By Jason Nargis, Special Collections Librarian for Instruction & Curriculum

One of my favorite times of the academic year is toward the end of each quarter when I communicate with faculty about planning for the upcoming class cycle. I love the process of curating the materials and learning outcomes for each unique syllabus.

At the end of February, English Department Artist in Residence and Instructor Eula Biss contacted me about hosting a visit to Special Collections & Archives for her English 498 class. I was thrilled to schedule this session and started to plan what I would share with her students.

Over the last several years, I have done numerous Special Collections presentations for Biss’s creative non-fiction classes. Biss is an award-winning author, with an ability to seamlessly blend detailed facts into dynamic and engaging storytelling, and has a great appreciation for the nuances of primary source research and the value of archivists and librarians. The learning goals have been to expose the students to archival research, to spark curiosity and wonder, and to perhaps provide some inspiration as a prompt for writing projects.

While I normally work to move beyond “show & tell” style class presentations in favor of a more active learning pedagogy, in this case the teacher has specifically requested wide-ranging overviews that highlight items with a unique resonance or viewer impact. This approach is reminiscent of the “cabinet of curiosities” that were assembled in Europe starting in the 16th century. These were hodge-podge collections of items including preserved animal specimens, geological samples, historical relics, anthropological artifacts, and more. These precursors to museums conveyed a breadth of scientific and cultural knowledge, as well as demonstrating the influence and authority of their owners.

I have tried to strike a balance between this “cool stuff” model that relies upon the aura of cultural significance and the awe of antiquity, with a critical studies sensibility that questions the powers and processes that establish the authenticity and import of the materials. I want students to be impressed by the beauty and influence of the items, while also learning to interrogate the politics of their prestige and presentation.

My usual entry point for this kind of instruction is material culture, or a kind of archeology of the artifact, through which physical evidence can be used to demonstrate the creation, use, and interpretation of the collection examples. Typeface choices, re-bindings, marginalia, and the smudges of repeated usage can convey how a book and its ideas impact and are impacted by societies through time.

And so we come to my dilemma: how do I convey the physicality of objects and primary source literacy in a distance-learning environment? While we are beginning more organized digitization projects, the vast majority of our collections are not digitized, and even if they were, the students are still lacking the ability to meet and touch and smell the artifacts. There are many people from across the Northwestern community dealing with some version of this screen-teaching dilemma right now.

As I looked for items to include in the class, I had to deal with the fact that very little of our collection material has been digitized. Northwestern is not alone in this; despite the tremendous reach of the Internet and the seeming omniscience of certain search engines, the vast majority of the world’s special collections and archives do not exist in electronic form.

We have some ambitious repository projects underway (see our ever-growing Digital Collections portal), and there are occasional files I could access from past scanning requests, but there was not much to choose from, especially scans done with enough resolution to make out some of the finer details of the artifacts.

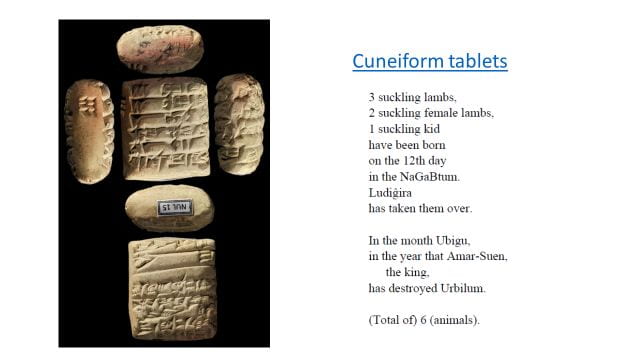

With a little creativity and searching, I was able to put together a meaningful selection of items. Since I was teaching for a writing course, I wanted to start with the oldest writing in our library: a group of Mesopotamian clay tablets written in cuneiform that are around 4,000 years old. Several years ago, Northwestern had collaborated with the Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative, allowing our 17 tablets to be scanned for open scholarship. Surprisingly, the detail of markings on the tablets is actually more visible in the digital image than in-person.

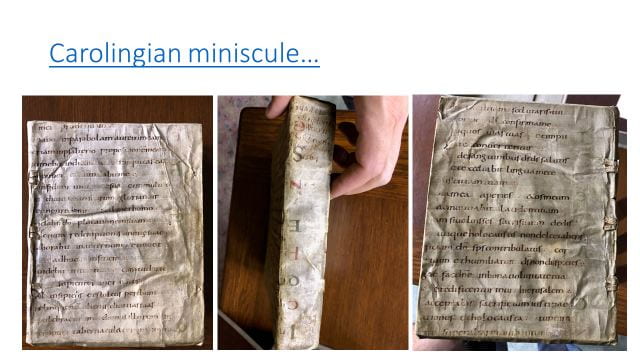

Binding waste parchment leaf from manuscript bible. Portions of two psalms written in Carolingian minuscule hand. c.825 C.E. (Presentation slide)

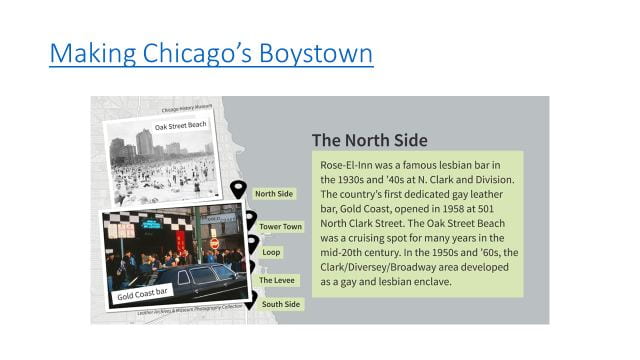

I also used images of items that had been shared on the McCormick Library’s Instagram page (@mccormicklibrary), including a parchment-waste binding with early 9th century Carolingian miniscule writing, and a manuscript written by the Italian Renaissance scribe Bartolomeo Sanvito. Another source were two online projects I collaborated on outside of the university: a digital exhibit on the history of protest in the Chicagoland area with Chicago Collections Consortium, and digital companion piece for several radio stories created with WBEZ’s program, “Curious City.” In addition to being able to see some of our collection material, these formats also presented some diverse storytelling structures such as situating artifacts in geographical space using maps, and contextualizing material in history using a timeline.

“Place of Protest,” online exhibit, in collaboration with Chicago Collections Consortium. (Presentation slide)

“Making Chicago’s Boystown,” digital project in partnership with WBEZ’s Curious City program. (Presentation slide)

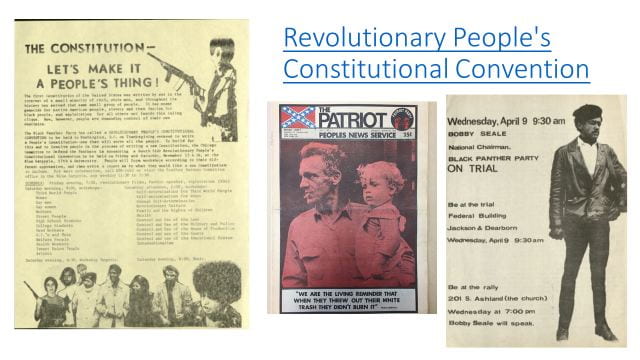

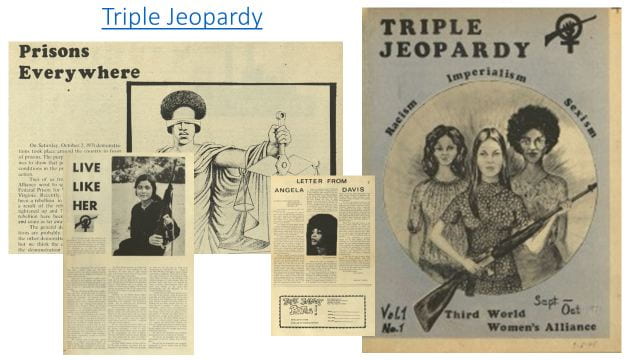

Over the winter quarter, I was an embedded librarian in Professor Amy Partridge’s first-year seminar on the coalitional politics between radical groups in the Chicago in the early 1970s. Every class session used a blend of digitized and physical primary sources from the McCormick Library. As a result I had access to a large trove of digital files from this rich collecting area. I chose to share some scans relating to the Revolutionary People’s Constitutional Convention, an attempt by members of the black power, feminist, and gay liberation (and other) movements to create a more equitable national constitution. Our copies of the newspaper Triple Jeopardy, an early proponent of the importance of addressing intersectionality in protest movements, was previously scanned for inclusion in an open-access project for alternative press publications called Independent Voices.

Publication and broadsides relating to the Revolutionary People’s Constitutional Convention, 1970 (Presentation slide)

Triple Jeopardy newspaper covering issues of “Racism, Imperialism, and Sexism.” 1971-1975. (Presentation slide)

I used several examples of material from other institutions as stand-ins for our own holdings. While we do not have scans of our nearly-400 posters from the 1968 student uprising and wildcat strike, the Bibliothèque Nationale de France has many available online. And although I could not display our copy of the 1493 Nuremberg Chronicle, the University of Cambridge has a beautiful scan of one of theirs in sufficient detail to see the ink squash (the raised ridge of ink around the outer edge of letterpress printed characters). The ability to access, and compare in the same screen, various editions of the same work from repositories around the world is something that would almost never be possible with physical items.

While I did a lot of talking at the start of the presentation, I tried to pose ripe questions and to highlight elements of institutional and intellectual complexity. The online examples I selected contained enough fine detail and metadata for meaningful literacy instruction. I also left plenty of time for conversation and questions, and I arranged for individual consultations with several of the students. All in all, I felt the session was successful, and Biss agreed.

“I wanted to introduce my writing students to the kinds of materials held in special collections — particularly objects, images, and artifacts — while also encouraging them to engage in exploratory, open-ended research,” she said. Though the library was closed, she felt we had “devised a truly exciting virtual tour of digital materials that ranged across many areas of interest while also offering a brief history of print. This ‘cabinet of curiosities’ left us all intrigued, as I hoped it would, and primed to explore the poetic possibilities of the materials.”

Regardless of how long the current distance teaching/learning circumstances go on, access to digitized, primary sources will continue to grow in importance to libraries and higher education. While virtual surrogates can never completely replace physical artifacts, there is a lot of substantive work that can be done with high-quality images, and the pedagogical lessons learned during these difficult times will help us all become better students, scholars, and educators going forward.