“On the Same Terms” is an exhibition and blog series dedicated to this academic year’s commemoration of the 150-year anniversary of the admission of women to Northwestern.

The most pressing question when Northwestern’s Board of Trustees resolved to admit women in 1869 was not how to educate them but how to supervise them. Trustees had concerns about women’s living arrangements, and who would maintain propriety and safety so that, as President Erastus O. Haven stated, “the inconvenience and evils which many dread may be avoided.”

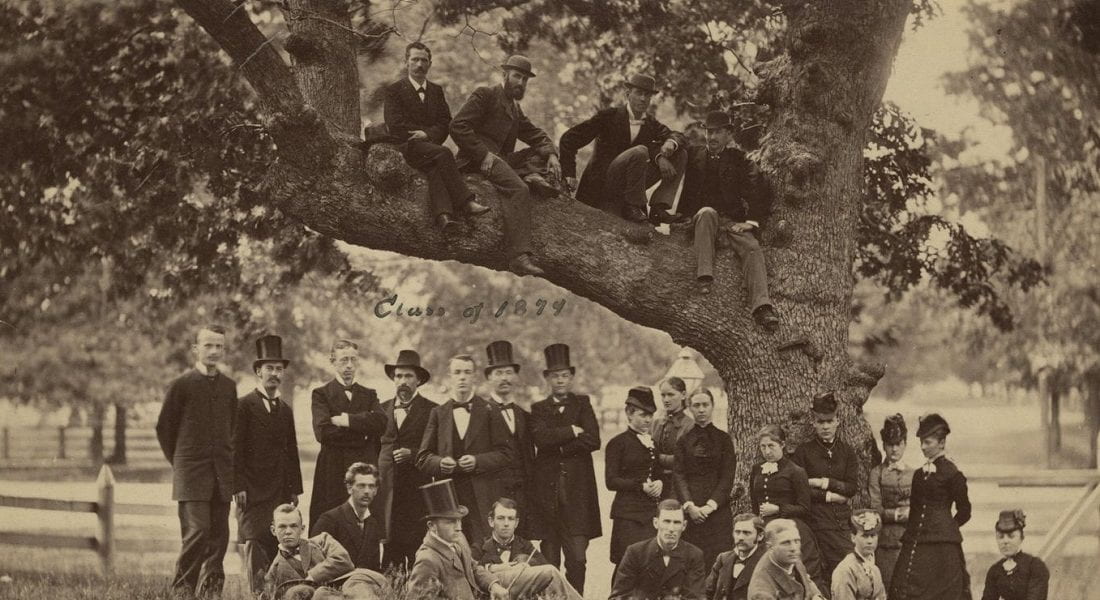

At the time, the student body totaled about 100. It would be many years before a dean of students or a student affairs department would be established, so the oversight of student life was the responsibility of faculty members. Northwestern’s all-male faculty was happy to cede the responsibility for women students to the dean of women (a position established in 1873, many years before a dean of men was appointed).

Northwestern’s first dean of women, Frances Willard, implemented the Self-Report, an honor system intended to teach women students to take responsibility for their own actions. The Self-Report caused a controversy that resulted in Willard’s resignation.

The assumption that rules and expectations for women and men needed to be different, that women required special protections and consideration, persisted well into the 20th century. And to a great extent, support for the concept’s long life came from women students themselves. This essay looks at the ways Northwestern’s women students took charge of their lives on campus, yet still reinforced societal norms and stereotypes.

Self-Government Organizations

As at other schools, Northwestern’s women students formed their own governance organizations, for a number of reasons, including solidarity, appeasing parents, and maintaining respectability. The formation of self-governance structures at colleges across the country—and the eventual establishment of a national women’s self-government association—indicate how similar was the experience of women in a coeducational setting.

Self-governance gave women students a degree of control over the issues that affected them, while also giving them leadership experience. Still, the issues mainly related to behavior, dress, hours, and permissions to leave campus—the same “in loco parentis” questions that had most concerned the Board of Trustees in 1869, and which continued to differ from men’s concerns.

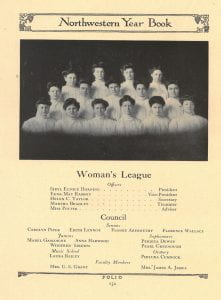

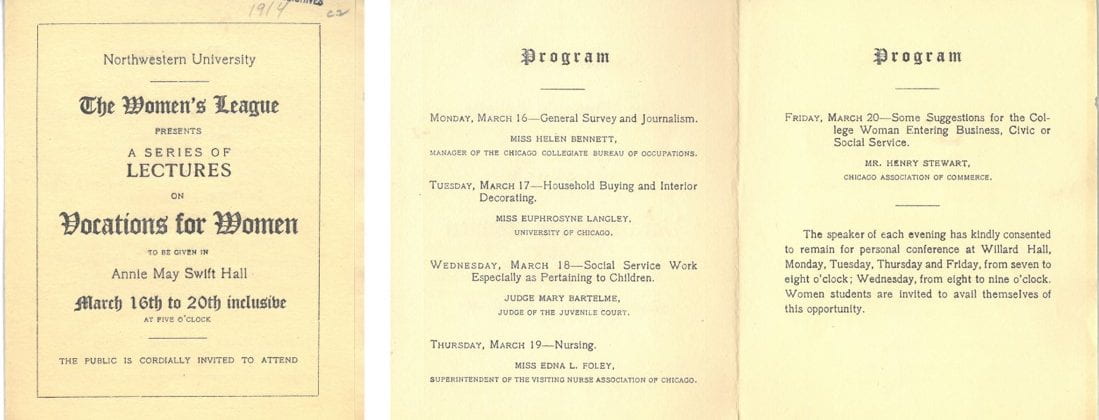

1906: The Woman’s League of Northwestern

The Woman’s League (later Women’s League) was formed to promote “fellowship among the women students of the university; to increase their sense of responsibility to one another; to establish friendly relations between the women students and the faculty women; and to be a medium by which the standards of the university may be made and kept high.” A later description noted that “much of the work of the Woman’s League has to do with rules governing dormitory and social life”—and fines could be levied for breaking the League’s rules.

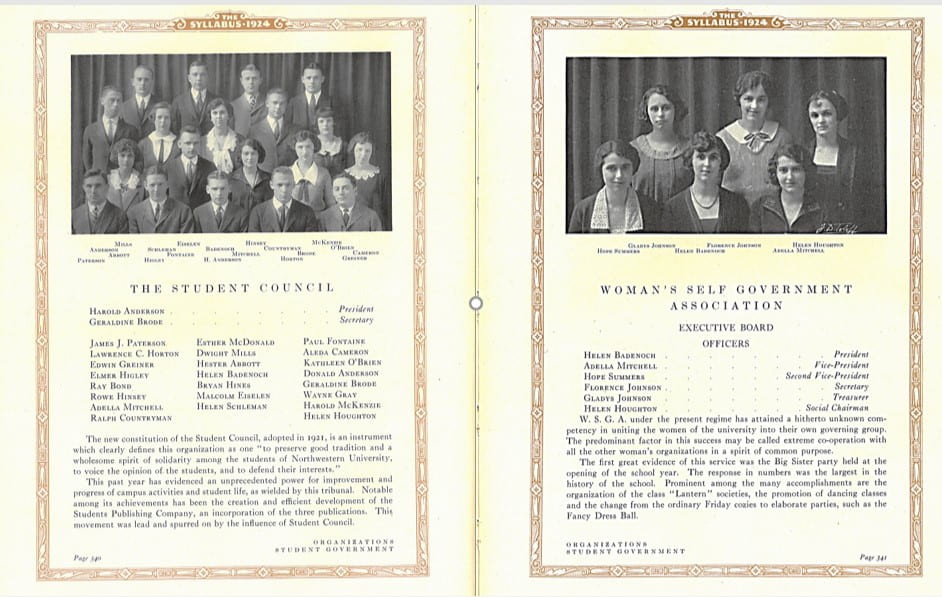

Student Council

By the mid-1910s, Northwestern students had established a campus-wide Student Council to give men and women students some autonomy and policy-setting authority over their extra-curricular activities. Women were eligible to serve as members and to hold office as Vice President or Secretary, but the women students maintained their parallel governance organization for another 60 years.

1922: Women’s Self-Government Association (WSGA)

In 1922 the Women’s League changed its name to match a title adopted by a number of other schools. Membership became automatic for entering women students, and the emphasis was distinctly on rules governing dormitory and social life.

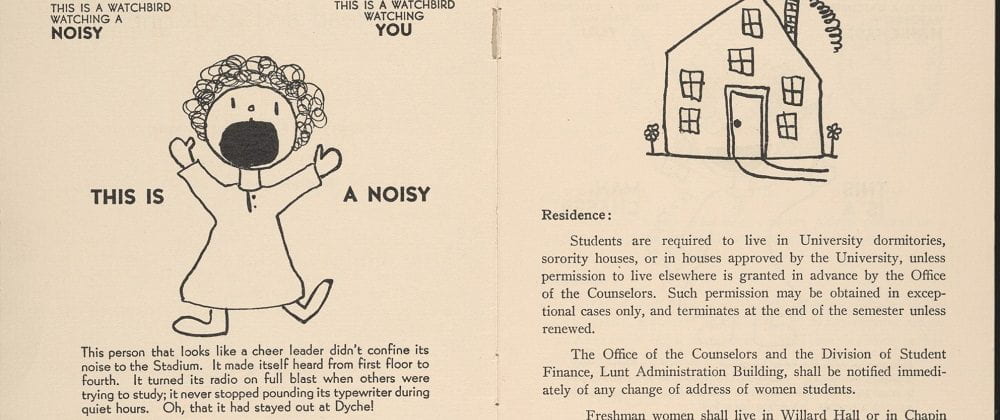

1939: “Read & Be Right”

In 1939, the WSGA began publishing an annual handbook for women students. To the accompaniment of cartoonish illustrations, the handbooks listed the rules for all women’s residences, including sororities—from dress (no Bermuda shorts at breakfast), to etiquette and propriety (especially where men were concerned), to getting permission to leave campus, to the complex system of hours. It also outlined the demerit system for broken rules, which would result in restrictions on hours—essentially, grounding. Further, the handbook suggests that women’s behavior was under scrutiny by “watchbirds” (RAs or housemothers, perhaps)—a much different approach from Dean Willard’s honor-system back in the 1870s. A new edition of “Read & Be Right” was published for the next 20 years.

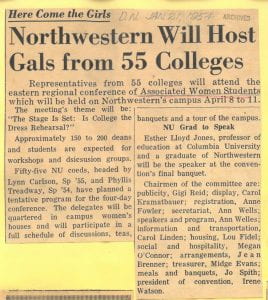

1950: Associated Women Students (AWS)

The self-government organization changed its name again in 1950. The new Associated Women Students (AWS) organized social and vocational events, now with a focus on the indoctrination of freshman women during new student week. It continued to publish Read & Be Right (with updated illustrations) until 1959. A Big Sister/Little Sister program matched incoming women with a seasoned student mentor to ensure that new students would adhere to the rules.

1969: The end of self-governance

In many ways, the self-governance model that women imposed on themselves worked at cross-purposes to the concept of education on equal terms with men. Whatever the original reasons for establishing it, women’s self-governance reinforced the boundaries of a separate sphere. The rules women students set for themselves perpetuated stereotypes of how a woman should behave, and confirmed a double standard by not expecting men to follow the same rules. But things were about to change.

Above all, the issue of parietals (the rules dictating hours for visiting, being out of the dorm, etc.), was becoming controversial, for women and men alike. By the mid-1960s, women were questioning the double standard that allowed men more freedom while women still had strict curfews. Soon women’s hours were lengthened, first for juniors and seniors; then seniors got keys to their residences, so they didn’t risk being locked out or fined.

In October of 1969, AWS sponsored a “Women’s Week” to stress its new, more supportive and less judicial role, but in November the organization was finally eliminated and replaced by a Woman’s Committee on the new Associated Student Government (ASG). In 1970, Eva Jefferson became the first woman president (and the first black president) of the ASG.

This essay is based on the Deering Library exhibit “On the Same Terms: 150 Years of Women’s Education at Northwestern,” and the accompanying publication. All images and documents are drawn from the University Archives Collections. Images from the Daily Northwestern and the Syllabus yearbook are used courtesy of Students Publishing Company.

Fall, 2019, marked 150 years since women could enroll as Northwestern undergraduate students. The University continues to commemorate this milestone—and the women/womxn who have shaped Northwestern—through 2020. Visit the 150 years of women website (https://www.northwestern.edu/150-years-of-women/) to learn more and get involved.