Blog by Joshua Dean, NU ’23.

Under Article 25 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, it states, “Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services, and the right to security in the event of unemployment, sickness, disability, widowhood, old age or other lack of livelihood in circumstances beyond his control.” The United Nation’s list of fundamental rights ensures that people have their basic needs met, have equal opportunities, and have protection from abuse, especially for those part of vulnerable groups. However, if unchecked, the United States will violate this basic human right. As the reaches of COVID-19 have stretched to every corner of the economy, many people have lost their jobs and income. As a result, there is an eviction crisis in the United States that has never been so apparent. While COVID-19 by no means started an affordable housing crisis in the United States, it clearly exacerbated the existing crisis to the point where it is today.

Many Americans were already living paycheck to paycheck before the COVID pandemic. As a general rule, it is recommended not to spend more than 30 percent of one’s income on housing, for there are other expenses like child care, medical, food, transportation, savings, and taxes, just to name a few. Before 2020, almost half (47.5%) of all renter households were spending more than 30 percent of their total income on rent, and roughly 1 out of every 4 American renters were paying more than half of their income towards their rent. The grim financial reality of many Americans turns more staggering below the poverty line. In 2018, for instance, the majority of renters under the poverty line were paying at least 50% of their income on rent, and one in four renters were paying 70% of their monthly income on rent. Thus, it is evident that the pandemic hit amid a pre-existing and intense public issue that already needed to be addressed.

The federal government has taken some steps to address this issue. The CARES Act was passed in late March, partly to mitigate the possible insurgence of the rise in eviction rates, among many other effects caused by COVID-19. However, across the United States, many of these temporary protections and benefits expired at the end of July, including unemployment benefits and moratoriums that prevented landlords from evicting tenants, which already only protected less than one-third of the renters in the United States.

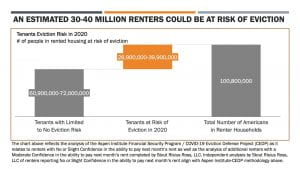

The wealth gap is also further widening as a result of the eviction crisis, as Americans are unable to find work, despite the fact that many are more than willing to work. According to the Urban Institute, low-income renters are more likely to have jobs lost due to the COVID pandemic, especially in sectors like the food services and retail industries. Because of the loss of jobs and the loss of many of the federal, state, and local protections, the US Census estimates that 28 to 39 million people in 17 million households may face eviction within the next several months.

Click image for larger view.

According to the National Multifamily Housing Council, roughly 1 out of 5 renters were unable to make their payment on time in July. August may end up being much worse. According to the US Census data, almost 1 out of 3 renters have slight confidence or no confidence that they will be able to make their rent payment in August on time. The economic downturn and the risk of eviction, which can result from as few as one or two missed payments, could escalate and sweep across the United States with devastating effects very quickly.

There are several consequences of eviction. Eviction is closely tied with many health problems ranging from increased risk of teen pregnancy, early drug use, anxiety, depression, and others. Evictions also negatively impact respiratory conditions, which could be detrimental and potentially increase the severity of COVID-19. Eviction also leads to greater difficulty in applying for credit, borrowing money, purchasing a home, and therefore can lead to declines in neighborhood quality, safe housing, and further job loss. According to the Urban Institute, housing instability in particular negatively affects child development, greatly impacting their developmental well-being and education for years afterwards. A study by the University of Granada concluded that 95.1% of respondents experiencing home eviction felt fear, helplessness or horror during the eviction process, and 72.5% of this subgroup could be categorized as having PTSD, according to the symptoms outlined in the DSM-IV, the official manual of the American Psychiatric Association.

The COVID pandemic could very quickly turn from a health crisis into a long-term and unprecedented homelessness crisis. States are projected to be impacted disproportionately by the eviction crisis.

For instance, as shown in the infographic, 59% of renters in West Virginia are at risk of eviction, compared to 22% in Vermont. As emergency funds are designed to cover 3 to 6 months’ worth of living expenses, many Americans’ emergency funds are about to dry up, if they have not already.

Comparable to many other inequalities that have been illustrated and further widened since the COVID pandemic, COVID-19 has also exacerbated the inequality of the housing market. Communities of color are disproportionately impacted by evictions, as Black and Latino households are twice as likely to be renters than white households.

In addition to the impact of the COVID pandemic on tenants, the COVID-19 housing crisis will also significantly negatively impact small property owners and communities at large, as small property owners are at greater risk of foreclosure and bankruptcy than large property owners and the common practice of gentrification, respectively.

Every person deserves stable housing. As referenced earlier, the United Nations’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights considers secure housing to be a fundamental human right, especially considering the multitude of long-term effects it has on a person’s overall well-being as discussed. While the federal government has implemented the CARES Act, there should be a more comprehensive effort to address this public issue, through an extension of moratoriums and emergency rental assistance especially. Further policy interventions should be put in place to ensure that the U.S. adheres to this fundamental human right, as to avoid suffering, to save lives, and to prevent further harm along the process.

Joshua Dean is a member of the Class of 2023, majoring in biomedical engineering. He joined GlobeMed at the beginning of his freshman year, and he looks forward to continuing his active involvement in the next three years.