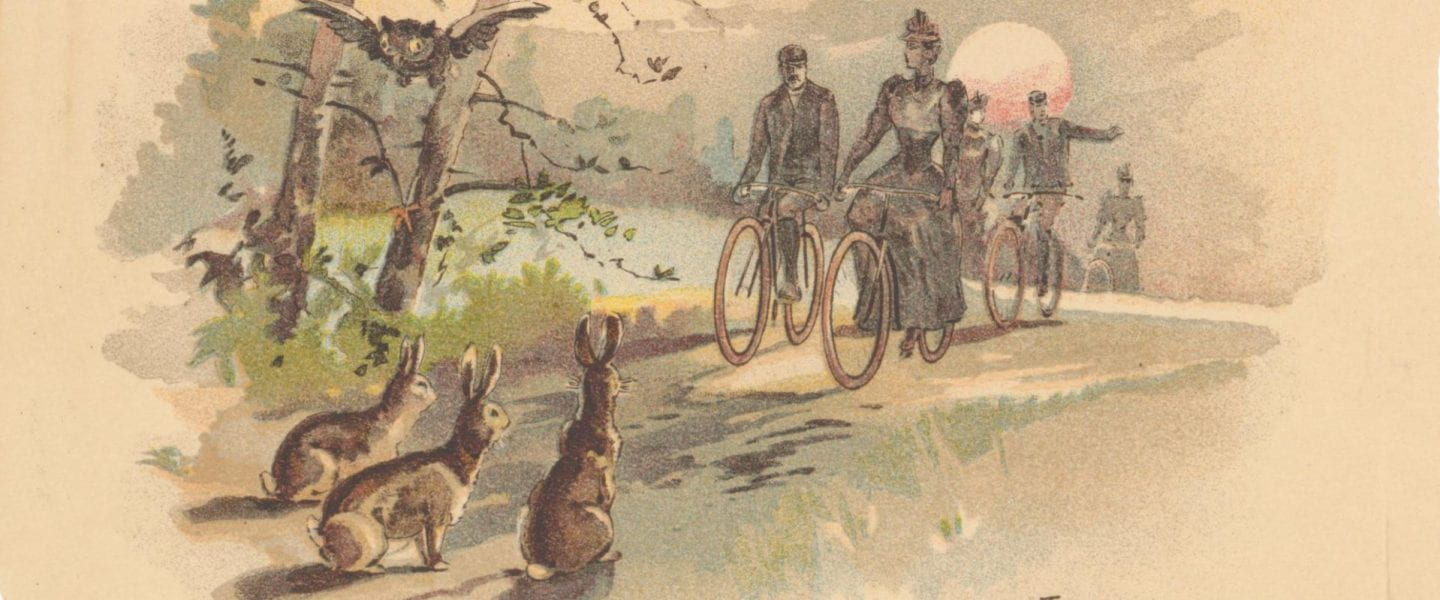

The safety bicycle was introduced in the 1880s, an alternative to the high-wheeler, or “ordinary” bicycles that had previously dominated the market. Improvements in safety and the invention of smoother-riding pneumatic tires contributed to the widespread public adoption of bicycles. Out of the bicycle boom that followed in the 1890s came numerous new manufacturers, along with intense competition between these manufacturers, who produced beautifully designed catalogs promoting the bicycle as a form of transportation, recreation, amusement, and a creator of community and freedom of mobility.

The Late 19th – Early 20th Century Bicycle and Bicycle Parts Catalogs Collection comprises 71 of those catalogs, dating from 1890 to 1932. Held in the collections of Northwestern University’s Transportation Library, these catalogs have been digitized and are now fully available to the public in our Digital Collections portal.

The Chicago area was a hub of bicycle manufacturing during this period; at one time, eighty-eight local companies produced nearly two-thirds of the nation’s bicycles, according to WTTW’s History of Biking in Chicago. That our region was so closely aligned with bicycle transportation during this period guided the Transportation Library’s early approach to building this collection, which initially focused on Chicago-area manufacturers, and which was built, in the beginning, one catalog at a time. The collection has grown since then, and has expanded to include catalogs representing manufacturers outside of Chicago, including locations across the Midwest and East Coast.

A selection from the collection appears below. Users can click through the images to see each catalog in its entirety.

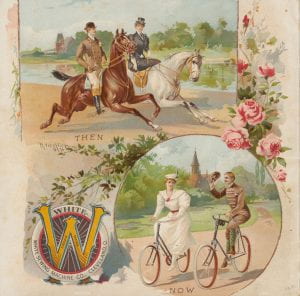

The popularity of cycling in the 1890s was so great, and the demand for bicycles so high, that companies like the White Sewing Machine Company of Cleveland, Ohio shifted production to bicycles. The company’s 1896 catalog featured White bicycles in illustrations depicting “then and Now” scenes of mail delivery, family outings, and rides through Central Park as they would have appeared before the bicycle age, and, it is imagined, with greater enjoyment and ease with the bicycle.

One illustration shows a woman in a long dress, bent over a spinning wheel and hard at work on “the wheel of the past,” contrasted with “the wheel of the present” – a woman dressed in bloomers, kicking out a leg behind her bicycle in a display of the freedom that cycling – and women’s cycling apparel – encouraged during this period.

One illustration shows a woman in a long dress, bent over a spinning wheel and hard at work on “the wheel of the past,” contrasted with “the wheel of the present” – a woman dressed in bloomers, kicking out a leg behind her bicycle in a display of the freedom that cycling – and women’s cycling apparel – encouraged during this period.

Indeed, Crawford Manufacturing Company devoted a catalog to The Modern Spinning Wheel, which allowed women to break out of the “narrow sphere of physical enjoyments” to which they had been previously resigned, and “take exhilarating rides across the country” on a Crawford.

As the decade went on and manufacturing techniques improved, bicycles, which at one time had been a luxury item, became more accessible to the masses. The William Wrigley Jr. & Co. Wrigley and Kinzie models sold for $27 and $19 respectively: “a strictly high-grade Bicycle at a price never attempted by anyone in the Bicycle business.”

Chicago was a major manufacturer of bicycles during this era. Western Wheel Works, whose factory occupied an entire city block on Chicago’s north side, published an 1896 catalog for its Crescent bicycles showing cyclists riding through locations in Chicago, New York, and New Jersey. Artesian Well in Chicago’s Lincoln Park was noted as a “famous resting spot for wheelmen.”

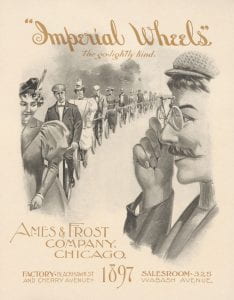

Another Chicago manufacturer, Ames & Frost, in its 1897 catalog, boasted of a large factory with 5.5 acres of floor space at Blackhawk & Cherry Avenues on Chicago’s Goose Island.

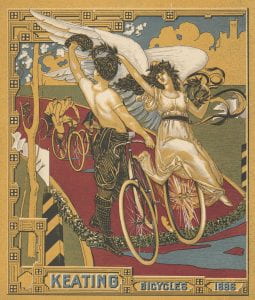

By mid-decade, the bicycle was no longer a novelty; in its 1896 catalog, Keating Wheel Company predicted the staying power of the bicycle and noted its many benefits: “The bicycle can no longer be looked upon as an oddity, fad, or luxury. It is one of the many 19th century inventions that fill a clearly-defined want – in fact if may be said to fill the wants of all, for it is a supporter of health, a promoter of pleasure, and a universally recognized business aid.”

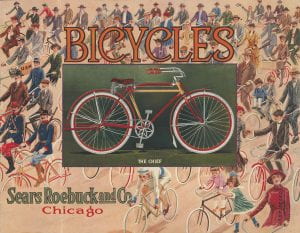

Cycling remained primarily an activity for adults through this early period, although some manufacturers did include children’s bicycles in their catalogs. In its 1909 catalog, Sears Roebuck & Co. includes inexpensive children’s models such as the Billy Boy Bike for as little as $4.95. The cover shows a crowd of cyclists including a mail delivery person, children, soldiers, bike racers, and what appears to be a baseball player, indicating an attempt at a broad public appeal.

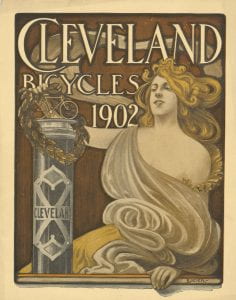

Even as demand and production began to decline after 1900, some companies continued to invest in catalogs that were beautiful examples of Art Nouveau illustration, including the Cleveland Bicycles catalog shown here. “We may say here that while many makers of bicycles have recently found it desirable to reduce their producing facilities, the CLEVELAND FACTORY at Westfield, Mass. has been enlarged one half during the past year.”

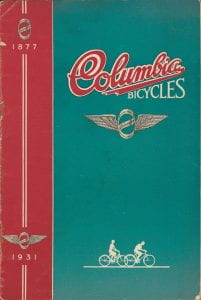

Although many companies folded as the demand for bicycles decreased with the beginnings of the automobile age in the early years of the 1900s, others persisted. This includes Columbia Bicycles, which listed illustrations in color of roadster, racing, and motobike (today known as cruiser) models designed for men, women, and children in its 1931 catalog.

This post represents only a small portion of the Transportation Library’s collection of bicycle catalogs. Please visit our Digital Collections repository to browse the collection online in its entirety, or the library’s catalog to learn more about our collections. There is also additional information on bicycle research in our bicycling research guide.

For more information on this collection, or on the Transportation Library’s services or collections, please visit our website or contact us at transportationlibrary@northwestern.edu. You can also find us on Instagram and Twitter.