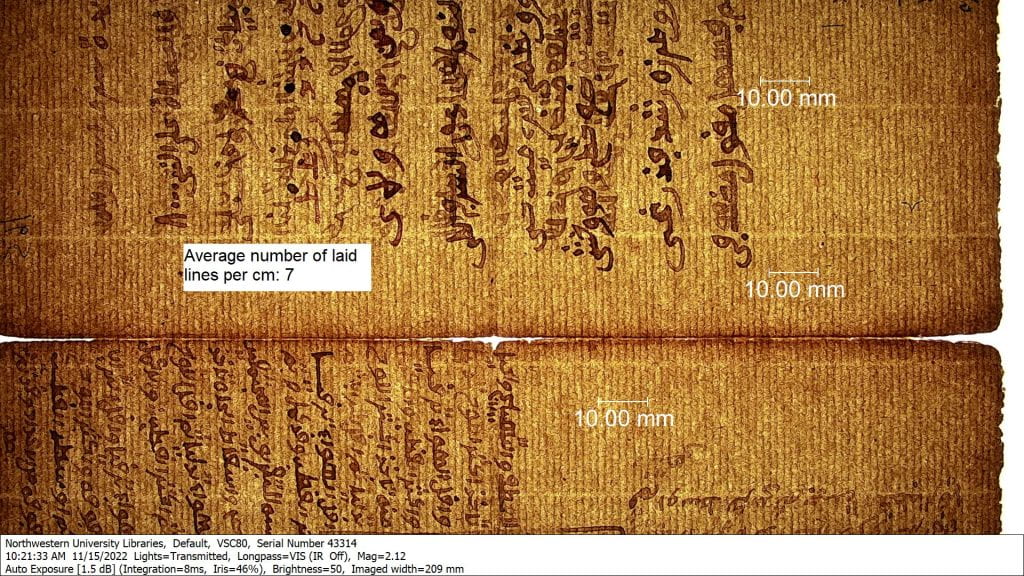

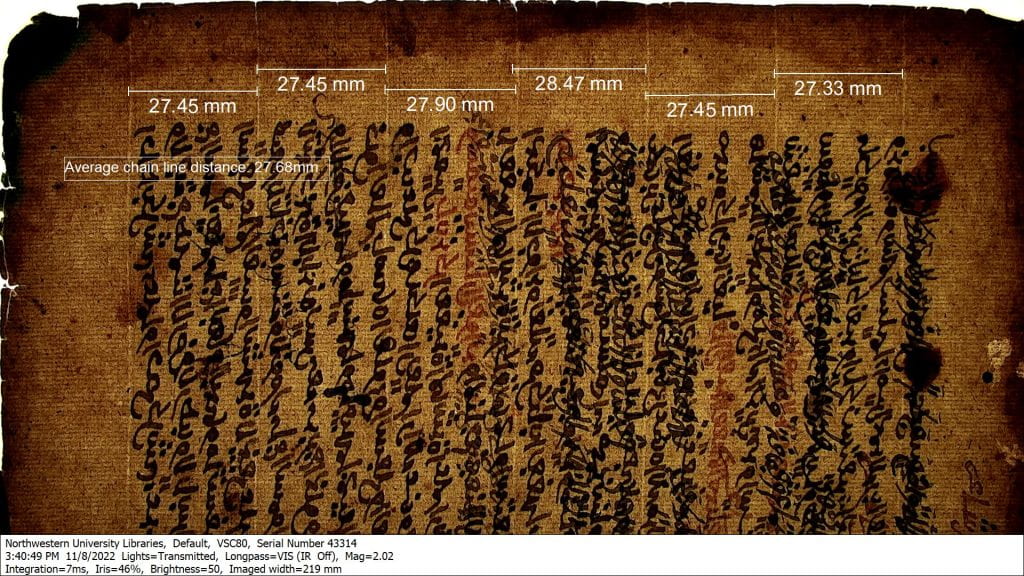

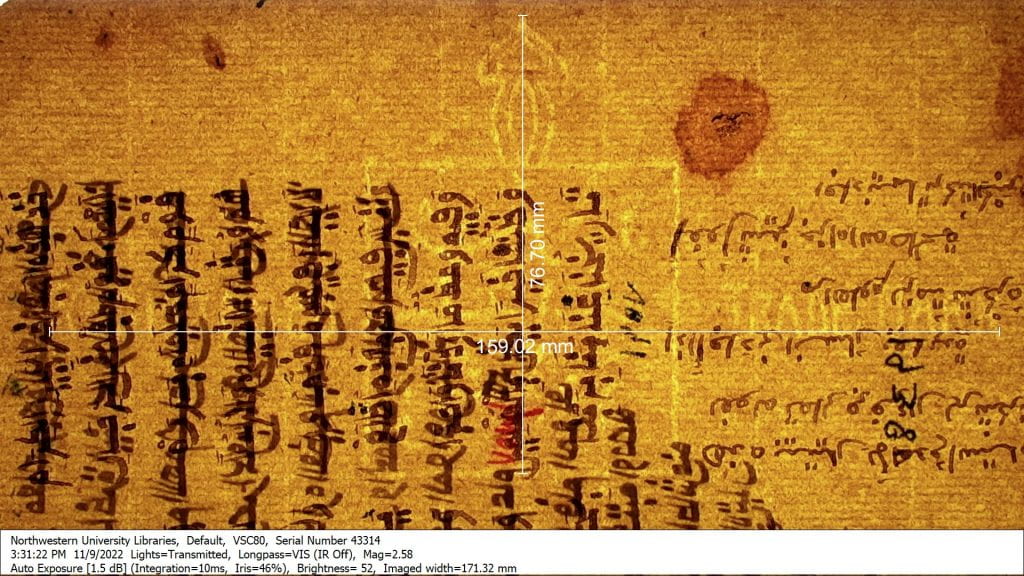

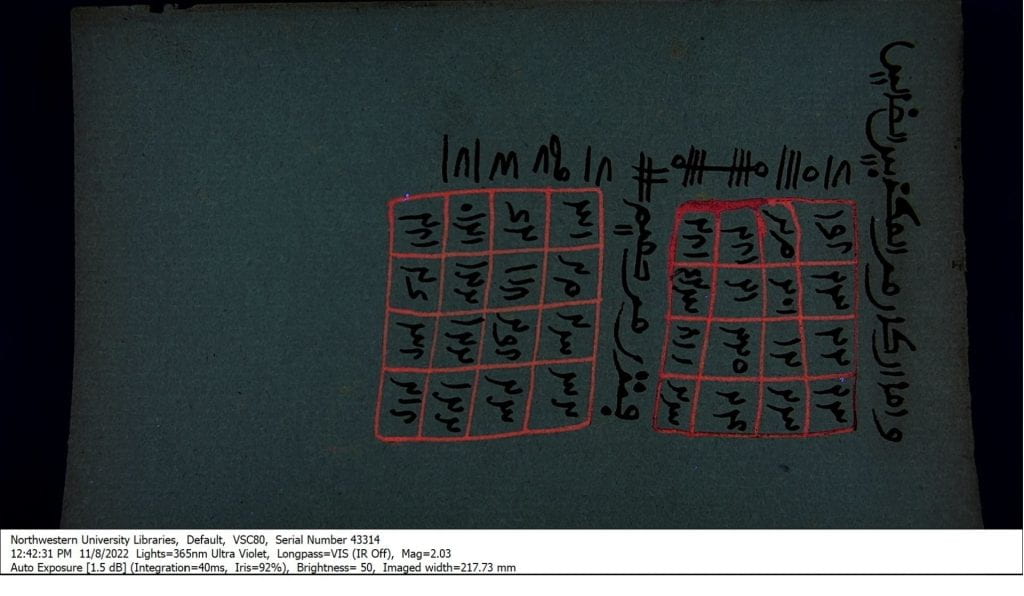

First, we examine a manuscript page using transmitted light to reveal physical characteristics of paper resulting from the manufacturing process such as laid and chain lines or watermarks. The VSC80 magnifies, measures, and annotates images, which we use to note the number of laid lines per square inch, the distance between chain lines, and the size of watermarks on the paper. Watermarks such as the Tre Lune (three moons), can point to the geographical source of a paper, as well as pathways of trade and commerce, providing a more detailed background to the types of paper used for each manuscript.

Different watermark examples, including half of a Tre Lune, and annotated measurements of chain and laid lines.

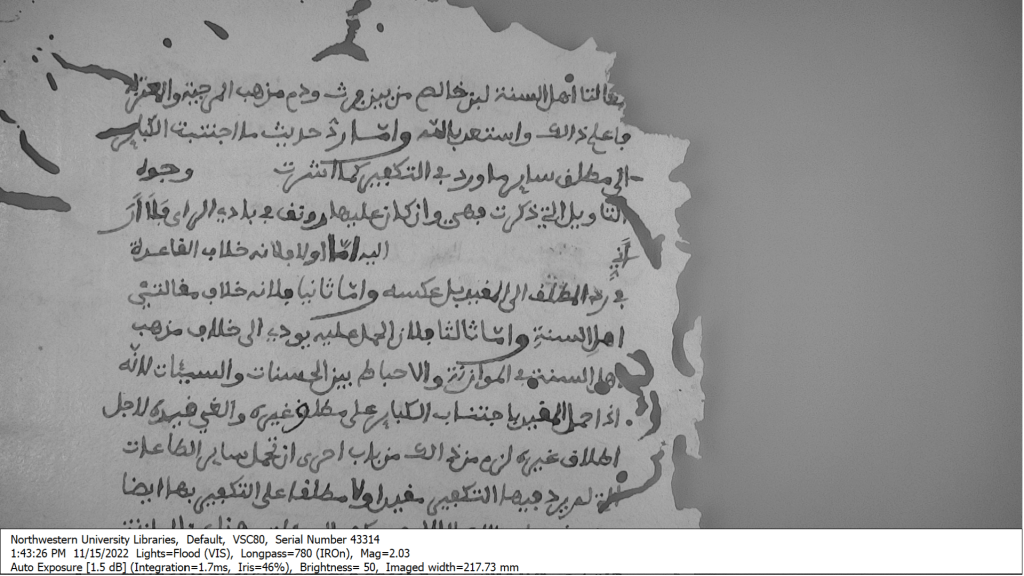

After looking at the paper, we next analyze the inks using UV to observe any fluorescence (glowing), and IR to observe if the inks remained visible, which indicates if they absorbed or reflected IR radiation. The VSC80 also has a feature where it records important information about each technique we use directly into our photographs, so we can always go back and look at a certain ink using the same parameters. While we aren’t usually able to identify inks with certainty, we can note if there are similarities and differences among them. For instance, we may be able to see that two red inks react the same under MSI, suggesting that similar inks may have been used either in one manuscript or across many. Studying these inks can also inform our conservation decisions and help support observations from scholarly research.

Different manuscript inks under UV and IR radiation.

Revealing Hidden Text: Audubon Letter

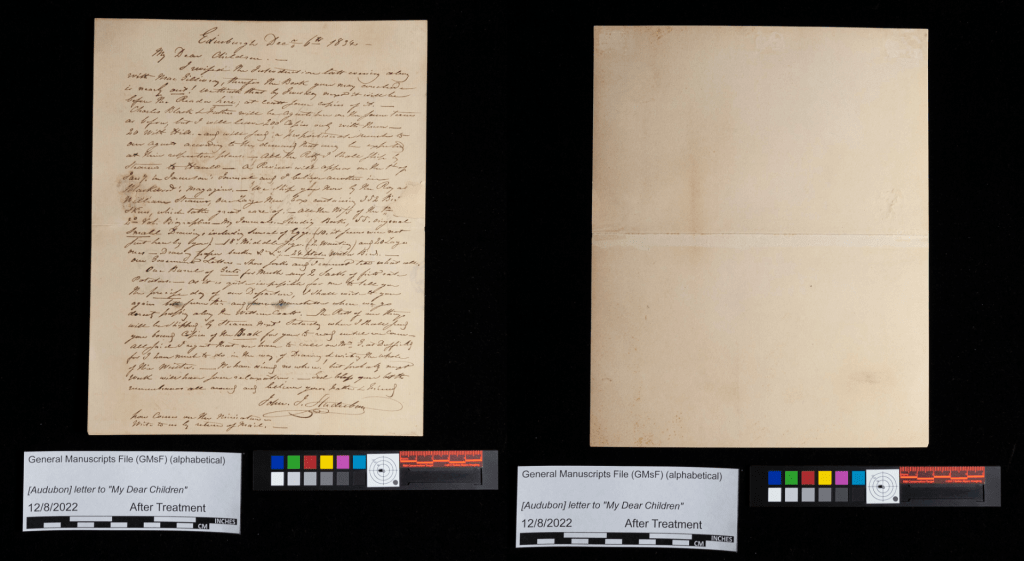

MSI can also be a useful solution when considering treatment for an object, such as in the case of a letter from John James Audubon to his family. This handwritten letter came to the conservation lab from the McCormick Library for Special Collections and University Archives as part of a larger project focused on the digitization of Northwestern’s General Manuscripts collection.

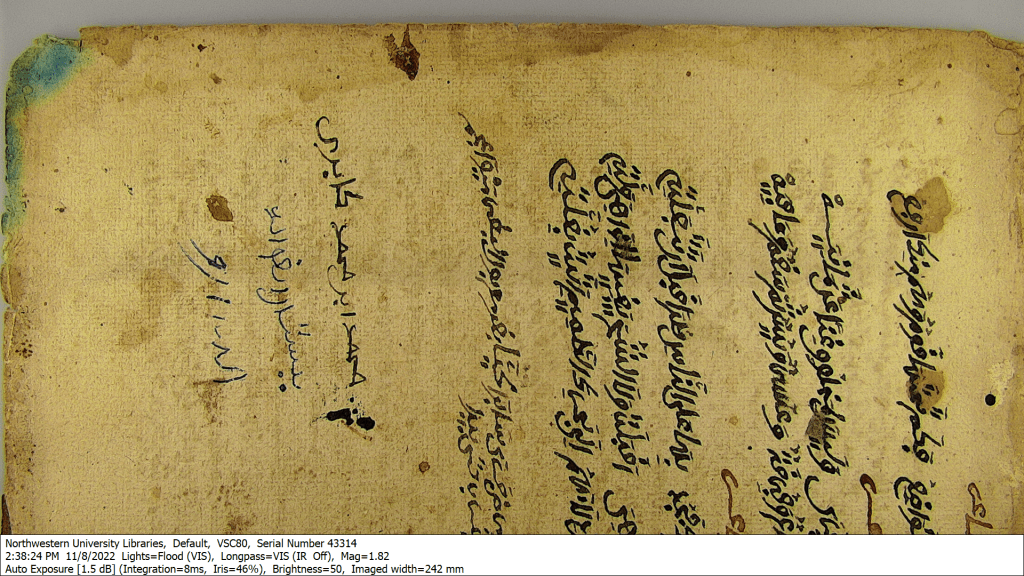

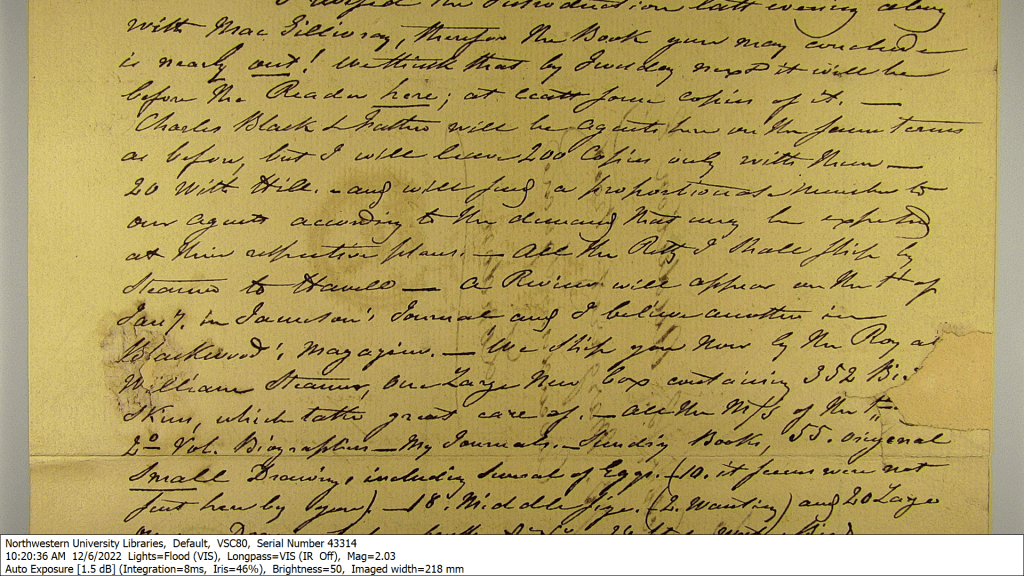

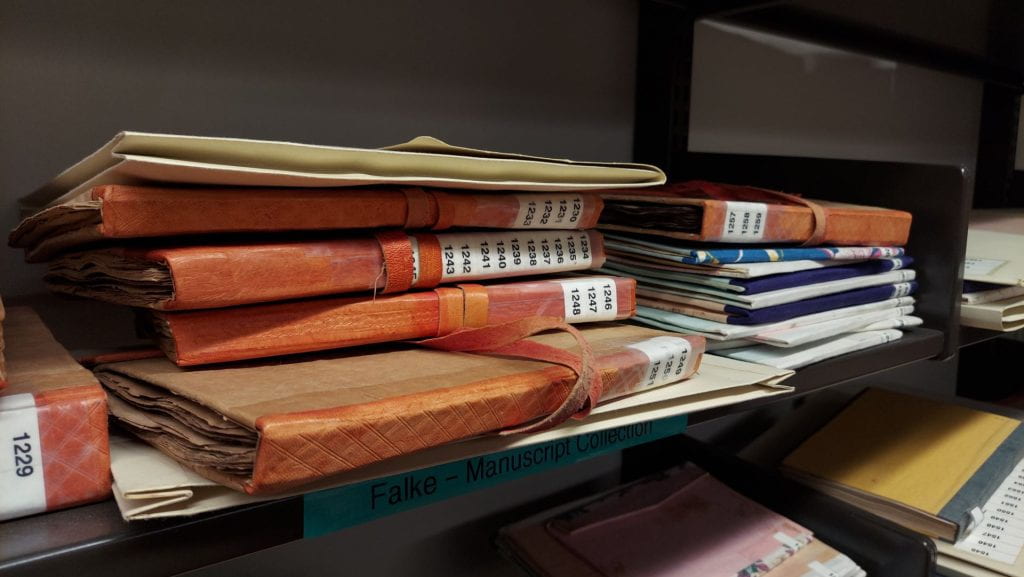

Overall view of the letter from John James Audubon to his family.

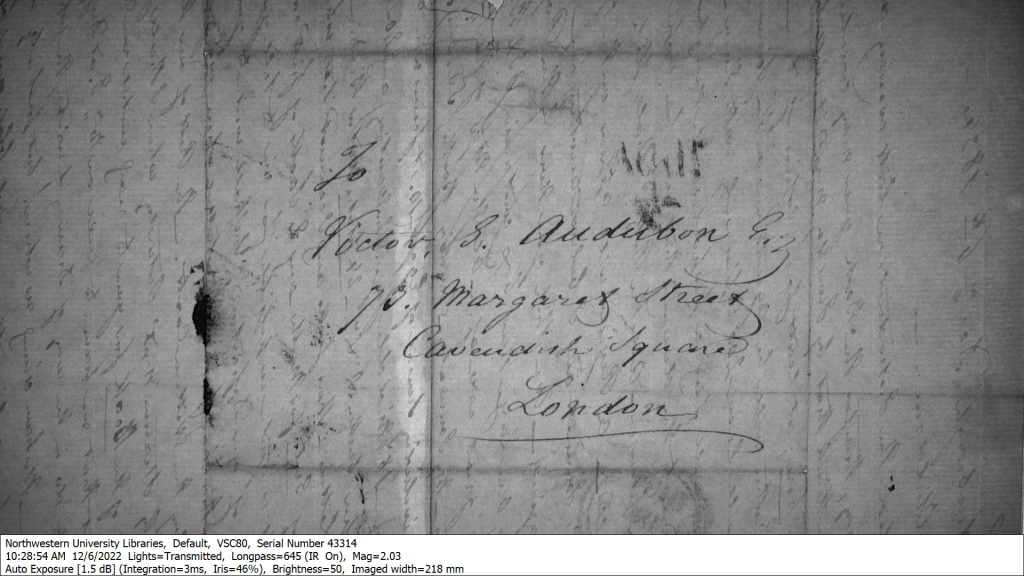

While inspecting the letter for documentation, it was discovered that the letter had been lined or adhered to another piece of paper. This was done to repair previous damage and likely strengthen the letter overall. However, the lining prevented us from seeing the address of the recipient, stamps, and seal used to send the letter. Due to the importance of this information, we considered removing the lining from the back of the letter. However, the inks show signs of being water soluble and any effort to remove the lining could result in further damage.

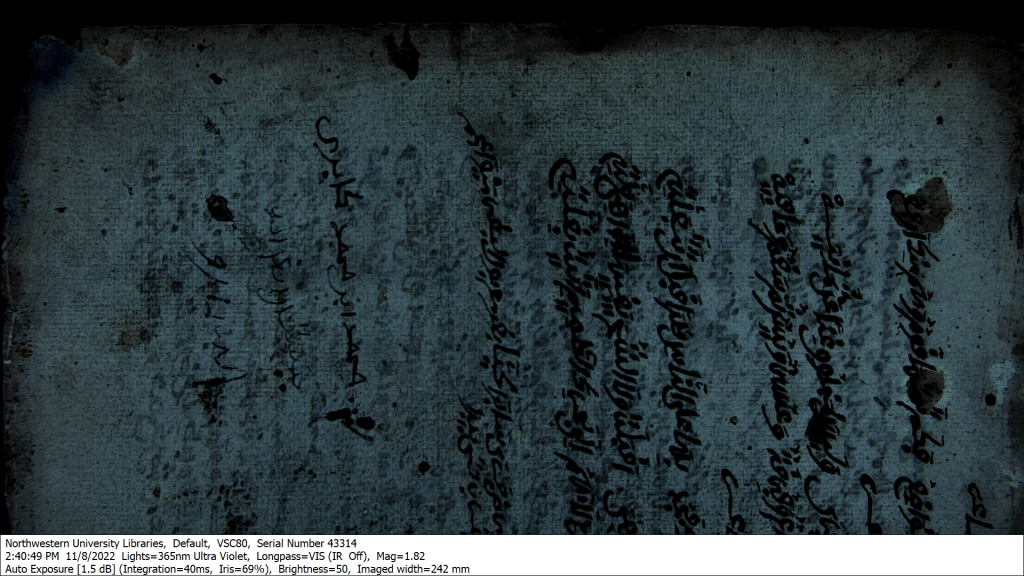

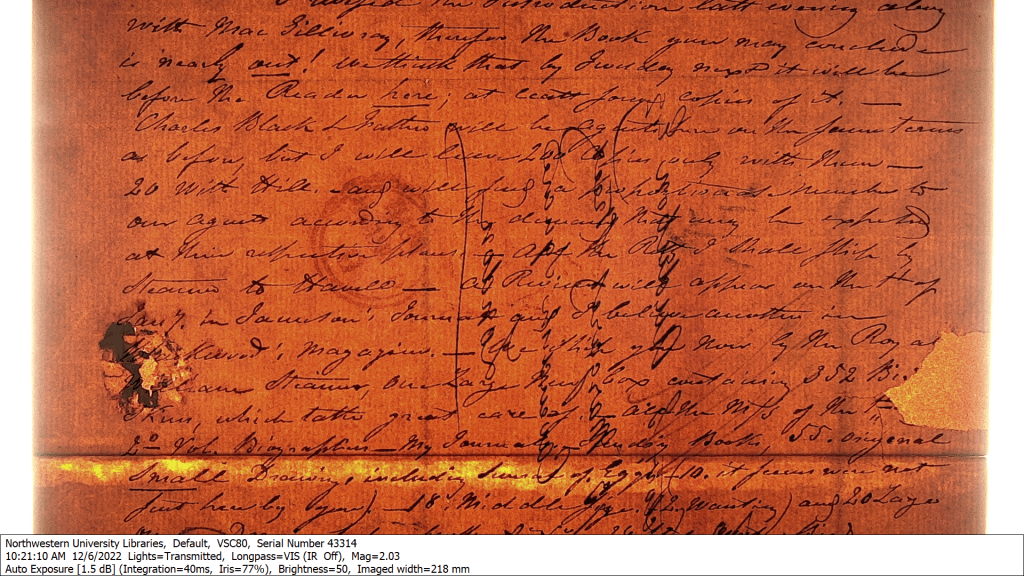

So, what could be done? MSI, of course! The address was first observed using transmitted light to help to identify its exact location on the back of the letter. However, it was difficult to capture a clear image of the address by using just transmitted light since the text of the letter was still visible. Using the IR filter capabilities of the VSC80, we were able to observe the address more clearly by isolating it from the text. These filters isolate how materials react at precise radiation energy levels, which allowed us to observe and capture images of the address as well previously obscured stamps and original fold lines.

View of the Audubon letter using different radiation. Notice the address on the back of the letter shows using transmitted light.

MSI was a great success, circumventing potentially invasive treatment and providing important information about this letter. Additionally, the images from analysis were printed out and housed with the object in its permanent folder so that future researchers also have access to this information.

The address and the stamps revealed.

Conclusion

The VSC80 and its MSI capabilities is an excellent tool for contributing material analysis to our collections here at NUL. Analysis of the Arabic manuscripts is still ongoing, but new projects, such as pigment analysis of a 20th-century Ethiopian parchment manuscript, present new and exciting challenges. Our observations and analysis using the VSC80 will help to better contextualize the materiality of our collections and continue to mitigate potentially risky treatments. Eventually, we hope to make the VSC80 images available online alongside the objects’ digital records. We will share more of our discoveries soon!