On January 19, 1970, a new chapter began in Northwestern’s history: the opening of the new University Library building. Today and tomorrow we look at the history, from the need for a new library, to the construction of the building — and why it looks the way it does.

The Library Outgrows Deering

On July 26, 1950, in a grand ceremony, Roger McCormick placed the Northwestern Library’s 1,000,000th volume on a shelf in Deering Library. In 1932, at the age of 13, he had shelved the first book in the newly opened, gorgeously Gothic building. But by the time the millionth volume arrived, Deering—which had been intended to house 500,000 books—was obviously overcrowded.

Meanwhile, the way students used the library was also changing. As in most research libraries, Deering’s book stacks had always been closed, with books requested at the circulation desk and retrieved by library assistants. In 1951, the stacks were opened, changing the relationship between students and books, and presaging a national shift in academic libraries from the use of large, common reading rooms to individual or small-group study areas closer to the stacks. A copy center took the place of a former typing room; in 1960, a student lounge was installed in the corridor on the ground level of Deering—a project spearheaded by Student Government President Richard Gephardt—which included seating, telephones, typing tables, and ashtrays.

However, despite modifications, it was clear that a building constructed in 1932 to hold 500,000 books in closed stacks, serving a student population of 5,000, could not meet the needs of over 8,000 students. Expressing the feelings of most students and faculty, a Daily Northwestern article in 1960 described how Koch’s Gothic cathedral of learning had become “the Monster on the Knoll,” a “cavern of lost books, poor lighting, uncontrollable heating, and six indoor outhouses…Deering has the acoustics of prosperous boiler plant—and hundreds of students holding impromptu political debates, fraternity meetings, social exchanges, and pre-examination seminars…”

Fortunately, in 1961 a new library building was proposed as part of a massive building program that would push the entire campus in a new direction (literally). A new page was about to be turned in the history of the University Libraries.

Making Room for the Future

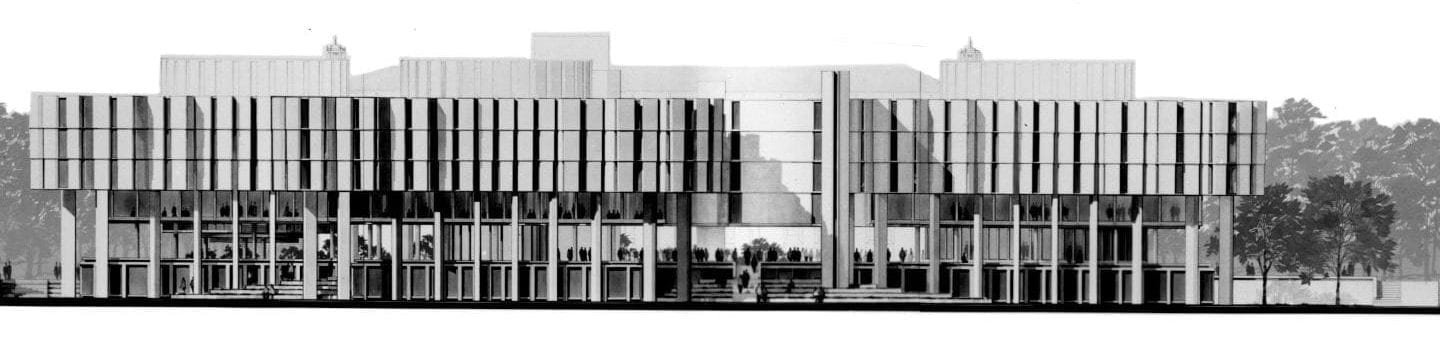

J. Roscoe Miller’s boldest move as Northwestern University President was the Lakefill Project, initiated in 1961, which entailed the purchase—from the state of Illinois—of 152 acres of land under Lake Michigan, allowing the University to expand eastward. As soon as plans were finalized, Miller appointed an eight-member committee to begin planning a new Library building that would occupy part of the 74-acre Lakefill Campus. The Faculty Planning and Building Committee was chaired by history professor Clarence Ver Steeg, working closely with architect Walter Netsch, of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (the firm responsible for the design of the Lakefill itself). In 1964, the Board of Trustees approved the committee’s plans; groundbreaking took place in 1966, and the new library was completed in December 1969. Construction costs came to $12,321,906, with 330,000 square feet of assignable space—enough room for 1.7 million volumes and 2,900 people.

The Library of the Future

Ver Steeg and Netsch put as much vision, theory, and passion into the new library’s planning as librarian T.W. Koch and architect James Gamble Rogers had invested in Deering. The resulting building was as different as it could be from Rogers’ and Koch’s structure. Deering Library, with its signature Collegiate Gothic style, had represented the age of closed stacks and central reading rooms, a library tradition that harked back to monastic libraries. The new library would look forward, not back, reflecting the futuristic aesthetic of its era, as well as advances in technology, and an updated interpretation of library use. As an Northwestern press release from 1969 summarized it,

“The New Northwestern University Library breaks with tradition because it was planned in a non-traditional way. Faculty and students in every department and school of the university were interviewed in-depth by members of the…Committee [in order to define] needs, goals, concepts, and academic principles. The New Library was conceived, not as a structure, but a living, growing, developing intellectual program to enrich and transform the quality of life for the entire academic community at Northwestern. In this sense, it embodies not only what the university presently is but what it aspires to become.”

The Future Embodied

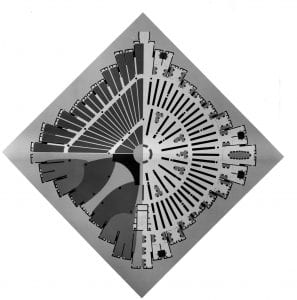

The new Library was indeed non-traditional, inside and out. Netsch was well known for his strikingly modern, “brutalist” designs (so named because the construction material was “béton brut,” the French term for raw or unfinished concrete). His plans for the new library called for three five-story, circular towers linked to each other on the first floor, standing on a broad plaza. Within the building, innovative features of the new library included:

- A “Core Library” consisting of about 50,000 non-circulating books, chosen by faculty and librarians, and aimed at undergraduates, representing “the distillation of the best of human knowledge” across many disciplines.

- Three circular “research pavilions” (towers), each one dedicated to books in one specific field of the liberal arts: history; social sciences; and humanities.

- Radial rather than linear palcement of book stacks, “spreading like sunbursts” from a central point on each floor of the towers, ensuring easy access to books and maintaining a non-intimidating “human scale in an intellectual environment.”

- A preponderance of individual study carrels, replacing outmoded group reading rooms by nestling students in the stacks among the books they needed

- “A unity of intellectual and social life” on the second floor of the Library, with the poetry collection adjacent to the listening and film facilities; the Forum Room as a “distinctive setting” for cultural programming; and the commodious (and separate) student and faculty lounges for relaxation.

- A spacious Plaza that invited the “community of scholars” to gather for outdoor events

- Plans to “accommodate to the rapid development of new technology…if the form of the research material changes dramatically to magnetic tapes or to information retrieval. …Space for a computer is presently set aside on the first level.”

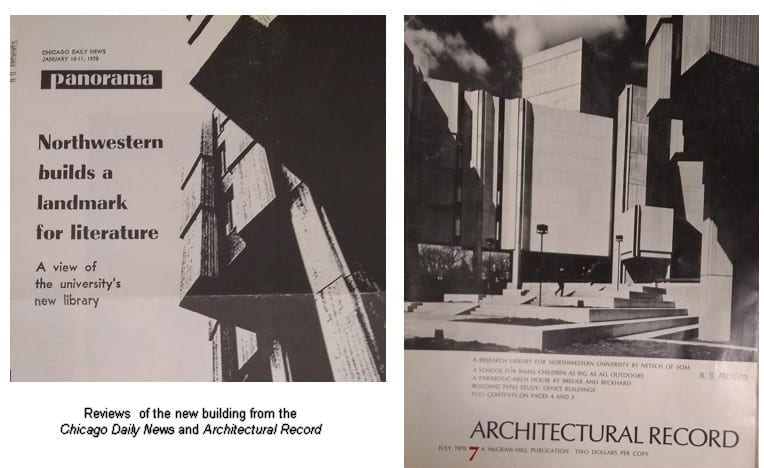

Northwestern’s modernistic University Library, and the rules-breaking concepts behind it, were discussed exhaustively in reports and press releases during the new library’s construction, and by reviews and articles in newspapers and architectural and library journals after it opened. Fifty Years into the Future

Fifty Years into the Future

Ver Steeg and Netsch were confident that the pavilions could easily be adapted, “should the future produce study demands not presently anticipated.” But they could never have imagined the scope of the digital revolution, with massive mainframes evolving into myriad forms of hardware and software to deliver and produce information.

Nor could they have guessed how interdisciplinary programs would challenge the theory of field-specific towers. And they could not have imagined that, in a twist of academic fate, 21st century students would once again seek out group study spaces, rather than work in the monk-like isolation of the radial stacks. After 50 years of use, still bravely adapting to changes in so many aspects of library use, Netsch and Ver Steeg’s “Library of the Future” continues to serve its publics (its fervent lovers and equally fervent haters alike)–with aplomb (and without sinking).

All images and sources for this blog come from The McCormick Library of Special Collections and University Archives. Daily Northwestern article reprinted courtesy of Students Publishing Co.