When you think about a book of recipes, what word comes to mind?

The answer to that question is most likely, “cookbook.” It may surprise you to learn that until 2010, library catalogs were still using the term Cookery for a book of recipes, instead of the word Cookbook. This terminology choice made sense in the late 19th century. As the years went by, the term persisted in the library well past the time it became outdated. In libraries, our systems are designed to adhere to rules—this helps us be consistent and organized. By using consistent terminology, researchers have an easier time finding all the information on a topic in one place. The downside is that change is slow and time-consuming. This can lead to archaic, clunky, and sometimes even offensive and derogatory terminology in the records you see in our collection.

In Fall of 2020, the Metadata Inclusivity Steering Group was formed at Northwestern Libraries to lead projects to address issues of offensive language in our metadata in our metadata. We wrote a Statement on Bias in Library Description and included a form where users could submit concerns about our metadata. Metadata is the language used in Northwestern University Libraries’ (NUL) catalog, online tools, archives, and digital collections to describe and manage resources and enable their discovery and ongoing access by the scholarly community. In this blog post, we want to elaborate on a few reasons why our metadata can include problematic words, why it can be challenging to reform our practices, and what is being done to make improvements.

Records might be old and have out-of-date terms

Some of the information in our records can be archaic in surprising ways, like Cookery. This is because our metadata is often decades old. The card catalog was invented in the 19th century to make materials discoverable in a continuously growing collection. For each book, cards were written and added to the catalog drawers in three places: alphabetized by title, author, and subject. Cataloging a book was final: once it was done, you moved onto the next one.

The card catalog “went online” (also called automation) by converting the cards to computer files. This means that records for long-held items are transcribed versions of cards that were created decades ago. Automated updates may enhance the records, but the metadata that libraries use in our contemporary collections are often from an earlier time. Since society’s understanding of social issues evolves along with our language, our records can be out-of-sync with our current values.

Since catalog records utilize subject descriptions to help users discover materials, we still need controlled vocabularies to ensure we are always using consistent terms. The largest and most widely used vocabulary is the Library of Congress Subject Headings (LCSH). LCSH originated in 1898 and continues to be updated on a monthly basis. It tells us what preferred term to use: i.e. Firefighters, not Firemen; Lawyers, not Attorneys. A controlled vocabulary helps us be consistent, but it makes it difficult for the terms to evolve quickly. Even when describing a new book, we often use subject headings that were chosen in the distant past.

The resources themselves can be problematic

Academic library collections contain millions of books and other materials. Older materials are of great use to historians and other scholars—but this does mean that we have items in our collection that are written from a prejudicial perspective. However, library catalogers do not have to mirror the offensiveness of the work we catalog to do our jobs well.

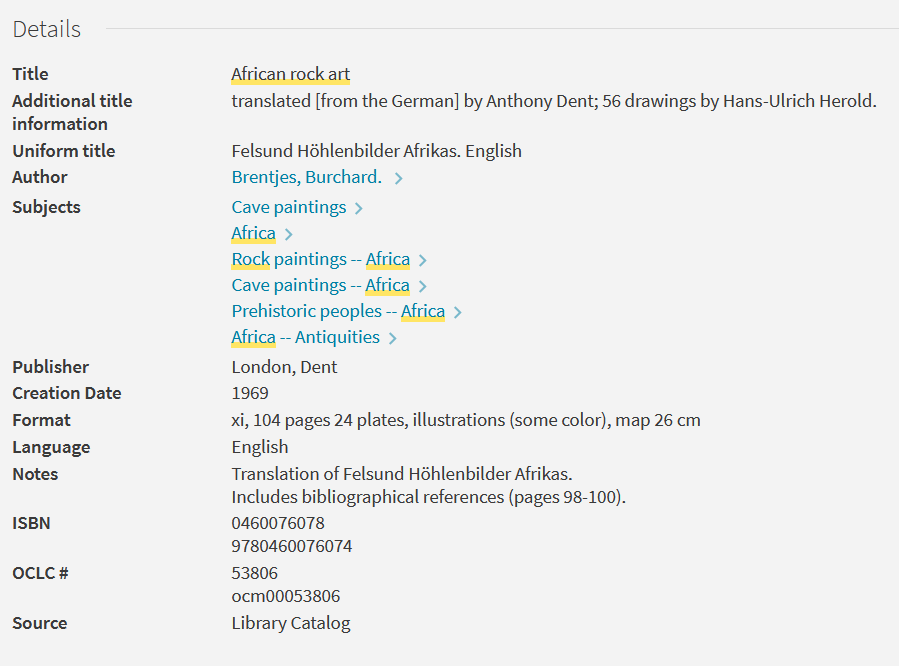

In the past, catalogers were asked to be neutral when choosing subjects. Unfortunately, if you are neutral while describing something offensive there is a good chance you will end up affirming that prejudice. Until recently, the term Art, Primitive was still in use. The term was applied to books on art from Africa and art by Indigenous Peoples, even when more accurate terms were available. For example, our record for the book African Rock Art (Brentjes, 1969) originally had the subject Art, Primitive, even though it would have been sufficient to only use the subject Cave paintings–Africa. It was the choice of the cataloger to add “Primitive,” likely because it reflected the point-of-view of the author. Catalogers have an ethical obligation to consider the subject headings we choose carefully.

We are part of a shared cataloging environment

Northwestern Libraries is part of an international cataloging ecosystem. We have standards and practices led by organizations like the Library of Congress. The records we use are created in a large, shared repository called WorldCat. When a book arrives, the cataloger will check WorldCat to find an existing record. If one exists, it will be downloaded into our system. If no record exists, the cataloger will create a record, and that record can be used by other libraries.

There are many benefits to this system, particularly in saving staff time. It also means we share standards and vocabularies with a broad array of institutions. Working in a shared environment means there is a tradeoff between efficiency and customization. We cannot make up our own standards, because we agree to share our records with others.

NUSearch, where you look for items in the Northwestern collection, is much more than an online catalog: it’s a discovery system. It includes links to online materials, journal articles, and more. Much of the metadata is added directly into NU Search and cannot be edited by library staff. The quality of the records in the discovery system can vary from good, to inaccurate, to even offensive. By allowing those records in, we open up the possibility of low-quality metadata appearing in NU Search results. However, if we excluded these records, it would make it difficult for our users to discover materials.

What can be done to improve our metadata?

While there are many barriers to change described above, metadata creators can do a lot to mitigate the problems. Here are a few examples of what can be done:

Use a Variety of Subject Vocabularies

Originating in 1898, the LCSH vocabulary is the largest list of subject terms available. While it is the largest and most common one in the United States, it is by no means the only vocabulary available. There are discipline-specific vocabularies and vocabularies created by the communities being described.

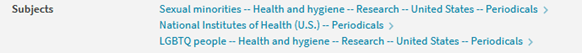

One such vocabulary is the Homosaurus, a linked data vocabulary created for LGBTQ terminology. At Northwestern, we are beginning to add equivalent Homosaurus terms in records that use the LCSH term Sexual minorities. While Sexual minorities is not necessarily offensive, it is not commonly used by the LGBTQ community to describe themselves. In the below example, LGBTQ people was added from the Homosaurus vocabulary.

Propose Revisions to Library of Congress Subject Headings

It is possible to submit proposals to revise Library of Congress Subject Heading terms so they fit in better with our current values. In recent years, the Library of Congress has updated many subjects, including revising “Brothers and sisters” to “Siblings,” and “Mental retardation” to “Intellectual disability.”

Librarians at Northwestern have submitted proposals to revise LCSH headings to make the existing vocabulary more inclusive. Librarians at the Galter Heath Sciences library successfully proposed changes to LCSH terms about Giants to differentiate tall people with a pituitary gland disorder and fictional beings. We are currently undergoing a large project to revise the use of Cults in LCSH where the term Religion should be used instead.

Utilize Technology to Make Changes

Increased advocacy has led to our vendors providing more features that enable this work. In NUSearch, the term “Illegal aliens” displays as “Undocumented immigrants” because we utilize a local customization tool.

Our library systems vendor, Ex Libris, allows us to mute certain words so they do not display in NUSearch. This allows us to block terms from public display that are clearly offensive on records we are not able to edit. This still allows these terms to be used by researchers to find results of historical or outdated material that might use these terms—they’re still in the back end of the data even though they aren’t displayed publicly.

Furthermore, technology has allowed us to collaborate better across institutions. There is a community of metadata creators (Critical Cataloging, or #critcat) devoted to this work. Ideas are shared using the #critcat hashtag on Twitter and on the website Cataloging Lab.

A Shift in Priorities

There is a wider movement in the library profession to remediate issues with metadata used to describe our collection. Even though there are many challenges to this work, it is worthwhile, and we are committed as Northwestern Libraries staff to putting in the work to make this change happen. In a large collection like Northwestern’s, it can be a challenge to track problematic language in our records. If you see problematic terms in the catalog, or you have any other questions or concerns, please submit via this form or by email to Jamie Carlstone, Authority Metadata Librarian at jamie.carlstone@northwestern.edu.