Music Library head Don Roberts and composer John Cage in Deering Library, 1992

When Don Roberts became the second-ever head librarian for Northwestern’s Music Library in 1969, the library had a nuts-and-bolt mission: Provide whatever scores, records, and books the Music School required to support curriculum.

But by the time Roberts retired in 2002, the Music Library had been transformed into a renowned collection of contemporary music and archival collections worthy of a world-class research institution, said D.J. Hoek, the former head of the library who succeeded Roberts in 2004.

Roberts died on March 30 at the age of 83, leaving behind a legacy of grand vision, innovation, and mentorship that continues to have an impact at Northwestern and beyond. Hoek, the current Associate University Librarian for Research & Engagement, called Roberts’ career “a story of the Music Library becoming something more than just a functional collection to support curriculum.” Roberts’ tenure at Northwestern coincided with a period of extraordinary growth for the University, and for academia in general, Hoek said. And Roberts made the most of the moment.

In a 2021 interview with former School of Music Dean Bernie Dobroski for The Emeriti News, Roberts recalled University Librarian Tom Buckman pulling him aside, saying, “We want to make the music library a collection of distinction, on the same level as (the Herskovits Library of) Africana and (the Transportation Library)… Let’s really put the library on the map.”

So Roberts surveyed the music library landscape and tried to identify a need.

“Well, we can’t go out after manuscripts of the biggies, because basically they are not available,” Roberts recalled with Dobroski. “They’re already in institutions, or, when one arrives on the open market, the price is so prohibitive it would bankrupt the university.”

That’s how he arrived at the idea to collect music after World War II. “The reasons were several: One, nobody was collecting that period in sort of a systematic, comprehensive way. Two, it was basically in print, so therefore it was easy to get and therefore, three, quite inexpensive because you didn’t have to get into the antiquarian market.”

What Roberts proposed was a switch from a standard collection strategy — where librarians look at catalogs and make one-by-one selections — to a blanket plan that cast the broadest possible net for modern scores.

Essentially, “Don said, ‘Give us one of everything,’” Hoek said. “No other music libraries were doing something like that then.”

The strategy accelerated the Music Library’s collection exponentially and necessitated new methods for acquiring such a surge in scores. Then as now, many libraries acquired books in bulk via vendors such as the German company Harrassowitz that automatically acquired and shipped entire categories of new books according to a library’s specifications. These “approval plans” allowed libraries to save time and effort when they want to stay current in a specific field. At the time, though, that service did not exist for music scores. Roberts had to invent it — and since so much contemporary music was published in Europe, Harrassowitz made the perfect partner.

With Northwestern as its bellwether, Harrassowitz developed an approval plan system for scores, a successful service the company offers to many libraries to this day. But while most libraries still go through a huge list of composers one by one to do their selecting, Hoek said, the profile for Northwestern remains much the same to this day: “Every score from nearly every composer on the list, with nearly every possible instrumentation; we receive one of each.”

The collection strategy was bold because it didn’t just divert from the library’s curriculum-only model — it meant “we were acquiring music from composers we had never heard of,” Hoek said. “That was a real leap. But if their music was being published, Northwestern wanted to have it.”

That leap meant the University could call itself an authority on contemporary music, commensurate with that directive to build a “collection of distinction.” The result was a concentration of material worthy of study by the international research community, not just Northwestern. When the School of Music founded its Institute for New Music in 2012, a definitive contemporary collection already existed in support of it. At last, contemporary was the curriculum.

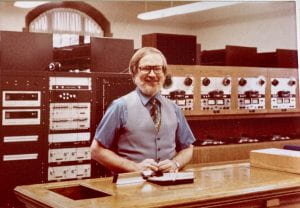

Roberts in the Music Library Listening Center, ca. 1976

Roberts didn’t stop there in his quest for a collection of distinction. Despite his concern that he couldn’t afford “the biggies” from the antiquarian market, he nonetheless pursued a more subtle course for acquiring unique primary source materials.

Hoek credits Roberts’ ability to forge cordial relationships with vendors and collectors of all types, so that when something became available on the market, people would think to call him.

Take the most important acquisition of Roberts’ career: the collections of John Cage, among the most influential composers of the 20th century — and certainly the most revolutionary. Roberts had let his vendors know that he was interested in making Northwestern a center for contemporary music; meanwhile one of those vendors was approached by Cage, who was looking for a place to deposit his papers. (A small apartment fire had jolted him into preserving his career materials.) Soon, Roberts got a call. A soft voice on the other end said, “This is John Cage.”

“I thought, okay, one of my friends is pulling a prank on me,” Roberts later recalled to Doboroski. “I couldn’t envision that John Cage would have a very small, gentle, almost meek voice like that.”

It was no prank, and soon Roberts was in New York to spend “a most enjoyable day” with Cage. He struck up a relationship that won the composer over.

“Don got to know Cage, and Cage trusted him,” Hoek said. Soon, Cage delivered his materials from the Notations project, his 1969 book that compiled scores from hundreds of experimental and traditional composers — scores as striking for their varied visual expressions as for the sounds they represent. Other works of Cage’s came too, such as his manuscript for Music of Changes, his first work to employ the divination methods of the I Ching to make compositional decisions. Also among his deposited papers: a set of seven handwritten lyric sheets by the Beatles, donated to him through correspondence with Yoko Ono.

Roberts asked if there was anything else Cage could deposit, and soon the composer sent a voluminous archive of past correspondence. He started keeping a box under his bed marked “Northwestern,” into which he poured his performance programs, books given to him, and a variety of materials others sent to him, all now catalogued as the “Cage ephemera.” When a box got full, he sent it to Roberts.

“Cage was such a major figure — an influential creative force, and connected to everybody,” Hoek said. “The acquisition of the Cage collection was pivotal for Northwestern, and it is still one of our most important and most used archives.”

Later acquisitions like the archive of musician and performance artist Charlotte Moorman and the papers of artist Dick Higgins were fueled by the catalyst of Cage, cementing Northwestern as a hub for the study of avant-garde and Fluxus art movements.

Not all acquisitions were of modern materials. Roberts worked with Doboroski, his contemporary, to acquire part of the Moldenhauer archive, an eclectic collection owned by a German musicologist, and comprising rare music manuscripts and other materials spanning 1683 to 1973. The acquisition faltered halfway through when Northwestern and the donor had a falling out, as Roberts later recollected — but nonetheless the Music Library ended up with important works and musical sketches from composers such as Ernst Bloch, Gustav Mahler and Camille Saint-Säens.

The papers of conductor Fritz Reiner also came to Northwestern early in Roberts’ tenure. Reiner, a longtime conductor of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, can now be studied at Northwestern through his scores dotted with performance markings and his correspondence with musicians and orchestras around the world.

The legacy of Roberts’ acquisition strategy continues to this day. Current Music Library curator Greg MacAyeal continues to seek rare materials that tell the story of modern musical experimentation. In 2019, he completed the acquisition of the archive of Glenn Branca, the avant-garde rock guitarist whose “noise rock” influenced later creators like Thurston Moore of Sonic Youth. MacAyeal also oversaw the acquisition of the Pat Patrick Collection of Sun Ra Materials, a set of sermons and writings of the experimental jazz musician collected by a longtime band member, and a yet-to-be-announced archive of papers belonging to another influential composer who specialized in sound manipulation and electronic music.

“These archives all inform each other; they all ask questions about what music is,” MacAyeal said. “The composers we’re collecting take a very broad approach to music and yet their archives show how their experimentation built on each other over time.”

As more pathbreaking composers continue to be archived at Northwestern, the Music Library will only further cement its stature as the most extensive research collection dedicated to contemporary music, he said.

As the collections grew under Roberts, so did the need for staff to manage the burgeoning library. Roberts didn’t just oversee a hiring surge at the Music Library, he earned a reputation as a mentor to his staff, and an influential proponent for the careers of many librarians and staff who worked with him. Vince McCoy, currently a technical support specialist with the Libraries, began his career in the Music Library as an 18-year-old work-study student. He maintained a lifelong friendship with Roberts, whom he called “a major influence on my life and career as both an NU student and a Library staff member.”

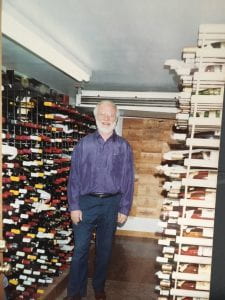

Roberts and his wife, Sally, were well known to colleagues for hosting parties and sharing their love of food and wine

“Don was my first mentor at Northwestern,” McCoy said. “He taught me everything I know about academic libraries. He instilled in me a service orientation that has served me well for my 46 years here.”

McCoy recalled how Roberts had assembled a “crackerjack crew of devoted and knowledgeable student employees” who perpetuated a culture of mentorship. McCoy called the staff his “siblings, and Don was our caring father.” Together they made the Music Library a hub of activity.

“Everyone dropped by the Music Library during the day,” he said. “You came to check out books or scores for class, but just as often you came to hang out with your friends. Don was building a community and a library.”

Yet another way Roberts supported and influenced others was through his service to several professional associations. He was especially active in the Music Library Association and the International Association of Music Libraries, Archives, and Documentation Centres, serving in a range of elected positions including as president of both organizations. Other organizations for which he held leadership or editorial roles included the Society for Ethnomusicology, the Association for Recorded Sound Collections, the Society for American Music, and the Recorded Anthology of American Music.

Speaking after Roberts’ death, Dobroski reflected on the privilege of serving as dean while Roberts was his library partner.

“He had the professional skills and pedagogical skills, and he was well liked,” Dobroski said. “He was the whole package for a music school and a music library.”