Happy Preservation Week! It’s the best time of year because it’s an opportunity to talk endlessly about what preservation is and what our department does.

Preservation is an umbrella term for activities that take care of collections – this includes conservation treatment, environmental monitoring, custom housing (boxing), book rebinding, pest management, mass deacidification, exhibit and loan preparation, and more! Here’s a quick dive into some other activities.

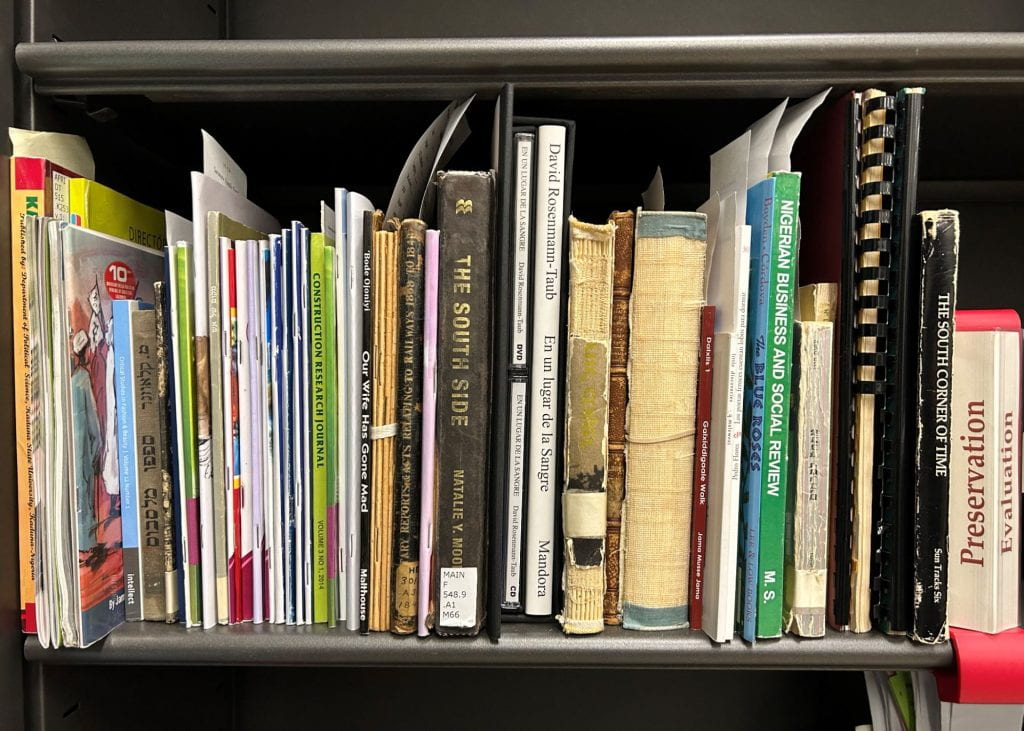

Preservation Evaluation

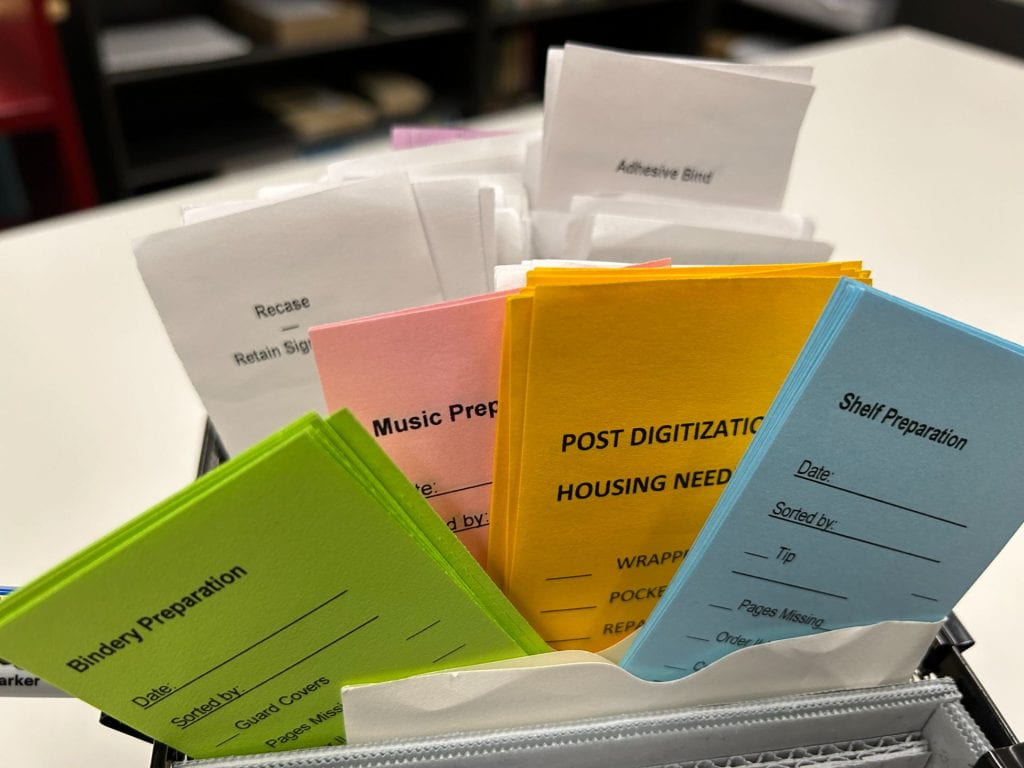

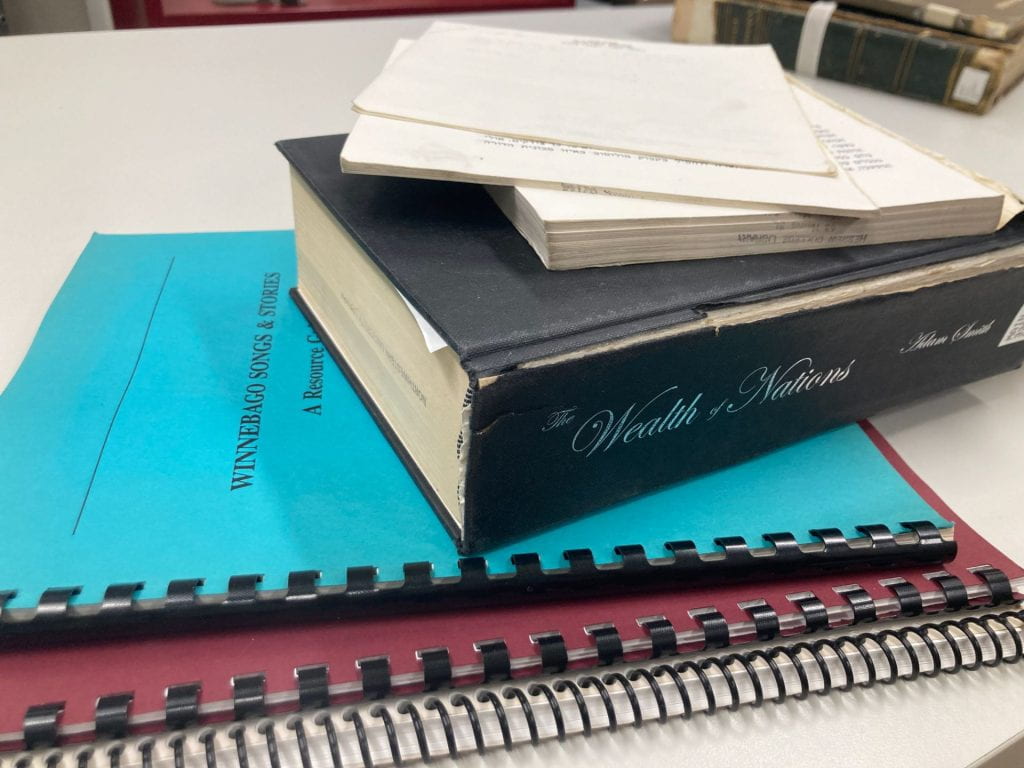

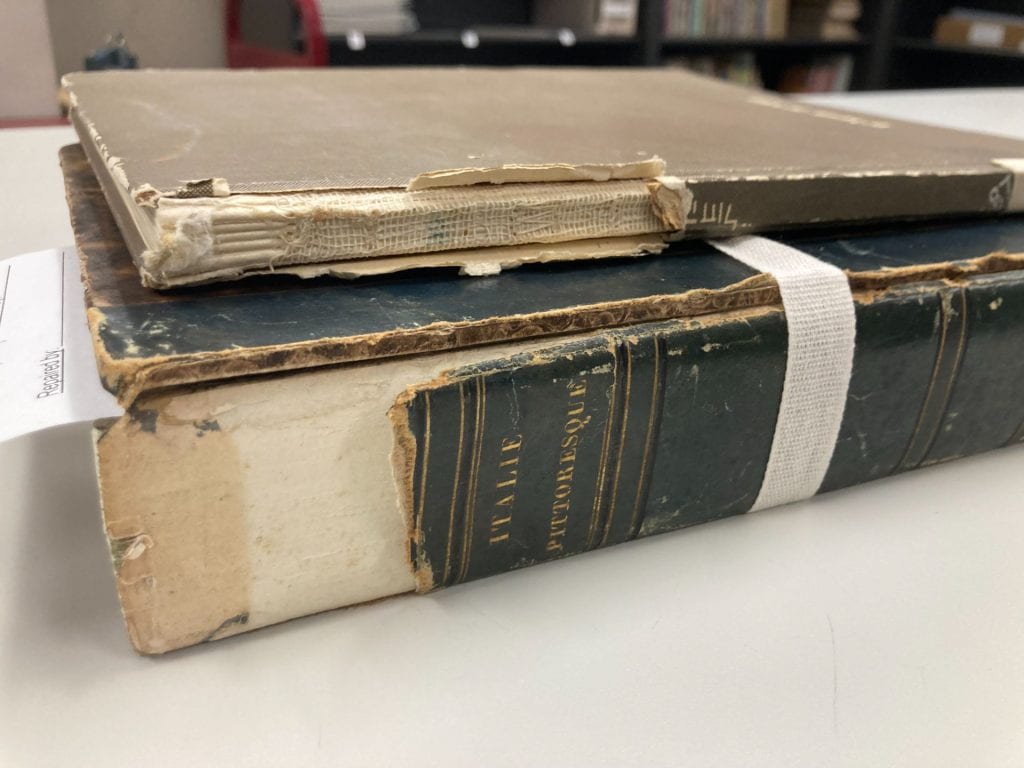

Every Monday morning, a few of us go through the circulating books that need some kind of preservation attention. These materials come to us from circulation, catalogers, and alert colleagues. We evaluate the items and decide what general category each fit into: commercial binding, brittle books, replacements, shelf and bindery prep, or conservation repair.

Books we send to the commercial bindery (an out-sourced bindery) need new covers, may be too thin or flimsy to stand upright on the shelf, or are a thick single-signature pamphlet. Books bound for conservation repair may be older or have more artifactual value. Books that need replacing (due to damage from patrons, water, or mold) are assessed and usually passed along to our Acquisitions coworkers.

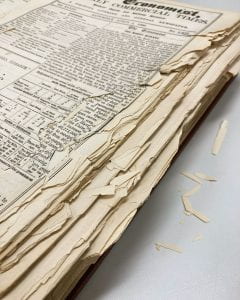

Brittle book pages breaking off

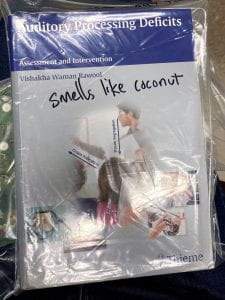

Book that will be replaced

Damaged binding with tape repairs

Circulating book-object needing a box

Shelf preparation is a category of lab work that covers a lot. Errata are tipped in, supplements get a custom pocket, pamphlets are sewn into binders, uncut pages are sliced, and a pile of random objects that are apparently an art book get a special box. We see it all, and it all needs to sit on a shelf!

Washing paper

Yes! We put paper in water on purpose! Washing is a conservation treatment in which paper is exposed to water to both remove degradation products and add alkaline buffers and sizing. Overall cleaning lessens stains, washes out acidic compounds, and strengthens the paper fibers. Adding alkaline chemical buffers to the water can penetrate the cellulose and slow further paper deterioration. Washing involves a lot of chemistry, from using deionized water to raising the pH to adding a resizing agent. Some chemical compounds are used for lightening paper, others add specific levels of alkalinity.

Removing a newspaper from a bath

Before washing, the materiality of the item must be examined for suitability. Water-soluble inks may run or have possible chemical reactions. Each item is spot-tested to confirm its ability to withstand a bath. Ethical considerations about altering the item also play a role in treatment decisions. Visible and chemical changes to papers, such as lightening and changing pH levels, may not be appropriate.

Several prints in a bath

A dinosaur salt shaker with pH strips

A large poster drips water that shows acid and dirt from paper

Washed and lined maps drying

Paper is placed on a thin piece of spun polyester fabric before being wetted. The water keeps the item “stuck” to the fabric and is fairly secure. This supports the paper since it’s more vulnerable in the bath. It also makes it easier to take in and out of baths and drying racks. After the washing process, papers can feel stronger and look cleaner, which is the goal!

NOTE: For best results, do not try this at home.

Inspecting incoming collections

Inspecting boxes and folders

Sometimes the library acquires books and archives that have been kept in garages, basements, attics, or storage units. This situation happens enough that we have formed workflows around incoming collections to check for preservation issues, such as mold or pests. We set up an inspection station on that includes large sheets of paper covering the table, some brushes to wipe away dust, a HEPA vacuum cleaner, zip-close plastic bags of all sizes, new archival boxes and folders, and gloves. Definitely gloves.

We look through folders, boxes, or books, paying particular attention to anything that has evidence of water damage. The crease of folders, inside the cover of books, and folds in papers are places where mold, pests, and dirt tends to hide.

Evidence of mouse activity

Inspection station set up

Disaster preparedness and response

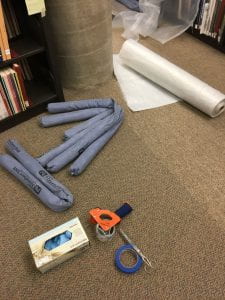

Pipe leak in the ceiling? Downpour while emptying the book drop? Polar vortex-caused “inside ice” that melted? We’ve seen all these things and more. Luckily the Preservation Department is stocked up, prepared, and experienced for “clean up in aisle Library.” Plastic sheeting is used to drape over shelving that is under a leak. Rain socks soak up any drips down the plastic. We also maintain the Disaster Handbook, which is placed in each department, and created a Disaster Response guidelines poster. The poster includes emergency contact information and directions for covering shelves with plastic.

Draping the shelves with plastic sheeting to cover the books

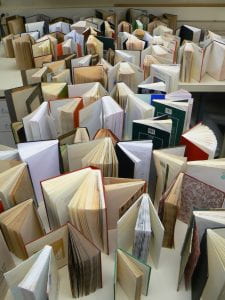

Books fanned out to dry

The necessary supplies to cover shelves

Wet books and papers are quickly taken to the conservation lab and fanned out to dry. Books with clay- or polymer-coated pages need immediate interleaving between each page or else they will permanently stick together. If the water disaster damaged more items than the department can quickly handle, we call in a vendor to freeze and slowly dry the books.

BIG high fives go to the staff and students in facilities and building safety, who are frequently the ones to come across leaks and spring into action. Also worthy of a shout-out: library trash and recycling bins that are invaluable leak buckets.

Cleaning Mold

Mold happens. In every library. It can grow on books that got wet due to an undetected leak, or it was on a collection when it arrived. Since we know it happens, our focus is on how to remediate and prevent it. We decide what cleaning we can do in-house, depending on staff time and amount of mold, and what we will need to send to a vendor for remediation.

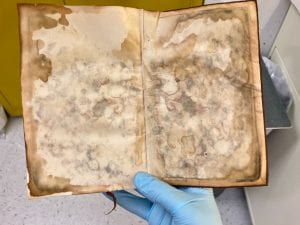

Water damage and extensive mold

Books next to each other on a shelf where mold grew between them.

Sometimes materials are too damaged to safely retain. If this happens, we ask the following questions: Is a replacement available? If not, has the material been digitized so we can withdraw the item? If not, can we clean the item as best as possible, digitize, and then withdraw? If not, can we withdraw the material anyway? We discuss these options with collection liaisons and curators and find a solution. Each item is a bit different.

This is just a small peek into what our department does beyond “fixing the books.” Everyone in Preservation has unique experiences and skills that allow us to do such a wide range of activities.