Blog by Joshua Dean, NU ’23

The Constitution of the World Health Organization (WHO), one of the most reputable international health organizations, since 1948, defines health as “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity” (Institute for Global Citizenship (IGC), 2013; World Health Organization, 2020). This longterm association of mental health to overall well-being illustrates the importance that people perceive mental health to have, evidenced by this statement made more than 70 years ago. Given that WHO includes mental health as part of the definition of health, any abnormal deviations from a positive mental health state should be considered an important problem that needs to be addressed on a local, national, and global level. Despite this, mental health is widely perceived differently from physical health, ranging from negative societal perceptions to discrimination in coverage. A large factor that determines this differentiation is social stigma, resulting from a fundamental lack of understanding. This is no different in Uganda.

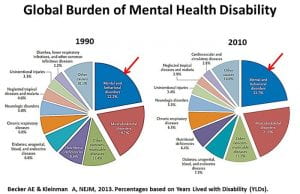

Whether residing in high-income countries or in low and middle-income countries (LMIC), the widest-reaching global burden faced in all communities is mental and behavioral disorders, surpassing the likes of musculoskeletal disorders, nutritional deficiencies, diabetes, and chronic respiratory diseases as illustrated in Figure 1 (Price & Boonmak, 2016).

Figure 1 (click image for larger view)

Global Burden of Disabilities

Although there are people who are at higher risk of developing a mental health or behavioral disorder, every person is prone to developing a mental or behavioral disorder, no matter their background. In addition, just like any disorder, a person can have more than one; more than 26 million people worldwide are diagnosed with several mental illnesses at one time (Wainberg et al., 2017). Figure 1 also shows that it is truly a global issue, as it has not decreased in magnitude from 1990 to 2010. In response to this issue, mental health, as a global problem, has only recently started to be addressed on a global scale.

Regarding the differential effect on various groups, there are demographics that are at higher risk at developing a mental or behavioral disorder. These groups include, but are not limited to, members of households living in poverty, victims of violence and abuse, older people, minority groups, people with chronic health conditions, the LGBTQ community, and women. Possible reasons that may sort these groups at higher risk of developing a mental health condition could involve having greater loads of stress, feelings of exclusion, the inability to connect and to create an outlet, a lack of available treatments and resources, or a genetic predisposition to the condition (Wainberg et al., 2017).

Moreover, there are wide disparities regarding mental health treatments when comparing high-income countries to LMIC. Nearly 28% of countries do not have a separate budget for mental health. However, of the countries that do have a separate budget, an astounding 37% of these countries spend less than 1% of their healthcare budget on mental health, Uganda included with less than 1% of the 9.8% of its GDP allocated to healthcare (World Health Organization, 2003). On the other hand, compare Uganda’s proportional investment to the UK’s 10% investment into mental healthcare (Molodynski, Cusack, & Nixon, 2017). Among many other compounding factors, such a disparity in investment priorities contributes to the differences in available treatment between high-income countries and LMIC.

87% of the population in Uganda lives in rural areas and here are 28 inpatient psychiatric units throughout Uganda – and only one mental hospital. Over 60% of these beds are in close proximity to Kampala, the capital of Uganda. Thus, those living in much of the country have little access to mental healthcare (Shah et al., 2017). The majority of the national mental health funding is directed to that national mental hospital, called Butabika Hospital. Established in 1955, Butabika hospital now has 500 beds, with frequent overcrowding, and has approximately 430 staff. Despite Butabika Hospital being the only nationally funded mental hospital, many severe criticisms have surfaced in the last couple of years. Butabika Hospital detains without assessment, houses patients in seclusion rooms without toilets, fails to distinguish between compulsory and voluntary admissions, offers no separate facilities for children, and relies heavily on pharmacological treatment, which often results in heavy side-effects. Ugandan legislation is also highly out-dated and stigmatized; the current active legislation regarding mental health treatment dates back to 1964. While there is a current draft of a new mental health bill, its introduction has been repeatedly moved back, and so discriminatory practices in Uganda still continue extensively (Molodynski, Cusack, & Nixon, 2017).

The current lack of public funding to the mental health sector greatly contributes to the mental health crisis in Uganda. Skilled healthcare workers are leaving Uganda for higher wages in high-income countries, such that there is not enough trained medical staff. The lack of trained medical staff also means that communities also lack prescribable medications. In Uganda, there is also an absence of publicly funded programs that aid individuals or their families for any mental health coverage, so families must bear the economic burden of taking care of the mentally ill. With much of the family’s time preoccupied, this can also cause significant social costs. While seeking evidence-based medical treatment is common in the United States, it is uncommon to do so in Uganda. If, in the rare instance that families do seek medical treatment, it can be very costly. In the past and even today, it is a common notion to regard “mentally disturbed people as incurable sub-humans” or a “lost cause,” further contributing to the barriers to evidence-based treatment and the low national budget to mental health (World Health Organization, 2003).

The misallocation of resources keeps the underprivileged in chains, as it is very difficult to find a means to treat the underlying issues. Mental illnesses can lead to further mental decline, economic instability, and social decline. Employers are less likely to hire people with a mental health disorder, trapping people in poverty. This potential inter-generational poverty cycle particularly impacts a large number of people in Uganda. The estimated incidence of mental illnesses is massive: 35% of Ugandans suffer from a mental illness, and 15% of Ugandans require treatment. It is likely that the incidence of mental illnesses and the need for treatment is much higher (Molodynski, Cusack, & Nixon, 2017). The number of people affected by mental health disorders greatly varies from source to source as well, as there is little pre-existing research on mental health in Uganda. For instance, in a survey of 387 respondents in Jinja and Iganga districts, Eastern Uganda, contrary to the estimate by WHO, found that 60.2% of people had a diagnosable mental illness. In addition, most disorders were classified as moderate or severe (72.8%), by international standards (Abbo, Ekblad, Waako, Okello, & Musisi 2009). Moreover, the World Health Organization estimates that 90% of those with a mental health disorder never seek treatment (Molodynski, Cusack, & Nixon, 2017).

Even though many people experience mental health issues because of systemic and societal reasons that are interwoven with many other social problems, misconceptions largely inhibit people from seeking treatment. Many Ugandans believe spirits and witchcraft to be the cause of mental illness, so they will commonly seek traditional healers before, if ever, seeking evidence-based medical help. While traditional healers are generally patient-centered and caring, their practice is not based on science and often applies harmful practices, including chaining and tying the patients down for long periods of time to ‘ward off’ the spirits. It has been reported that 80% of the patients in mental hospitals sought traditional healers before seeking medical help, delaying evidence-based treatment and most likely offsetting the best chances of full recovery (Molodynski, Cusack, & Nixon, 2017).

With the emigration of medically trained personnel, the workforce required to treat the ongoing mental health crisis in Uganda is dwindling. Uganda joins 45% of the world’s population that lives in a country with less than one psychiatrist per 100,000 people, at a rate of 0.08 psychiatrists per 100,000 people. Furthermore, only 1.13 per 100,000 people work in mental health facilities or private practices (Kigozi, 2010). With a lack of staff and personnel, it is no wonder why mental health problems still persist in Uganda. In addition, most psychiatrists are in urban areas, further decreasing the mental health treatment options for rural communities. Therefore, transportation is a major issue, making psychiatrists even more inaccessible.

While the government has taken a minimal role in defining or mitigating the mental health crisis, there are several public education and awareness campaigns, and social movements run by grassroots organizations that try to address the mental health crisis. Specifically, these efforts hope to especially reframe the perspective on mental health, notably by diminishing negative stereotypes and stigmas. For instance, the Adonai Centre, a Ugandan non-profit organization that is partnered with Northwestern’s GlobeMed branch, runs check-ins with local families to check in with their mental health. More broadly, the National Mental Hospital provides mental health support. There is also international aid from corporations and high-income governments. For instance, programs such as Emerging Mental Health Systems (EMERALD) and the Programme for Improving Mental Health Care (PRIME) both aim to create sustainable mental health treatments in LMICs, including Uganda (Shah et al., 2017). In addition, Basic Needs aids in the effort of ending the cycle of poverty from mental illnesses by helping individuals set up businesses and access professional training (Molodynski, Cusack, & Nixon, 2017). Another example of a grassroots organization is the Tumaini Foundation, run by Liz Kakooza, who hopes to raise awareness of mental health and to create safe spaces for people to talk (Whiting, 2019).

Figure 2 (click image for larger view)

Comparative Government Expenditure on Mental Health Per Capita Worldwide

While government expenditures have been discussed previously, Figure 2 physically depicts by geographical region the comparisons of such expenditures on mental health per capita in 2017. Social media has also notably been one of the most active ways to spread awareness of mental health. Especially considering the current environment caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, much of the information and communication that is circulating is through the means of Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

Coronavirus has only exacerbated the intensity of the social problem of mental health. Regarding individuals with pre-existing or underlying psychiatric conditions, the environmental changes and effects of the coronavirus can significantly increase symptoms for many of these people. Thus, proper monitoring and evaluation of psychosocial needs is very important! Social isolation, lessened travel, being away from loved ones, financial insecurity, misinformation, and curfew all propagate these issues. However, as of August 12, it is still necessary to keep the already 1,332 total confirmed cases of coronavirus in Uganda as low as possible (Ministry of Health, 2020). Coronavirus will surely have long lasting impacts on the future of the mental health social problem in Uganda.

While there are many barriers to better treatment options and availability for the mental healthcare system in Uganda, there is much hope in addressing these issues in an effective manner. Due to the varying complexities and cultural differences within Uganda, there should be a community-focused mental health treatment and awareness program established that links closely with functional recovery through work and family networks. Pharmaceutical companies should also increase drug availability in Uganda (as well as other developing countries). GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), a pharmaceutical company, has stated that it will no longer be pursuing patents in developing countries (Molodynski, Cusack, & Nixon, 2017). Other pharmaceutical companies should follow GSK’s lead on this matter. Furthering the education of community members and community health workers would also be integral in stopping the spread of misinformation. Such a formal and informal set of integrated community mental health services would be critical for ensuring that there is proper support, monitoring, and care plans in place to help the general population as well as those with underlying or pre-existing conditions. With the implementation of many of these changes having already started, the future of the mental health social problem in Uganda will indeed be a difficult problem to address, but many strides are still being made and the future is looking to be a positive one.

Joshua Dean is a member of the class of 2023. He is majoring in biomedical engineering. He joined GlobeMed at the beginning of his freshman year and is excited to continue his involvement.

Sources:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2890991/

https://ijmhs.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1752-4458-4-1#citeas

https://publichealth.wustl.edu/mental-health-global-health/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5663025/

https://www.macalester.edu/news/2013/10/why-global-health-matters/

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1178632917694350

https://phcfm.org/index.php/phcfm/article/view/1404/2279

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5553319/

https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/08/uganda-mental-health-stigma-depression-healthcare-africa/

https://www.who.int/mental_health/policy/services/3_context_WEB_07.pdf?ua=1

https://www.who.int/about/who-we-are/frequently-asked-questions

It’s really badly off in uganda, people can only rely on NGOs, the government is putting limited effort

I would like to talk with the owner of this article. Thank you please reach me at my email. Or Facebook group call Grants for Global Change

Thank you Joshua for his insightful article. I came across it while researching for a proposal for funding for our mental health initiative, Reciprocity Initiative Uganda that is promoting access to mental health via online platforms and awareness through social media. Any organisations or persons willing to partner or sponsor our cause kindly reach us on reciprocityug@gmail.com