The cover of a map of Grand Teton National Park. Box 2 Folder 14.

The National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 fully came into effect in January of 1970, and with it began the age of Environmental Impact Statements. While you may not know the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 as well as the Clean Air Act and Clean Water Act, it was a monumental bill that significantly increased the evaluation, prediction, and recording of government projects’ impact on the environment.

Environmental Impact Statements are reports that federal agencies are required to write before proceeding with any project that may have a significant impact on the environment. These reports give the government and the public detailed information on these projects and alternative actions, as well as the opportunity to weigh in through public comment, which is published in the final draft of an EIS. EISs provide an important record of executed and potential projects and provide activists and historians with a rich source of information about how federal agencies evaluate and weigh harms. (If you are interested in using EISs in your own research, please see the Transportation Library’s research guide on accessing them).

A pamphlet educating Minnesota residents about radioactive waste from Box 4 Folder 10.

One question that has always surrounded EISs is whether they are accurate in their predictions. They are made before projects start and by the agencies and companies involved in the projects, as well as made under a time limit, so there are many ways in which the outcomes they predict might not be the outcomes that are seen.

To tackle that question, former Northwestern Professors Paul Culhane and H. Paul Friesema, along with then Ph.D. student Janice Beecher, embarked on a study of Environmental Impact Statements and got funding from the National Science Foundation to proceed with their work in 1981. What emerged from this academic research was one published study, three conference presentations, and one book entitled Forecasts and Environmental Decisionmaking: The Content and Predictive Accuracy of Environmental Impact Statements in 1987.

A trail map from Culhane, Friesema. and Beecher field work studying Illinois Beach State Park.

What also emerged from this study was a newly processed archival collection housed in Northwestern University’s Transportation Library. The Paul J. Culhane and H. Paul Friesema NEPA Precision Research Project Collection contains the work of these researchers over the years it took for them to study the predictive accuracy of EIS’s. The five boxes of materials that comprise this collection contain a rich breadth and depth of materials waiting to be explored. View the finding aid online.

These archives contain in-depth research on dozens of sites where EISs were made and their corresponding projects carried out. Many of the documents contained in this collection are preliminary drafts of government reports. Anyone wanting to research State Highway 64 in Wisconsin for example, has a rich source of information on that project as a jumping off point, research that other scholars have already compiled for them.

Part of that research is very formal, such as government reports, and some is as informal as a local community organizer recounting their own relationship with the project. One strength of this collection is that you can find material from activists and community members surrounding these projects that might otherwise be difficult to find. The impact of EIS’s is not simply measured by the government’s point of view, but community work regarding projects, work that is in part held in this archive.

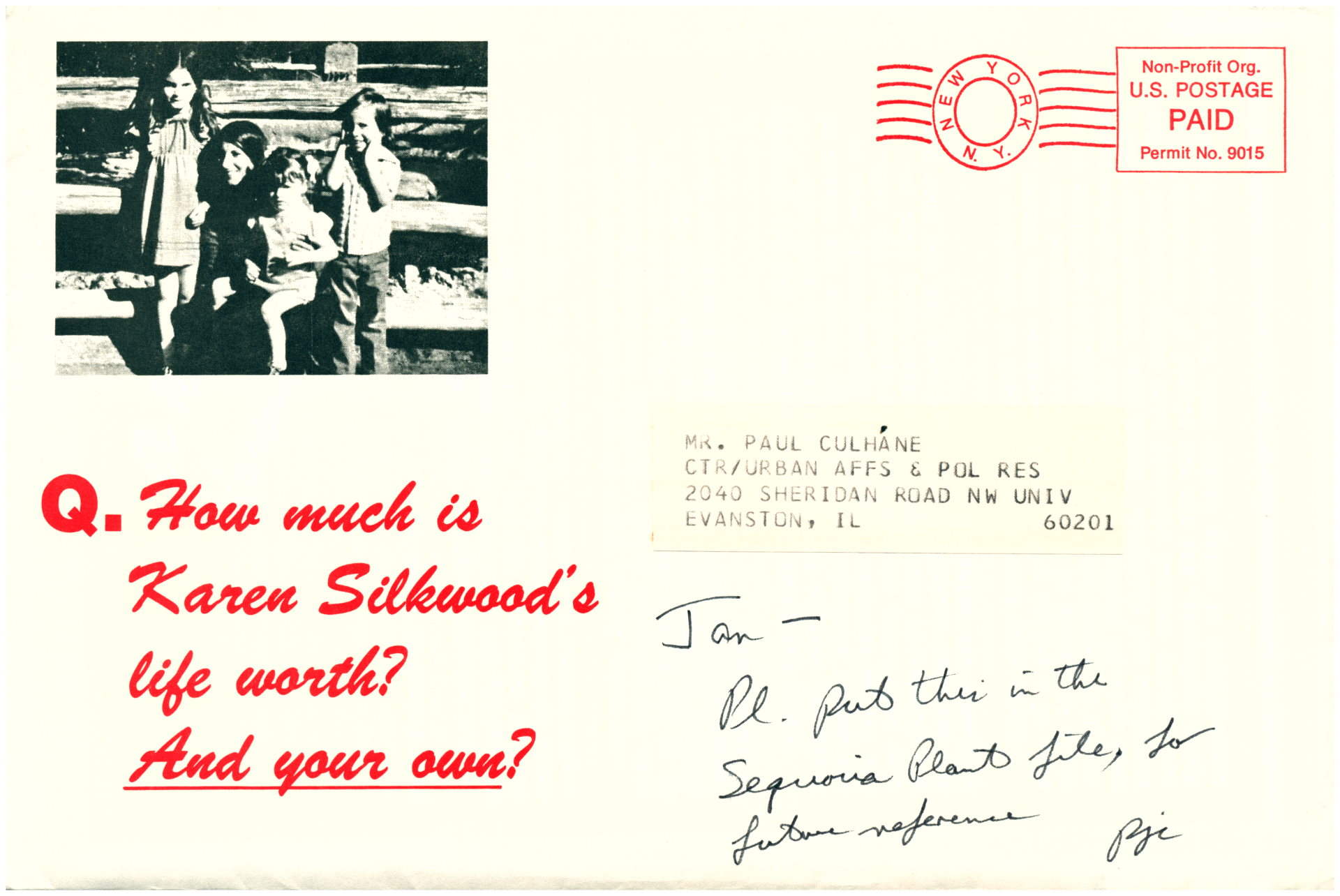

An example of community work is found sitting among Folder 14 in Box 2 of the collection—a folder stuffed to the brim with papers to the point that it is unwieldy to carry—is an envelope that reads “How much is Karen Silkwood’s life worth? And your own?” in bold, red text. Silkwood raised concerns about another Uranium processing plant owned by the same company in the same state as the one being studied. She was on her way to deliver documents about the plant to a reporter when her car crashed, killing her, with no documents to be found anywhere in the vehicle. This famous death and the long court battle that followed would capture national attention and result in a Hollywood film about the incident starring Meryl Streep .This folder contains a wide breadth of material on a plant very similar to the one Silkwood worked in. Researchers can see newspaper articles documenting accidents and deaths at the plant, hear from workers through interview notes, get the perspective of journalists, and understand the larger picture of the company Silkwood was involved with and the ways her death a decade earlier in a separate plant influenced the study of a wholly different location.

An envelope of materials on Karen Silkwood from the Christic Institute. Box 2 Folder 14.

Box 3, Folder 9 takes you through a political battle over a project in Warrenton, OR. What seems like an innocuous bridge replacement project turns into a battle between, in the words of the study’s authors, “local rabble raiser” Herb Palmberg and officials of the city government. The issue that caused such controversy in the town: a change in the span of the bridge that no longer allowed large boats to pass under it. An issue that even went to a local referendum, which you can see the results of in the folder. In reading this folder, you get to see a conflict between one man and a town council. You get to hear both sides of the story and see the results play out while you learn about Palmberg’s property, the fact that Palmberg wrote a letter about this small-town issue to President Reagan, and perspectives from those who agree with Palmberg and those who see him as a person in the minority working in his own self-interest. You get to hear two very different accounts of this project as well as the conclusion the study’s authors drew from it and get to take away from it what you want.

A sketch found on the back of a document in Box 5 Folder 3.

A pamphlet on pollution from Box 5 Folder 3 from the national park service.

Even without these more tangible benefits, there is a joy in watching the progress of these researchers as they work. There is a joy in seeing their interactions and thought processes, and a joy in discovering the small things in the collection. A map of hiking trails. A flier for river tubing. A person’s face sketched on the back of one of the documents with a pen.

One of the assets of this collection is the insight it offers into research methodology. You can track this study from its inception to its completion and gain insight into the steps taken to get from point A to point B. Not only do you get to see how decisions were made in the study, but you also get to follow how those decisions were carried out through correspondence, interviews, travel, and more. It offers an in depth look into how social science research is conducted, and possibly a point of comparison between the ways it was conducted forty years ago and how it is conducted today. There are also many documents containing printouts of old programming and code using now obscure social science research tools for anyone interested in the history of quantitative programming in the social sciences.

Whatever angle you approach looking this collection from, it’s undeniable that the study that emerged from it still has an impact even forty years out. Culhane, Friesema, and Beecher’s book was reprinted in 2019 and cited in academic articles as recently as this year. This collection also provides its users with an excellent opportunity to look further into the career of the three people who made it, who continued and do continue to make large impacts in their field.