By Kevin Leonard, University Archivist

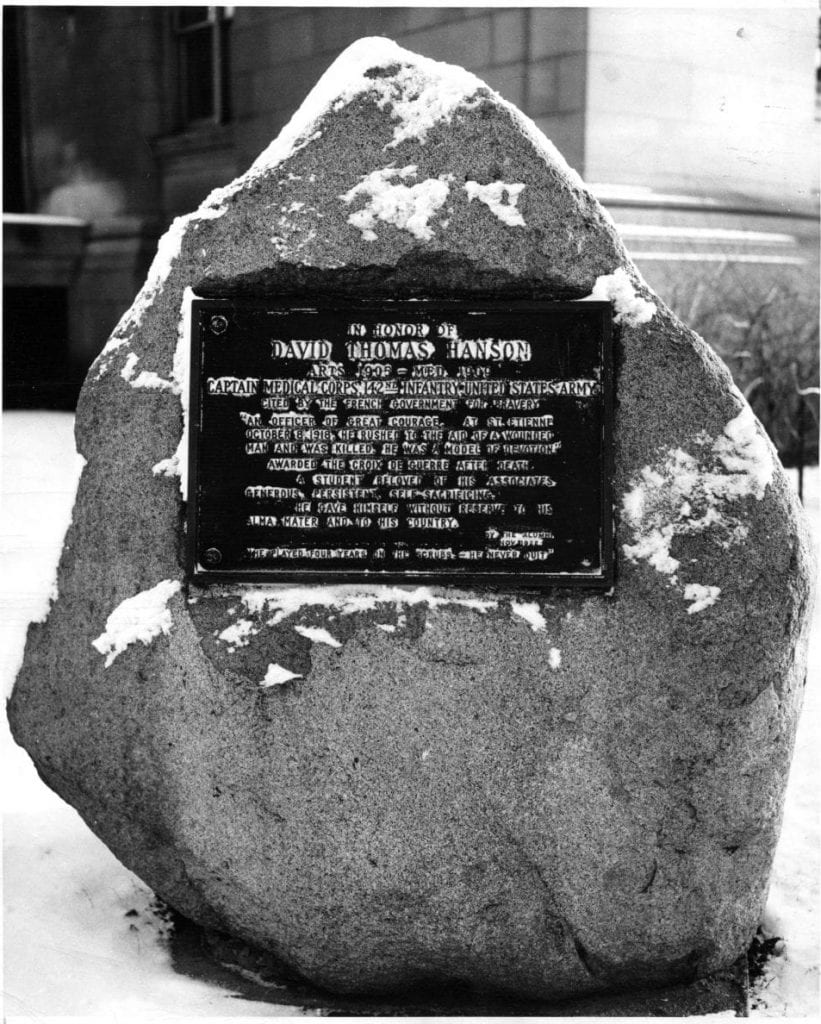

Partially screened behind a hedge southwest of Harris Hall, unseen and unnoticed by most, a monument stands to a Northwestern alumnus who gave his life a century ago, during the closing days of World War I.

Dedicated with much ceremony and noted by newspapers and magazines from throughout the United States, the monument – a bronze plaque set into a granite boulder – originally stood between Harris and University Hall but was moved to its present location as a precaution against the incidental damage that occasionally occurred when students gathered for the ritual painting of an adjacent and similar looking campus landmark, the celebrated Northwestern Rock.

Marking the life and sacrifice of David Thomas Hanson, the language of the memorial’s plaque is terse and direct:

In Honor of

DAVID THOMAS HANSON

Arts 1905 – Med. 1909

Captain Medical Corps, 142nd Infantry, United States Army

Cited by the French Government for bravery

“An officer of great courage. At St. Etienne,

October 8, 1918, he rushed to the aid of a wounded

man and was killed. He was a model of devotion.”

Awarded the Croix de Guerre after death.

A student beloved of his associates,

generous, persistent, self-sacrificing.

He gave himself without reserve to his

alma mater and to his country.

By the Alumni

Nov 1922

“He played four years on the scrubs. – He never quit.”

Born August 27, 1877, at Tuscola, Illinois, Hanson grew up on a farm, the son of a middle-aged, German-born father, Henry Hanson, and his young, Kentucky-born wife, Ann. Hanson attended local schools and eventually made his way to Evanston at the close of the 19th century, attending the Northwestern University Academy, the secondary school once operated by the University, and then enrolling in the College of Liberal Arts. Hanson’s association with Northwestern was interrupted when he followed the call to military duty at the time of the Spanish-American War. The short duration of that conflict precluded campaigning in Cuba but Hanson served for nearly two years with Company C of the 45th United States Volunteer Infantry Regiment during the subsequent Philippine-American War.

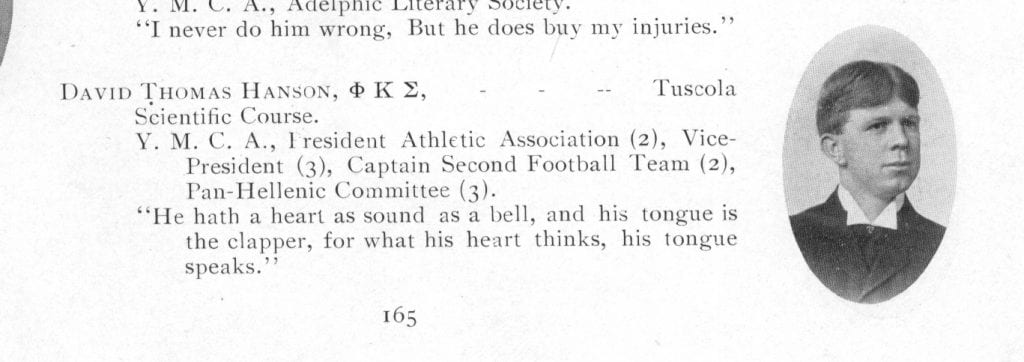

He returned to Evanston in 1901, ultimately taking his bachelor’s degree from Northwestern in 1905, while working odd jobs to finance his college expenses. Hanson was a gregarious student, involving himself in the activities of the local YMCA, the student athletic association, and the Phi Kappa Sigma fraternity. Notably, he also played football, but never with the proficiency to crack Northwestern’s starting eleven. Hanson spent four years participating in drills and practices, taking his lumps and helping to hone the abilities of teammates, but remained sidelined during games, forever unheralded.

Hanson next pursued his longstanding interest in medicine, enrolling at Northwestern’s Medical School and taking his M.D. degree in 1908 (though the memorial plaque gives an erroneous date of 1909). He thereafter followed the migratory path of a younger brother, settling in the Texas panhandle and establishing his general medical practice in Amarillo. With violence flaring on the U.S.-Mexican border, Hanson was mustered into federal military service in May, 1916, as a first lieutenant in the Medical Corps of an Amarillo unit of the Texas National Guard. He spent several months in the border region before mustering out of service March 26, 1917.

Five days later, in anticipation of U.S. entry into World War I, Hanson again entered into military life and received a quick promotion to captain’s rank. He took his billet with the Medical Corps, 142nd Infantry Regiment of the Texas National Guard, federalized into the U.S. Army’s 36th Infantry Division. Hanson and the 36th reached France in July, 1918, and received orders to move to the battlefront in late September. His inexperienced regiment was put into line near St. Etienne in early October, in time for heavy involvement in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, the final large battle of the war and the deadliest single battle in American military history.

Eschewing advice to disguise his rank as an officer, Hanson believed that the Red Cross brassard he wore on his arm would suffice to spare his deliberate targeting by enemy snipers. When his unit received orders to begin its assault on German lines, taking fire immediately, Hanson moved out with the troops, rendering assistance to the fallen and establishing a medical aid station. He left the relative safety of his station and was killed, while aiding a wounded soldier, taking a bullet to the head.

In the exigencies of battle, Hanson’s body initially was interred close to where he had died. Disinterred after the war, Hanson’s remains ultimately were repatriated to the United States and reburied in his hometown of Tuscola. His service and sacrifice were recognized by the French, with a posthumous award of the Croix de Guerre. In his adopted state of Texas, between July and September, 1919, the newly founded American Legion organized and chartered in Amarillo its Hanson Post 54, which remains to this day.

Hanson was one of over 60 known members of the Northwestern community, mainly alumni and students, to have died in World War I. Their names are inscribed on plaques now found inside Alice Millar Chapel as well as on a large boulder situated at the north end of campus. Hanson is the sole individual from that war to be recognized with his own monument. Why is that? Certainly his sacrifice and gallantry are worthy of appreciation and his patriotism, serving in three separate conflicts over nearly a 20 year span, was remarkable.

But the nature of Hanson’s accomplishments as a student or, rather, his lack of signal distinctions as a student were, in fact, what made him an attractive candidate for special remembrance. Recall, for example, his participation in football: he was for four years a “scrub.” That is, Hanson, while he participated, was anything but exceptional as an athlete. And Northwestern’s president, at the time of the monument’s dedication, made a point of publicly stating that Hanson was completely unexceptional as a student. So, in the classroom and on the football field, Hanson was, at best, the personification of the average; someone one likely would hardly notice. And that averageness was the reason, among Northwestern’s war dead, that he was singled out for exceptional recognition. It was because Hanson, though remarkable in his sacrifice, demonstrated qualities of loyalty and devotion and service that other average people might themselves aspire to possess. His were qualities of personality and fortitude, traits and habits that all of us might learn, not ones reliant on exceptional physical and intellectual gifts. Hanson was held up as an exemplar of the typical, of what an unexceptional person might do when guided by civic-minded ideals. As The Chicago Tribune editorialized, “The brief record of David Hanson is an idealization of the average citizen….Genius must guide a nation at times, but Hanson was the material without which neither a great nation nor a sound society can exist.”

Hanson’s Northwestern monument was dedicated November 23, 1922, in a ceremony before more than a thousand students, alumni, and dignitaries. The early 1920s, under the leadership of NU President Walter Dill Scott, marked the beginning of a dramatic period of prosperity and a resulting, major expansion of the University’s physical plant. Significant construction projects, including Northwestern’s entire Chicago Campus and its south campus sorority house and dormitory quadrangles, were realized largely before the end of the decade. And, in addition to the Hanson monument, Northwestern also created another war memorial: its Avenue of Elms. Dedicated on Memorial Day, 1923, the Avenue was a formal arrangement of 75 elm trees, each dedicated to a Northwestern alumnus or student who lost his or her life in military service during the Civil War and World War I. (Three females were so recognized.) Looking beyond Evanston, at the national context for monuments, the nation’s first Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, at Arlington National Cemetery, was dedicated on Armistice Day, November 11, 1921. The Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., dates to May, 1922.

But the early 1920s were known as well for tension and unease. Northwestern students of the time had become different from their campus forebears and were increasingly participating in the social, cultural, and behavioral excesses of the Roaring Twenties. Locally, Northwestern student Leighton Mount had disappeared in a 1921 hazing incident that turned dangerous, costing him his life. More ominously, the Wall Street Bombing of September 16, 1920 killed 38 and wounded hundreds while the murder trials of anarchists Sacco and Vanzetti in Massachusetts were drawing increasing attention and concern. In Tulsa, a 1921 race riot convulsed the city and resulted in hundreds of deaths and injuries. The Teapot Dome scandal associated with the Harding administration was under investigation and had become public knowledge by 1922. So, perhaps in November, 1922, it was getting well past the time to recognize civic virtue and noble service. And David Hanson, with Northwestern drawing emphasis to the ordinary aspects of his character, became – after his death a century ago – an emblem and an ideal of what we all might be through selfless devotion to duty.