For the past couple of years, Northwestern University Libraries has been working to digitize a large group of English-language titles printed before the year 1700 as a contribution to the EarlyPrint Library project. Here is a description of the EarlyPrint project from its website:

A collaborative effort—centered doubly at Northwestern University and Washington University in St. Louis—to transform the early English print record, from 1473 to the early 1700s, into a linguistically annotated and deeply searchable text corpus. […] The EarlyPrint Library aims to create a deduplicated digital library of most English books published before 1700.

165 unique titles at NUL were identified for the project. To ensure their safe digitization, the conservation lab surveyed the materials to assess their condition. Special attention was paid to the flexibility of the bindings since the digitization process requires books to open to 100° to capture the text.

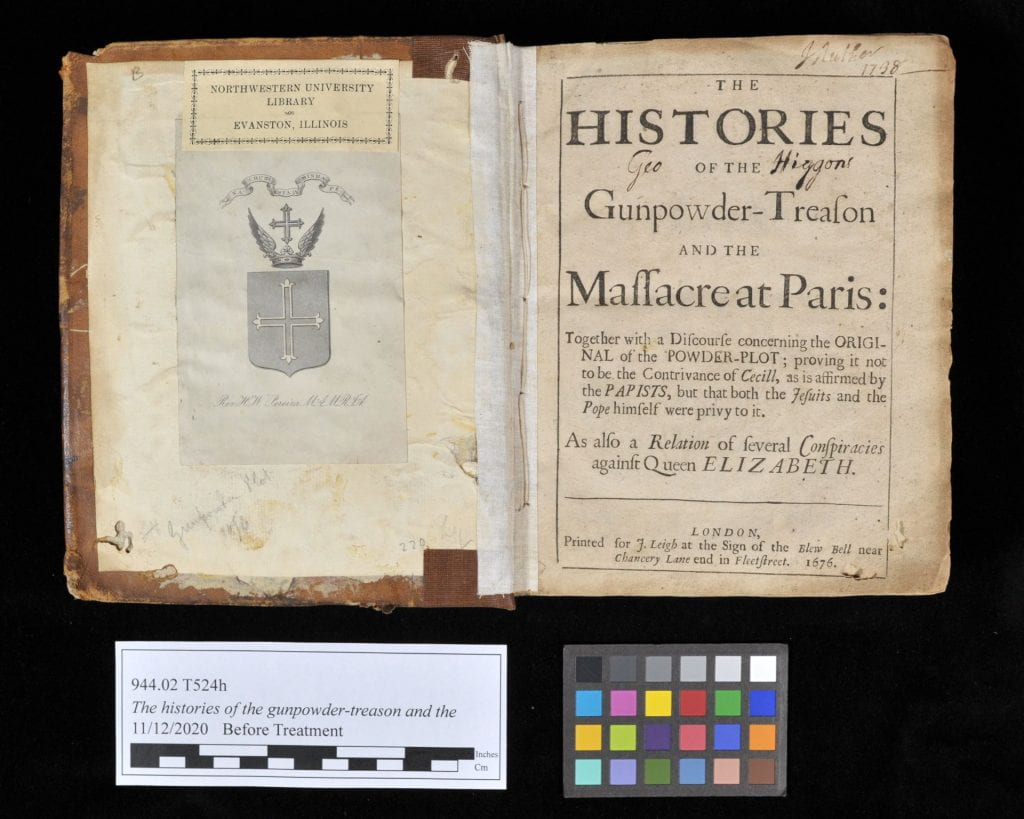

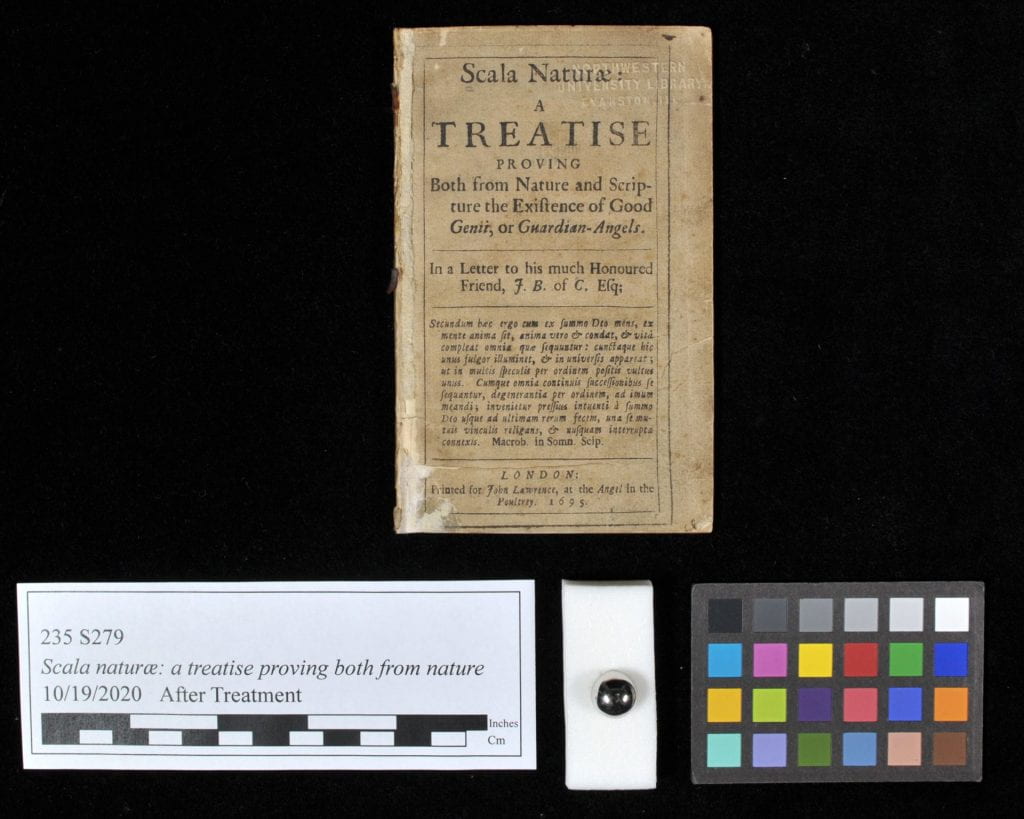

Some examples of the items digitized for the EarlyPrint project.

The materials designated for the EarlyPrint project range broadly in physical format, from single-leaf broadsheets to thick Sammelbände. There were quite a few texts still in bindings contemporary to their imprints. For these “original” bindings, we do our best to stabilize them while imparting as little change as possible.

Some EarlyPrint texts shown before and after treatment.

The survey showed that 65 of the items required treatment of some kind. While most of the texts needed only simple fixes like tear mending, there was a significant minority that called for more serious intervention. Several of the pamphlets in the group were bound into acidic paper wrappers with an excessive amount of hide glue, making them difficult to open. These were disassembled, washed (for more detail on washing paper, see our previous post on washing Soviet propaganda posters), and re-sized. And no, re-sizing does not mean we are changing the dimensions of the paper. The “sizing” is a coating added to the paper as a part of the original papermaking process. Conservators will occasionally apply a new sizing if the paper is weak or if there is a risk of washing away the original sizing during the soaking process.

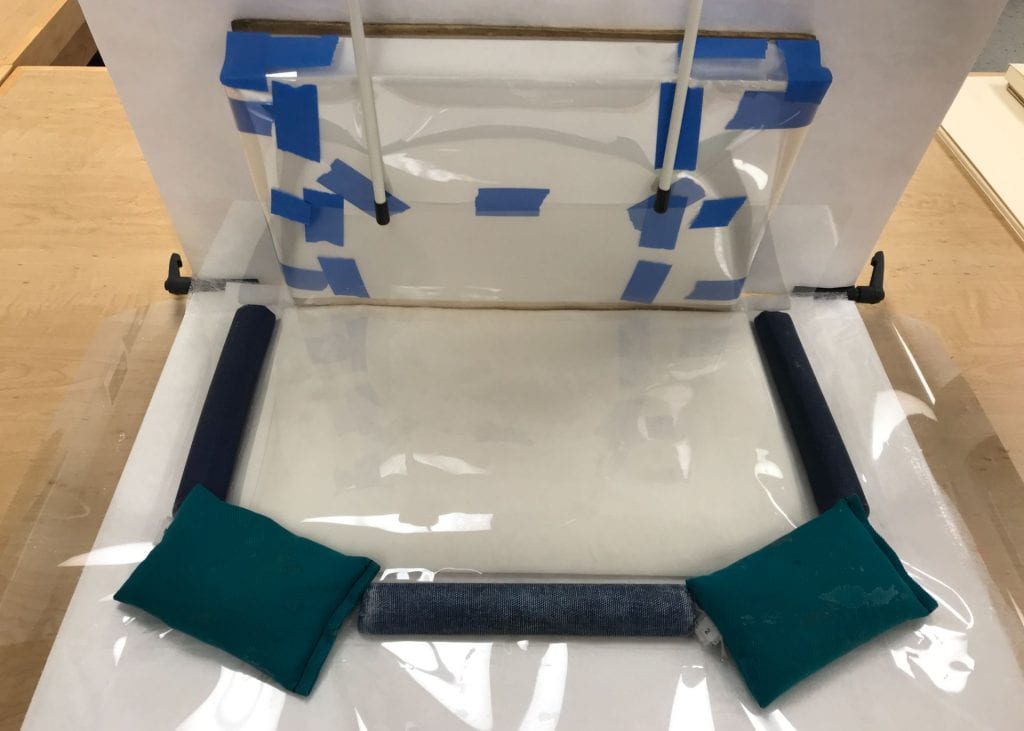

Washing and re-sizing pamphlets. This is a messy task that often requires multiple pairs of hands!

After the paper dried, the pamphlets were mended and re-sewn into new paper wrappers. Now they are more flexible and safer to handle.

Before and after washing, re-sizing, and re-sewing pamphlets.

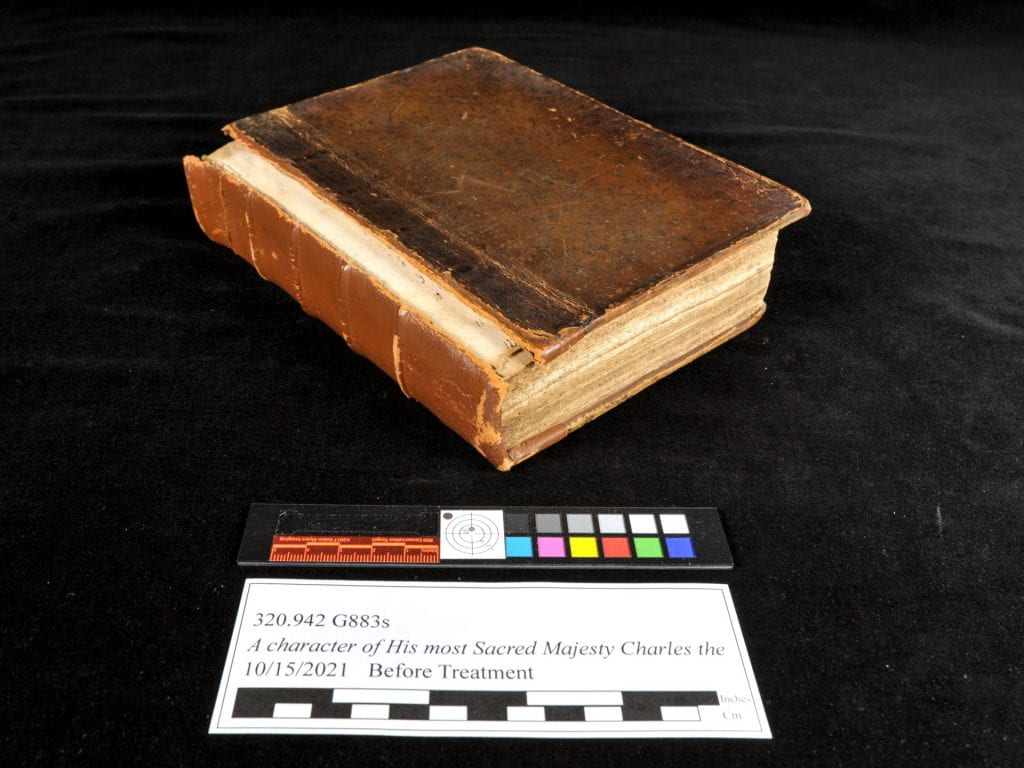

A few of the leather-bound books had heavily damaged spines and required “re-backing”—which is the term we use for replacing the spine material of a book. Re-backing can be one of the more challenging and time-consuming treatments for leather-bound books. Traditionally (and unsurprisingly) leather books are re-backed with new leather. But re-backs can also be performed with strong Japanese papers, coated with acrylic paints and wax to match the color and surface texture of the leather. If the original leather is still intact, it can be adhered over the paper re-back.

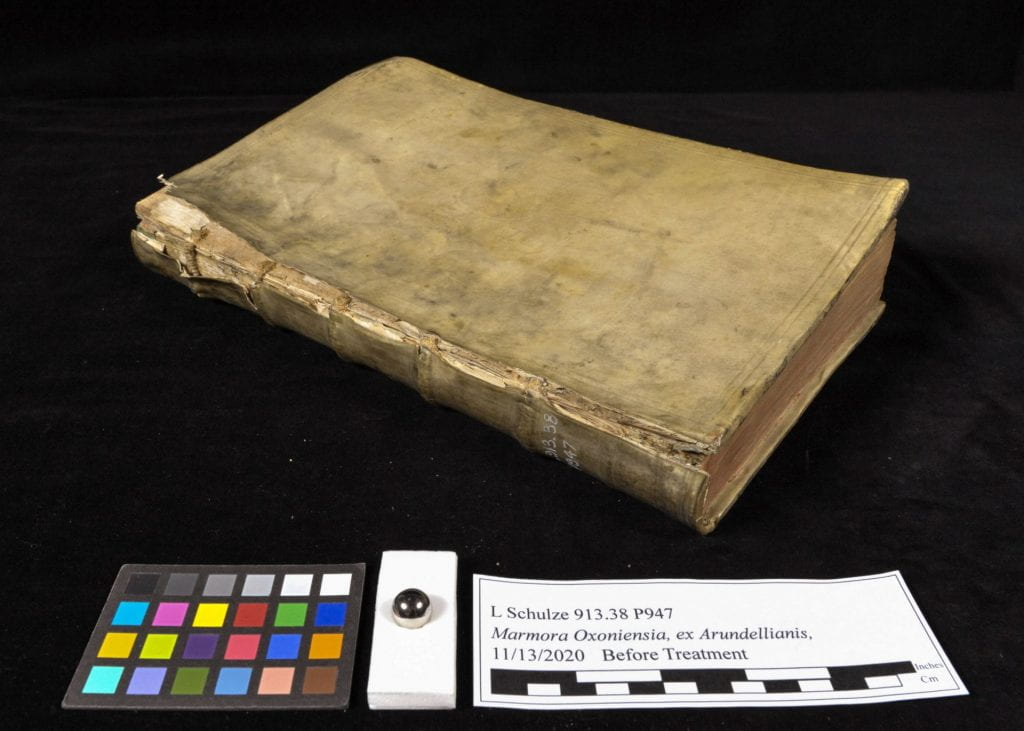

Before and after applying re-backs.

Conservation Resident Karissa Muratore put a leather re-back on one large binding (A Character of His Most Sacred Majesty Charles the Second, 1661). To allow the book to open better, she changed it from a tight-back structure (where the leather adheres directly to the spine) to a hollow-back, which allows the leather to pop away from the spine as the book opens. She dyed new archival calf leather to match the tone of the original leather and carefully pared it down to fit around the spine.

One of the books (Marmora Oxoniensia, 1676) is in a folio-size full-parchment binding. When it came to the lab, its boards were dramatically warped, and the parchment was split along the joint, revealing the binding’s structure underneath. Karissa gently humidified the boards and dried them under pressure for two months. She fixed the splitting board hinge with thread that was sewn around the original broken cords. Where possible, she avoided covering up the exposed binding structure. The book was placed in a box with a “pressure lid” to keep it from distorting in the future.

A couple of the EarlyPrint books were in such bad shape that they needed to be entirely rebound. Check out Karissa’s blog post about the binding structure she adapted to protect these texts and keep them flexible for digitization.

The EarlyPrint project has presented us with some interesting challenges and fun learning opportunities. All in all, the project has taken the conservation lab roughly 475 hours to complete. It isn’t often that we get to handle such a large group of texts from this era. We are pleased to contribute to such a fascinating and ambitious project!