By Karissa Muratore

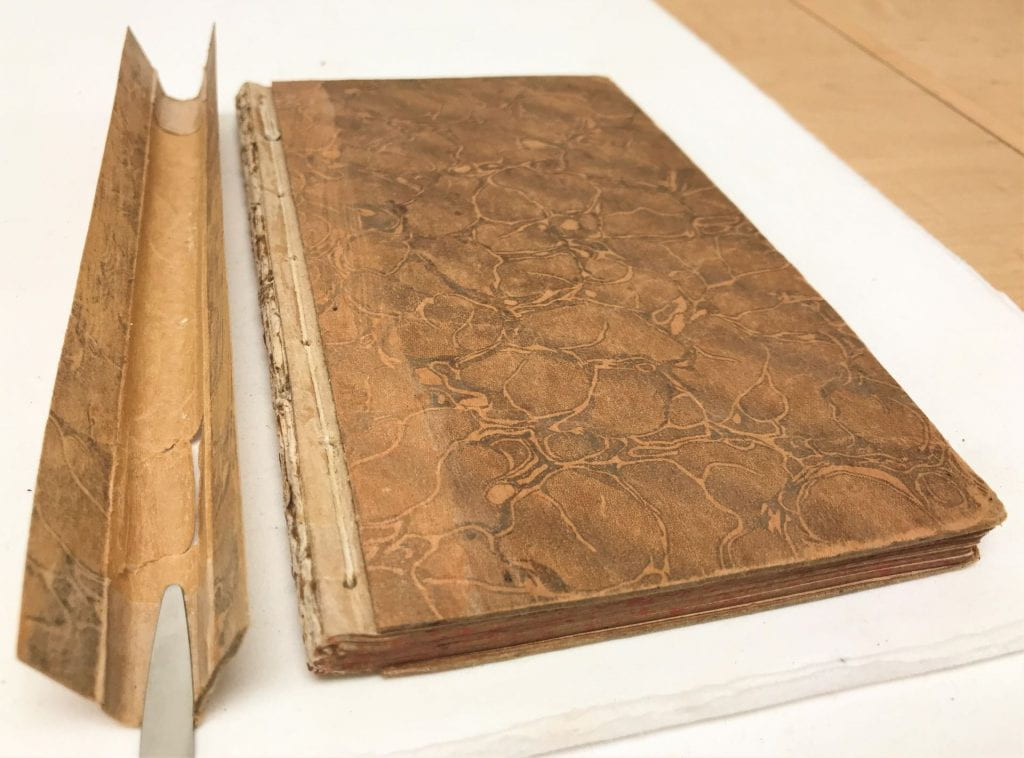

As the new Conservation Resident at Northwestern University Libraries, and after having spent the previous six or so months in quarantine due to COVID-19, I was eager to work with real objects, in a real lab, and with real people (at a respectable social distance of course). One of my first projects was a small book, published in 1699, entitled Moral Essays from NUL’s McCormick Library of Special Collections and University Archives. This book was in an acidic, non-original library binding. The side-sewn structure made it impossible to read, let alone digitize, as part of collaborative EarlyPrint digitization project with Washington University in St. Louis. After a consultation with the curator, it was decided a rebinding would be in the best for the book’s current and future preservation needs.

Fig. 3: Frost’s standard model diagram (Guild of Book Workers Journal, 2013, p.22)

Rather than make an educated guess at the original binding style, I felt a simple conservation binding would be the least invasive and time efficient option—protecting the textblock from further damage while also being easily reversible should a different binding be desired in the future. Roger Williams, NUL’s Book and Paper Conservator, suggested the sewn board binding—a structure first introduced to the book conservation community by Gary Frost in the late 1980’s. In Frosts words, while many other historical structures have been adapted for conservation rebinding practices, “the sewn board structure has not been actively drawn on in book conservation practice.”[1] Not knowing much about the structure and taking Frost’s words to heart, I did some research and made a model based off Frost’s standard model (see Fig. 3).[2]

I loved it! It is minimally invasive, structurally sound, has great opening mechanics, and is easy to aesthetically modify if you want to reference a certain time period. However, the break-away spine, a core feature of the structure, did not allow the book to truly open flat. If used, it would still need supports despite being quite small. While not a real problem, I wondered if the structure could safely open flat with some conservation modifications. After a few rounds of material testing and model making, I identified adaptions I believe to be advantageous for conservation binding, including a major change in the spine mechanics. I would like to note, my research into this structure is by no means exhaustive. As Frost says, “[b]ookbinders have such a rich resource of historical structures that any invention is likely to be a reinvention.”[3] This is a personal exploration into the adaptability of the sewn board structure for conservation.

I am not going to list step-by-step instructions and reasoning of Frost’s original structure here. If interested, you are better off reading one of his three publications on the structure, which are listed in the bibliography. In addition, Darryn Schneider has three very helpful YouTube videos demonstrating the original structure along with other variations on it. I am instead going to focus on the major adaptions I made, how they differ from Frost’s standard structure, and what effect they had on Moral Essays’ final structure mechanics.

Sewing

Frost’s standard model uses the link stich on paired sewing stations, [4] though he later mentions the chain stich as a conservation alternative.[5] I chose the chain stich as a conservation alternative for Moral Essays because it can be used on already existing sewing holes—avoiding the creation of unnecessary new holes. The unsupported, thread-only sewing, ultimately provided balanced tension, while lying fairly flush with the textblock.

Endpapers

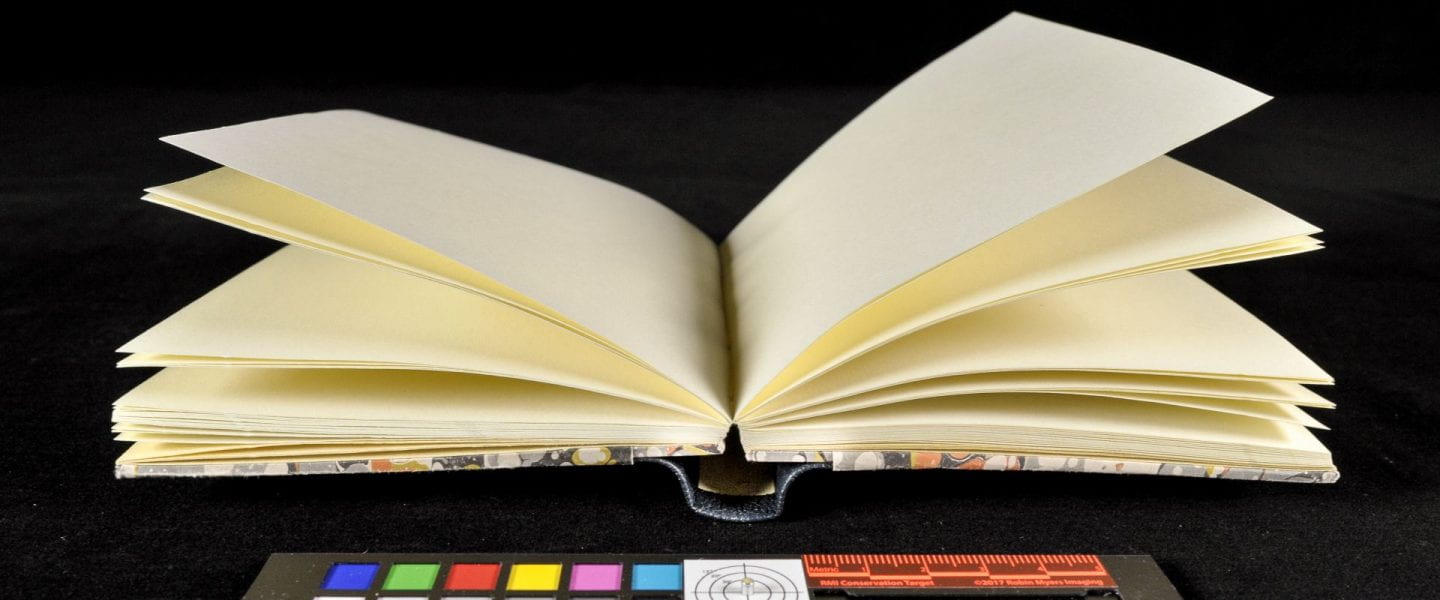

Fig. 8: Detail of sewn-in double folio endpapers, after treatment

Tipped, unsewn endpaper folios are used in Frost’s standard model. There are many ways to secure endpapers to a textblock and tipping-in is not uncommon. He chose this method to create a clean board opening. However, I did not want to unnecessarily attach anything to the original textblock if it could be avoided. I chose to simply sew in a double folio of a conservation quality laid paper that shared some characteristics with the textblock. By doing this, the endpapers seamlessly became part of the Sewn Board structure, with one leaf functioning as the pastedown and the others acting as protection for the textblock.

Fig. 9: Detail of board filler, with negative space to accommodate sewing.

Boards

The boards are made out of a folio card material. I used 10-point folder stock. An adjustment I learned from Darryn Schneider[6] is to remove a sliver of the board filler’s spine edge, from kettle stitch to kettle stich. This small negative space accommodates the sewing and allows you to set the filler board snuggly into the fold of the folio card. Another trick that helps with getting a snug fit is to fold your folio card around your uncut filler board before sewing. This way the folio card will later conform perfectly to the filler board. Frost mentions that this and additional filler boards on the covers can be shaped to help accommodate swelling or textblocks that already have strong shoulders.[7] This is an intriguing adaption, but this textblock did not have shoulders or enough swelling to warrant it; due to the changes I made to the spine, I did not need an outer filler card. In addition, I used Lascaux 498 instead of PVA as my adhesive. Lascaux does not have the same off-gassing issues as PVA does, and since such small amounts of it are necessary, using PVA didn’t seem like a necessary cost saving measure.

Fig. 10: Detail of inlaid linen to cover board edges that would otherwise remain uncovered.

Due to the nature of the covering method, the board edges near the spine will remain naked. This is only an aesthetic issue, but should it be considered distracting they can be toned, covered with toned tissue, or wrapped in one of the covering materials before attaching the spine covering material. However, depending on the materials being used, wrapping the board edges can cause bulk on both the exterior and interior of the boards. This additional bulk can be compensated for on the interior by using a spacer while sewing. The exterior bulk can be ignored or filler can be used along the length of spine edge of the board for a more seamless look. Another option, which I chose, is to inlay the same linen I was using on the spine by cutting away part of the folder stock. The lab’s linen happened to be the same width as the 10-point folder stock—conveniently creating a flush surface, to which I could later attach the spine overing material.

Fig. 11: ¾ back detail of Moral Essays, with small squares

Trimming

Newly-made book structures may have to be guillotined or hand plowed edges, but that is not acceptable for conservation. Part of the reasoning for this tactic is to avoid squares, so the textblock is not at risk of sagging when shelved upright. This is very unlikely for such a small textblock, especially since it has the additional support of a custom four flap enclosure. I also felt squares were necessary to ensure that the irregular textblock was protected, but I kept them very small to mitigate any potential sagging—2-3 mm. I also found to ensure correctly sized boards and endsheets, it is best to determine and cut the height of all the binding materials first while leaving the width a little longer than necessary for later trimming. If including a small square, you must make sure to correctly punch the sewing holes into the folio card boards. Using a jig is helpful for this whether you are using original or new sewing holes.

Spine Covering Material and Attachment

Fig. 12: Example of interchangeable test covers for conservation model showing textile spine lined with Asian paper, no spine stiffener, and continuous fold at head and tail.

After experimenting with multiple interchangeable test covers, I selected a variation that altered the spine covering so it is more flexible and fit snuggly next to the textblock spine without breaking away. The spine covering can be any material, but I ended up preferring the lab’s linen for its strength, flexibility, and neutral aesthetics. I also found that lining the textile with an Asian paper made the textile easier to cut and align on the book (provided a soft surface that could safely contact the textblock’s spine) and helped the textile retain its shape. Since the spine does not break away there is no need for a spine stiffener. Part of the spine stiffener’s job is to help give a hint of endcaps, but this can still be done with the textile alone in the same manner if desired. The thickness of spine material and its lining will likely depend on book size—the smaller the book the thinner the materials can be. I also found that retaining the continuous fold of the new spine covering material in Frost’s model vs. changing it into traditional turn-ins, in combination with a paper lining, helps create the right balance of stiffness and flexibility. It allows the textile spine to conform to the textblock’s spine when open while also maintaining a durable endcap when closed. To achieve this, the spine material needs to be adhered all the way to the spine edge of the boards, which is different from Frost’s model that is only partially adhered. This change—in overall spine material and attachment—inverts the mechanic; instead of the spine material popping out, it pops in. It conforms to the textblock spine when both open and closed and without being directly adhered to it, which offers better reversibility.

Fig. 13: Detail of Morals Essays opening mechanics after treatment

In conclusion, I agree with Frost that “book conservators readapt historical structures to modern methods and modern problems [and that] the sewn board family of bookbinding structures is equally timeless and renewable today,”[8] thus it has great potential if we take the time to realize its advantages and experiment with its design. These are just some of the adaptions I made, and I look forward to the creative adaptions of others.

References:

Frost, Gary. “The Sewn Boards Binding.” DAS Bookbinding WordPress file. Accessed March 9th, 2021. https://dasbookbinding.files.wordpress.com/2020/06/garyfrost-sewnboardsbinding.pdf

Frost, Gary. 2013. “Sewn Board Bookbinding; More than a Thousand Years Later.” Guild of Book Workers Journal 2010-2011: 18-26. Accessed March 9th, 2021. https://guildofbookworkers.org/sites/guildofbookworkers.org/files/journal/gbwjournal_2010-11.pdf

Frost, Gary. 2004. “Application of Sewn Board Technique to Book Conservation Practice.” The Book and Paper Group Annual 23: 33-39. Accessed March 9th, 2021. https://cool.culturalheritage.org/coolaic/sg/bpg/annual/v23/bpga23-06.pdf.

Hanmer, Karen. 2013. “Variations on the Drum Leaf and Sewn Boards Bindings.” Guild of Book Workers Seminar on Standards of Excellence in Hand Bookbinding October 26, 2013. Accessed March 9th, 2021. Microsoft Word – FINAL_SB_DL_GBW_2113_handout.docx (guildofbookworkers.org)

Hébert, Henry. “Sewn Board Bindings.” Work of the Hand Blog. Accessed March 9th, 2021. Sewn Board Bindings – Work of the Hand (henryhebert.net)

Schneider, Darryn. 2020. “Sewn Board Binding Part 1 – Adventures in Bookbinding.” DAS Bookbinding. Accessed March 9th, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7u1rFKnTC08

Schneider, Darryn. 2020. “Sewn Board Binding Part 2 – Adventures in Bookbinding.” DAS Bookbinding. Accessed March 9th, 2021.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ccCNqqNMstQ

Schneider, Darryn. 2020. “Sewn Board Binding Part 3 – Adventures in Bookbinding.” DAS Bookbinding. Accessed March 9th, 2021.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aDc5EFWErro

[1] Frost, Gary, 2013. “Sewn Board Bookbinding; More than a Thousand Years Later.” Guild of Book Workers Journal 2010-201: 24. Accessed March 6th, 2021. https://guildofbookworkers.org/sites/…

[2] Frost, Gary, 2013. “Sewn Board Bookbinding; More than a Thousand Years Later.” Guild of Book Workers Journal 2010-201: 22. Accessed March 6th, 2021. https://guildofbookworkers.org/sites/…

[3] Frost, Gary, 2013. “Sewn Board Bookbinding; More than a Thousand Years Later.” Guild of Book Workers Journal 2010-201: 25. Accessed March 6th, 2021. https://guildofbookworkers.org/sites/…

[4] Frost, Gary, 2013. “Sewn Board Bookbinding; More than a Thousand Years Later.” Guild of Book Workers Journal 2010-201: 22. Accessed March 6th, 2021. https://guildofbookworkers.org/sites/…

[5] Frost, Gary, 2013. “Sewn Board Bookbinding; More than a Thousand Years Later.” Guild of Book Workers Journal 2010-201: 25. Accessed March 6th, 2021. https://guildofbookworkers.org/sites/…

[6] Darryn Schneider DAS Bookbinding. 2020. Sewn Board Binding Part 1 // Adventures in Bookbinding https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7u1rFKnTC08

[7] Frost, Gary, 2013. “Sewn Board Bookbinding; More than a Thousand Years Later.” Guild of Book Workers Journal 2010-201: 25. Accessed March 6th, 2021. https://guildofbookworkers.org/sites/…

[8] Frost, Gary, 2013. “Sewn Board Bookbinding; More than a Thousand Years Later.” Guild of Book Workers Journal 2010-201: 26. Accessed March 6th, 2021. https://guildofbookworkers.org/sites/…